The U.S. 2022 Inflation Reduction Act is intended to reduce carbon emissions in vehicular travel and other economic sectors through a broad range of energy incentives and subsidies led by measures to reduce the cost to manufacture and sell electric vehicles. This page links to coverage of the IRA and explores its likely implications for both carbon emissions and the project to enact economy-wide carbon taxes in the U.S.

Biden Administration Detailed Guide to the IRA

In December 2022 the White House released a 182-page guide to the energy and climate provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act. Building a Clean Energy Economy: A Guidebook to the Inflation Reduction Act’s Investments in Clean Energy and Climate Action is a 15 MB pdf.

Introduction

In a head-spinning 20-day legislative whirlwind from late July to mid-August, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 was unveiled by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin, passed by the Senate and the House, approved by the Senate parliamentarian (and thus immunized against the filibuster), and signed by the President.

In the climate-policy firmament, the Inflation Reduction Act could be seen as an antithesis of carbon pricing. Rather than making dirty (fossil) energy costlier in the marketplace, it seeks to make clean energy cheaper by subsidizing low- or zero-carbon power sources. It also aims to leverage low-carbon electricity by paying vehicle and building owners to switch to electric power from combustion fuels that can’t themselves be decarbonized.

Nevertheless, the “IRA” stands as a landmark legislative achievement — the most ambitious as well as costliest federal initiative to reduce carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, the affirmative nature of the legislation — “upending the debilitating narratives of U.S. climate helplessness and Biden-Democratic Party haplessness,” as we wrote in early August in a post in The Nation (cross-posted here as well) — could some day open the door to federal legislation pricing carbon emissions.

What the Inflation Reduction Act Does

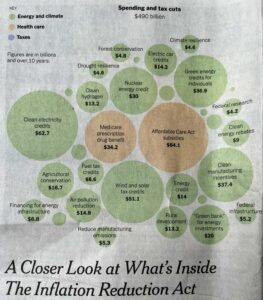

The IRA (download summary or full text) commits $370 billion in federal subsidies over the next decade to bring down the cost of “clean” (ultra low- or zero-carbon) energy and accelerate the electrification of U.S. vehicles, buildings and industry so that increasingly low-carbon power displaces carbon-spewing direct combustion of oil and gas. The designated spending pots are depicted in the New York Times graphic below.

NY Times Aug. 17, 2022 graphic depicts projected IRA spending pots over the next ten years.

Another section of the omnibus legislation authorizes the federal government to negotiate down prescription drug prices and expands subsidies for health insurance under the Affordable Care Act — measures intended to bolster and expand the Obama administration’s signature “Obamacare” legislation and also situate climate legislation in a more popular context. And, in a potentially important precedent, the IRA sets in motion a greenhouse gas fee — not on CO2 but on “excess” methane emitted from oil and gas extraction and transportation infrastructure — to take effect in 2024.

Passage of the IRA ended a protracted period of U.S. backsliding from climate action. It also fulfills, if only as a first, albeit major, step, campaign commitments by Joe Biden and other national Democrats to tackle U.S. emissions and climate change. Its enactment was viewed as boosting the Democratic Party’s chances a retaining control of Congress in the 2022 midterms. [Post-election addendum: the Democrats did in fact surpass expectations in the Nov. 2022 voting, increasing their Senate majority by one and limiting their House losses to nine, though that was enough to flip control to the Republicans.]

This page presents and distills informed commentary on and analysis of the Inflation Reduction Act. We hope to soon tend to the legislation’s implications for advancing comprehensive, national-level U.S. carbon pricing.

A veteran journalist’s take: “It makes clean energy cheap.”

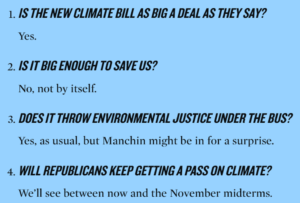

An excellent early entry point into the IRA is from the pen of veteran journalist Mark Hertsgaard. His Aug. 11, 2022 essay in The Nation, Does The Climate Bill Throw Environmental Justice Under The Bus?, touted the legislation as by far the biggest pro-climate policy by the U.S. or any other country, while making clear that it’s not enough by itself.

Mark’s piece is worth quoting at length, especially up front, where he said, Yes, the legislation is a big deal:

“It makes clean energy cheap, that’s the bottom line,” said Jesse Jenkins, an engineering professor at Princeton who conducted independent modeling of the spending. New federal money, often in the form of tax credits, will subsidize consumers who switch to electric vehicles or install heat pumps and other energy efficient household technologies. It will incentivize electric utility companies to shift from gas to renewables and oil and gas companies to minimize leaks of methane, an exceptionally potent greenhouse gas. It will pay to clean up America’s ports, a concentrated source of emissions that not only overheats the planet but poisons nearby communities, which tend to be disproportionately poor and people of color.

By doing all this and more, the Inflation Reduction Act will create 9 million jobs over the next decade in clean energy, clean manufacturing, and natural infrastructure (e.g., forests and parks), according to the Blue Green Alliance. The bill’s backers further assert that it will reduce annual US emissions by 40 percent from 2005 levels by 2030, a claim supported by three independent analyses that is further examined below. If achieved, that reduction would approach the 50 to 52 percent reduction that scientists say is needed to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

(We at Carbon Tax Center are less sanguine about 2030, in part because we question the apparent modeling assumption that the U.S. was already on track for a 30 percent reduction by 2030; U.S. 2021 emissions were only 14 percent below the 2005 baseline figure, not 20 percent, a figure calculated with 2020 emissions, an obvious aberration due to temporary Covid-related economic and energy contractions, yet one advanced by a high-profile NY Times climate columnist in May and repeated a month later in a NYT editorial. Note also that the bill’s backers didn’t credit the IRA with reducing U.S. emissions by 40 percent; rather, they pointed to the bill as a big assist to accomplish that job, tacking a high single-digit reduction onto that putative 30 percent “business-as-usual” reduction level.)

That’s another reason this bill is a big deal: It gives the United States much-needed credibility to urge other countries to slash their own emissions. The U.S. has taken many big steps on climate over the years, just mostly in the wrong direction. Instead of cutting emissions, it boosted them through subsidies and lax regulations. It has repeatedly cast doubt on whether there is even a problem, with the last president calling climate change “a hoax” to applause from fellow Republicans. At international conferences dating back to the Earth Summit in 1992, the same script has played out again and again: Other big emitters that don’t want to cut back hide behind the U.S. refusal to do so. If the Inflation Reduction Act becomes law, that dodge will no longer be credible.

Hertsgaard’s Q&A. On #3 (EJ), the legislation may be stronger than the graphic suggests.

Hertsgaard put G.O.P. climate obstructionism in a harsh light, asking “How much longer will the Republican Party be given a pass on its climate wrecking?” Here’s his answer:

Until Manchin’s surprise announcement that he was ready to support a climate bill after all, both wings of the movement, along with 99 percent of press coverage, was giving him all the blame for blocking climate progress on Capitol Hill. This was understandable, but bizarre given that his vote only mattered because Republican senators have been in lockstep opposition to climate action since, well, forever. Republicans in Washington have opposed real climate action for more than 30 years … Yet they never pay a political price for it. News coverage and political adversaries treat the GOP’s opposition as unchangeable as gravity. Thus Republicans get away with scorning Democrats’ ideas for combating the climate crisis, even as they offer no credible plans of their own. (emphasis added)

“No more hiding behind a free pass,” Hertsgaard wrote, as he called on climate activists to challenge climate-do-nothing Republicans, not a single one of whom voted for the IRA, in midterm campaigning. Alongside parallel challenges to regain reproductive autonomy and stop deranged 2020 election conspiracy-mongering, the Democrats’ newfound climate voice just might give them a fighting chance to hold Congress in November. [Note addendum above, reporting the Democrats’ greater-than–expected electoral strength in the 2022 midterms.]

Perhaps the most intriguing part of Hertsgaard’s article was his discussion of the IRA’s environmental justice implications. He gave EJ advocates, from environmental justice godfather Robert Bullard to the upstart Climate Justice Alliance (whom we called out on our Carbon Pricing and Environmental Justice page), plenty of space to decry the provisions nominally authorizing more drilling and other fossil fuel extraction, which historically has disproportionately damaged BIPOC communities. But Hertsgaard also spotlighted the assertion by the consultancy Energy Innovation (one of the three bullish “independent analysts” of the IRA noted earlier) that “the bill’s clean energy measures will yield 24 times more emissions reductions than its fossil fuel provisions will increase emissions.” [Addendum, Sept 2023: Energy Innovation subsequently raised its 24-to-1 emissions ratio to 28-to-1; details here.]

This claim, even if only half-valid, could be catalytic, as Hertsgaard explains:

That 24-to-1 ratio hints at why the bill’s environmental justice impacts might be less destructive than predicted. The fundamental strategy behind this bill is to make clean energy dramatically cheaper — so much cheaper that fossil fuels are squeezed out of existence, not by government fiat but by the workings of the marketplace.

Let’s go ahead and say what Hertsgaard only hinted: Environmental justice stands to win enormously under the Inflation Reduction Act. Not just from the millions of new jobs. Not just from its down payment against climate pollution that disproportionately threatens communities of color from the US to the Global South. And not just from “the good things in it,” per Prof. Bullard, “that are greatly needed by low-income, people of color and environmental justice communities — such as incentives for clean energy technologies, electric vehicles, school buses and transit; helping families who are energy insecure with their electric bills; retrofits and tax credits to assist with making homes more energy efficient; and targeted investments to address legacy pollution and environmental ‘hot-spots’ created by racial redlining.”

All these matter greatly. But the big EJ payoff from the IRA will come from reducing the “need” to extract and process fossil fuels, by strangling the source: demand.

The omission of this point by the many EJ activists and allies whom Hertsgaard interviewed or cited — not just Bullard and the Climate Justice Alliance but also Greenpeace USA co-director Ebony Martin and Erich Pica of Friends of the Earth — raises an intriguing question: If it is true that climate justice campaigners downplay or ignore policy legislation that, at least on paper, seems destined to reduce extractive and exploitative pressures on communities of color, is it because they regard connections between demand and extraction as tenuous or even chimerical? Or is it because their movement is built on solidarity (see for example the 1991 founding Principles of Environmental Justice) and thus they cannot countenance sacrifice by a few (if indeed it’s only “a few”) for the benefit of the many communities that will be spared because the large-scale restructuring of energy demand will allow the plague of extraction or exploitation to pass over them?

Fabulous Weeds: The Jesse Jenkins Interview by David Roberts

Our heading references “The interview” because this podcast conversation achieved cult status among climate and energy policy types. We say “Weeds” because the 72-minute podcast went deep into the workings of the IRA. And we say “Fabulous” because Jenkins’ command of the intricacies of the legislation and their implications — for U.S. energy supply and use, for emissions and climate, and for the surrounding politics — is nothing short of brilliant. In this conversation the weeds sway and sing.

Roberts, a veteran political + energy + climate journalist whom we have followed closely (and occasionally tangled with) for more than a decade, posted his conversation with Jenkins, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Princeton, on Aug. 19 as Diving further into the Inflation Reduction Act: Part Two.

Among the topics covered and the points made:

- The IRA greatly liberalizes companies’ and non-profit organizations’ ability to sell clean electricity tax credits earned from renewable investments, thus expanding capital pools to finance clean power.

- New zero- or low-carbon generating facilities located in transitioning fossil fuel communities and on Indigenous lands receive extra tax credits. The same applies to electric vehicle and battery component manufacturing plants.

- Unionized manufacture likewise receives greater tax advantages, as do vehicles and batteries manufactured with especially high domestic content.

- Wind and solar projects are guaranteed tax credits for an entire decade (to 2032), thus removing an habitual source of uncertainty that had helped bottle up clean energy supply. The time horizon is lengthened even further as long as the U.S. falls short of 75% electricity decarbonization from today’s level.

This brief list barely scratches the surface of the details enumerated by Jenkins. “It’s like a roulette wheel that just happened to settle out at a decent place at just the right moment,” enthuses Roberts, marveling not just that Manchin climbed aboard the legislative train at all but that seemingly every smart nudge ever dreamed up by Congressional Democrats and their staff made it into the bill that got passed.

Politics of clean energy subsidies vs. carbon taxes

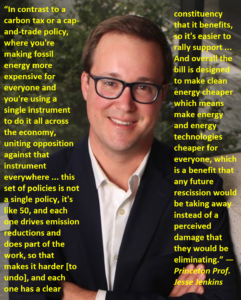

Princeton’s Jesse Jenkins on why the Inflation Reduction Act’s clean-energy subsidies are likely to prove durable, even impregnable.

For carbon tax proponents, the podcast’s signal moment comes just before the close, at the one hour, six minute mark, when Roberts asks Jenkins how durable he thinks the IRA policies and programs in the Inflation Reduction Act will be “in the nightmare scenario in which [climate-uncaring] Republicans pull off a trifecta in 2022 and 2024″ and gain power.

Jenkins’ answer, which we’ve put in the graphic at left, is worth pondering. And unlike Roberts, who has the same outlook, Jenkins seems to state his with no animus against carbon pricing, which makes his view even more important.

“Over the next decade there will be hundreds of billions of new tax revenues tied to these [clean-energy] facilities,” says Jenkins, “and dozens and dozens of new factories, there will be over a million new jobs in manufacturing and a million more in installation and construction and maintenance … and they will be spread all over the country and they will be … driven specifically into energy communities that have traditionally been tied to the fossil energy economy, and so their affiliation with and self-interested ties to the fossil economy may not be eliminated but will certainly be complicated over time.”

“Moreover, [the IRA] will deliver very near-term salient environmental health benefits, particularly to environmental justice communities … that will be felt in the short term way before we can see any signal in the climate chaos that is unfolding around us. [Which makes the legislation] more economically durable, instead of delivering a backlash that has to be defended against,” in the case of a carbon emissions price.

If you try to repeal any of the provisions of the IRA, Jenkins says, “You’re going to have billion-dollar companies lined up to fight you because they’re making money off of this [and you’ll have] local elected officials pissed off because you’re jeopardizing investments in their districts. It’s just not a good idea,” he concludes, to try to roll back the legislation.

“A constituent creation machine,” Roberts calls the Inflation Reduction Act, “shooting money out every which way.”

We find Jenkins’ (and Roberts’) viewpoint cogent, though more as a defense of the IRA than a final nail in the carbon-tax coffin. We hope to say more on this score soon, in this space.

Red States’ IRA Windfall

It shouldn’t be surprising that investment in green-energy infrastructure is concentrated in Republican-leaning states and counties. Solar arrays and, especially, wind farms are land-intensive and, as Republicans never tire of pointing out, the area of U.S. counties that voted for Trump over Biden in 2020 was triple the area that went for Biden. Manufacturing too is more prevalent in rural areas, relative to population, than urban.

Still, it’s startling how much of new investment in green energy is taking place in what is considered “red” voting territory. An August 2023 preliminary analysis by the Treasury Department reports that more than 80 percent of IRA-related investments are in areas with below-average college graduation rates. Around 65 percent are in areas with above-average poverty rates, and the same share, 65 percent, are in areas with below-average employment levels. Even more striking is that almost 90% of the announced investments are in counties with below-average weekly wages. (Percentages are based on 2021 data; hat tip to New York Times columnist David Brooks, who featured these figures in his Sept 7, 2023 column, The American Renaissance is Already at Hand.)

This is pork-barrel politics with a twist, or, at least a wide purview. The Biden administration’s hope is that the anticipated surge in green energy and reductions in carbon emissions will resonate with climate-concerned urban and suburban voters while the job benefits for red-leaning areas will entice some vote switches there. (The Treasury Dept. should also express its data in absolute terms to allow a sense of the strength of the employment effects.) Some cutting-edge political commentators disparage this, of course, based on anecdotal plus polling evidence that the IRA has yet to register with the electorate. Even so, the IRA facts on the ground, which will only grow with the passage of time, should help to inoculate the legislation against Republican roll-back efforts.

Lording It Over Carbon Pricers

We were taken aback that veteran climate writer (formerly NY Times, now Energy Innovation) Justin Gillis didn’t just badger carbon tax proponents to get aboard the “Make Clean Energy Cheap” train but also blamed our ilk for “the most epic wrong turn in the history of climate policy,” one that, in his telling, delayed passage of the Inflation Adjustment Act for decades.

Sure, if you believe the kind of industrial policy brilliantly written into the Inflation Reduction Act can decarbonize the U.S. economy in a decade or so? We’re doubtful.

Goodness! Whatever happened to magnanimity in victory? Not to mention historical accuracy. Fact is, climate policy hit a dozen-year wall after 2010 not because carbon taxers held sway in climate discourse — believe me, we did not — but because Tea-Party Republicans took over Congress. As for the 1990s, climate policy’s failure to lift was more because climate dangers appeared hypothetical, a mere speck on the horizon, than because of the long shadow cast by Clinton’s failed 1993 Btu tax.

Even in the in-between decade of 2000-2010, carbon taxing never got a real shot in Congress. The big green groups, seeking to duplicate the success of the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments creating the SO2 trading system, and determined to “hide the price” rather than level with Americans over the true costs of cheap fuels, insisted on the convoluted, Wall Street-tinged, devilishly complex cap-and-trade approach, only to see it crash and burn under its immense weight. The rightward, xenophobic cultural shifts that arose after 9/11 hurt as well, as did eight years of oil-allegiant George W. Bush and Dick Cheney.

Moreover, it is only fairly recently that zero-carbon energy became readily available at prices low enough to allow them to scale rapidly and massively without subsidies that would blow up the national debt (remember that bugaboo?). Arguably, the wind and solar sectors also had to be granted time to edge far enough into the mainstream that an industrial policy built on subsidizing them into ubiquity wouldn’t meet with widespread ridicule.

All of which is to say that what started as Build Back Better and eventually became the Inflation Reduction Act probably couldn’t have come into fruition until now. Sure, David Roberts — he of the Jesse Jenkins podcast celebrating the IRA — presaged the theory behind that legislation in mid-2020, with his Standards-Investment-Justice formulation (which we dutifully praised at the time in our post, If the Democrats Run the Table in November). But it’s a hell of a stretch to argue, as Gillis did on Twitter, that something like the IRA could have been conceived and enacted a lot sooner if not for people “who chased the will-o-the-wisp of a carbon tax for 30 years.”

As for Recalculating on Climate, Lydia DePillis’ NY Times commentary Gillis was touting, the less said the better. Not for the first time, it conflates nominal carbon pricing proponent Bill Nordhaus with climate-damage modeler Bill Nordhaus whose blinders about global climate chaos’s prospective toll on ecosystem services and economic productivity contributed greatly to the economic profession’s persistent lowballing of the likely costs of unchecked fossil fuel emissions.

The second headline of DePillis’s piece, “They underestimated the impact of global warming, and their preferred policy solution floundered in the United States,” is true enough. But while it was perhaps inevitable that a piece of this sort would lead with Nordhaus, winner of the 2018 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, it was off-pitch to place him at the center of carbon tax advocacy. To its credit, the article granted space for Columbia Business School climate economist Gernot Wagner to point out that Nordhaus’s proposed “optimal carbon price” of just $43 per metric ton in 2020 was and is a “woeful underestimate of the true cost.”

(For CTC’s brief and partly laudatory commentary on Nordhaus’s 2018 Nobel, see our post, From Sweden, A Deeper Dive Into Last Weeks’ Economics Nobels. For a deeper and more critical look, see our 2017 post, Showing the Cost Side of the Climate Equation in a New Light.)

Perils of Making Clean Energy Cheap

“The [IRA] is designed to make clean energy cheaper which means mak[ing] energy and energy technologies cheaper for everyone.” That’s Princeton energy savant Jesse Jenkins, speaking with podcaster David Roberts just after the Inflation Reduction Act was signed into law in August 2022 (quote excerpted from earlier graphic).

The political benefits of making clean energy cheap are clear: It creates large, diverse constituencies strong enough not just to enact the subsidies but to maintain them through shifting political winds. Moreover, monetary firepower from the clean-energy subsidies can help counter NIMBY pressure to block the new wind farms, solar arrays and transmission lines needed to generate the clean power and to help bring into being the supply chains (mines, factories, etc.) needed to crank out the hundreds of millions of vehicles and appliances needed to replace the incumbent ones that run on fossil fuel combustion.

That’s the political logic and the vision behind the IRA, which Jenkins and Roberts depict so alluringly. But it comes with a potentially large downside: more total energy consumption, not less. That’s because the artificial lowering of energy prices — artificial because the wind and solar facilities and allied infrastructure will be heavily subsidized — will militate against efficiency investments and choices.

EV subsidies probably won’t make right-wing radio guy Erick Erickson drive more. But they definitely won’t motivate him to drive less.

How? The subsidies that make the IRA work politically will tend to weaken the micro-economic case for virtually every conservation investment, from HVAC upgrades and moderately sized homes to increased residential density and less-car-dependent street designs. That’s due to longer payback periods and worsened benefit-cost ratios stemming from the reduced monetary value of the saved energy.

In addition to lesser conservation investment, conservation behaviors such as driving less, re-using more and just plain lowering consumption will similarly be buffeted by the powerful tide of cheaper energy. And while it’s true that carbon- and climate-mindful behavior has never gained much of a foothold in the U.S., cheap energy will further discourage it.

The IRA’s bending of consumption curves toward more overall energy use rather than less might not matter much if complete grid decarbonization could be accomplished quickly and with little ecosystem and community disruption. After all, why fret about energy overuse if (i) all of the energy is electric, and (ii) all of the electricity is ultra-low or zero carbon, and (iii) installing and deploying those seemingly benign electricity sources and the devices that use them (EV’s, heat pumps, etc.) don’t unduly damage nature and communities?

The answer is that none of those three conditions will be met anytime soon. And the day on which all three obtain is way out on the horizon, if at all.

The Methane Fee

The Inflation Reduction Act includes a fee on “excess” methane emissions from oil and gas extraction and processing. The fee looks to be impactful not only on future methane emissions but as a potential stepping stone to possible carbon emission fees.

The text box at right, courtesy of the Akin Gump law firm, contains key details but little context. We hope soon to add metrics indicating the fee’s “bite” including projected revenue and estimated impact on emissions.

The Transmission Trap

The vast buildout of renewable capacity that the Inflation Reduction Act is intended to catalyze won’t happen without two enormous, complementary developments: easier and quicker siting of wind, solar and battery installations; and accelerated construction of large-scale electric transmission lines to connect those installations to power grids and also better interconnect the nation’s disparate power grids to each other.

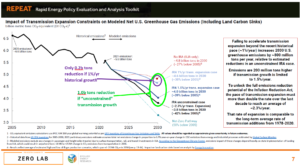

Underscoring transmission’s critical importance, in September 2022, just a month after the IRA was signed into law, the law’s most prominent modeler and proponent, Jesse Jenkins (see his interview with journalist David Roberts, above), acknowledged in an elaborate slide deck that failure to accelerate the historical rate of U.S. transmission buildout would cancel 80 percent of its emission reductions he projected for 2030.

We’ve embellished the Jesse Jenkins team’s key slide. As our large-type text notes, the full-potential GHG reduction of 1.0 billion tons a year in 2030 (shown in green) shrinks to just 0.2 billion (purple) unless the historical rate of electric transmission capacity is boosted sharply.

Jenkins’ key chart on the consequences of stalled transmission capacity growth is copied at left, with our embellishments. The takeaway: subsidizing green energy, even via the enlightened, innovative paths in the Inflation Reduction Act, is no panacea. Enacting a U.S. robust carbon tax is hard, obviously, but attacking climate change without carbon pricing has its own pitfalls, and they’re not incidental.