A post today by New York Times economics columnist David Leonhardt, America Will Struggle After Coronavirus. These Charts Show Why., casts U.S. economic inequality in especially stark terms. Below, we reproduce the post’s most vivid graphs and striking prose.

Why highlight rampant economic inequality in America? Because we at Carbon Tax Center are convinced that U.S. political action to arrest climate change will remain largely stillborn so long as economic insecurity is rampant.

As I wrote earlier this month in a post co-authored with Christopher Ketcham for The Intercept:

People whose health is tenuous and whose pocketbook is empty can’t easily stand up for climate action, but they may do so if government has put them on a solid footing and, in the Green New Deal, provided a framework for paying them good wages to actually implement it.

Moreover, funding for the Green New Deal can and should come from America’s super-rich. “The past decade’s research and agitation on economic inequality must culminate,” we wrote,” in transmuting extreme private wealth into a new collectively shared wealth of renewable energy and sustainable communities.”

Of late, Leonhardt of The Times — a climate hawk and, until recently, carbon tax supporter before the politics of stand-alone carbon taxing became fraught — has written extensively on economic inequality and its dire consequences for Americans. Except where noted, all of the text below has been excerpted from his post that we linked to at the top.

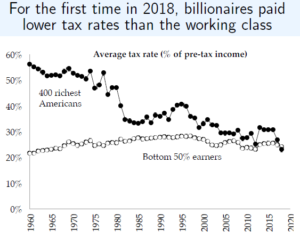

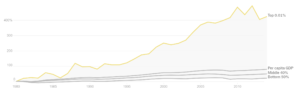

1. Incomes have stagnated. But not for the rich.

One way to think about the rise in inequality is to imagine how different the economy would be if inequality hadn’t soared over the past 40 to 50 years. In that scenario, with the same G.D.P. that we have today but with 1980 levels of inequality, every American household in the bottom 90 percent of income would be earning about $12,000 more — not just this year, but permanently. In effect, each household in this bottom 90 percent is sending a check for $12,000 to every household in the top 1 percent, year after year after year.

One way to think about the rise in inequality is to imagine how different the economy would be if inequality hadn’t soared over the past 40 to 50 years. In that scenario, with the same G.D.P. that we have today but with 1980 levels of inequality, every American household in the bottom 90 percent of income would be earning about $12,000 more — not just this year, but permanently. In effect, each household in this bottom 90 percent is sending a check for $12,000 to every household in the top 1 percent, year after year after year.

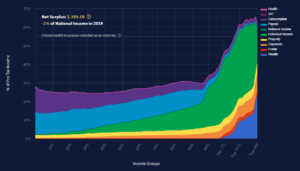

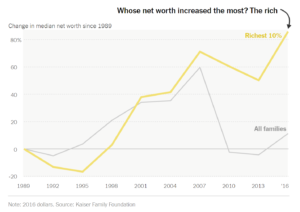

2. Whose net worth increased the most? The rich.

The trends on wealth are, if anything, more stark. In 2016 the median American household had a 30 percent lower net worth than the median household in 2007. How could this be, given the bull market during much of that period? The answer is that most Americans own little or no stock. Their main asset is their home. The affluent, of course, do tend to own stock, and the median net worth of the richest 10 percent of households rose 13 percent from 2007 to 2016 (the last year for which the Fed has released data).

The trends on wealth are, if anything, more stark. In 2016 the median American household had a 30 percent lower net worth than the median household in 2007. How could this be, given the bull market during much of that period? The answer is that most Americans own little or no stock. Their main asset is their home. The affluent, of course, do tend to own stock, and the median net worth of the richest 10 percent of households rose 13 percent from 2007 to 2016 (the last year for which the Fed has released data).

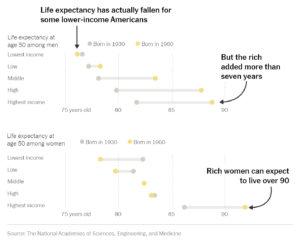

3. The richer live longer than the rest of us

The trends in health and life expectancy are also deeply worrisome. Rich and poor Americans used to have fairly similar lifespans. Now, however, Americans in the bottom fourth of the income distribution die about 13 years younger on average than those in the top fourth. No other rich country has suffered such slow growth in life expectancy. In 1980, Americans lived roughly as long as the British and French did. Not anymore.

[Back to CTC]

These are highlights of Leonhardt’s post. Much of it — not excerpted here — concerns equally weighty matters like racial income and wealth disparities, the widening life-expectancy gap between the U.S. and other rich nations, our “uniquely expensive and inefficient medical system,” and the tripling since the early 1990s in rates of “deaths of despair” — from suicide, alcoholism and drug abuse — among American adults (ages 25 to 64) without a four-year college degree. (April 14 addendum: The Times today published an opinion piece by economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton, authors of “Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism,” arguing that Americas unfettered for-profit health-care system “takes from the poor and working class to generate wealth for the already wealthy.”)

And more: the chronic-pain gap and one-parent family gap between families on either side of the class divide; the decline of labor unions that formerly gave non-college workers social solidarity as well as economic strength; and of course differences between labor participation (a more accurate and telling metric than unemployment rates, which don’t reflect would-be workers who have dropped out of the workforce).

Leonhardt’s article conludes:

Given all of this, it makes sense that so many Americans have soured on their own country. For almost 20 years, through economic booms and busts and through presidencies of both parties, most Americans have said the country was headed in the wrong direction. They’re right about that.

To repeat: CTC began bringing America’s stark inequality to the fore late last year, in this brief account and this longer narrative, from two convictions: that wealth taxes must be the primary means to pay for the Green New Deal, and that support for concerted climate action depends on making Americans more secure and making America more just.

The work continues.

Note: Leonhardt’s July 3 follow-on post, The U.S. Is Lagging Behind Many Rich Countries. These Charts Show Why., adds to this rich vein with trenchant comparisons of U.S. with western Europe on union membership, minimum wage rates, life expectancy, health care costs, etc.