Joshua Rothman, “Can Science Fiction Wake Us Up to Our Climate Reality?,” a portrait of Kim Stanley Robinson and his 2020 novel, “The Ministry For The Future,” New Yorker magazine, Jan. 31, 2022 issue.

Since climate progress is stalled, let’s unload on fee-and-dividend

Someone chose an inopportune time to beat up on carbon taxing’s fee-and-dividend variant. Not U-C Santa Barbara political scientist Mitto Mildenberger, whose paper, Limited impacts of carbon tax rebate programmes on public support for carbon pricing, co-authored with scholars from Montreal, Vancouver and Bern (Switzerland), appeared this week in the prestigious journal, Nature Climate Change. No, I mean iconoclast blogger David Roberts, who used Mildenberger’s provocative paper as a launching pad to again dunk on carbon pricing and people who still hold out hope for it.

Roberts’ post, Do dividends make carbon taxes more popular? Apparently not., published on Monday on his Volts platform, gets off on the wrong foot right away, claiming:

Economists have long insisted that pricing carbon is the most efficient way to reduce greenhouse gases. For years, they hijacked the climate discourse, with untold money and effort put behind proposals for various increasingly baroque pricing schemes, to very little effect. (emphasis added)

Roberts may be right about efficiency and economists, but his description doesn’t fit climate hawks like Citizens Climate Lobby and Carbon Tax Center. We place our chips on carbon taxes not on account of their economic efficiency but because of their unrivaled potential to slash carbon emissions quickly in the U.S. — and also their global portability.

The meat of Mildenberger’s paper and Roberts’ post, distilled in their respective titles, is that in the only two countries with some form of fee-and-dividend carbon pricing, not just public support but basic awareness of the programs, particularly the dividends themselves, is middling at best.

We think this “finding” is both questionable and beside the point. Let’s take a close look at each of those countries: Switzerland and Canada.

Switzerland

Official Swiss notice of this year’s carbon dividend. At the current 1.09 exchange rate, 88.20 CHF = $96.14.

Switzerland’s carbon tax began in 2008 and reached its current level of 96 Swiss francs per metric ton in 2018. Converting metrics and currencies, that equates to $95 per ton of CO2, the kind of level that carbon taxers dream about. According to CTC’s carbon tax model, if the U.S. next year started a $15/ton carbon tax and ramped it up to reach $95 in 2030, emissions in that year would be 33% less than in 2005, taking us 2/3 of the way to the Biden target of halving 2005 emissions in 2030.

Not only that, a U.S. carbon tax at the Swiss level of $95 a ton would generate a carbon dividend in 2030 of $1,500 per person, even allowing for reduced emissions and a larger population and equal shares for children. Surely, a $1,500 carbon check — or, if you prefer (and we do) 12 monthly carbon dividends of $125 per person — would translate into strong and rising popularity, especially considering that a majority of people and households would be expending less than those amounts in increased direct and indirect energy costs.

That’s the straw man. The reality is that Switzerland’s $95/ton (U.S.) carbon tax will deliver only $96 in per-person dividends for the entire year. (See document at left, downloadable here.) That’s less than one month’s worth of what U.S. residents would receive under a full fee-and-dividend scheme for a Swiss-level $95 carbon tax. In that light, it should be no surprise that Mildenberger and his co-authors didn’t find residents of Geneva or Zurich dancing in the streets over their carbon dividends. In U.S. terms, Swiss residents’ 2022 carbon tax dividend is what Americans would get in 2030 from a piddling carbon tax of $5.50 per ton of CO2.

Why the discrepancy? Why is Switzerland’s carbon dividend only 1/15 as great as what a U.S. dividend would be from a carbon fee of the same level?

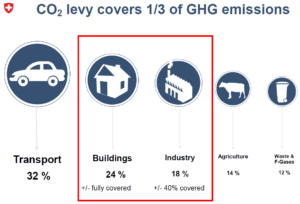

Excerpt from Switzerland Federal Office for the Environment document, “The Swiss Approach to Carbon Pricing,” May 2021.

There are four big reasons. First, Switzerland’s energy consumption is far less per capita than that of the United States. Second, hydro-electricity rather than carbon-based fuels like coal and methane powers the country’s grid. Third, the Swiss carbon tax exempts transport and agriculture and more than half of Swiss industry (see graphic at right; full document here). Fourth, part of the tax revenue is siphoned off by businesses before the dividends get calculated.

No wonder, then, that Switzerland’s carbon dividend is so meager. Consider further that, as Mildenberger et al. point out, “Citizens receive their rebates as a discount on their health insurance premiums, with annual notifications about this monthly benefit through health insurance forms.”

Annual notifications through health insurance forms. This is reasonable, even enlightened, public policy. It’s also almost diabolically designed to obfuscate the dividend side of the carbon fee coin.

Canada

Canada’s carbon tax is far more complicated than Switzerland’s. When we last updated CTC’s Canada page, in March 2011, we characterized carbon pricing in the country’s 13 provinces as follows:

- Six provinces, including Ontario and Alberta, were covered by the federal pricing scheme that would reach $50/tonne in 2023 — around $36/ton in U.S. terms — and then ramp up sharply to $170/tonne by 2030.

- Four were deploying their own carbon tax, led by British Columbia, which inaugurated the Western Hemisphere’s first meaningful carbon tax in 2008.

- Quebec and Nova Scotia were part of a two-country carbon cap-and-trade program that is anchored by California.

- New Brunswick employed an output-based carbon pricing system.

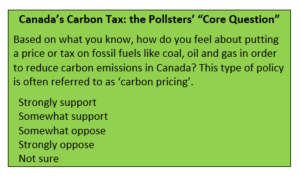

Wording courtesy of UCSB Prof. Matto Mildenberger, lead author of the Nature Climate Journal article discussed here.

Given this patch-quilt, as well as the novelty of carbon pricing in most of Canada, it seems to us unsurprising that polling that commenced in February 2019 (and extended through May 2020, with five “waves” in all) would yield the mixed results reported in the Midenberger paper: upticks in two provinces, Ontario and British Columbia, and downturns in the other three, Quebec, Alberta and Saskatchewan.

The “core question” asked in the Canada polling, as described by lead author Mildenberger, who graciously shared it with us yesterday via email, is shown at left. The language is neutral, perhaps to a fault. It offered no affirmative spin, such as “Canada recently began taxing fossil fuels in order to protect the climate, with the money rebated in ways that will help households get ahead financially.” That kind of favorable tilt could perhaps be justified as necessary to counter the negative vibe surrounding taxation generally.

To be sure, that negative vibe is precisely what drives pundits like Roberts to deride carbon taxing, as he did in the second and third paragraphs of his post:

Over time, political experience with carbon taxes has highlighted a truth that should have been obvious long ago: carbon taxes are taxes, and people don’t like taxes. People don’t like paying more money for stuff.

More broadly, carbon taxes are an almost perfectly terrible policy from the perspective of political economy. They make costs visible to everyone, while the benefits are diffuse and indirect. They create many enemies, but have almost no support outside the climate movement itself. All the political intensity is with opponents.

We get it. We know full well the albatross that taxation always bears. But we also know that taxes on “bads” have been enacted into law. The U.S. government taxes cigarettes, as does every state. New York City taxes grocery bags, and Philadelphia and Berkeley, CA tax sugary soft drinks.

Obviously, taxing something as supercharged financially and culturally as fossil fuels is a much heavier lift, as evidenced by the absence of explicit carbon taxing anywhere in the fifty states. (We exclude federal and state motor fuel taxes, due to their tie-in to roads rather than health or climate; we also exclude New York State’s Petroleum Business Tax, though its support of NYC metro-area transit perhaps merits an honorable mention; conversely, New York City’s congestion pricing program, now scheduled to begin in 2023, will create a strong template for carbon taxing, as we’ve pointed out many times, including in The Nation magazine in 2019.)

So yes, carbon taxing — not fig-leaf $20/ton-and-no-higher carbon taxing a la Exxon or the occasional Republican, but a levy rising steadily to triple digits before 2030 — is hard stuff. But so is just about every other decarbonization policy or program, especially if done at scale.

Well-heeled NIMBY’s have whittled down wind projects for years; now, so too may supply-chain problems. Rooftop solar endures pushback not just from utilities and their high-wage unions but also from concerns that lower-income residents could gett stuck with higher utility bills. Only splinters of President Biden’s Build Back Better plan, which wasn’t going to be able to deliver its promised 50% cut in emission by 2030 anyway, will pass, thanks to one or two Democratic senators and 50 Republicans. Even the push to electrify everything may find its vaunted carbon benefits a good deal less potent than advocates imagine, an issue we intend to explore in a future post.

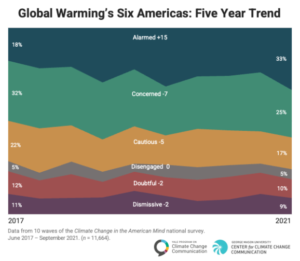

A record one-third of Americans in the latest “Global Warming’s Six Americas” are “alarmed” by climate change.

Still, though, the biggest misdirection in the Mildenberger et al. paper and the Roberts post may be their fretting over public opinion in the first place. The public doesn’t have to love carbon fee-and-dividend. It simply needs to embolden political leadership that will enact it (and the raft of complementary policies) into law and ensure that the fee, which shouldn’t be set too high to start, can keep rising over time.

Public opinion increasingly supports climate action, not tepidly but “with alarm,” as the latest Yale – George Mason opinion survey of “Global Warming’s Six Americas” attests (see graphic at right, and more detailed treatment with link here). It’s past time for carbon pricing naysayers to throw off their ideological blinders and get behind policies that can pass and deliver.

PS to David Roberts: Contrary to your Volts post, fee-and-dividend did not “los[e] badly in a public referendum in 2016.” What went down to defeat in Washington state was a sales tax swap of the carbon revenues, necessitated by the state’s constitutional prohibition against dividend-type state tax treatments. And what doomed the proposal was opposition from climate hawks who took umbrage at being leapfrogged politically, and in revenge brought in lefty heavy hitters to slime the measure. But that’s another story.

Huge hat tip to friend of CTC Drew Keeling for Swiss materials and perspective. Drew’s most recent Carbon Tax Center post, Rural disgruntlement, pro-climate complacency sink expansion of Swiss carbon tax, appeared in June 2021.

Breaking a long-standing national temperature record is hard (Canada’s old high-temperature record dated to 1937); surpassing it by eight degrees Fahrenheit is, in theory, statistically impossible. It was hotter in Canada that day [Tuesday, June 29, 2020] than on any day ever recorded in Florida, or in Europe, or in South America.”

The Year in Climate: A summer that really scared scientists, by Bill McKibben, The New Yorker, Dec. 16.

We are in a climate crisis. There is no room for the left hand and the right hand to be doing different things. It’s not credible to say you’re fighting for 1.5 degrees while you’re calling for increased oil production.”

Jennifer Morgan, executive director, Greenpeace International, reacting to President Biden’s appeal to OPEC countries to pump more oil, in Even as Biden Pushes Clean Energy, He Seeks More Oil Production, New York Times, Nov. 2.

Pretty wild to see people imply there’s going to be a “next time” for climate legislation. I mean, sure, you can technically pass a climate bill whenever. 2100, even. But I think the nature of the problem has eluded you.”

New Republic contributing editor Osita Nwanevu, via Twitter, Oct. 27.

Why the Carbon Tax Center Questions the Latest Carbon Tax Talk

Our post last Friday about Build Back Better was already pushing the boundaries by contending that the Biden infra plan won’t actually cut CO2 50% by 2030, when we added this at the end:

We suspect that even a starter, “proof of concept” carbon tax at this time will prove to be a poor idea. Passing a carbon tax in lieu of aggressively raising taxes on high income and instituting taxes on great wealth, as several Senate Democratic climate hawks floated today, amounts to budget-balancing on the backs of both the working poor and the beleaguered middle class. It’s inequitable and a terrible template for the really large carbon taxes that progressive Democrats must eventually enact, in the event they ever reach centrist-proof majorities.

But wait: CTC is supposed to be supporting efforts to pass a U.S. carbon tax. Why, then, were we throwing darts at the Senate Democrats’ trial balloon that was aimed at doing just that?

We have four reasons:

- We don’t think Congress can pass a carbon tax in 2021 anyway.

- We believe the carbon tax under discussion won’t offer sufficient protection to ordinary Americans.

- We doubt that any carbon tax under discussion can generate big enough emission cuts.

- We fear that Democratic backing for a carbon tax at this time will make it harder to defeat the climate-denying G.O.P. in the 2022 midterms.

Things were moving fast last Friday afternoon and we weren’t able to polish our remarks. Now, with a bit more time, let’s unpack these points.

1. Congress can’t pass a carbon tax in 2021 anyway.

The make-or-break Senate votes aren’t there. Manchin of West Virginia won’t vote for a carbon tax, Sinema of Arizona can’t be counted on, and it wouldn’t be surprising if a few Senate or House Democrats facing tough re-elections defected as well. And no Republicans will come on board. Carbon-tax proponents and other climate hawks have waited in vain for over a decade for a single sitting Republican member of the Senate to stand up for strong climate action just once. There’s no reason to think our prayers are about to be answered.

2. The carbon tax under discussion won’t protect enough ordinary Americans.

President Biden has pledged not to raise taxes on Americans earning less than $400,000 a year. A straight-up fee-and-dividend, which is the type of carbon tax CTC most strongly favors, would violate that en masse, despite being strongly income-progressive.. The reason: most six-figure households are high-carbon consumers and thus would be carbon-taxed more than they would be dividended.

If you’re unsure about that, consider the main finding of Anders Fremsted and Mark Paul’s superb 2017 paper for U-Mass’s Political Economy Research Institute, A Short-Run Distributional Analysis of a Carbon Tax in the United States: While 84 percent of households in the bottom income half would be made better off with carbon dividends, only 55 percent of all households would be beneficiaries. Simple arithmetic on those two propositions indicates that only 26 percent of the more affluent households would benefit. (The calculation: 84% of the bottom half equals 42% of all households. The remaining 13 percentage points of beneficiaries constitute just 13%/50%, or 26%, of the top half.) The optics of squaring such a carbon tax or fee with the pledge aren’t promising.

(If Fremsted and Paul’s finding seems too pessimistic, consider this alternative scenario: if 90 percent of bottom-half households were posited as better off, and same for 65 percent of all households, then the share of upper-half households being made better off would come to 40 percent — higher than the 26 percent above, but still a minority of that group.)

To be clear, CTC has no qualms about raising taxes on the very-affluent as well as the super-rich to make a better society. But raising taxes on the working poor and the beleaguered middle class is another matter entirely. And to the extent that the carbon tax under discussion is meant as a pay-for — literally, to pay for improving America’s physical and social infrastructure — less money will be available for dividends. It’s one thing to set aside a few percent of carbon fee revenues to pay for worker and community transitions, as outspoken climate hawk Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) proposed this summer; but it’s another thing altogether to set aside, say, 25 percent for pay-for’s. Having only 75 percent of carbon revenues available for dividends will consign millions of non-affluent households to paying more for energy and energy-intensive goods than they receive as dividends.

To be clear, CTC has no qualms about raising taxes on the very-affluent as well as the super-rich to make a better society. But raising taxes on the working poor and the beleaguered middle class is another matter entirely. And to the extent that the carbon tax under discussion is meant as a pay-for — literally, to pay for improving America’s physical and social infrastructure — less money will be available for dividends. It’s one thing to set aside a few percent of carbon fee revenues to pay for worker and community transitions, as outspoken climate hawk Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) proposed this summer; but it’s another thing altogether to set aside, say, 25 percent for pay-for’s. Having only 75 percent of carbon revenues available for dividends will consign millions of non-affluent households to paying more for energy and energy-intensive goods than they receive as dividends.

3. The carbon tax under discussion won’t generate big emission cuts.

This objection is somewhat speculative because, perhaps understandably, no Senate Democrat has yet attached a level to their carbon tax trial-balloon. But there’s a tendency to overstate what a modestly-sized carbon tax can accomplish.

For example, Resources for the Future, the influential environmental think-tank cited in last Friday’s New York Times story that touched off the latest carbon tax discussion, projects that a carbon tax that starts in 2023 at $15 per metric ton, rises slowly to $30 in 2028 and then jumps to $50 in 2030, will cut CO2 emissions in that year by 44 percent from 2005 levels. That would represent an 1,850 megatonne drop in emissions from 2019. But plugged into our carbon tax model, those inputs yield only a 775 megatonne drop, or much less than half as much. To be sure, RFF’s modeling also includes a clean electricity standard (a close cousin of the Clean Electricity Performance Program in the Biden package that we discussed in our earlier post), but the CEPP would be partly duplicated by the carbon tax and thus wouldn’t account for the bulk of the difference between our respective model results.

Would we support the more modest RFF carbon tax nonetheless if it could be guaranteed to be economically progressive in the aggregate? You bet we would. Our concern on this score is what we telegraphed in our Sept 27 post: the need to neutralize undeserved hype being vested in any climate policies, including carbon taxes.

4. Democratic backing for a carbon tax now will make it harder to defeat the climate-denying G.O.P. in the 2022 midterms.

We won’t belabor this point. Too much depends on the Democrats’ retaining full control of Congress in next year’s midterms and having a good shot at holding on to the White House in 2024. We believe a lot more organizing, educating and communicating about the power, fairness and benefits of carbon taxes remains to be done before the party is somewhat safely inoculated against the inevitable blowback against even an economically progressive carbon tax. Much of that effort will need to go into bringing environmental justice and other progressive activists into the fold.

What kind of carbon tax does the Carbon Tax Center want?

CTC wants a carbon tax that can pass, that’s certifiably progressive (economically), that is robust enough in its per-ton rate to be able to help eliminate game-changing amounts of CO2 and fossil fuels, and that won’t cause gross damage to the Democratic Party’s brand and thus make it easier for the Trumpian right to regain power.

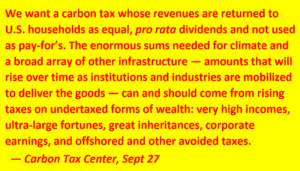

Translated: We want a fee-and-dividend carbon tax, i.e., a carbon fee whose revenues are returned to U.S. households as equal, pro rata dividends and not used as pay-for’s. The enormous sums needed for climate and a broad array of other infrastructure — amounts that will rise over time as institutions and industries are mobilized to deliver the goods — can and should come from rising taxes on undertaxed forms of wealth: very high incomes, ultra-large fortunes, great inheritances, corporate earnings, and offshored and other avoided taxes.

This structure will let the carbon tax rise steadily over time and perform the function it does best: instill the price incentives and social signals to steer U.S. households, businesses, habits and norms away from fossil fuels and into the broad array of alternatives — everything from bicycles and denser living patterns to wind turbines and solar roofs — that won’t heat our climate beyond repair.

Without a Carbon Tax, Don’t Count on a 50% Emissions Cut

Since April, when President Biden committed the United States to sweeping cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, climate advocates have tried to figure out how he could fulfill his goal of a 50 percent reduction from 2005 levels by 2030.

Their talk is not of a government-led Green New Deal — too hot for a skittish Congress — but of a tapestry of GND-ish policies, many of them wonky. Heading the list are schemes to shovel government cash to utilities that shut down coal- and gas-fired power plants, and to motorists who go electric.

The 37% reduction we estimate for Biden’s Build Back Better package would be a major achievement. 50% will require a robust carbon tax.

There’s sense in these and the other policy pieces, just as there’s logic in refraining from the one overarching policy that could lead the way to the deep cuts Biden is seeking: an economy-wide carbon tax. Giving businesses and households money to go green is more palatable, though less potent, than charging them for burning carbon.

But it’s fair —imperative, actually — to ask if the numerical cuts being attached to those programs actually add up to 50 percent. We don’t think they do; the hill is too steep. Compared to pre-pandemic (2019) carbon emissions, Biden’s goal entails a massive cut, 42 percent, in under a dozen years.

Decarbonizing on that kind of scale falls outside the bounds of the possible without a stiff carbon emissions price. Our purpose here is to show why, and also point a way around.

1.

To kick off this discussion, consider Robinson Meyer’s June 2021 Atlantic article, A “green vortex” is saving America’s climate future. Its big idea was that “decarbonization by doing” — deploying more electric cars and more grid storage systems and more solar panels — is driving down these low-carbon technologies’ costs, naturally leading to more deployment and increasingly kicking fossil-fueled cars and power plants to the curb.

It’s an attractive if familiar notion, this “green vortex.” Sit back, let green energy grow cheaper and bigger, and watch carbon emitters fade to black. But Meyer overhypes it. After outlining the high points of U.S. carbon reductions over the past decade, he states:

Under America’s new Paris Agreement pledge, the country will need to double the pace of its emissions decline over the next decade. Whatever we’re doing right, we’re soon going to have to do it twice as fast. So we’d better figure out what it is. (emphasis added)

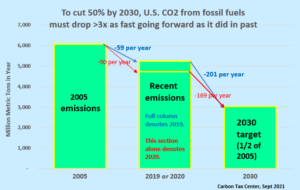

We posed these questions to Meyer, after running calculations on U.S. CO2 emissions from fossil fuel burning. By our count, which is fully detailed in our carbon-tax spreadsheet (see link, three paragraphs below), those emissions totaled 6,070 megatonnes (million metric tons) in 2005 and 5,250 megatonnes in 2019. That computes to 60 fewer megatonnes each year. The task ahead — dropping another 2,215 megatonnes to slim down to 3,035 (half of the 6,070 benchmark) — requires that from 2019 to 2030 we purge 200 megatonnes each year —3.4 times the annual rate of shrinkage from 2005 to 2019.

Extrapolating from 2020 emissions makes the 2030 target look achievable. We don’t recommend it.

In Meyer’s telling, thanks to the green vortex we’ll manage to double our established pace of decarbonization. He might be right. But what if doubling our average annual decline in emissions from 2005-2019 won’t fulfill Biden’s pledged 50 percent cut by 2030? What if it only yields a 35 percent reduction from 2005 emissions, the standard benchmark? What if cutting emissions 50 percent requires that from now to 2030 future U.S. emissions must come down three to four times faster than they did in 2005-2019?

(Perhaps Meyer, who didn’t reply to our email, used 2020 rather than 2019 as his goalpost. That would give him his “doubling,” but meaninglessly. A year that completely upended energy commerce — in which U.S. air travel fell by a third, for example — might be defensible as a new goal post, but not as a basis for computing a new downward trend.)

2.

To grasp how hard it will be for the Biden administration to bend the emissions curve sharply downward without a carbon tax, let’s look at key sectors. A good tool for that is the national carbon-calculator spreadsheet maintained by the Carbon Tax Center (downloadable 3 MB xls).

The Biden plan’s centerpiece is an idea that has become a darling of climate hawks, the Clean Electricity Performance Program. It’s a $150 billion scheme to decarbonize U.S. electricity generation by paying utility companies to replace coal- and gas-fired plants with carbon-free power from wind, solar, biomass or nuclear sources.

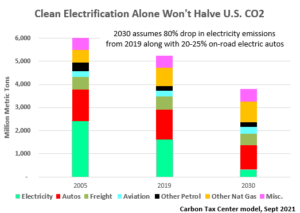

Just over 30 percent of U.S. carbon emissions came from the power sector in 2019, down from 40 percent in 2005, a noteworthy drop that accounted for most of the reductions that Meyer touted in The Atlantic. Let’s assume, as do the White House and its climate allies, that the CEPP’s cash incentives leverage falling prices of solar and wind electricity to achieve the canonical goal of eliminating 80 percent of 2019 power sector carbon emissions by 2030.

The complementary, longer-standing climate policy cornerstone, to “electrify everything,” rests on the eminently reasonable premise that decarbonizing electricity is simpler than mass-producing low-carbon versions of gasoline, natural gas and other carbon fuels. Our calculations optimistically accelerate the uptake of electrified transportation by five years by having the electric shares of cars, trucks and planes in use in 2030 reach levels that in our opinion otherwise aren’t likely until 2035: 20-25 percent for autos, 11-12 percent for trucks and 4 percent for airliners. Those shares are pretty aggressive for 2030, considering that vehicle fleets turn over relatively slowly.

The carbon reductions from this scenario are creditable. With electricity 80% decarbonized and electric vehicles advanced by five years, U.S. CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels would be 35 to 40 percent less in 2030 than they were in 2005. The reduction, more than two million metric tons of CO2 a year, would qualify as by far the greatest extinction of carbon pollution in history.

But why isn’t the reduction 50 percent? Reason #1 is ever-burgeoning travel. Unless policy interventions like road pricing, public transit and density-friendly upzoning can take root on a grand scale — unlikely in just a decade — the emission reductions from hastening electric transportation will largely be offset by more travel, especially as vehicles on our roads grow ever bigger and more power-demanding.[1]

To be sure, our calculations omit other wonky but potentially potent forms of decarbonization such as widespread replacement of gas furnaces by electric heat pumps. Nor do they incorporate low-hanging fruit from reducing the number two greenhouse gas, methane, both via process capture and as a concomitant to phasing out this fossil fuel altogether.

But we should also be mindful that our most crucial assumption — that we’ll double electricity generation’s carbon-free share from 40 percent today to 80 percent by 2030 — is far from assured. Assume that our aspirational 80 percent carbon-free 2030 electricity comes as 24 percent solar photovoltaics, 32 percent wind, and 24 percent combined from nuclear, hydro-electricity and biomass.[2] Getting to 24 percent solar demands that between now and 2030 we install solar cells three-and-a-half times as fast as we have in any three-month period to date,[3] a task that could easily be sidelined by any number of issues involving supply bottlenecks, permits and certifications.

And if that’s not daunting enough, consider that for wind power to contribute its assigned 32 percent, we’ll need to add the equivalent of 75,000 giant wind turbines rated at 5 MW each[4] to America’s landscapes. Numerically, that equates to 25 turbines per county in the U.S. — a formidable task even if America’s NIMBY culture could somehow be conquered. And all of these targets will be even larger if, as seems likely, the CEPP holds down electricity prices, neutralizing what would otherwise be a helpful brake on demand for power.

3.

Since April, we’ve combed policy papers and journalism about fossil fuel emissions for an accounting of cuts that together might meet the Biden 50% target, or at least come close.

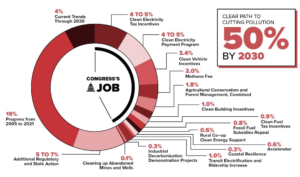

The best compilation we found is a policy brief signed by 20 mainstream and environmental justice organizations and released earlier this month by the Center for American Progress.[5] It’s crisp and precise, as is the Sept. 17 write-up, In the Democrats’ Budget Package, a Billion Tons of Carbon Cuts at Stake, by Inside Climate News journalist Marianne Lavelle, that linked to it.

Graphic, courtesy of Center for American Progress. Link in text.

The above graphic from the CAP brief (downloadable pdf) gives a good overview. Since it’s a lot to take in, we’ve broken it into three pieces.

- Fourteen policies included in Biden’s Build Back Better Act, summing to reductions of 22%. We’ve already covered the three largest, pertaining to clean electricity and electric vehicles. They sum to a 22% reduction from 2005 emissions. We haven’t checked the individual numbers, but the overall figure appears solid.

- “Additional Regulatory and State Action,” assigned a reduction range of 5%-7%.

- Two ongoing trends summing to reductions of 23%. The item at far left, 19%: Progress from 2005 to 2021, is supposed to denote the fall in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions from the 2005 baseline. The companion entry at the top, 4%: Current Trends Through 2030, applies forward from 2021. Together, these items purport to deliver large emission reductions without any new policies — along the lines of Rob Meyer’s “green vortex.”

The percentages credited to the three pieces would indeed carry the Biden plan across the 50 percent reduction threshold. But item #2, unspecified regulatory and state action, is vague and squishy. Worse, #3, “ongoing trends,” is numerically questionable. The CAP policy brief projects that 2030 emissions will be 23 percent below 2005 levels with no further policy actions (known as “business as usual”). Yet our modeling says that 2030 business-as-usual emissions will be just 13 percent under 2005 — a 10 point difference from CAP.

That’s no petty discrepancy. It’s also hard to parse in a blog setting. In addition, we don’t know how CAP and its partners derived their figures (ours are shown in the carbon-calculator spreadsheet we linked to earlier). All the same, here are our hunches as to why CAP’s forecasted emissions trajectory is much lower than ours:

- Like Meyer in The Atlantic, CAP could be projecting future emissions from pandemic-depressed 2020 emission levels. In contrast, we think this year and next will bring big rebounds.

- CAP may not be accounting for “natural” emissions growth accompanying increased economic activity. Our modeling of business-as-usual emissions has 2030 matching 2019, as decarbonization of electricity is offset by emissions caused by increased travel and industrial activity.

- CAP’s figures cover all greenhouse gases, including methane, forest sequestration of carbon, and other activities, whereas ours only cover carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels, which tend to be less amenable to change.

Our takeaway is that CAP and its partners are straining to be able to validate the ambition in Biden’s Build Back Better Act to cut emissions by 50 percent.

As noted earlier, a 35-40 percent cut from 2005 to 2030 would still be praiseworthy, even monumental. We would take it in a heartbeat, given the parlous state of American politics and governance. Nevertheless, we ought to be candid about what our policy tools can, and can’t, accomplish.

4.

From @carbontaxcenter, Sept 24.

The point of this post isn’t to weaken support for the Biden package. Monumental cuts are absolutely worth legislating. Nor are we seeking to beat the drum for a carbon tax at this juncture. As CTC has stated repeatedly this year, as early as in this April 2 post, the kind of carbon tax needed to embellish those cuts can’t possibly pass Congress in 2021.

We also suspect that even a starter, “proof of concept” carbon tax at this time will prove to be a poor idea. Passing a carbon tax in lieu of aggressively raising taxes on high income and instituting taxes on great wealth, as several Senate Democratic climate hawks floated today, amounts to budget-balancing on the backs of both the working poor and the beleaguered middle class. It’s inequitable and a terrible template for the really large carbon taxes that progressive Democrats must eventually enact, in the event they ever reach centrist-proof majorities.

Rather, our intent is to try to neutralize the unattainable hype around Build Back Better or other laudable efforts that can’t or don’t include robust carbon pricing.

In case you’re curious, however — we certainly were — we ran our model numbers to see how big a carbon tax would be needed to meet the Biden goal and cut 2005 U.S. CO2 emissions by 50 percent in 2030. Here’s our answer: combined with the CEPP or other measures to ensure 80% decarbonization of electricity (vis-a-vis 2019), along with the same 5-year acceleration of electric cars, trucks and planes we assumed earlier, an economy-wide carbon tax taking effect on Jan. 1, 2022 at a level of $20 per ton (short, not metric) of CO2 and rising each year at $15/ton to reach $140/ton in 2030, would do the trick.

Addendum, Sept 27: Our brand-new follow-on post, Why the Carbon Tax Center Questions the Latest Carbon Tax Talk, elaborates on our critique of the current carbon-tax trial balloon discussed directly above.

[1] Compared to 2005, CO2 emissions in 2030 in this scenario will have fallen by only 23 percent for cars and 9 percent for trucks while increasing by 18 percent for planes, even with accelerated electrification. Another factor holding back emissions progress is increased use of natural gas, as cheap fracked gas finds abundant uses in industry and heating.

[2] The 24 percent combined electricity share for nuclear, hydro and biomass assumes that 2030 generation from those sources remains at current levels. (Their share shrinks slightly because total electricity production rises somewhat; see next footnote.)

[3] Our modeling projects that without a carbon tax, U.S. electricity generation will rise from 4,160 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2019 to 4,800 TWh in 2030, with around a fourth of the increase attributable to electrified transport. Solar’s 24% share of that, 1,153 GWh, requires nearly 900 GW of installed solar capacity, assuming that a GW of solar produces around 1.3 TWh of electricity in a year, for an average capacity factor of 15%. From several sources, including this recent report by the Solar Energy Industries Association, U.S. installed solar at the end of 2020 was around 100 GW. To grow to 900 GW by the end of 2030, the U.S. solar sector would have to add 800 GW over 10 years, or 80 GW a year. From this report by Wood-McKenzie, the U.S. installed 5.7 GW in 1Q 2021 — a 1Q record — which implies an annual rate of 23 GW.

[4] Assuming an average capacity factor of 35%, wind power’s assumed 32% share of U.S. 2030 generation, 1,537 TWh, requires 500 GW of installed capacity, for a roughly 380 GW increment over end-of-2020 capacity of 122 GW, per U.S. DOE. We optimistically assume an average new-turbine size of 5 MW, although an Internet check on Sept 16, 2021 suggests that the U.S. has no operating wind turbine as large as 5 megawatts (see Windpower Monthly’s Ten of the Biggest Turbines). The U.S. has 3,006 counties.

[5] “The Climate Test: The Build Back Better Act Must Put Us on a clear path to cutting climate pollution 50% by 2030.” Statement, “20 Groups Call on Congress To Pass the ‘Climate Test.’” 4-page policy brief (pdf).

“The penalty on pollution is really important. All the analyses show that you get big reductions in carbon emissions if you have a penalty on polluting. Take that away, and all you have is another government subsidy for renewable energy.”

Harvard prof. and former Obama advisor Joseph Aldy, on Sen. Joe Manchin’s bid to remove penalties for utilities that fail to rapidly phase out carbon electricity from Pres. Biden’s proposed Clean Electricity Performance Program, in NY Times, This Powerful Democrat Linked to Fossil Fuels Will Craft the U.S. Climate Plan, Sept. 19.

It looks like in 1945. But this is a war without bombs. Nature is hitting back.”

Günter Prybyla, 86, who during World War II spent five days buried under rubble in a bombed-out basement when he was 8 years old. — NY Times, Katrin Bennhold, After Deadly Floods, a German Village Rethinks Its Relationship to Nature, August 6.

Malm’s more tantalizing project, because politically it is more feasible, is for saboteurs to strike at the absurd, obscene carbon gorging of elites – to disrupt unnecessary luxury demand that could be cut off with no pain to people who already have too much.

Christopher Ketcham, in his CTC post, Let’s Blow Up Luxury Carbon, concerning Andreas Malm’s book, “How to Blow Up a Pipeline,” July 22.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- …

- 170

- Next Page »