[A similar version of this post was published earlier today in Streetsblog.]

If New York State were as diligent as California at preventing emissions tampering by owners of diesel pickup trucks, the resulting health gains could exceed $120 million.

Nationwide, bringing all 50 states up to California’s tampering-prevention level would eliminate around $10 billion in future disease and death costs caused by these gross emitters.

Both figures correspond to tailpipe pollution prevented over the remaining lives of tampered trucks already in use. The savings from thwarting motorists from tampering with new vehicles would be additional.

Read on to see why we’ve paired these images. Navajo Generation Station photo courtesy of Salt River Project. Diesel pickup exhaust photo courtesy of KUTV.com.

These figures denote the economic value of the reduced asthma attacks, worker and student sick days, pulmonary hospitalizations and premature deaths from compelling 80 to 85 percent of owners of “Class 2b or 3” (8,000-14,000 lb) diesel pickups to unplug software “tuners” and after-market engine devices that are causing their vehicles to out-spew unmodified diesel pickup trucks by factors of 30 to 300 for nitrogen oxides and 15 to 40 for particulates, according to an EPA report released last month.

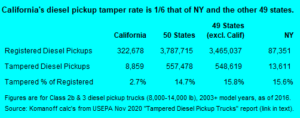

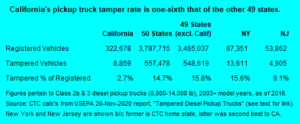

The figures arise from this finding from my Dec. 1 post, “Takeaways from America’s Diesel Pickup Pollution Disaster”: the practice of incapacitating diesel pickup pollution controls to boost “performance” is only one-sixth as widespread in California as it is nationwide: 27 per 1,000 pickups in the Golden State vs. 147 for the country as a whole, 158 per 1,000 for the other 49 states, and 156 per 1,000 in New York State.

Simple ratios tell us that pushing New York’s 15.6-percent tamper rate down to California’s 2.7 percent would cause 11,200 of the state’s 13,600 super-emitter pickups to regain their assembly-line emissions quality.

Calculations based on the EPA report reveal that over its anticipated remaining service life, each modified diesel pickup will blast out more than a ton of extra nitrogen oxide gases (NOx) and nearly 20 pounds of extra particulate matter, compared to an undisturbed vehicle. Each tailpipe hit comes with high costs to our health: around $5 per extra pound of NOx and $40 for PM in New York State, slightly less for the U.S. as a whole.

Calculations based on the EPA report reveal that over its anticipated remaining service life, each modified diesel pickup will blast out more than a ton of extra nitrogen oxide gases (NOx) and nearly 20 pounds of extra particulate matter, compared to an undisturbed vehicle. Each tailpipe hit comes with high costs to our health: around $5 per extra pound of NOx and $40 for PM in New York State, slightly less for the U.S. as a whole.

(I pulled these per-pound costs from a classic workup of the health costs of motor-vehicle-related air pollution: the eponymous 1999 paper by the externality-cost savants Don McCubbin and Mark Delucchi, published in the Journal of Transport Economics and Policy and archived by the London School of Economics. I did some tweaks, inflating the 1991 per-kg costs in the paper’s Table 5 to 2020 dollars, converting from kg to lb, weighting the “US” and “urban” cost rates ¾ and ¼ in New York State but all “US” for the national calculations, averaging “low” and high” costs geometrically rather than arithmetically to temper the highs, and excluding “upstream” and “road dust” costs. And I tacked on an extra 15-20 percent to reflect epidemiologists’ increased understanding in the past two decades of air pollution’s role in strokes, type 2 diabetes, and a range of neonatal diseases related to low birth weight and preterm birth.)

Multiply those dollar rates by the excess emissions in pounds per pickup, and the extra air pollution damages to residents of New York State compute to $11,000 per offending vehicle before it finally hits the scrap heap (more for vehicles driven in NYC and other populated areas, less in, say, the sparse Adirondacks). Ecosystem costs are not included.

Now factor the $11,000 per-vehicle damages by the EPA’s count of 13,600 tampered pickups in New York; the result, $150 million, is the monetary equivalent of the damage they will wreak on New Yorkers’ lives and lungs.

The more salient figure for policy, however, is obtained by applying the $11,000 per-vehicle damages to the 11,200 pickups — five-sixths of the state total — whose emissions would revert to normal if New York instituted anti-tampering policies that matched California’s in efficacy. That figure, around $125 million, denotes the future health damages that New York could eradicate with California-style pursuit of diesel pickup tampering.

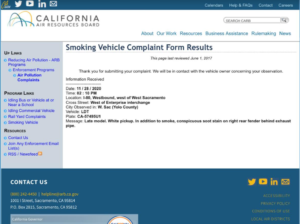

How much would this cost? Probably just a few million dollars a year. Officials at California’s Air Resources Board (CARB), which oversee almost four times as many diesel pickups as New York, told me last week that they run their anti-tampering program on $3 to $4 million a year. Even a decade’s worth of those expenditures by New York State would be more than paid back in the health benefits from the reduced emissions.

What’s the best way for states like New York to get their anti-tampering, clean-air game on?

They could go it alone. But no state has an analogue to CARB, the world’s premier anti-vehicle pollution agency since its founding in 1967. (The link, a CARB web page that informs vehicle owners and dealers which after-market products are legal and which are not, is one among numerous examples of the agency’s problem-solving approach.)

New York’s car and truck inspection system is jointly managed by the Departments of Environmental Conservation and Motor Vehicles. As safer-streets advocates in New York know full well, the DMV habitually ignores entreaties to use its licensing powers to hold habitual dangerous drivers accountable. There’s no reason to believe DMV has the oomph to mount and manage the comprehensive anti-tampering programs that have proven so effective in California. (We asked DMV on Friday why New York’s tampering rate is six times California’s; we’ll add the agency’s response, if we hear back.)

A more productive approach may be for New York to team with other states to follow California’s lead and shut down the aftermarket supply chain of manufacturers, distributors and dealers that sell the emission-control defeat-devices and programs. This effort could be led by state attorneys general like New York’s Letitia James, who have proven to be more pro-active than governors or legislatures and who frequently partner in litigation to protect air and water quality. They could start by suing Amazon to stop the sale of pollution defeat devices.

Now, about our earlier side-by-side pics of a coal-fired power plant and a spewing diesel pickup: a friend of Carbon Tax Center asked us how the “excess” particulate emissions from all tampered U.S. pickups compare with emissions from the coal-fired generating stations in the Grand Canyon airshed. We ran the numbers and found that EPA’s estimate of 5,407 tons of PM over the remaining lives of the tampered vehicles was eerily close to our estimate of 4,900 annual tons from one of the three 750-MW units at the now retired Navajo Generation Station in Page, AZ, 60 air miles from the canyon’s north rim. (We assumed a 75% capacity factor, 99%-effective particulate removal, 15% ash content of the coal, and a 50% average increase in molecular weight from oxidizing the ash in combustion.)

Another way to view that finding is that it takes just 700 or so tampered pickups to produce one megawatt’s worth of particulate emissions from a reasonably well-controlled coal-fired power plant (with the caveat that the pickup pollution is estimated over the vehicles’ expected remaining lives, vs. annual emissions for the power plant).

Rolling coal, indeed! Nevertheless, while monster-truck pro-Trump road rallies may look scary, they’re easy to shrug off. Not so, pulmonary stress from tampered emission controls. California has shown that it’s possible to root out gratuitously dirty diesels. New York and other states should get on it, now.

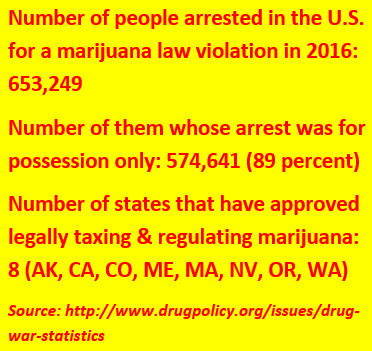

Although you wouldn’t know it, thanks to a near-century of Washington scare tactics, smokeable marijuana is one of the world’s most benign inebriants. As Lynn Zimmer, a sociologist at Queens College, and John P. Morgan, a professor of pharmacology at the City University of New York, showed twenty years ago in “

Although you wouldn’t know it, thanks to a near-century of Washington scare tactics, smokeable marijuana is one of the world’s most benign inebriants. As Lynn Zimmer, a sociologist at Queens College, and John P. Morgan, a professor of pharmacology at the City University of New York, showed twenty years ago in “