Former 4-term California governor Jerry Brown, in Los Angeles Times climate reporter Sammy Roth’s Aug. 4 “Boiling Point” column, Jerry Brown was surprised — and thrilled — by Joe Manchin’s climate deal.

Pricing carbon efficiently and equitably

Former 4-term California governor Jerry Brown, in Los Angeles Times climate reporter Sammy Roth’s Aug. 4 “Boiling Point” column, Jerry Brown was surprised — and thrilled — by Joe Manchin’s climate deal.

NY Times columnist Paul Krugman, in Why Republicans Turned Against the Environment, Aug.15.

[Our new page, The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, has much more on the legislation spawned by the Manchin-Schumer deal — what it will and won’t do to emissions, what it means for climate policy, and whether it closes or opens future paths for carbon pricing. — Sept. 1, 2022]

To access this post’s original version in “The Nation,” use link at top of text.

The Nation magazine this morning published my essay, The Manchin-Schumer Deal Could Pay Off—If Congress Acts. I’ve cross-posted it here to allow comments and add graphics for context.

While the deal assiduously, and regrettably, leaves intact the deep, intertwined roots of U.S. fossil fuel dependence, it’s imperative to support it — not just for its beneficial, albeit indirect, impacts on emissions, but because of its potential to materially improve both climate dynamics and political dynamics in the U.S.

Our Comments are open. Let us know what you think.

— C.K., August 2, 2022

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 will knock out less than 10 percent of U.S. climate pollution by 2030, leaving the nation short of even its whittled-down goal of getting emissions 40 percent below the 2005 level.

Why, then, are many climate activists popping champagne corks? And why should progressives of every stripe do likewise? It’s simple. If the deal between Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin survives more or less intact, it will upend two deeply debilitating narratives: U.S. climate helplessness and Biden-Democratic Party haplessness.

The haplessness first: The legislation should help dispel the aura of fractious Democrats incapable of doing what we elect them to do: deliver big structural change. This turnabout could boost the Dems’ chances of retaining or even expanding control of Congress in the midterms, making possible not just other climate wins but also gains on voting and reproductive rights, economic justice, and the rest of the progressive agenda we hold dear.

The Inflation Reduction Act likewise marks a turning point, at least for the time being, on long-running, world-damaging U.S. climate helplessness. True, modeling by the Rhodium Group found that the legislation will only deliver a 7 to 9 percent carbon reduction relative to ongoing trends—far short of the massive cuts required for the United States to credibly claim global climate leadership. But by letting millions more Americans experience wind, solar, and energy efficiency—not as abstractions but as palpable engines of economic advancement—the bill opens paths to expansive climate gains going forward.

The Inflation Reduction Act likewise marks a turning point, at least for the time being, on long-running, world-damaging U.S. climate helplessness. True, modeling by the Rhodium Group found that the legislation will only deliver a 7 to 9 percent carbon reduction relative to ongoing trends—far short of the massive cuts required for the United States to credibly claim global climate leadership. But by letting millions more Americans experience wind, solar, and energy efficiency—not as abstractions but as palpable engines of economic advancement—the bill opens paths to expansive climate gains going forward.

The omnibus legislation also burnishes green energy investments by packaging them with other popular but less threatening reforms such as affordable prescription drugs and higher taxes on big corporations. Not to mention the chef’s kiss of the bill’s name, the Inflation Reduction Act, signaling Democrats’ attentiveness to this year’s hot-button issue.

Admittedly, this is a lot to hang on a bill that doesn’t directly tackle the entrenched, intertwined systems that have long locked in Americans’ profligate carbon consumption: massively overbuilt roads, decrepit public transit, low-density zoning, anti-urban bias, rampant inequality, and artificially cheap fossil fuels. But, to borrow from Auden, such are our low, dishonest politics. No bill addressing even one of those matters was ever going to pass this Congress, with the modest exception of a fee on “excess” methane leaks from oil and gas wells and pipelines, starting in 2024.

A mailing from the antinuke Nuclear Information & Resource Service proclaims the legislation’s reactor-preservation provisions “will fail to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by any amount.” Really? The recent shutdown of New York’s Indian Point reactors has increased statewide CO2 emissions by a whopping 8 million metric tons a year.

Instead, we get three big, complementary though indirect ways to cut emissions: monetary rewards for wind, solar, and nuclear—yes, nuclear—generators that make electricity without burning fossil fuels; bigger tax credits to purchase electric automobiles and accelerate the demise of fossil cars and trucks; and tax breaks for US factories to manufacture those new wind turbines and solar arrays.

If much of that sounds technical, wait till you hear Rhodium explain that the Inflation Reduction Act will let clean-energy developers transfer their tax credits to third parties that “have tax liability and [thus] the ability to monetize the credits.” The 700-page bill abounds with just such tools to crack open long-standing bottlenecks impeding the shift to clean energy.

The legislation also swarms with fossil-fuel concessions, most notably a requirement that the Interior Department auction off more public lands and waters for oil drilling. The Center for Biological Diversity last week labeled that provision a “climate suicide pact … that will fan the flames of the climate disasters torching our country [and deliver] a slap in the face to the communities fighting to protect themselves from filthy fossil fuels.”

Fossil fuel extraction and processing are indeed filthy and toxic. But expanding U.S. leasing will worsen total warming only slightly. Since fuels are fungible, stopping one carbon source leads Big Oil to tap supply somewhere else. Rather, by cutting overall demand for fossil fuels, the Inflation Reduction Act “will make oil leasing less profitable and therefore less widespread,” as UC Santa Barbara environmental politics professor Leah Stokes noted last Friday on Democracy Now. Fewer communities overall will be ravaged by drilling, let alone floods and other climate havoc.

People complaining about the provision in the #InflationReductionAct that allows for more drilling on federal lands have a VERY different counterfactual than I do. It would almost be like me complaining there is no carbon tax in the bill…#ClimateCrisis #ClimateAction

— Christopher Knittel (@KnittelMIT) July 29, 2022

Let’s also credit the Manchin-Schumer deal’s potential to leverage U.S. emission cuts by palliating our global climate disrepute, a point long made by Senator Edward J. Markey (D-MA), who along with Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and the Sunrise Movement, is widely credited with elevating the Green New Deal into political discourse. “You can’t preach temperance from a bar stool,” Markey said in 2008, adding last week that “you can’t ask China, India, Brazil or other countries to cut emissions if we’re not doing it ourselves in a significant way.”

While we shouldn’t over-credit the immediate carbon reductions from the Inflation Reduction Act, it’s imperative to close ranks behind it, as MIT climate economist Christopher Knittel urged on Twitter last week: “People complaining about the provision in the Inflation Reduction Act that allows for more drilling on federal lands have a very different counterfactual than I do. It would almost be like me complaining there is no carbon tax in the bill.”

Knittel’s counterfactual, of course, was U.S. climate stasis. Mine was as well, along with Democratic Party squabbling. That may have changed last week. We must make the most of it.

Charles Komanoff, a longtime environmental activist, directs the Carbon Tax Center.

Addendum: The Inflation Reduction Act includes a fee on “excess” methane emissions from oil and gas wells and pipelines of $900 per metric ton of emissions above new federal limits in 2024, increasing to $1,500 per metric ton in 2026. MIT economist Chris Knittel (quoted above) equates the $900 methane fee to $60 per metric ton of CO2, a level that would qualify as a fairly robust nose in the proverbial camel’s tent of carbon pricing.

Letter to editor by Tom Miller of Oakland, Calif., published in New York Times, July 19.

A New York Times post this week, Biden’s Climate Change ‘Revolution’ Isn’t Coming, caught our attention with its trenchant look at climate policy’s low ebb in the wake of two crushing setbacks in just three weeks: the June 30 Supreme Court ruling blowing up EPA’s carbon-regulating authority under the Clean Air Act, and Joe Manchin’s coup de grace to the remnants of President Biden’s Build Back Better climate package.

Drawing on fellow Times writers, opinion editor Spencer Bokat-Lindell painted an unsparing portrait of U.S. — and global — climate stasis as dangerous heat was enveloping Britain, much of Europe and large swaths of the U.S. Here we reprint his post in full, with our commentary as counterpoint.

Biden’s Climate Change ‘Revolution’ Isn’t Coming.IntroductionWhen President Biden took office, one of the first things he did was make a pledge: The United States, he vowed, would finally “meet the urgent demands of the climate crisis” through “a clean energy revolution.” That revolution was to be set in motion by a $2 trillion plan for putting the country on a path to 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2035 and to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, in line with the Paris agreement’s goal of keeping global warming well below 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit above preindustrial levels. (It now stands at 2.2 degrees.) But after more than a year of negotiations, compromises, deal-making and belt-tightening, that plan appeared to collapse last week when Senator Joe Manchin, a conservative Democrat from West Virginia and a key swing vote in Congress, announced that he would not support funding for climate or energy programs. What does the collapse of Biden’s agenda mean for the domestic and global politics of climate action moving forward? Here’s what people are saying. |

Biden’s Plan, Though Not Revolutionary, Was Bold.Introduction

(Chart is from CTC Sept 2021 post, Without a Carbon Tax, Don’t Count on a 50% Emissions Cut.) |

1. The climate deal that wasn’tAs my colleagues have reported, experts generally agree that there are two ways of reducing greenhouse gas emissions at the speed and scale required. The first is making fossil fuels more expensive by ensuring that their environmental costs — global warming, for one, but also the staggering harms of air pollution — are reflected in their price. While widely championed by economists, carbon taxes have proved politically unpopular: A carbon tax by ballot referendum in Washington State has failed twice. Biden hoped to take the other approach: reducing emissions by driving down the cost and improving the efficiency of low-carbon energy sources, like wind, solar and nuclear power. Initially, the centerpiece of his plan was a clean energy standard, which would have legally required utilities to draw 80 percent of their electricity from zero-carbon sources by 2030 and 100 percent by 2035. But when Manchin — who made millions from his family coal business and took more campaign money from the oil and gas industry than any other senator — pulled his support from that scheme in October, Democrats pivoted to a $300 billion package of tax credits to encourage the adoption of renewable energy and electric vehicles. Now, both avenues to decarbonizing the country have been all but closed off. Even before Biden’s plan was whittled down, there was some debate about whether it was sufficient to meet his ambitions. But now that the president’s most powerful tools for reducing emissions have been confiscated by Congress (and the Supreme Court, which last month limited the power of the Environmental Protection Agency to regulate power plant emissions), “We are not going to meet our targets, period,” said Leah Stokes, a professor of environmental policy at the University of Santa Barbara, California, who has advised congressional Democrats on climate legislation. Manchin’s reason for scuttling the negotiations, according to his spokeswoman, was his desire to “avoid taking steps that add fuel to the inflation fire.” But in The Atlantic, Robinson Meyer argues that, in addition to being “extraordinarily bleak for the climate,” Manchin’s reversal will actually worsen inflation: By reducing long-term demand for oil, Biden’s plan would probably have lowered gas prices, and an earlier version of the package would have led to hundreds of dollars in annual energy cost savings for the average U.S. household by 2030, according to an independent analysis from researchers at Princeton. “America’s climate negligence endures,” Meyer writes. “That is not just due to Senator Manchin’s negligence, of course. It is also the collective responsibility of the Republican Party, whose 50 senators are even more resolutely against investing in clean energy than he is.” |

1. The long shadow of Washington state’s failed carbon tax referendumBokat-Lindell could have said, about carbon taxes, that they are widely championed by economists and others who judge robust carbon taxing as uniquely capable of delivering big emission cuts quickly. Still, his characterization of carbon taxes as politically unpopular was fair. He was also on solid ground in pointing to the failed Washington State carbon tax referendum. Perhaps even more than Donald Trump’s concurrent electoral win over Hillary Clinton, the 2016 defeat of Initiative 732 put a hurt on U.S. carbon tax organizing and advocacy. After all, if a carbon tax couldn’t garner an electoral majority in a certified blue state — one with a strong outdoors-nature ethic to boot — it was likely to be a tough sell almost anywhere else.

Fast-forwarding to 2021-2022, it’s also fair to ask why climate activists trained virtually all of their fire on Joe Manchin, perhaps not grasping that his personal and political indebtedness to fossil fuels — duly noted by Bokat-Lindell — placed him beyond their reach. As The Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer notes, 50 Republicans blocked Biden’s climate package no less than Manchin. Protests in their home states might have moved the legislative needle or at least thrown down a marker to preserve Democrats’ control of Congress in the coming midterms. |

2. A domestic defeat with global consequencesBecause the United States has spewed more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere than any other nation, it plays a uniquely prominent role in global climate politics. (It’s worth noting that on an annual basis, China is now the world’s largest emitter, having surpassed the United States in 2006, though America’s per capita emissions still far exceed China’s.) Given the United States’ historical “climate debt,” many lower-income countries have made their climate commitments contingent on those of the United States and other rich countries. Especially after Donald Trump withdrew from the Paris agreement, many world leaders were hopeful that Biden would arrive at the Glasgow climate talks last year having secured some legislative achievement as a mark of political seriousness. That, of course, did not happen. Now, the United States’ international climate credibility is even more damaged, which will in turn impede global decarbonization efforts, The Times’s Somini Sengupta writes. “Manchin’s rejection and the recent Supreme Court ruling dealt a heavy blow to U.S. climate credibility,” Li Shuo, the Beijing-based senior policy adviser for Greenpeace East Asia, told her. It underlines what many people abroad already know, Li said: that “the biggest historical emitter can hardly fulfill its climate promises.” The U.S. climate envoy, John Kerry, is expected to attend the next round of climate talks, in November in Egypt, but will once again have little to show for it. The United States “will find it very hard to lead the world if we can’t even take the first steps here at home,” said Nat Keohane, the president of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, an environmental group. “The honeymoon is over.” |

2. Goodbye to the myth of U.S. global leadership on climateWe noted upfront that in addition to their sheer numerical weight, Build Back Better’s carbon reductions would have triggered parallel policies in other countries. Bokat-Lindell articulates this well, with framing that, appropriately, prioritizes U.S. climate stewardship as “necessary” rather than merely “sufficient.” What would translate almost automatically from the domestic sphere to the global is U.S. federal-level carbon taxing. The simplicity of a national carbon price alone makes it child’s play to replicate it in any other country — in marked contrast to the welter of tax credits, rules and line items embodying Biden’s climate plan that would be devilishly hard if not downright impossible to copy elsewhere. Moreover, the logical companion piece to a national carbon tax — a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism — would powerfully incentivize non-carbon-taxing countries to enact their own in order to capture for themselves carbon tax levies that otherwise would be collected by their carbon-taxing trading partners. That said, the various stories and authorities cited in the Times column have it exactly right. The heavy weight of America’s outsize cumulative carbon emissions, combined with what now must be seen as chronic federal government inaction — aptly summarized by Greenpeace as (“the biggest historical emitter can hardly fulfill its climate promises”) — expose the U.S. as climate laggard rather than leader. Unfortunately, that fact didn’t keep U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC), who once supported carbon pricing via cap-and-trade (see this 2009 op-ed in the New York Times), from uttering this arrant nonsense this week: “I don’t want to be lectured about what we need to do to destroy our economy in the name of climate change.” |

3. Where the politics of climate action go from hereThe Biden administration will have to rely on its less powerful arsenal of executive actions to make progress on its decarbonization efforts, however short of its initial targets. As The Times’s Coral Davenport explains, the White House could use its regulatory authority to increase vehicle emissions standards, potentially catalyzing the transition to electric vehicles; to compel electric utilities to slightly lower their greenhouse emissions without falling afoul of the Supreme Court; and to plug leaks of methane — an extremely potent greenhouse gas — from oil and gas wells. Biden may also use his pulpit to push for action at the state level, where climate policy has assumed new importance in the absence of federal leadership. “States are really critical to helping the country as a whole achieve our climate goals,” Kyle Clark-Sutton of the clean-energy think tank RMI told The Times. “They have a real opportunity to lead. They have been leading.” Both California and New York, for example, have committed to reaching net-zero emissions by no later than 2050. As far as national electoral politics are concerned, The Times’s David Leonhardt argues, the fact that a single Democratic politician was able to derail Biden’s climate agenda should prompt Democrats to redouble their efforts to increase their Senate majority, particularly by winning over more voters in red and purple states. “It is clear that many blue-collar voters don’t feel at home in the Democratic Party — and that their alienation is a major impediment to the U.S. doing more to slow climate change,” he writes. It is also possible that the government’s sclerosis could spur interest in less conventional and extra-electoral avenues to addressing climate change, among them nuclear power (the promise and drawbacks of which have been explored in this newsletter; the “degrowth” movement; speculative technological fixes such as solar geoengineering; and mass movements of civil and uncivil disobedience, as the ecologist Andreas Malm called for in his book How to Blow Up a Pipeline. As the Colorado River reservoirs dry up, as the death toll from the record-setting heat waves and wildfires scorching Europe rises, and as more than a billion people in South Asia recover from a season of heat extreme enough to test the upper limits of human survivability, “this moment feels interminable,” Meyer of The Atlantic writes. “But what is unsustainable cannot be sustained. If one man can block the industrial development of what is, for now, the world’s hegemon, then its hegemony must be very frail indeed.” But then, climate change seems to remain a relatively minor concern among the U.S. electorate: Just 1 percent of voters in a recent New York Times/Siena College poll named it as the most important issue facing the country; even among voters under 30, that figure was 3 percent. That is just one poll. But it would perhaps be premature to rule out another direction the politics of climate change might take, one that could prove familiar to those who have witnessed how the American public has processed other cumulative traumas, like the drug overdose crisis or gun violence or the pandemic: a resigned acceptance of mass suffering, punctuated by moments of shock that serve only as reminders of how the unimaginable became normal. |

3. The impasse at the abyssBokat-Lindell packed many leads and ideas into his closing section. We’ve touched on a lot of them in the past year. Our high points: A. The “arsenal” of potential executive actions is terribly meager vis-a-vis the task at hand. Stronger CAFE standards, for example, are badly undermined by light trucks’ takeover of the automotive fleet, and are assumed in most climate emission scenarios anyway. B. States-as-climate-loci is also overblown. A full two dozen are solidly red, i.e., fossil fuel dominated. Even in blue states, policy is circumscribed by federal authority and bureaucracy; the holdup of New York’s congestion pricing program by federal highway officials is one case in point. Moreover, visions of 2050 net-zero or 2035 grid decarbonization by California and New York are almost certainly way out in front of actual commitments and have been made needlessly more difficult by nuclear power plant shutdowns. C. Securing a true Democratic Senate majority and retaining the House this November are indeed vital.

E. The low primacy of the climate crisis among voters is both real and arguably not fatal. The U.S. is beset by so many crises that even so committed a climate scientist as Peter Gleick declared this week his greater alarm over incipient fascism. A greater cause than insufficient ardor of the U.S. failure to enact “revolutionary” or even strong, incremental climate policies is an unproportionate and cumbersome political system that puts up multiple roadblocks to systemic change. Alas, that isn’t poised to change. More and more, it looks like achieving genuine climate action will require passionate and creative direct action. Targets abound: helicopter commuting, crypto “mining,” obstructionists of wind farms or dense housing or congestion pricing, to name a few. Successful actions will be those that harness broad-based and truly intersectional campaigns attacking not just emissions but privilege and wealth. We have an idea or two up our sleeve. Perhaps you do as well. We wish you luck. We still insist that carbon taxing is revolutionary — how can tackling a fundament of fossil fuel dominance be otherwise? |

New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells, in The Supreme Court’s E.P.A. Decision Is More Gloom Than Doom, July 1.

Justice Elena Kagan, commenting on the 6-to-3 Supreme Court decision in West Virginia v. EPA, quoted in Supreme Court Limits E.P.A.’s Ability to Restrict Power Plant Emissions, by Adam Liptak, in The New York Times, June 30.

Note: This post was amended on July 6 to include @bobinglis’s June 30 tweet, shown below.

Maybe we’re grasping at straws. But we see a possible silver lining in this week’s grievous Supreme Court ruling striking down US EPA’s authority to regulate carbon emissions via the Clean Air Act.

The gleam of hope is not that the decision didn’t dismember the federal government’s entire “administrative state” apparatus — you know, the tapestry of rules, regulations and procedures designed to further societal health, safety and accountability. We fear investigative journalist Amy Westervelt may be right that the ruling is a harbinger of steps in that very direction.

What I’m not seeing a lot of people get is that the West Va v EPA verdict is a harbinger. It’s the first step not the death blow. Overstating it obscures that, leaving people thinking it’s all over and ill-prepared for what comes next.

— Amy Westervelt (@amywestervelt) July 1, 2022

Rather, our thin beam of optimism is the opening the ruling could provide for carbon tax proponents to persuade our fellow climate advocates to lean less on fraught, slow and even quixotic approaches for tackling climate change, and to instead turn increasingly toward carbon taxing as a more-holistic and bulletproof way to bring down stubbornly high carbon emissions, both in the U.S. and worldwide.

In recent years, this space has done battle with what we’ve regarded as inadequate or even illusory climate strategies.

* We’ve criticized the decade-long campaign to divest financial and social institutions from fossil fuels, arguing in our posts and on our evergreen pages that capital will easily find ways to finance whatever legal product consumers demand, especially a product so economically and psychologically fraught as gasoline.

* We’ve hit back at the IMF’s unfortunate labelling of fossil fuels’ vast externality costs — both climate damage and immediate human-health harms — as “subsidies,” for fostering the fantasy that citizens need only stop their governments from bestowing public tax dollars on fossil fuel companies, and Big Carbon will crumble and wither away.

* We’ve even questioned the keep-it-in-the-ground movement, arguing, heretically, that “Oil that doesn’t flow to refineries through the Dakota Access Pipeline [to take one example] will instead come from somewhere else – Kuwait or Texas or a hundred other places – to be burned in cars, trucks and planes.” Our movement’s focus, we’ve argued, must be demand, not supply.

* And we’ve looked long and hard at the climate value of environmental regulation — the very approach the Supreme Court threw under the bus yesterday. Look at how, a year ago, we contrasted the fabulous success of the 1970 Clean Air Act and its 1977 and 1990 amendments in slashing concentrations of particulates and other harmful pollutants in “ambient air,” with the less-technology-amenable issue of carbon emissions:

These and similar successes have led many climate advocates to urge similar regulatory pathways to curb carbon emissions. [Yet] regulatory approaches may offer only modest prospects for controlling and reducing emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, for several reasons. For one thing, the absence of antipollution devices for capturing or lowering CO2 emissions limits the scope of technology-forcing regulation. For another, promulgation of regulations is necessarily piecemeal and reactive. Moreover, the regulation-setting and administering process itself is cumbersome, delay-prone and subject to legal challenge by carbon interests.

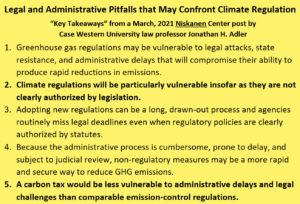

From Niskanen Center post. Link is in text. We’ve added emphasis to #2 and #5.

We backed up that argument with reasoning from a penetrating paper by Case Western University law professor Jonathan Adler. The sidebar at right has Prof. Adler’s own “key takeaways” from the summary version he published on the Niskanen Center’s website. We highlighted two: A, climate regulations that aren’t clearly authorized by legislation will be particularly vulnerable to legal challenges — as we saw this week, when the six right-wing justices took advantage of the absence of explicit mentions of climate or carbon in the Clean Air Act and its amendments. And B, compared to emission-control regulations, a Congressionally enacted carbon tax should be less vulnerable to such challenges.

This isn’t to say that a carbon tax is just around the corner. We readily admit that a path to enacting a meaningful federal carbon tax — not a token, Exxon-style levy that damages coal but not oil or gas, but a robust carbon price that can reach triple digits in a half-dozen or fewer years — is almost impossible to discern.

Rather, now that essentially all of the prominent alternatives have been eviscerated or emasculated, it’s time for climate advocates to rethink, and, hopefully, relinquish, their anti-carbon-pricing positions.

The Carbon Tax Center has strived to be a climate team-player. At least since the start of the Trump administration, we’ve acknowledged the near-impossibility of passing a federal carbon tax in the current political configuration, and have instead pulled for less-ambitious but more-achievable (or so they seemed) incremental steps.

Just last fall, we wrote that “There’s logic in refraining from the one overarching policy that could lead the way to the deep cuts Biden is seeking: an economy-wide carbon tax. Giving businesses and households money to go green [instead] is more palatable, though less potent, than charging them for burning carbon.”

But we’ve also strived to be truth-tellers. That’s why we called that 2021 post, “Without a Carbon Tax, Don’t Count on a 50% Emissions Cut.” And it’s why we’re a little less inclined than some of our climate comrades to go into full mourning over yesterday’s Supreme Court decision .

Supreme Court leaves it up to Congress to act on climate change. That’s OK because Congress can enact a carbon tax and a carbon border adjustment that can make the solution go worldwide. Tax pollution. Un-tax income. Conservatives in Congress, here’s your chance! We need you!

— Former Rep. Bob Inglis (@bobinglis) (R-SC) June 30, 2022

Please also note that unlike the indefatigable Bob Inglis, who bravely fought for carbon pricing as a six-term Member of Congress (1993-1999, 2005-2011) from South Carolina’s 4th District, we’re not calling on “Conservatives in Congress” to push for carbon taxing. We would love it if even a few did, but that ship sailed over a decade ago, as we’ve summarized on CTC’s Conservatives page.

To sum up: Yes, the Supreme Court ruling was ignorant. Yes, it was destructive. Yes, it’s almost certainly a harbinger of worse. But it didn’t demolish policies that were on course to rescue our planet and make Biden a climate hero.

Yesterday’s decision did damage, but maybe it pulled some wool from our eyes as well.

Raymond Zhong, How Extreme Heat Kills, Sickens, Strains and Ages Us, New York Times, June 13.

New York Times climate reporter Henry Fountain, in Climate Change Fuels Heat Wave in India and Pakistan, Scientists Find, May 23.