The New York City public affairs site Gotham Gazette today published my essay, For Long-Term MTA Funding, Look to a State Carbon Tax. I’ve cross-posted it here to allow comments and to bring it directly to the Carbon Tax Center’s readership.

— C.K., May 4, 2023

That huge sigh of relief from New York City mass transit advocates last weekend was for the state budget handshake to tack more than a billion additional dollars a year onto a key MTA funding stream, the Payroll Mobility Tax. According to both my calculations and an announcement from Gov. Kathy Hochul, the agreed-to 75% rise in the tax rate on employee salaries paid by businesses in the five boroughs will add $1.1 billion to the PMT’s ongoing annual $1.8 billion take.

That huge sigh of relief from New York City mass transit advocates last weekend was for the state budget handshake to tack more than a billion additional dollars a year onto a key MTA funding stream, the Payroll Mobility Tax. According to both my calculations and an announcement from Gov. Kathy Hochul, the agreed-to 75% rise in the tax rate on employee salaries paid by businesses in the five boroughs will add $1.1 billion to the PMT’s ongoing annual $1.8 billion take.

(The numbers prorate imperfectly because the rise in the tax rate, to 60/100 of one percent, applies only in the city; the rate in the seven suburban MTA counties remains 34/100 of one percent.)

The upward bump in the PMT is part of the package to avert a fare hike and service cuts that would have jolted the entire metro region. Raising the same $1.1 billion via the subway farebox, for example, would have required a whopping 35% jump in fares, a calamity that would have triggered enough new car, cab, and Uber trips to slow vehicles in Manhattan by 5% and boosted city and regional carbon emissions by nearly 400,000 tons of CO2 a year — enough to negate the climate benefit of 90 new large wind turbines, according to my modeling. And these figures don’t include lost jobs and commerce from worsened transportation. Reducing service to save the same amount would have produced similar bad outcomes.

Score a big win, then, for transit and New York. But the new revenue comes with a downside: taxes on payrolls discourage hiring and compound our area’s anti-business aura. Moreover, this revenue infusion will almost certainly be not the last but the first in a series the MTA will require throughout the decade to limit future fare hikes and improve service even as ridership continues to lag pre-pandemic volumes. Counting on raising the PMT next time, and the time after that, will be a fool’s errand. There has to be a better way.

I believe there is: enact a modest statewide carbon tax and dedicate a third to a half of the revenue to shoring up public transportation budgets around the state, though principally in New York City.

Reappraising Carbon Taxes

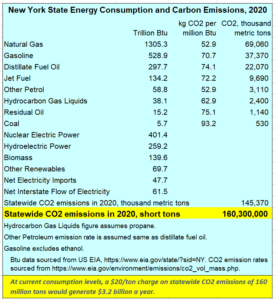

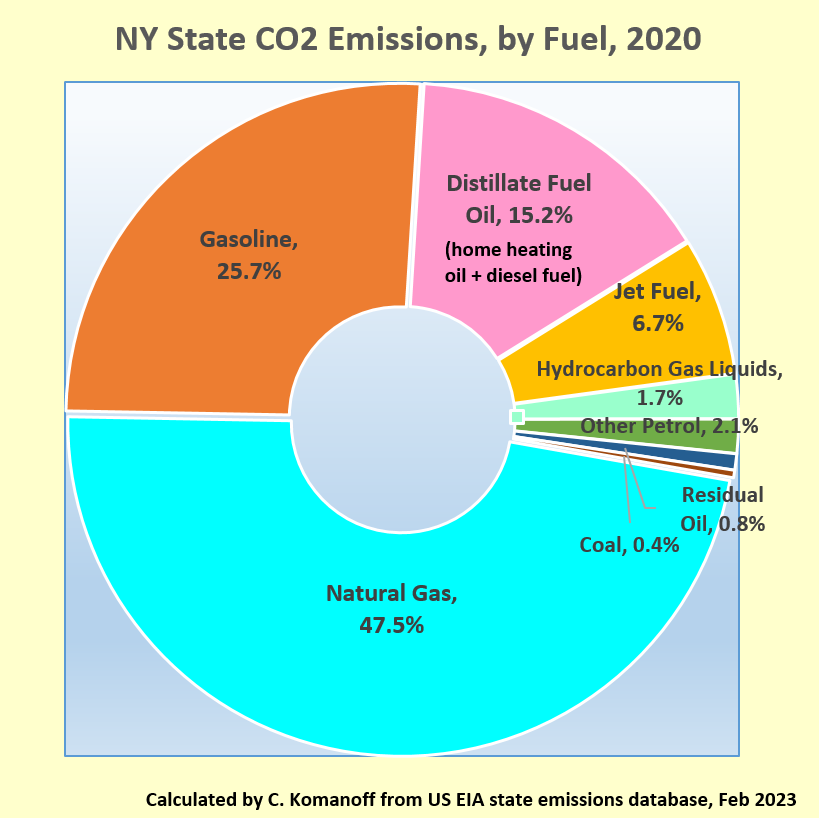

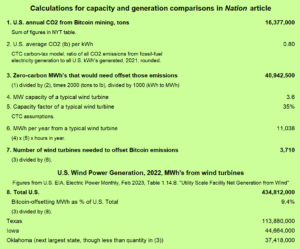

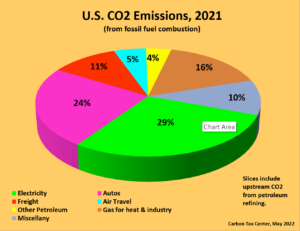

On January 1, Washington state launched its carbon-pricing program, the nation’s second all-sectors carbon charge, with a starting price around $20 per ton of CO2, though most of the emission allowances fetched even higher prices in the first carbon auction, in March. I estimate that the same $20 price applied to all fossil fuels burned in New York State could generate revenues of $3 billion a year (see table).

Dedicating a third of those proceeds to the MTA would add a billion dollars to the authority’s annual revenue. Other slices of the revenue could cure deficits at smaller transit systems around the state.

Dedicating a third of those proceeds to the MTA would add a billion dollars to the authority’s annual revenue. Other slices of the revenue could cure deficits at smaller transit systems around the state.

Even with these allocations, roughly half of the new $3 billion in annual carbon revenues would remain available for a range of purposes from home weatherization to rebates offsetting higher fuel costs for lower-income rural New Yorkers.

Of course, no new tax is ever welcomed with open arms. In recent years, moreover, carbon taxing has lost political standing with left and right alike. Right-wingers, in thrall to fossil fuels, denigrate the very idea of climate concern. Opinions on carbon pricing on the left, while far more nuanced, tend toward an “eat your peas” quality, seeing the promised revenues but not the powerful tides unleashed by the increased fuel prices.

Could a state carbon tax have a chance in New York this time around? I believe so, if only because MTA deficits are untenable and a statewide carbon tax looks like the least-bad long-term antidote.

Consider:

- New York wouldn’t be the first state to price all carbon emissions. California has done so for a decade, and, as noted, Washington just followed suit.

- Two-thirds of the $3 billion in carbon tax revenue could go to other, non-MTA uses across the state.

- Nearly half of the revenues would come from charges on fossil (natural) gas, the very fuel that climate activists are targeting in order to electrify heating and cooking while also shrinking climate-damaging methane leaks from pipelines, wells, and buildings.

- Carbon taxing’s regressive bias (it takes more dollars from the rich but more proportionally from the poor) would be blunted by its helping keep a lid on transit fares.

- The affluent suburban counties that will be on the hook for the carbon tax caught a big break by their exemption from the increase in the Payroll Mobility Tax. Moreover, some pro-climate suburbanites might even support a climate-helping carbon tax.

- Upstate households will be cushioned from the tax by the region’s preponderance of low-carbon electricity from nuclear, hydro, and wind power.

- Aid to transit could be packaged as an urban corrective to suburban- and rural-facing Inflation Reduction Act federal subsidies for solar panels, electric vehicles, and heat pumps. (Notably, the IRA does not fund urban-friendly mass transit and e-bikes.)

- Left-leaning climate-justice advocates who shy away from carbon pricing might warm to a policy that cuts emissions by attracting car trips to buses, trains, and subways.

This panoply of advantages points to diverse potential sources of support for a transit-benefitting state carbon tax:

- NYC transit and “livable streets” advocates;

- Economic-justice advocates who recognize affordable transit’s value in combating poverty;

- Climate campaigners who see carbon pricing as a complement to other carbon-cutting policies;

- Suburbanites concerned that future hikes in the Payroll Mobility Tax will come for them;

- “Electrify-everything” proponents working to eliminate fossil gas from residences and other buildings;

- Developers of low-carbon electricity — not just solar and wind providers but proponents of retaining the state’s four upstate reactors and building new ones;

- Energy-efficiency engineers, contractors, and workforces;

- Labor unions whose members fabricate, erect, and maintain the spectrum of green energy projects that a carbon tax will help make more abundant by making fossil sources costlier.

Competing Claimants?

Electricity producers in New York already pay a carbon fee under the multi-state Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) cap-and-trade program. In addition, Governor Hochul and the statewide climate coalition New York Renews have advanced competing carbon pricing concepts, both of them, somewhat confusingly, dubbed cap-and-invest. Hence, an MTA-focused carbon tax, which would employ a carbon-based charge on fossil fuels extracted or imported into New York State rather than a carbon cap enforced through sales of emission permits, wouldn’t arrive on a blank slate.

RGGI currently charges electricity producers around $14 for each ton of CO2 their generators emit. This levy is generating $365 million of statewide revenues a year, paid as surcharges on power bills, which goes to support investments in energy-efficiency and renewable electricity. While in theory the RGGI charge could be netted against the new carbon tax, the relative ease and importance of decarbonizing electricity production make it preferable to retain it and add the carbon price on top.

RGGI currently charges electricity producers around $14 for each ton of CO2 their generators emit. This levy is generating $365 million of statewide revenues a year, paid as surcharges on power bills, which goes to support investments in energy-efficiency and renewable electricity. While in theory the RGGI charge could be netted against the new carbon tax, the relative ease and importance of decarbonizing electricity production make it preferable to retain it and add the carbon price on top.

Cap-and-invest presents a trickier set of issues, partly because neither the governor’s prospective program included in the new budget nor NY Renews’ more elaborate plan has been fully fleshed out. In addition, the latter is the fruit of years of deliberation and consensus-building among the coalition’s hundreds of participant grassroots groups, who now constitute a formidable host.

At this writing, NY Renews envisions applying $10 billion in carbon revenues over several years in no less than 73 individual spending buckets grouped in four uber-categories: Climate Jobs and Infrastructure includes elements like aiding electric bus manufacture ($100 million) and offshore wind power supply chains ($300 million). Energy Affordability earmarks $1 billion to wipe out utility customer debt and $2 billion to support building electrification. Community & Worker Transition Assistance devotes $600 million to the “just transition” from jobs in carbon fuels to positions in renewable energy. And Community Directed Climate Solutions sets aside $2 billion to unspecified projects in historically underserved and overburdened urban neighborhoods and rural areas.

The NY Renews plan should be seen, then, as a holistic roadmap to make over not just how energy is supplied in the state but how it is consumed and governed. Billion-dollar-a-year allocations to the MTA aren’t the kind of investment its members have envisioned. Nevertheless, exploratory calculations suggest that the carbon payoff from service improvements paid for by a state carbon tax would be impressive.

As an illustration, I have calculated that an average 20% speed-up in subway trips achieved by running more trains at higher speeds would save straphangers and drivers each around 100 million hours a year (the latter from car trips switching to trains) while reducing car and truck emissions by 900,000 tons a year. Even more CO2 would be eliminated because of New York City’s improved competitive advantages vis-a-vis less “inherently green” suburbs and exurbs.

To be sure, so striking a gain in subway performance would almost certainly carry a price tag well over a billion dollars a year. Still, the prospective benefits underscore both the carbon-cutting potential of infusing new funds into subway service and the need to score competing claims for their climate value.

Broader Considerations and Next Steps

Over time, the carbon tax’s revenue base will shrink as its price incentives kick in and other carbon-cutting policies also gather steam. The resulting loss in tax revenues could be counteracted by periodically raising the per-ton tax rate. New York City could supplement the tax through revenue-generating street-management measures such as curbside pricing and other forms of road pricing.

Earlier this year, Community Services Society CEO (and MTA board member) David R. Jones and Riders Alliance executive director Betsy Plum proposed expanding New York City’s Fair Fares program to allow an additional 772,000 lower-income New Yorkers to qualify for half-fare transit passes. The cost, which they put at $142 million a year, should be a candidate for the carbon spending package.

This discussion has centered on the carbon tax’s creation of a new funding pot to maintain and improve transit affordability and performance. But taxing carbon emissions stands to benefit society in two other major ways. It will diminish financial incentives propping up carbon fuels and also support societal paradigms promoting care over harm.

A carbon tax is more than just a pay-for, in other words. Simply making it more expensive to buy and burn carbon fuels discourages fossil fuel use in a multiplicity of ways. Moreover, the very act of pricing carbon emissions can spur “externality taxing” in other realms, from congestion pricing to taxing the sugar content of soft drinks. Making New York the third U.S. state with broad-based carbon pricing will also add momentum to long-sought federal carbon emissions pricing.

Shoring up MTA finances, while reason enough to enact a state carbon tax, isn’t the lone consideration. The crisis of transit funding should be seen as a catalyst to pricing fossil fuels more closely to their true societal costs — a vital goal in its own right.

The next MTA funding crisis-as-opportunity will be upon us soon. The Legislature should move swiftly to study the benefits of taxing carbon emissions as a way to hold the line — and more — on transit fares and service, well in time for next winter’s budget negotiations. Transit and climate advocates and their counterparts in the Hochul administration should consider integrating a transit-focused carbon tax into their agendas.

Taking $3 billion a year for any public purpose, no matter how noble, is no small matter. The time to start selling a transit-supporting state carbon tax is now.

But it would not be extinguished. That’s where the climate movement comes in.

But it would not be extinguished. That’s where the climate movement comes in. The bank protests seem even less focused. Conoco doesn’t need financing from JPMorgan Chase or Wells Fargo to

The bank protests seem even less focused. Conoco doesn’t need financing from JPMorgan Chase or Wells Fargo to

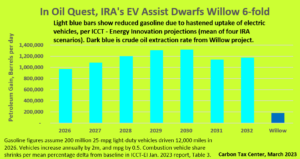

The supposed impossibility of reducing the use of gasoline by raising its price has been part and parcel of Big Green’s attachment to mpg standards — despite the fact that mileage reg’s do nothing to reduce driving and its vast negative consequences: not just traffic congestion but also poor health (sedentary living, car crashes, noise) and general unaffordability (car loan costs, upkeep expenses, costlier housing due to cars’ consuming urban and suburban land).

The supposed impossibility of reducing the use of gasoline by raising its price has been part and parcel of Big Green’s attachment to mpg standards — despite the fact that mileage reg’s do nothing to reduce driving and its vast negative consequences: not just traffic congestion but also poor health (sedentary living, car crashes, noise) and general unaffordability (car loan costs, upkeep expenses, costlier housing due to cars’ consuming urban and suburban land).

They had to move quickly before military police, tasked with securing the airport, saw what was happening. The rebels targeted 13 private jets parked or preparing for takeoff, at least two belonging to NetJets, the Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary that bills itself as the world’s largest jet company and sells fractional ownership shares in private business jets.

They had to move quickly before military police, tasked with securing the airport, saw what was happening. The rebels targeted 13 private jets parked or preparing for takeoff, at least two belonging to NetJets, the Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary that bills itself as the world’s largest jet company and sells fractional ownership shares in private business jets. The justification is unarguable. Large personal fortunes feed carbon consumption and make a mockery of programs to curb it. As well, the surplus wealth of the superrich is probably the lone source of capital that can finance the worldwide uptake of greener energy and also pay for adaptation where it’s most critical.

The justification is unarguable. Large personal fortunes feed carbon consumption and make a mockery of programs to curb it. As well, the surplus wealth of the superrich is probably the lone source of capital that can finance the worldwide uptake of greener energy and also pay for adaptation where it’s most critical. “What the Schiphol people needed to do is destroy the airplanes on the tarmac and then destroy the airplane manufacturers,” said an ecosaboteur named Stephen McRae, an acquaintance of one of the authors, who recently completed a six-year prison sentence for industrial sabotage. Although he no longer participates in such criminal acts of destruction, he has a point. The planes grounded on November 5 are already back in the air. That doesn’t diminish the value of what the Schiphol rebels did, however. Actions that disrupt carbon comfort without violence or hardship are morale-building, the material from which more actions and eventually mass movements are made.

“What the Schiphol people needed to do is destroy the airplanes on the tarmac and then destroy the airplane manufacturers,” said an ecosaboteur named Stephen McRae, an acquaintance of one of the authors, who recently completed a six-year prison sentence for industrial sabotage. Although he no longer participates in such criminal acts of destruction, he has a point. The planes grounded on November 5 are already back in the air. That doesn’t diminish the value of what the Schiphol rebels did, however. Actions that disrupt carbon comfort without violence or hardship are morale-building, the material from which more actions and eventually mass movements are made.

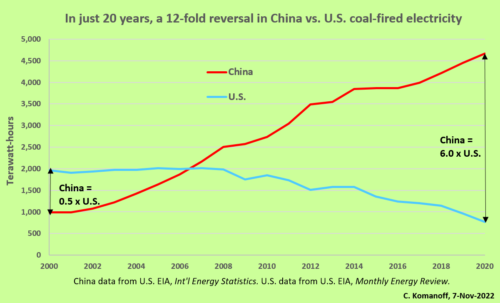

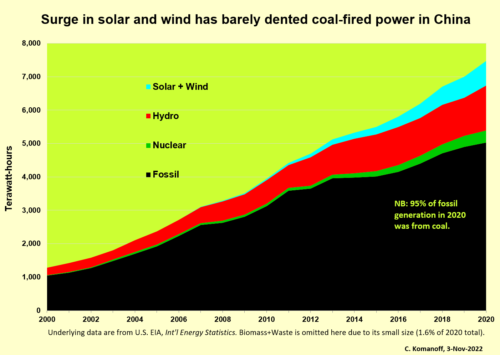

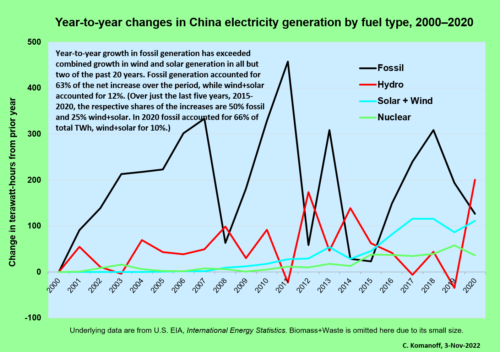

Those two years coincided with a flowering of climate optimism, with the U.S. and China reaching a bilateral agreement to curb emissions — ostensibly dissolving the “alliance of denial” by which both countries used each other’s inaction as a pretext to forego action on climate — and setting the stage for the 2015 Paris climate accord. Beginning in 2016, however, China’s fossil-fuel electricity generation (again, overwhelmingly coal-fired) recovered most of its prior increase pace. Year-to-year growth in fossil output has averaged 200 annual terawatt-hours since then.

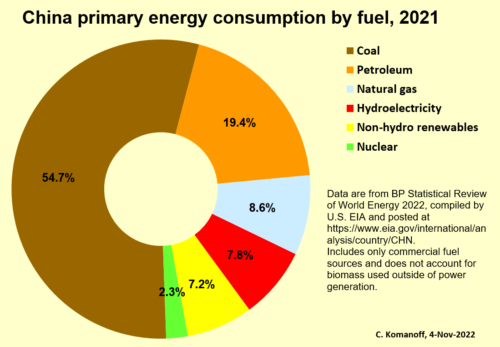

Those two years coincided with a flowering of climate optimism, with the U.S. and China reaching a bilateral agreement to curb emissions — ostensibly dissolving the “alliance of denial” by which both countries used each other’s inaction as a pretext to forego action on climate — and setting the stage for the 2015 Paris climate accord. Beginning in 2016, however, China’s fossil-fuel electricity generation (again, overwhelmingly coal-fired) recovered most of its prior increase pace. Year-to-year growth in fossil output has averaged 200 annual terawatt-hours since then. But in China, no single energy application rivals the burning of coal to produce electricity. It accounts for around one-third of the country’s primary energy consumption — a figure we computed by multiplying coal’s 55 percent share of 2021 China primary energy (see donut chart) and electricity’s estimated 60 percent share of the country’s total coal consumption (per the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s

But in China, no single energy application rivals the burning of coal to produce electricity. It accounts for around one-third of the country’s primary energy consumption — a figure we computed by multiplying coal’s 55 percent share of 2021 China primary energy (see donut chart) and electricity’s estimated 60 percent share of the country’s total coal consumption (per the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s

The Inflation Reduction Act likewise marks a turning point, at least for the time being, on long-running, world-damaging U.S. climate helplessness. True,

The Inflation Reduction Act likewise marks a turning point, at least for the time being, on long-running, world-damaging U.S. climate helplessness. True,

Even a fully intact Biden plan would have fallen short of its goals. Nevertheless, its scope and reach would have far surpassed any climate program by any major nation. Build Back Better’s carbon reductions and climate benefits would have been numerically substantial and would also have triggered parallel policies in other countries.

Even a fully intact Biden plan would have fallen short of its goals. Nevertheless, its scope and reach would have far surpassed any climate program by any major nation. Build Back Better’s carbon reductions and climate benefits would have been numerically substantial and would also have triggered parallel policies in other countries. During the run-up to that vote we published

During the run-up to that vote we published  D. Like Andreas Malm, we believe that direct action in defense of climate and earth needs to come to the fore, as we proposed in two posts last summer inspired by Malm’s book: Christopher Ketcham’s essay,

D. Like Andreas Malm, we believe that direct action in defense of climate and earth needs to come to the fore, as we proposed in two posts last summer inspired by Malm’s book: Christopher Ketcham’s essay,