Could Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s declaration in August that congestion pricing for New York City “is an idea whose time has come” bring needed momentum to carbon taxing?

A strong thread connects congestion pricing and carbon taxes. Just as limited street space in New York warrants a congestion fee, the atmosphere’s limited capacity to absorb carbon necessitates a carbon emissions fee.

Congestion pricing levies fees on vehicle travel into or within the core of a city. Singapore, London and Stockholm have deployed such fees for decades to discourage unnecessary traffic and raise revenue to improve transit and road infrastructure.

Congestion pricing levies fees on vehicle travel into or within the core of a city. Singapore, London and Stockholm have deployed such fees for decades to discourage unnecessary traffic and raise revenue to improve transit and road infrastructure.

I’ve been quantifying the benefits of congestion pricing for New York City city and mobilizing public support for well over a decade. The campaign I’m allied with, called Move NY, proposes tolling car and truck traffic into Manhattan’s central business district, surcharging yellow cabs and Ubers circulating within the CBD, and lowering tolls on outlying bridges that have been used as cash cows to fund transit.

The governor controls the city’s mass transit, and political tradition dictates that congestion pricing legislation must run through Albany. Since Cuomo’s “August surprise” — he rebuffed the idea throughout his tenure as governor — I’ve re-directed my advocacy from carbon taxes to congestion pricing.

That’s a shift in venue but not in philosophy. Both types of fees incentivize all of us who would fire up fossil fuels or occupy road space to do so sparingly. They also help bring forth investment and innovation in alternatives: renewables and efficiency in the case of carbon; transit, cycling and density in the case of urban transport.

A congestion charge for New York will establish in America the foundational principle for a carbon tax: safeguarding our climate and other public goods requires that we charge for uses that damage or deplete it.

Cuomo’s announcement also validates conservative luminary Milton Friedman’s dictum about crises and change:

Only a crisis — actual or perceived — produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.

“Subway meltdown” images like this from NY Times in November have filled the city’s paper this year, putting pressure on Gov. Cuomo to find solutions.

How has the political impossibility of congestion pricing in New York given way to an air of inevitability? As Friedman prescribed, a crisis was required. It came this year, as a twin storm of gridlocked streets and cascading subway delays. But years of concerted advocacy were required to blast through political inertia and lay the crisis at Cuomo’s doorstep.

And true to Friedman’s dictum, NYC advocates for transit and livable streets have developed alternatives: the Move NY plan has dozens of elements that together can unsnarl the streets and modernize transit, as the New York Times reported last month in this profile of the “three amigos” leading the plan: traffic guru “Gridlock” Sam Schwartz, political campaigner (and CTC board chair) Alex Matthiessen, and myself.

We don’t yet know if Cuomo’s congestion proposal, which is expected next month, will be strong medicine or weak tea. But as one long-term advocate said last week, the argument is no longer whether to charge a congestion price, but how much.

The lesson for climate campaigners is clear: our job is to keep building the philosophical and political groundwork for carbon taxing.

That way, when the seeming political impossibility of carbon taxing gives way to the aura of inevitability, the carbon tax that emerges can be robust, comprehensive and fair.

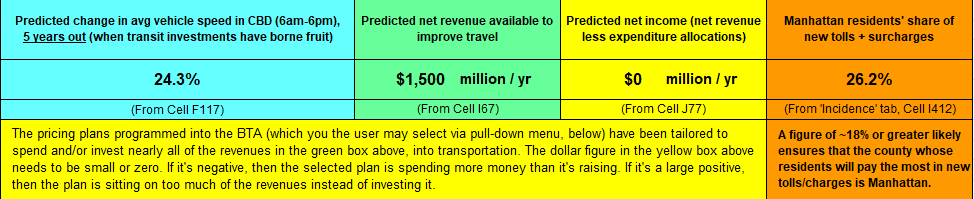

Snapshot from my Excel model shows key projections for the Move NY plan.

In the meantime, if you live or work in New York City or State, voice your support your city and state rep’s and urge them to support the Move NY congestion pricing plan.

Join and work with Move NY’s grassroots partners such as Riders Alliance, Transportation Alternatives, the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance. (More are listed here.)

And don’t stop organizing, teaching and advocating for U.S. carbon taxes.

The trope

The trope  Lifton, a psychiatrist who turned 90 last year, has long observed, lived among and written about the perpetrators and victims of some of the 20th Century’s most profound atrocities — the atomic bombings of Japan, the Vietnam War and, of course, the Nazi Holocaust. His writing humanizing the

Lifton, a psychiatrist who turned 90 last year, has long observed, lived among and written about the perpetrators and victims of some of the 20th Century’s most profound atrocities — the atomic bombings of Japan, the Vietnam War and, of course, the Nazi Holocaust. His writing humanizing the

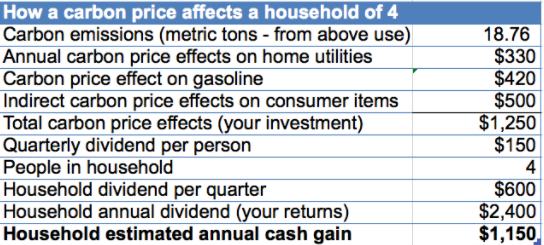

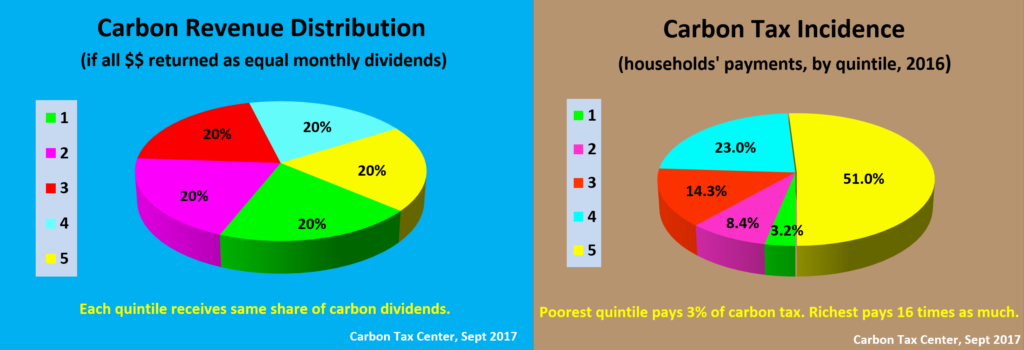

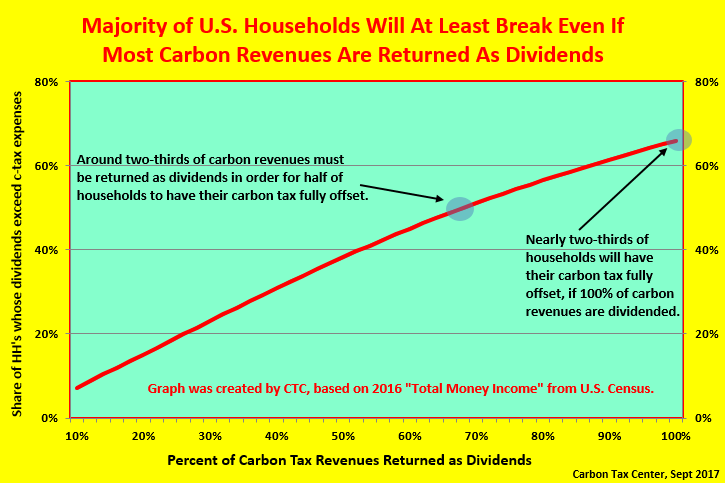

These disparities underlay Bernie Sanders’ “political revolution” campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination last year. And they added fuel to the sense of white grievance that energized Donald Trump’s successful run for the presidency. They also bolster the case for “carbon dividends” — the idea of distributing all or nearly all carbon tax revenues equally to U.S. households popularized as carbon fee and dividend by the non-partisan

These disparities underlay Bernie Sanders’ “political revolution” campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination last year. And they added fuel to the sense of white grievance that energized Donald Trump’s successful run for the presidency. They also bolster the case for “carbon dividends” — the idea of distributing all or nearly all carbon tax revenues equally to U.S. households popularized as carbon fee and dividend by the non-partisan  The progenitors of CLC’s carbon dividend plan, James Baker and George Shultz, are “exemplars of the outcast center-right GOP establishment,” as I described them recently in the

The progenitors of CLC’s carbon dividend plan, James Baker and George Shultz, are “exemplars of the outcast center-right GOP establishment,” as I described them recently in the