“We have now disproved the idea that we’re never, in this country, going to tax or charge a significant environmental harm.” That quote, uttered by me this morning to a writer for Earther magazine, is as good a lead-in as any to tell you about an historic victory in New York that I view as a big shot in the arm for carbon taxing.

See opening paragraph for link to the story in Earther magazine.

This past weekend, our state legislature approved a far-reaching, first-time-in-this-hemisphere plan to charge vehicles driven in the heart of a big city — mid and lower Manhattan in this instance — a congestion fee. While the bill punts key details to a new city-state panel, the contours are clear enough: driving a private car into the “congestion zone” south of 60th Street will cost as much as $12 during peak hours, with higher fees for trucks. When the plan starts up, in January 2021, traffic in the zone is expected to thin enough to raise travel speeds in the zone by 12-15%; that figure will rise as the estimated billion dollars a year in congestion revenues (paid by the remaining vehicles) are invested in modernizing the subways.

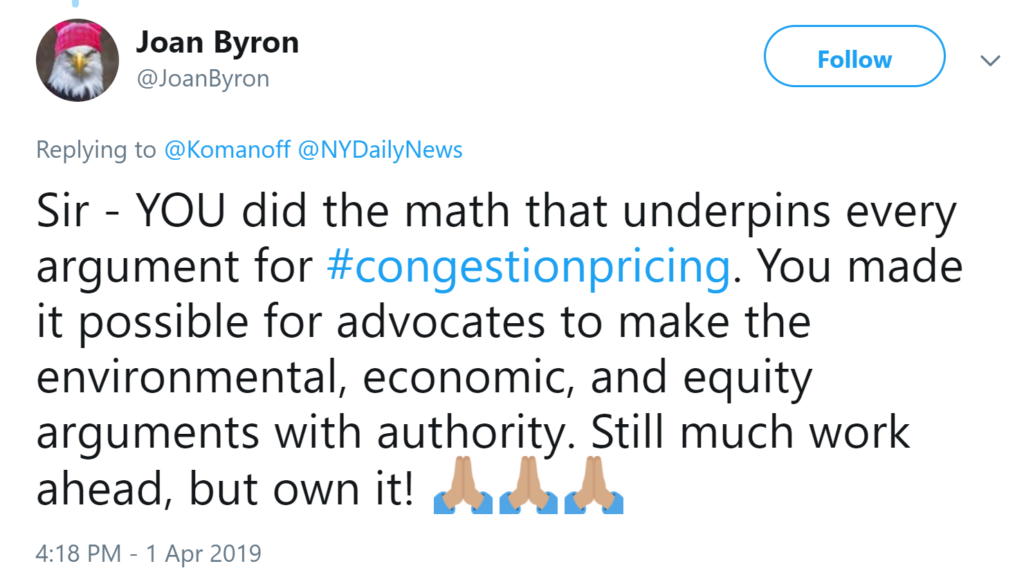

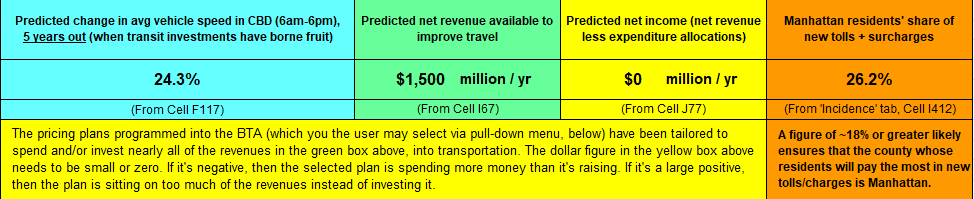

As most Carbon Tax Center followers and supporters know, I worked hard for this win. Over the past dozen years I spent 5,000 hours (!) creating and deploying a spreadsheet model that is kaleidoscopic enough to calculate the traffic and revenue and environmental benefits of any Manhattan pricing scheme, yet transparent and nimble enough to be used by other Excel jockeys — including the consultants that the governor’s office hired to scope out congestion pricing. I also wrote scores of posts for Streetsblog, the scrappy and admirable blog that is a nerve center for NYC’s “livable streets” community, each post aimed at steeling advocates on some aspect of congestion pricing math, policy and politics.

I say this not to tout my role. The forces that coalesced behind congestion pricing and made it unstoppable were immense, as they had to be to bring along the governor and legislature in the face of widespread cynicism, apathy, resentment and motor-worship. There were scores, then hundreds, then thousands of advocates pushing for this. That said, I believe that my years of calculations, both mathematical and political, lent gravitas to my thoughts on the meaning of this victory.

The huge mutual regard among NYC “livable streets” advocates helped push congestion pricing through the legislature.

New York’s enactment of congestion pricing is a big win for climate. Not in the sense of immediately reducing carbon emissions. By itself, the charging scheme will eliminate only around a million tons of CO2 a year (half by reducing vehicle use, and half by diminishing stop-and-go traffic). That’s a mere 1/5,000 of U.S. emissions. But it will make New York — and other U.S. cities, if they follow suit — more fair, civilized and prosperous. That will help shrink the country’s carbon footprint by fostering growth in “inherently green” (smaller-footprint) cities rather than sprawled-out suburbs and exurbs, as Jeff Blum and I pointed out last month in The Nation (and on this blog).

But an even bigger payoff lies, I believe, in establishing the precedent of finally taxing an environmental harm. With congestion pricing, the harm being taxed isn’t emissions, it’s traffic congestion (more technically, each vehicle’s “congestion causation” from abetting the slowing of traffic). The same principle — the most direct way to effectuate less of something is to price it at its true cost — animates carbon taxing.

Society is concluding at last that carbon emissions must be shrunk, rapidly and radically. That requires (i) intelligently regulating sources of emissions (building codes, efficiency standards), (ii) judiciously subsidizing evolving alternatives (wind, solar), (iii) researching and developing promising new low-carbon demand and supply technologies, and (iv) taxing fossil fuels so that their climate damage figures in their price.

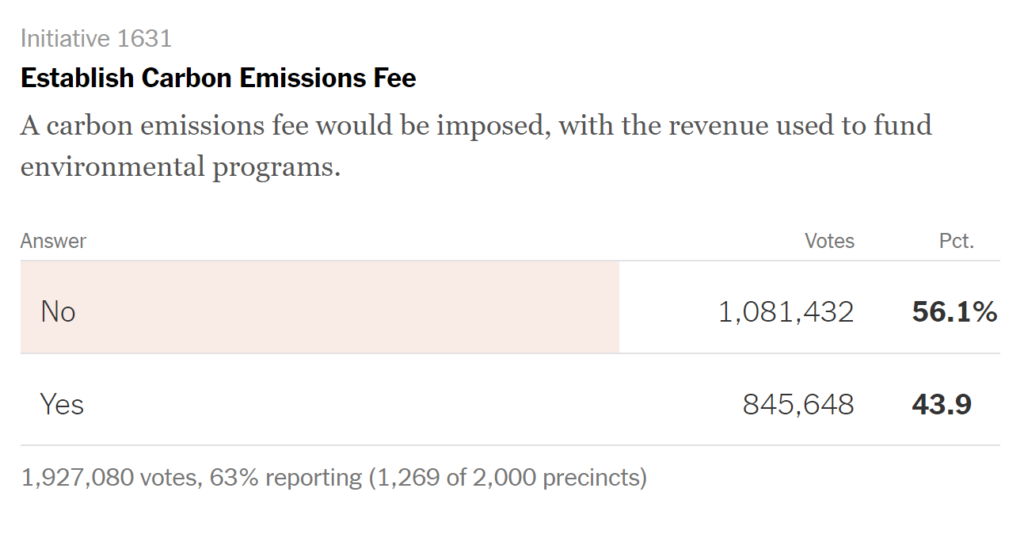

U.S. states and, at times, the national government haven’t done a bad job on the first three. But we’ve never done the last: taxing fossil fuels’ carbon content and emissions. Indeed, we’ve never explicitly taxed any large-scale environmental harm. And the double defeat of carbon tax initiatives in Washington state made it easy to lose hope that we ever would.

Now, the enactment in New York of a plan that frontally taxes a major societal harm — driving in a congested (and transit-rich) city center — has disproved the idea that substantially taxing an environmental harm is impossible in the U.S. We can put that particular bit of defeatism to rest.

To be sure, enacting a national carbon tax remains a far heavier lift than a single city or state passing congestion pricing. While regional factionalism — between Manhattan and the boroughs, between NYC and its suburbs — was a big hurdle, congestion pricing’s lesser scale allowed the transit benefits from the congestion revenues to take center stage in the advocacy campaign.

Indeed, subway relief paid for with congestion tolls emerged as a far more powerful organizing theme than congestion relief itself. So be it. The takeaway is to make a publicly guided, investment-based program — a Green New Deal — the rubric for tackling climate change and enacting a robust carbon tax as both a pay-for and a powerful change agent.

We’ll post more about that in the coming weeks. For now, it’s fair to say that carbon taxing for the U.S. has taken a major step forward. With enactment of congestion pricing for New York City, the road to a carbon tax and meaningful climate policy has definitely gotten clearer.

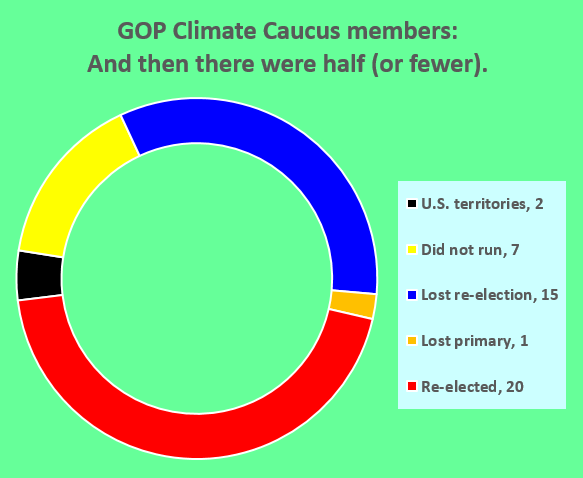

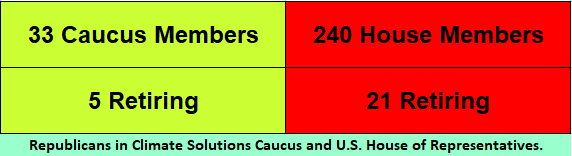

It is true that Republican caucus members on the whole were more vulnerable than other Republican incumbents, for two separate if complementary reasons. One, deep-red districts where climate concern is relatively low tend to be harder for Democrats to wrest from Republicans. Two, some Republicans whose electoral standing was shaky to begin with saw the caucus as a way to bolster their campaigns. For an effective price of zero, these members could signal their independence from Republican denialism and thus burnish their appeal to Democrats and so-called Independents.

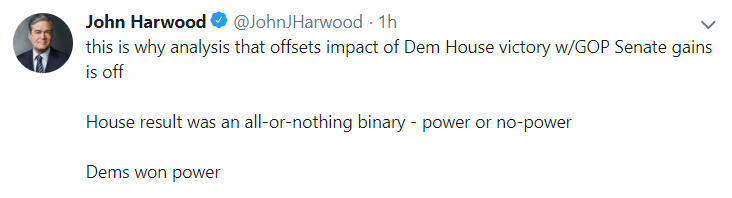

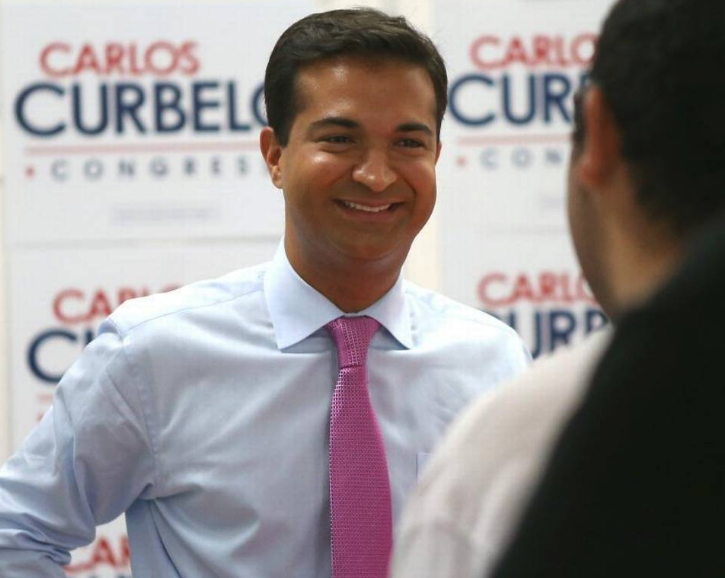

It is true that Republican caucus members on the whole were more vulnerable than other Republican incumbents, for two separate if complementary reasons. One, deep-red districts where climate concern is relatively low tend to be harder for Democrats to wrest from Republicans. Two, some Republicans whose electoral standing was shaky to begin with saw the caucus as a way to bolster their campaigns. For an effective price of zero, these members could signal their independence from Republican denialism and thus burnish their appeal to Democrats and so-called Independents. Shed a tear, then, for Carlos Curbelo, but only briefly. The Democratic takeover of the House is worth an eternity of Republican caucus members’ feints, signalings or even token bills. As CNN’s John Harwood

Shed a tear, then, for Carlos Curbelo, but only briefly. The Democratic takeover of the House is worth an eternity of Republican caucus members’ feints, signalings or even token bills. As CNN’s John Harwood

And revenue-neutrality isn’t the only flashpoint lurking in the CLC-ACD proposal. Another element of the deal — one that has won a measure of oil-industry support — would immunize fossil fuel companies against litigation seeking to hold them accountable for climate damage caused by their products. Earlier today, a leading strategist and backer of such litigation, Lee Wasserman of the Rockefeller Family Fund,

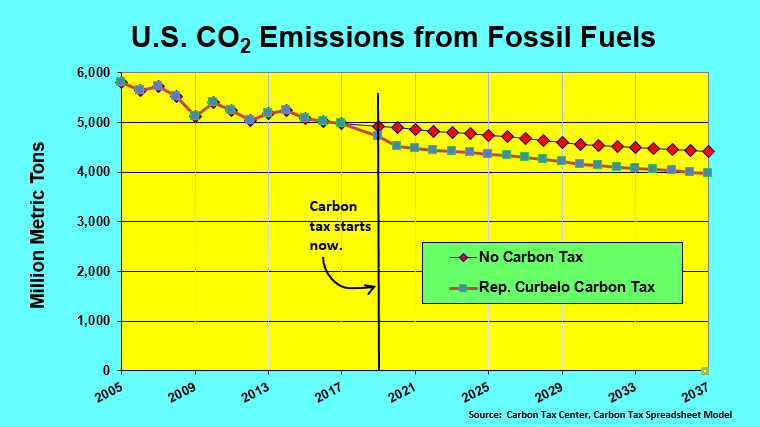

And revenue-neutrality isn’t the only flashpoint lurking in the CLC-ACD proposal. Another element of the deal — one that has won a measure of oil-industry support — would immunize fossil fuel companies against litigation seeking to hold them accountable for climate damage caused by their products. Earlier today, a leading strategist and backer of such litigation, Lee Wasserman of the Rockefeller Family Fund,  None of the Republican members have uttered a word in favor of carbon taxing, even the intendedly Republican-friendly “fee and dividend” espoused by the caucus’s catalyst,

None of the Republican members have uttered a word in favor of carbon taxing, even the intendedly Republican-friendly “fee and dividend” espoused by the caucus’s catalyst,  Nevertheless, Issa and the caucus’s other lame-duck Republican members have a rare opportunity: a full year still in office to speak their minds on climate (or other issues) without fear of being primaried by unabashedly denialist insurgents. They could push back against Trump’s climate lies and call on their party to assume its Rooseveltian mantle of environmental stewardship. In doing so, they could set a standard for their 28 Republican colleagues who hope to keep their seats and, by their caucus membership, have ostensibly committed themselves to pursuing climate solutions.

Nevertheless, Issa and the caucus’s other lame-duck Republican members have a rare opportunity: a full year still in office to speak their minds on climate (or other issues) without fear of being primaried by unabashedly denialist insurgents. They could push back against Trump’s climate lies and call on their party to assume its Rooseveltian mantle of environmental stewardship. In doing so, they could set a standard for their 28 Republican colleagues who hope to keep their seats and, by their caucus membership, have ostensibly committed themselves to pursuing climate solutions. Congestion pricing levies fees on vehicle travel into or within the core of a city. Singapore,

Congestion pricing levies fees on vehicle travel into or within the core of a city. Singapore,

The trope

The trope  Lifton, a psychiatrist who turned 90 last year, has long observed, lived among and written about the perpetrators and victims of some of the 20th Century’s most profound atrocities — the atomic bombings of Japan, the Vietnam War and, of course, the Nazi Holocaust. His writing humanizing the

Lifton, a psychiatrist who turned 90 last year, has long observed, lived among and written about the perpetrators and victims of some of the 20th Century’s most profound atrocities — the atomic bombings of Japan, the Vietnam War and, of course, the Nazi Holocaust. His writing humanizing the