Conversion of a Climate-Change Skeptic (NYT)

Search Results for: going global

The Carbon Tax Revenue Menu

Getting the politics to align for a carbon tax requires the right blend of honey and vinegar. For years, advocates’ and opponents’ attention alike has focused on the vinegar – the tax part. Lately, though, we’ve noticed growing interest about how to best spread the honey — the potentially huge revenues a carbon tax would generate. Here’s a primer on the options: what they are, how they would work, their merits and drawbacks, and who’s pushing them hardest.

Setting the initial tax rate at $15/T CO2 and increasing it by that amount each year (reflecting the maximum carbon tax rate and ramp-up of Rep. Larson’s bill) we estimate that the Treasury would take in approximately $80 billion in revenue in the first year. (This calculation uses the Carbon Tax Center’s spreadsheet model.) This amount would rise each year, though at slightly less than a linear rate as carbon reductions kicked in, reaching around $600 billion by the tenth year.

The allure of carbon tax revenue also offers a growing incentive for other nations to match a U.S. carbon tax in order to avoid WTO-sanctioned border tax adjustments, capturing the revenue themselves. Indeed, Brookings economist Adele Morris calls a carbon tax a “two-fer” because along with a growing revenue stream would come substantial CO2 emissions reductions. For the U.S., based on historic price-elasticities, CTC’s model projects a 30% reduction in climate-damaging CO2 emissions by the tenth year, compared to 2005 levels.

Six hundred billion (again, that’s the projected take in the tenth year from an ambitious carbon tax) is a lot of revenue, equivalent to around a quarter of federal tax receipts. As Ian Parry and Roberton Williams recently explained in “Moving U.S. Climate Policy Forward: Are Carbon Taxes the Only Good Alternative?” (Resources for the Future), the efficiency advantages of a carbon tax depend on using the revenue wisely. Not surprisingly, there are loads of claimants. Here’s a guide to the most prominent ones, sequenced more or less from the political left to right:

a) “Dividend.” Climate scientist James Hansen contends that to support a steadily-rising CO2 price, the public needs to see the money — every month. He calls his proposal “fee & dividend.” Senators Cantwell (D-WA) and Collins (R-ME) introduced the “CLEAR” bill which uses “price discovery” via a cap to set its carbon tax which would begin at a price between $7 and $21/T CO2, increasing 5.5% each year. CLEAR would return 75% of revenue via direct “dividends” and dedicate the remaining 25% to a fund for transition assistance and reduction of non-CO2 emissions. Rep. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD) also introduced a cap & dividend bill in the Ways & Means Committee. It relies on a cap to set the CO2 price indirectly, aiming for 85% reductions (over 2005 levels) by 2050. Because of its similar emissions trajectory, we’d expect Van Hollen’s bill to generate similar revenue to Rep. Larson’s bill: roughly $80 billion in the first year, rising to about $600 billion within a decade. Both the CLEAR bill and the Van Hollen bill bear the intellectual and organizing stamp of social entrepreneur Peter Barnes, who founded “Cap & Dividend,” and Peter’s allies including the Chesapeake Climate Action Network.

b) Payroll tax rebate. Rep. John Larson’s “America’s Energy Security Trust Fund Act” pairs a carbon tax with rebates of payroll taxes on earnings. As articulated by Tufts University economist Gilbert Metcalf (now serving at the Treasury Department’s energy office), Larson’s proposal has the appeal of broad fairness. It would distribute revenue very evenly across both income and regions. Because Rep. Larson’s approach rebates payroll taxes via a credit on federal income taxes — it would rebate the payroll tax on the first $3600 of income in the first year, with that threshold and rising over time — it avoids tangling with the Social Security Trust fund.

Economist and former Undersecretary of Commerce Rob Shapiro supports the approach of a payroll tax rebate, arguing that cutting payroll taxes could spur job growth. Social entrepreneur Bill Drayton, founder of “Get America Working,” is also a strong advocate of using carbon revenue to cut payroll taxes in order to stimulate employment while reducing emissions. Al Gore captured the idea with the phrase, “tax what we burn, not what we earn.” Former Rep. Bob Inglis (R-SC) introduced the “raise wages, cut carbon” bill co-sponsored by Rep. Jeff Flake (R-Az). Conservative economists Greg Mankiw and Douglas Holtz-Eakin, both of whom have advised Republican presidents and candidates, have also supported shifting tax burdens from payrolls to carbon emitters. And the Progressive Democrats of America endorsed the Larson bill.

c) Deficit reduction. Brookings economists including Ted Gayer and Adele Morris have been pointing out the potential for climate policy to reduce deficits. While deficit reduction isn’t revenue return in the immediate sense that Dr. Hansen suggests, Morris points out that deficit reduction will benefit future taxpayers by paying down at least part of the nation’s debt, rather than letting it continue accumulating interest. In this way, she suggests, the impulse to help future generations via foresighted climate policy would have a natural fiscal correlative of reducing future tax burdens.

Supporters of applying carbon tax revenues to deficit reduction include MIT’s Michael Greenstone (chair of the Brookings Hamilton Project on climate and energy policy) and Alice Rivlin, founding director of the Congressional Budget Office, who co-chaired the Bipartisan Policy Institute’s alternative to the Obama deficit commission. Prof. Metcalf proposed a carbon tax to the commission, with revenue return as “transition assistance” in the early years, shifting to deficit reduction in later years. As Irwin Stelzer of the conservative Hudson Institute recently pointed out, when the options to close budget gaps sift down to unpopular alternatives such as a value added tax (regressive and annoying, as EU residents will attest) or curbing home mortgage deductions, a carbon tax may emerge with greater appeal. While Keynesians argue that the present weak economy militates against any net increase in taxes, a phased-in allocation of carbon tax revenues to deficit reduction such as Prof. Metcalf proposes may circumvent that objection.

d) Income tax cuts. Greg Mankiw has suggested cutting income taxes as an alternative to payroll tax cuts to return carbon tax revenues; those Form 1040’s could include a carbon rebate drawn from those revenues for every taxpayer. Revenue could be returned via a lump sum credit (which would be income-progressive) or by reducing income tax rates (arguably more stimulative of income-earning activity).

e) Corporate income tax (CIT) rate cut. At a recent AEI event “Whither the Carbon Tax,” AEI economist Kevin Hassett argued for a carbon tax paired with a reduction in the corporate income tax rate. The Wyden-Coates tax reform bill proposes to reduce top CIT rates and make up the revenue by closing numerous exemptions, indicating interest on the Hill. Adherents of CIT rate cuts point to IMF studies saying that U.S. CIT rates are among the world’s highest, asserting that these taxes are especially stifling of business activity and employment. Hassett and his AEI collegue Aparna Mathur argue that CIT’s are passed through as higher prices for consumers and passed back to the factors of production: labor (in the form of reduced wages) and capital (in the form of reduced corporate earnings). They estimate that using carbon tax revenue to cut the effective CIT rate would result in return of about 40% of revenue to wage-earners, which they assert would give the CIT to carbon tax shift a net progressive effect. Their conclusion may be a stretch, given that real wages have remained stagnant or fallen for decades while corporate profits are rising briskly, but a CIT cut has strong salience for conservatives and business leaders.

f) The sampler platter. The options listed above can be mixed and matched. In fact, British Columbia’s carbon tax (which started at $10/t CO2 in 2008 and rises $5/t each year — it notches up to $25 per metric ton on July 1) launched with a distribution of a $100 direct “dividend” to each taxpayer even before the carbon tax was levied, and is now returning revenue via cuts in payroll, income and corporate tax rates. Former BC Premier Gordon Campbell was re-elected to a third term in 2009 after enacting the carbon tax with this mix of revenue return measures, perhaps indicating that a diverse approach to revenue return can have broad and sustained appeal.

Each of the revenue options has important economic and political advantages as well as disadvantages. At the June 1 AEI event, Kevin Hassett decried Senator Cantwell’s direct “dividend” as “terrible policy” because it foregoes the efficiency advantage of using carbon tax revenue to reduce or possibly eliminate other taxes that dampen economic activity. In 2007 Hassett and his AEI colleague Ken Green published an essay aguing for a carbon tax shift as a “no regrets” policy for conservatives, because its tax reform benefits would make it worthwhile even without climate benefits. They pointed to the work of Stanford’s Lawrence Goulder who concludes that the benefit of reducing other distortionary taxes can be large enough to offset some or all of the dampening effect of adding a carbon tax, a phenomenon known as a “double dividend.”

Still, the potential political attractiveness of direct distribution of revenue can hardly be overstated. Dr. Hansen is no politician and doesn’t claim to be an economist, but he sticks to the “dividend” or “green check” while noting that because of its clear and briskly rising price, Rep. Larson’s approach is nevertheless the best climate option on the table. Rep. Van Hollen, outgoing chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, certainly knows a thing or two about politics, and Senator Cantwell very effectively made the case for her “cap & dividend” approach last month at Brookings. But even she seems to be looking at other items on the revenue return menu. For the first time, she suggested appropriating some carbon revenue for deficit reduction, confirming that as high summer arrives in Washington, fiscal matters remain the topic for this Congress.

Photo: Flickr.

Would a Methane Tax Make Natural Gas a Green-Enough “Bridge” Fuel?

(co-authored with Charles Komanoff)

From a climate standpoint, natural gas appears to have two huge advantages over coal. First, gas combustion releases 40% less carbon dioxide per Btu produced than does coal. Second, gas-fired power plants using “combined cycle technology” require 40% fewer Btu’s to produce each kilowatt-hour than coal-fired plants. Chain those advantages, and you find that new gas-fired power plants can produce 2.7 – 2.8 times as much electricity as a typical coal-fired generator while emitting the same CO2. No wonder gas is touted as a “bridge fuel” to renewables from coal, which accounts for 45% of U.S. electricity generation and a third of U.S. carbon dioxide emissions.

Of late, however, scrutiny of “fugitive” emissions from gas extraction and transmission is calling into question the assumption that gas is more benign for Earth’s climate than coal. The new wrinkle isn’t CO2 but methane itself, a potent greenhouse gas in its own right which can escape into the atmosphere at almost every step of the natural gas “fuel cycle.”

Natural gas (or simply “gas”) is 99% methane (CH4). Viewed over a 100-year time horizon (as the 2008 IPCC Fourth Assessment report did), methane’s greenhouse potency — its heat-trapping capacity, per pound of gas in the atmosphere — is roughly 25 times that of CO2. And if a 20-year timeframe is used, the greenhouse potency of a pound of methane becomes 72 times that of a pound of carbon dioxide. (The difference between the ratios arises because methane in the atmosphere breaks down about ten times as fast as CO2 — roughly a decade on average vs. a century for CO2.)

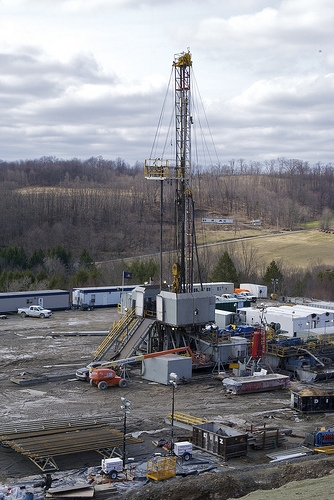

What’s bringing the issue of fugitive methane emissions to a boil is  “hydrofracking” (or “fracking”). A highly invasive drilling process that releases gas by subjecting underground shale rock to hydraulic fracturing, fracking is being touted as a global-energy game changer. (“How Shale Gas Is Going To Rock The World” was the title of a May 2010 Wall Street Journal “special report.”) But fracking is also an emerging source of massive air, soil and water pollution in states such as Pennsylvania that are the epicenter of the fracking boom.

“hydrofracking” (or “fracking”). A highly invasive drilling process that releases gas by subjecting underground shale rock to hydraulic fracturing, fracking is being touted as a global-energy game changer. (“How Shale Gas Is Going To Rock The World” was the title of a May 2010 Wall Street Journal “special report.”) But fracking is also an emerging source of massive air, soil and water pollution in states such as Pennsylvania that are the epicenter of the fracking boom.

In a recently-published peer-reviewed article, Prof. Robert Howarth and colleagues at Cornell University calculated methane releases from fracking and combined them with EPA data on gas pipeline leak rates to estimate methane losses across the gas fuel cycle. Their findings are sobering. For every 100 cubic feet (the standard volume measurement) of natural gas “gathered” at the well and transferred to the transmission system:

- 0.6 – 3.2 cubic feet are released to the atmosphere in the frack drilling process, and

- 1.4 – 3.6 cubic feet of gas leaks into the atmosphere from the distribution system.

(EPA is expected to revise these estimates upward in view of more complete reporting showing greater leak rates, according to Howarth.)

Howarth et al. caution that their figures are based on very limited data, and are calling for further study. Nevertheless, their preliminary conclusion is that due to fugitive emissions in both the fracking process and gas pipelines, frack gas is causing as much global warming and climate change, per unit of energy output, as is coal. While that result is calculated for a 20-year timeframe, which understates the overall impact of carbon dioxide and, therefore, of coal, even over a 100-year timeframe fugitive emissions appear to take a huge bite out of any climate advantages that might otherwise be ascribed to natural gas.

It’s important to note that the Howarth analysis doesn’t take into account the second of the two “40% advantages” that we noted at the beginning of this post — the one reflecting the greater electric-generation efficiency of combined cycle gas turbines over conventional coal-fired steam turbines. This omission is significant in light of the fact that this efficiency edge has made combined cycle technology the overwhelming choice for recently-completed and proposed new gas-fired power plants. But regardless of the exact quantitative comparison between coal and frack gas, Howarth et al. are focusing much-needed attention on what now appears to have been the even starker omission (by most analysts) of substantial fugitive methane emissions in the natural gas fuel cycle.

Furthermore, as a frack gas drilling boom sweeps over the Marcellus Shale region of southwestern New York and huge swaths of Pennsylvania and West Virginia, residents are learning the hard way that fracking leaves vast amounts of dangerous chemicals in groundwater while also dumping polluted water, some of it radioactive, into rivers and streams. Congress is barely beginning to consider measures to close loopholes that exempt fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act and the Clean Air Act, and these defensive initiatives are far behind the “NAT GAS” bill pushed by billionaire hydrocarbon mogul T. Boone Pickens to jumpstart a huge market for natural gas vehicles by subsidizing conversion of fleet vehicles and heavy trucks to gas.

Is there a way to legislate a clampdown on fugitive emissions of methane? Regulation requiring capture of gas, especially during the flow-back phase of gas drilling, should certainly be considered. But economic incentives are also worth a close look. Several carbon tax proposals would tax other greenhouse gases, including methane because, after CO2, it’s the top greenhouse gas driving Earth’s climate into instability. If, as Howarth and his colleagues have documented, fugitive methane emissions are a serious threat to Earth’s climate, could a tax on those methane emissions at their CO2-equivalent price correct the apparent market failure that leaves drillers willing to vent valuable and very climate-damaging methane?

We think so. Because methane is (at least) 25 times as potent a greenhouse gas as CO2, let’s consider a fugitive methane tax of 25 times the carbon tax rate, to reflect that potency. We calculate that a tax of $25 per ton of CO2 — to pick a modest, but not insignificant level — would imply a tax on fugitive gas of $13 per thousand cubic feet.* Since natural gas currently sells in wholesale markets for around $4 per thousand cubic feet (down from as much as $12 before the onset of the financial crisis), this tax would more than quadruple the incentive to capture methane provided by its current market price. That would appear to be a lot of leverage to capture fugitive methane, even from a fee pegged to a relatively modest carbon tax.

Howarth et al. report a huge range of fugitive methane emissions over the life of different frack wells — from a low of 140,000 cu ft to a high of 6,800,000. At $13 / 1000 cu ft, the tax on those fugitive emissions would range from only around $60,000 per well to as much as several million dollars. (This enormous range is partly an artifact of the limited data available to Howarth.) While the low end is just peanuts to frack drillers, the high end is a significant fraction of the $2 to $10 million or more cost to drill a well (see p 25 of linked document). It seems reasonable to expect that this tax, along with the market price of gas and the expectation of a rising CO2 (and equivalent fugitive gas) charge, would encourage deployment of equipment to capture, compress and store gas, at least at larger wells.

As both Howarth et al. and a recent report by the Post Carbon Institute point out, gas pipelines generally aren’t built and connected until wells are completed. Thus, well drillers who aren’t typically in the business of selling gas (and may not even own the rights to it) may not have ready access to gas pipelines and markets. This “split incentive,” along with the rush to establish and maintain drilling rights before leases expire, may help explain the reckless, wasteful discharge of climate-damaging methane into the atmosphere from frack wells. But gas can be compressed and transported by truck, so we’d expect that the price incentives of a rising greenhouse gas tax on fugitive methane would push well drillers to find ways to capture more of their emissions. Similarly, a substantial price signal should induce pipeline companies to repair and monitor leaking distribution systems. In this way, more of the lifecycle combustion advantages of natural gas as a true transition fuel could be realized.

As for fracking’s often-horrific “other” emissions: tough and comprehensive regulations are sorely needed. Congress should start with the “FRAC Act” H.R. 1084/S. 587 introduced by Rep. DeGette (D-CO) and Sen. Casey (D-PA), which would eliminate fracking’s exemption from the Safe Drinking Water Act; and the “BREATHE Act,” H.R. 1204 by Rep. Polis (D-CO.), which would bring fracking under the Clean Air Act.

* Authors’ calculation:

A $25/ton CO2 tax x 25x GHG potential = $625/ton CH4.

$625/2000 lb x 44 lb/1000 cu ft x 1000 cu ft/ 1.02 MM Btu = $13.5 /MM Btu

Flickr Photo: Frack Well in Dimock, PA. Brandi Lynn.

Add OPEC Profiteering to List of Reasons to Ditch Cap-and-Trade

The drawbacks of the cap-and-trade approach for pricing and reducing carbon emissions are legion. They include complexity, volatility, lack of price predictability, vulnerability to financial speculation, and impossibility of harmonizing across borders. Now there’s another, courtesy of a 2010 report by an economist at the World Bank: Institution of a cap-based emissions program by oil-importing countries works to increase oil exporters’ market power, revenue and profits; whereas a carbon tax would have the opposite effect.

That’s the conclusion we draw from Jon Strand’s “Taxes and Caps as Climate Policy Instruments with Domestic and Imported Fuels.” As Dr. Strand, who chairs the economics department at the University of Oslo and has served as a senior economist at the World Bank since 2008, wrote:

[A] c-a-t [cap-and-trade] solution … leaves [oil importing countries] more vulnerable to adverse strategic manipulation of fuel prices by monopolistic exporters.[ [Conversely,] a tax is more efficient than a cap at extracting rent from fuel (oil) exporters. [Abstract and p. 32]

For his paper, Strand modeled a simple situation: Region A consumes two classes of fuels: imported oil and domestically-produced energy. Region B (interpreted as OPEC, plus Russia) exports fuel (oil) to Region A. Each region seeks to maximize revenue in response to the strategy of the other region. Strand concluded that the consuming region would be strategically weaker vis-à-vis the producing region under a carbon emissions cap than under an equivalent carbon tax.

For his paper, Strand modeled a simple situation: Region A consumes two classes of fuels: imported oil and domestically-produced energy. Region B (interpreted as OPEC, plus Russia) exports fuel (oil) to Region A. Each region seeks to maximize revenue in response to the strategy of the other region. Strand concluded that the consuming region would be strategically weaker vis-à-vis the producing region under a carbon emissions cap than under an equivalent carbon tax.

Here’s why: Micro-economic theory teaches that a monopolist sets an optimum price to maximize revenue. Set the price too high, and sales volume falls, more than offsetting the increased revenue generated by a higher price. Set the price too low, and increased sales don’t overcome the lost revenue. Now picture a carbon emissions cap legislated by the importer, Region A. Because the cap constrains sales volume, the monopolist exporter can shift its (optimal) price upward without cutting sales volume. In contrast, were the importer to implement a carbon tax, this would reduce the exporter’s optimal (revenue-maximizing), price because the higher, tax-including price would reduce sales.

As Strand puts it, under cap-and-trade,

[T]he exporter strategically adjusts its tax [or export price] so as to extract maximum rent from the importer, at the given (exogenous) cap, leading to a zero equilibrium value for tradeable emissions quotas in the importer region.

Strand’s analysis points to a fundamental issue that cap-and-trade promoters tend to play down. A cap is an indirect way to set a price by limiting supply. But if someone upstream — the fuel exporter or its government — raises the price (or tax), the allowance price will fall. In the extreme, the exporter could raise the price enough to achieve the emissions reductions mandated by a cap and drive the allowance price down to zero. In other words, the importing nation’s cap enables the fuel exporter to reap a windfall by raising prices without sacrificing sales because falling allowance prices under the cap will tend to “absorb” the exporter’s price increase. In contrast, with a fixed (or gradually-rising) carbon tax, the exporter will be pressed to reduce prices to compensate for the tax in order to maintain sales volume at the revenue-maximizing point.

Strand isn’t the first economist to suggest this advantage of a carbon tax. In 2009, economists at the University of Ontario concluded that in addition to reducing CO2 pollution and providing revenue with which to reduce other taxes, carbon taxes offer a third important benefit: transferring revenue from OPEC to oil-importing countries, reducing OPEC’s monopoly power. Similarly, in an earlier (2002) paper, “Can Carbon Tax Eat Opec’s Rents?,” economists from MIT and the Helsinki School of Economics concluded that a “carbon tax can be used to reduce the producer price of fossil fuels and thereby to shift resource rents from the resource-exporting countries.”

The European Union’s cap-and-trade experience during the current steep recession offers insight into caps’ perverse interaction with “exogenous” (outside) forces. The recession curbed economic activity, and at the same time oil prices rose. In response, energy demand fell, driving down the price of CO2 allowances needed to burn fossil fuels. The EU’s emissions have declined during recent years, not because the cap is doing much to constrain emissions, but because those exogenous factors have reduced demand. Indeed, in the “uncapped” U.S., the trend of falling emissions very closely matches the downward emissions trend in the EU. In effect, a slow economy cut demand, and higher exporter oil prices captured “rent” from under the cap, holding allowance prices down and making it less effective at “putting a price on CO2” that would induce long term investment in alternative energy.

As we learned last week from a diplomatic cable written by U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, released by Wikileaks, “[D]onors in Saudi Arabia constitute the most significant source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide.” (NYT, Dec. 5.) Saudi Arabia, of course, is the world’s largest petroleum exporter and the second largest crude oil producer (after Russia). The Saudi economy is utterly dependent on oil and petroleum-related industries, including petrochemicals and petroleum refining, with oil export revenues accounting for 90 percent of total Saudi state revenues and more than 40 percent of the country’s GDP.

As we learned last week from a diplomatic cable written by U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, released by Wikileaks, “[D]onors in Saudi Arabia constitute the most significant source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide.” (NYT, Dec. 5.) Saudi Arabia, of course, is the world’s largest petroleum exporter and the second largest crude oil producer (after Russia). The Saudi economy is utterly dependent on oil and petroleum-related industries, including petrochemicals and petroleum refining, with oil export revenues accounting for 90 percent of total Saudi state revenues and more than 40 percent of the country’s GDP.

It thus may not be much of a stretch to ask if a U.S. carbon cap (especially when added to an EU cap) could wind up helping funnel money to Islamic fundamentalists with terrorist inclinations. Obviously, Strand’s analysis oversimplifies the situation — oil exporters are not a strict monopoly, they do compete somewhat, and energy technology or consumption patterns could change the dynamic. But it’s worth noting that economic analysis suggests that a carbon tax would tend to work against the interests of the oil cartel, while cap-and-trade would tend to reinforce the cartel’s price-setting leverage.

Photos: Flickr–foreclosurepro, digitaltrends.

P.S. This Just In:

Ecuador Asks OPEC to Support Oil Tax on Importers (Bloomberg, 12/11/10).

“With the first global tax on carbon emissions OPEC would achieve the most efficient and just way to do what Kyoto has failed to: make carbon emitters internalize the effects of their actions and pay for the pollution they create,” Ecuador’s President Rafael Correa said.

New Converts to Carbon Tax: Welcome Aboard, Now Start Rowing

(Note: NYT DotEarth blogger Andy Revkin linked to this post today in a piece that has more from Bill Gates on carbon pricing. Click here. – C.K., Sept 2.)

Last week, Bill Gates. This week, Bjorn Lomborg. With the world’s #1 software magnate and the man whom the Guardian labeled “the world’s most high-profile climate change skeptic” both endorsing a carbon tax, is the tide of influential opinion on climate policy and carbon pricing turning?

Yes and no.

Let’s look at Lomborg first. The Danish policy analyst built a lucrative career lambasting climate-change advocates as scaremongers who would consign millions to early death by devoting resources to decarbonizing the world economy rather than fighting killer diseases like malaria. But in a new book to be published next month, the self-styled “skeptical environmentalist” reportedly will call global warming “one of the chief concerns facing the world today” and “a challenge humanity must confront.” According to the Guardian, Lomborg will urge investing tens of billions of dollars a year to tackle climate change, with the funds to be raised through a carbon tax.

In somewhat overheated prose, the Guardian called Lomborg’s new-found resolve to combat global warming “an apparent U-turn that will give a huge boost to the embattled environmental lobby.”

Gates, on the other hand, has long worried about climate change. But in an interview in Technology Review last week, he added a new wrinkle: criticism of cap-and-trade:

TR: [A]lmost everyone agrees that there needs to be a price on carbon–whether a Pigovian tax or a cap-and-trade system. Without a price, there’s going be very little incentive to do the kinds of research, or create the kinds of technologies, or build out the kind of infrastructure, that we need.

Gates: No, that’s not right. It’s ideal to have a carbon tax, not just a price on carbon, which is this fuzzy term that includes cap-and-trade.

TR: Well, ideally, you’d do a Pigovian tax —

Gates: No, not a Pigovian tax. A Pigovian tax is where you pay for the damage. Here, you’re not paying for the damage — you can’t pay for the damage. You’re using the tax to create a mode shift to a different form of energy generation.

TR: That sounds very rational, pragmatically feasible, and humane. It also sounds politically unlikely.

Gates: Which is more likely: a [hidden] carbon tax [Gates’ way of describing cap-and-trade] with all sorts of markets and options and uncertainties about prices, and traders in the middle, and confusion about who initially gets the most advantage? Or a regulatory thing that says you mark every coal plant in the country with when it has to be retired, and a 2 percent tax to fund the R&D so that utilities know they can buy a plant that’s emitting hardly any CO2?

Gates’ disparagement of cap-and-trade is striking. But neither his 2% carbon tax nor Lomborg’s, which appears to resemble Gates’ in magnitude and function ─ funding energy R&D ─ is going to end the reign of fossil fuels in the foreseeable future.

The notion of an R&D solution is alluring. Who doesn’t want there to be global warming antidotes lurking in garages and labs, waiting for funding to unlock them? But it’s a chimera. Even with unlimited research funding, no technological breakthroughs can dislodge carbon-based fuels from dominion over the world’s energy economy. Fossil fuels’ energy density is too great, and their positional advantages of infrastructure and institutions too powerful.

Yes, subsidies can help push renewables past the “hump” in the S-curve to where scale economies can kick in and take a few bites out of the fossil fuel pie. But as New Republic blogger Brad Plumer pointed out recently, “Government subsidies just don’t pack the same punch as a market price on carbon pollution.” When a commodity or activity causes harm, the surest way to reduce it isn’t to subsidize a thousand and one alternatives but to directly discourage the thing by internalizing the cost of the harm into its price.

Ironically, Barack Obama appeared to grasp this during his run for the presidency. In a February 2008 interview with the San Antonio Express he enthused over the idea of a carbon tax:

Q. Have you considered … taxing emerging energy forms, for example, say a penny per kilowatt hour on wind energy?

A. Well, that’s clean energy, and we want to drive down the cost of that, not raise it. We need to give them subsidies so they can start developing that. What we ought to tax is dirty energy, like coal and, to a lesser extent, natural gas. (emphasis added)

How big a carbon tax is needed? A lot more than 2%. Raising electricity prices by 2%, if that’s what Gates envisions, would reduce electricity usage by an estimated 1.4% over the long run. Assuming, as modeling at the Carbon Tax Center suggests (xls), that fuel substitution (gas and nuclear for coal, wind and solar for gas, etc.) contributes roughly two units of carbon reduction for each unit gained from demand destruction, the total impact of the Gates tax on carbon emissions from the electricity sector would be just 4-5%. Since other sectors are less price-elastic, the average economy-wide reduction would be even less, probably just a few percent.

Contrast this with the bill introduced by Rep. John Larson (America’s Energy Security Trust Fund Act of 2009, H.R. 1337), which has a first-year carbon tax of $15 per ton of CO2 increasing steadily and predictably at $10-$15/ton each year, that would cut (xls) U.S. carbon emissions by approximately 30% by 2020, or an order of magnitude more than Gates-Lomborg carbon taxes. And Larson would return the vast bulk of carbon revenues to workers’ paychecks while setting aside a fund for the sort of clean energy R&D that Gates and Lomborg espouse.

Why the 10-fold difference in impact? A large carbon tax like Rep. Larson’s would create profound incentives: on the demand side to use less energy (via billions of decisions at household and social levels), and on the supply side to shift fuels and power to low- and zero-carbon sources (via thousands of decisions by entrepreneurs, utilities and energy companies). A mere 2% carbon tax, even one with revenues allocated to R&D, would not.

In his Technololgy Review interview, Gates at least coupled his carbon tax with a notion of ordering utilities to shut down CO2-intensive plants at such and such a time:

And then you just take all the carbon-emitting plants, you look at their lifetime, and you say on a certain date this one has to be shut down, and when a new one is put in place, it has to be low-CO2-emitting.

But how this would come to pass in the absence of price signals and corrections justifying it financially is, to be charitable, unclear.

Both Gates and Lomborg deserve plaudits for their disavowals: of cap-and-trade by Gates, of climate-change denialism by Lomborg; and for embracing the idea of a carbon tax. They now need to see the next light: to have the necessary impact, a carbon tax can start modestly but must keep rising predictably. Fortunately, we have the example of British Columbia to show that an upward-trending carbon tax of the needed size can be politically popular if the revenue is returned to the public.

Memo to Sen. Kerry: Climate Science Includes Economics

U.S. climate activists are gleeful at Sen. John Kerry’s demolition of a sometime climate skeptic at a Senate Finance Committee hearing on Tuesday, and justly so. Ken Green, a resident scholar for the corporate-financed American Enterprise Institute, won the respect of carbon tax advocates two years ago, when he co-authored an AEI report that powerfully made the case for a revenue-neutral carbon tax over a cap-and-trade system. But as an invited witness on Climate Change Legislation: Considerations for Future Jobs, Green attempted to argue that Earth’s ecosystems and human civilization could safely accommodate a global temperature rise of 2 degrees Celsius, though he admitted that any larger temperature rises would be dangerous. Kerry skillfully “outed” Green as an amateur in climatology who had published no peer-reviewed studies and could point to none to support his climate blandishments.

The interchange, summarized in a 6½-minute video assembled by Joe Romm at Climate Progress, showcases Sen. Kerry’s skill as a cross-examiner and reveals just how flimsy and muddled the case questioning the climate crisis really is. Lost in the euphoria, however, is evidence of the Senator’s own confusion — not on the need to act to avert climate catastrophe, but on the workings of competing means of pricing carbon emissions.

In an earlier part of this week’s hearing, Sen. Kerry repeated a point he made in an August 4 Finance Committee hearing on Climate Change Legislation: Allowance and Revenue Distribution: a carbon tax wouldn’t reduce emissions, Kerry claimed, because polluters would “just pay the tax,” whereas a cap would force them into making the desired reductions.

In an earlier part of this week’s hearing, Sen. Kerry repeated a point he made in an August 4 Finance Committee hearing on Climate Change Legislation: Allowance and Revenue Distribution: a carbon tax wouldn’t reduce emissions, Kerry claimed, because polluters would “just pay the tax,” whereas a cap would force them into making the desired reductions.

Of course, as anyone versed in climate economics knows, and as the economist-witnesses explained in August, a carbon price of, say, $20/ton would produce the same emissions reductions whether the price was set by traders in a carbon market or directly via a fee on fossil fuel producers. Under a cap with a $20/ton permit price, emitters would have no greater (and no less) incentive to reduce emissions than they would under a $20/ton tax. Reductions that can be made for up to $20 per ton will be made in either system because they will yield the same savings — as permits that wouldn’t need to be purchased under a cap, or as taxes that wouldn’t have to be paid under a tax. Similarly, reductions costing more than the set price won’t be made because it will be cheaper to “just buy the permits” (to adapt Sen. Kerry’s phrase), or “just pay the tax.”

Under either system, then, emitters retain the flexibility to make reductions when those reductions are cheaper than the carbon price and to pay the allowance cost or tax if that turns out to be cheaper. That flexibility about where, when and how to make reductions is why either a carbon cap or tax is more efficient than source-specific regulations which would force emissions reductions at times and places where they’re more expensive and would miss some reductions that were cheaper.

In the August hearing, Sen. Kerry questioned whether American businesses and households would actually respond to higher fuel and energy prices. In doing so, Sen. Kerry overlooked the vast body of evidence quantifying price-elasticity in virtually every sector of the U.S. economy. He also had evidently forgotten what happened during the summer of 2008 when gasoline hit $4/gallon: traffic congestion eased, carpools, buses and trains filled up, and SUV sales tumbled. And that was only the short-term effect of a price spike; a long-term, predictable carbon emissions price increase would allow sound business planning and create incentives for long-term investment in energy efficiency and low-carbon alternatives.

And that points to a key reason that cap-and-trade is an inferior way to set a price on carbon: the price signal under a cap would be “noisy” due to both volatility and the fact that the price must be “revealed” through the market workings of the cap rather than being stated, explicitly, in the tax code. That noise means that with cap-and-trade it takes a higher price for the economy to “hear it” and respond, even if the general trend is upward.

Sen. Kerry is on solid ground relying on peer-reviewed climate science. But his ongoing misunderstanding of the workings of carbon pricing is almost as shocking as the AEI witness’s misrepresentation this week of climate science. It’s past time for both sides to get it right: The consequences of unmitigated climate change will be grave, whereas clear, simple, predictable carbon pricing is essential to catalyzing the solutions.

Photo: Flickr / The Minnesota Independent

The Three Newest Flaws in Cap-and-Trade

Democratic Senators Barbara Boxer (CA) and John Kerry (MA) are expected to introduce their long-awaited climate-change bill tomorrow. As the Houston Chronicle reported last weekend, the bill was delayed for months “by negotiations aimed at appeasing moderate Democrats worried that new emissions caps could impose hefty economic costs on the energy industry, struggling manufacturers and coal mining.”

The Boxer-Kerry bill is expected to be modeled after the Waxman-Markey bill that squeaked through the House in June. This means it will employ the cap-and-trade architecture that underpinned the 1997 Kyoto Accords and has been the cornerstone of the U.S. Big Green lobby’s legislative offensive on climate ever since.

[Addendum: The 821-page Boxer-Kerry “Clean Energy Jobs and American Power Act” was introduced Sept. 30. Go here for text, or here for section-by-section summary. — C.K., Oct. 1.]

Cap-and-trade has been attacked on many grounds: lack of a clear price signal, inherent complexity, and necessary reliance on trading mechanisms that would unleash a pandora’s box of financial machinations that could destabilize global finance. Of late, three new objections have surfaced against cap-and-trade as an “architecture” for reducing greenhouse gases. Each is worth considering as the Senate begins tackling climate legislation in earnest.

Outside NRDC's New York City headquarters, Sept. 24

The first concerns what has heretofore been billed as cap-and-trade’s greatest virtue: its foundation on a quantified emission target, i.e., a “cap.” Alas, the nature of a cap is to be fixed, and therefore not adaptable to changing circumstances — including, now, the sudden drop in U.S. emissions.

As everyone knows, the Great Recession has shrunk economic activity in the United States. And fossil fuel burning and CO2 emissions have been shrinking particularly fast. Consider just one sector, albeit a key one: coal-fired electric power generation.

Until very recently, coal-fired power plants were responsible for almost a third of all U.S. emissions of carbon dioxide. This year, however, the bottom has fallen out.

First-half 2009 figures released last week by the Energy Information Administration show an almost 13% drop in electricity generation from coal and an attendant 11% drop in the physical tonnage of coal burned to make power vis-à-vis the first half of 2008, as coal has absorbed the entire unprecedented 5% drop in overall electricity production. By my calculations, this six-month drop in coal burning alone has already translated to 106 million fewer metric tons of carbon dioxide, singlehandedly reducing total annual U.S. emissions by almost 2%. If continued through December, the 2009 decline in coal burning would cut U.S. emissions by 3% from 2005 levels, thereby achieving, in one sector, almost a fifth of the Waxman-Markey target of reducing 2020 emissions by 17%,

Yes, emissions will eventually “rebound” as economic recovery takes hold. But not all of the lost output will be made up. Moreover, some observers, The Earth Policy Institute’s Lester Brown among them, believe that much of the sudden drop in coal-fired and other emissions is due to emerging structural factors such as fuel-efficiency standards, the liftoff in renewable energy, and more widespread awareness of the perils of oil dependence. These developments too are cutting the Waxman-Markey 17% target down to size. While in theory this “stature gap” could be restored by writing a tougher target into the Senate bill, in practice it’s unlikely the bar will be raised this fall, or ever. If so, the vaunted “emissions certainty” in cap-and-trade will lock in a hollow achievement.

The second new flaw, variously referred to as the “voluntary reductions conundrum” or the “virtue dilemma,” concerns the prospect that under a cap-and-trade regime, any “extra” steps to reduce CO2 emissions stand to be canceled out by corresponding increases in emissions that the cap enables somewhere else. In effect, any action to, say, ride a bike instead of driving (or, on a larger scale, to create a bicycling infrastructure that can replace thousands of car trips), or to permit a wind-turbine farm whose output allows the grid to cut back on fossil-fuel generation, ends up creating “room” under the cap that lets other parties increase driving or coal-burning and emit the “saved” emissions.

The mechanism for this perverse consequence of a carbon cap would be a decrement in the auction price of allowances due to the increment in bicycling or wind output, encouraging a corresponding increment in driving or fossil-fuel power generation elsewhere within the capped entity. In effect, the celebrated cap in cap-and-trade dictates an emissions equilibrium that, in turn, vitiates any given decarbonizing measure which, absent the cap, would have reduced emissions.

The implication is troubling, to say the least. No more could one promote a proposed renewable-energy or energy-efficiency project as a climate-saver, if its fossil-fuel-saving virtue will be offset by an equal helping of fossil-fuel vice somewhere else. At the same time, a dirty-energy project (or failure to implement a clean one) could be justified on the grounds that the resulting propping up of allowance prices will enable other low-carbon investments or behaviors to come into being and pick up the slack. The idea that “the cap will provide” turns out, it seems, to be a two-edged sword.

The third and last cap-and-trade flaw attracting notice concerns transnational fungibility. Shorn of its recondite name, it denotes the difficulty if not impossibility of establishing a normative quantity-reduction target for greenhouse gases. In a nutshell, if the U.S. were to establish an emissions reduction goal of 17%, or any other number, for 2020 or any other future year, by what criterion should that target be deemed appropriate for any other country? After all, the United States emits twice as much CO2 per capita as comparably wealthy countries in Europe, and, of course, 5 to 20 times as much per person as China, India, Brazil, et al. (And this comparison doesn’t reflect the even greater disparities in historical or aggregate emissions.)

Needless to say, this problem of fungibility, or its lack, doesn’t apply to a carbon tax. A U.S. carbon tax of so many dollars per ton of CO2 might or might not be the “optimal” level, but it would at least translate fairly and equally across borders, disadvantaging manufacturers in every nation more or less equally. Moreover, as Elaine Kamarck has pointed out, many countries lack the administrative capacity to manage a cap-and-trade system, whereas most governments can at least collect taxes.

Nor would a carbon tax be beset by flaws #1 or #2. The impacts of a carbon tax on U.S. investment decisions, infrastructure provisions and personal behaviors will be relatively unaffected by aggregate contractions in emissions. Moreover, unlike cap-and-trade, a carbon tax won’t undercut virtue but will reinforce it, since each and every elimination of emissions will be rewarded by a corresponding reduction in the tax.

At this point, cap-and-trade seems to have little going for it other than institutional inertia. Let us hope that all of its drawbacks are closely and fairly scrutinized in the Senate debate now set to begin.

Photo: David Pine, rising tide north america

Senate Warned: Cap & trade Volatile, Offsets Ineffective

CTC Washington rep James Handley shares his notes from yesterday’s Senate Energy & Natural Resources Committee hearing on price volatility and cost containment for cap & trade:

I was encouraged. Many Committee members seem interested in working to make cap & trade more like a price mechanism via a “price collar.” “Revenue recycling” also came up. “Carbon tax” was discussed more than I’ve heard since the House Ways & Means hearings last spring. There was considerable candor and minimal posturing. My summary is a bit long, but the entire hearing was compelling and perhaps significant. I’ve bolded some of the highlights.

(Chairman) Sen. Bingaman: Price volatility as well as total cost, important concerns…

Sen. Murkowski: Climate is serious problem. Alaska witnesses. One reason Lieberman-Warner failed is that it didn’t control costs adequately.

Opening Statements:

Brent Yacobucci, Congressional Research Service: Price collar (floor & ceiling) most comprehensive way to control volatility and overall costs. Ceiling / safety valve is cash payment in lieu of buying allowances. RES passed by ENR does include “safety valve.” Lower limit, — reserve price. ACESA strategic reserve– not certain effective.

Eileen Claussen, Pew Center on Global Climate Change: Cap provides way for gov’t to set limit, business to meet limit with flexibility. Price of offsets and low carbon technology determine allowance price. EIA says if int’l offsets barred, would increase allowance price 65%. Low carbon tech– CCS and nukes would reduce climpliance costs. Multi-year banking provides “when” flexibility for redxns in cap/trade. Advantage of cap — slow economy carbon price drops– automatic adjustment. C-tax would require gov’t to intervene. Strategic reserve pool similar to price cap– w/o detracting from envt’l integrity.

Michael Wara, Stanford University (Law): Researched emissions trading, offsets under (UN, EU) CDM. Two conclusions: 1) offsets cannot provide cost control and environmental integrity. 2) price collar can provide both. Need durable program, thru 2050. CDM experience suggests that env’tl integrity [of offsets] difficult to measure. Establishing envt’l baseline — difficult. Hardest in heavily regulated sectors. E.g., China, energy sector already regulated, includes subsidies, regulations that already favor renewables and nat’l gas. Can’t determine if benefits are additional. Difficult to produce large enough quantity of credits/ offsets (to manage allowance price). ACESA 20 – 50 times larger than CDM and need higher envt’l integrity. ACESA dependent on offsets. Most redxns — offsets, rather than covered entities. Quantity certainty in doubt. (Price) collar = superior price control. Use $ from price collar to fund GHG reduction projects. Recommends collar instead of offsets.

Joseph Mason, Louisiana State University: Two approaches: quantity (cap/trade), price (carbon tax). Cap/trade assumes banking and borrowing can be optimized. But central banks’ experience with monetary policy shows that controlling money supply (or allowance supply) is very problematic. Bagehot’s rule: liquidity crisis addressed by “lending freely at a penalty rate.” Fed’s “discount window” for lending to banks not used much now. Similarly reserve requirements not used to control monetary policy. Tools for monetary control not well understood and can be gamed by speculators — might try to run up prices to game the bank. banking leads to hoarding, attempts to corner markets. Expiration dates on permits call to mind Zimbabwe’s currency which has expiration dates. Convoluted market design is un-necessary, carbon tax accomplishes directly. Borrowing institutional structures from one realm (monetary system) and applying to another (carbon trading system) rarely works. Tax achieves goal of price certainty.

Jason Grumet – Bipartisan Policy Center: Support price collar, strategic reserve and aggressive oversight of market. Tremendous uncertainty — offsets. 1 billion very unlikely to be available.

Q/A:

Sen. Bingaman: Int’l forestry projects — need to fund. Offsets?

Wara: Need 1) objective baselines, quantify offsets, 2) solidify property rights in develping countries. W/o certainty of prop ownership, more uncertainty about land use. Major developing co’s — delicate issue = land titles.

Grumet: largest source of int’l offsets = forestry. but not avail next 12 – 36 mos.

Claussen: Real possibility, US engage in int’l forestry regime.

Bingaman: EU not recognizing foresty offsets b/c no baseline. Domestic offsets?

Wara: Ag offsets very difficult to do well. Already have programs for tillage. Can monitor smokestack. Field isn’t smokestack. Soil varies, history varies, water, weather… many quantification problems.

Sen. Murkowski: House bill relies so heavily on offsets. People at home scratching heads. How does it work? Rob’t Shapiro (former Clinton Admin) says “trillion dollar mkt securitized by Wall St.” How avoid? Carbon Tax?

Mason: to stabilize prices, (carbon) tax avoids problems. Offset verification, similar problems to mortgage verification. reckless to go into new market. Prop rts critical. must be stable to sell meaningful offset. Developing co’s have political instability. Big investment in offsets could lead to another bailout. Parties (buyer and seller) have incentive to overstate value, game system.

Grumet: Bipartisan carbon tax proposal would gain steam if someone would propose. short of that, collar = elegant solution. reduces potential for malfeasance.

Sen. Cantwell: Mason’s testimony is “music to my ears”. Specificity in EU. Enron needed “the tape” of “get grandma” to trigger investigation. Now see problem in EU. System inherently favors special interests. Predictability = different way.

Mason: Insulate mkts from those w/ overt interests. In Britain, speculators intervened to push strategic reserves. Tax doesn’t need to be set to internalize all costs. Even nominal “user fee” encourages some behavior change. Might get 80% of benefit with moderate price. Can do today.

Sen. Cantwell: Benefit of floor?

Grumet: Wall St / spec interests. but also want to stimulate innovators. floor reduces price uncertainty– now investors must assume zero carbon price. $10 could do a lot.

Wara: Floor means (green energy) investors can go to bank and borrow. EU — downside risk actually greater than hi prices.

Sen. Corker: Rube Goldberg notion – vehicle. price volatility. Why don’t climate chg advocates level and say we need higher C price? floor would reward investors. Why not tax? (I restrained my impulse to applaud.)

Claussen: Would support carbon price / tax if high enough to get redxns. Offsets are low cost reductions.

Sen. Corker: Isn’t a tax a better approach? Aren’t int’l offsets just wealth transfer abroad? Why not recycle revenue into our economy?

Wara: “Vast majority” of reductions would be offsets (under ACESA).

Sen. Corker: Safety valve + price floor, in essence carbon tax. Wish public could hear all this.

Sen. Shaheen: Not sure public should hear. Public would be concerned. how set prices? Market? How do cap and limit prices w/o interfering in market?

Grumet: “Interference” with volatility is salutory. Set floor at $13 – 15 and ceiling at 2x, eg $28 would get redxns. $20 price makes electric convert. $25- 30 sustained.

Claussen: support price floor (but not ceiling). Hard cap, too high. strategic reserve better than price ceiling.

Sen. Shaheen: how set floor?

Grument: price needs to support technol investors. clarity that there will be a price would help a lot. eg $10 floor rising 5 – 10% would be very meaningful. if too low, lose potential to encourage innovation. rate (eg $8 vs 15) is political decision, but certainty is very imp’t.

Mason: Price is zero now. dithering– waste time, investment. Objects to cap/trade because of well identified externality problem. do not know what right amount of carbon is. (unlike acid rain.) could start with modest carbon tax, and later change to quantity-based system.

Sen. Stabenow: quantify Ag offsets. Sec’y of Ag doing great job. Price collar– agree floor and ceiling. also support offsets. Wara — critical of offsets. “Smart design choices” eg re deforestation. Would you eliminate offsets? CBO found that w/ offsets, allowance price in 2030 ~ $40/T. w/o offsets, $138/T. Share Corker’s observation — int’l offsets– want reductions where “ton of carbon = ton of carbon.” Offsets vs Collar?

Wara: Both design, better than offsets alone. mulitple parties favor cheap offsets. Buyer and seller. regulators have wide discretion. pressure to create credits. favor creation over integrity. Price collar improves integrity of offsets– greater incentives to regulate effectively.

Grumet: Need both. But concern re offsets as (sole) containment. Pressure, low qual offsets. undermined if collar, not unlimited offsets.

Sen. Barrasso (R-Wyo): concern Wall St gaming. cap/ tax green collar crime. abuse, UK suspended energy auditor (Guardian article). SGS suspended 2d company suspended. Another Enron situation?

Wara: SGS suspension = positive step. previously auditors impunity. need incentives for auditors. adequate, no. but improvement, yes.

Mason: pattern familiar financial crisis. 1400 pages (ACESA) lots of places for influence and holes. too little environmental effect for too much cost. Chicago climate exchange hired lobbyists – want lax rules for trading, offsets, early action credits, don’t want limits on who can trade. banks supply credits for allowances.

Sen. Dorgan: day trading oil very volatile. collar discussion. lack of confidence in mkt. not support $1 trillion new mkt. diminishing product year by year. “rolling seas of cap & trade” set price. estimate size of market and range of volatility?

Mason: $1 trillion is under-estimate. volatility — hard to see mkt w/o volatility. if we don’t like volatility, we shouldn’t choose market to set price. will bail out when price goes up (?) energy cos can trade, arbitrage opp’ys.

Sen. Dorgan: derivatives / swaps have already in EU. new products. hang US growth on this? prefer “carbon fee”?

Grumet: since BTU tax, don’t say “tax”. if serious about problem, then support carbon tax. if not, have to fix market.

Sen. Dorgan: regulation of markets, pathetic.

Grumet: collar is training wheels for mkt. balance mkt.

Sen. Dorgan: need to talk about all alternatives– regulation and carbon tax as well as cap/trade.

Sen. Bennett: conclusion of Mason (p 20) “hinging econ growth on complex contract and market design both of which have yet to be tested in the real world”. Any cost / benefit on cap/trade, or carbon tax or command/control?

Wara: NYU law school did cost/benefit analysis of cap/trade and found very positive.

Clausssen: lost of analysis re costs but few on benefits. but believe benefits far exceed costs.

Yacobucci: range of benefit is very wide.

Sen. Bennett: Temp redxns– wide “delta” — impact on Temp de minimis.

Grumet: Must assume US is leading world. same as any big problem, hunger, poverty, war… price collarwould avoid underminining econ strength. then support taking 2d and 3d steps.

Sen. Bennett: problem– US leads but no one follows, then stuck with program.

Claussen: w/o US action, no world action. if we do act, then (others actions) depend….

Sen. Bennett: Visited EU. $20/T trading. advice they gave– “go slow, start small.”

Sen. Bingaman: “Well we’re certainly following that advice.” (laughter)

Sen. Murkowski: cost concern. mechanism to recognize recession?

Grumet: econ has changed discsn. if pass law now, effective maybe 2014. recession will be past. uncertainty in carbon mkts is deterring investment now.

Wara: Health care analogy apt. existing system — EPA will regulate under CAA. not as if nothing there. do nothing is not an alternative. EPA proceeding.

Sen. Cantwell: transition– EPA estimates $1.4 trillion int’l offsets under ACESA. What could we buy here with that?

Wara: EPA unrealistic. low cost offsets. presumes $1 billion T/yr. Thinks will be much smaller.

Mason: property laws. change rules. no property tax, owners sit on land and don’t use. immediate benefits from carbon price. US shipping pelletized wood to EU for offsets. Where does that make sense?

Sen. Corker: not enough offsets? assuredly “enough hucksters” to sell trillion $ figure. way to benefit taxpayers– rev-n carbon tax, no $$ leaving economy.

Grumet: right goal exactly. challenge– how to give back equitably. (ACESA) efforts to divert allowances to utilities, state regs on utilities — rev’s to ratepayers. cap / dividend?

Mason: Markets — no boundaries. Taxes do (have boundaries).

Wara: distn of revenue. complicated. firms have some (legit) claims. households also. taxes theoretically better. but not necessarily simple. want single rate. hard to do in real world. EU– not simple. $ for adaptation. tax scheme will want exemptions. should explore tax but won’t be simple.

Sen. Corker: Ancillary goal of cap/trade. takle in $ then spend $6 trillion in last year.

Sen. Bennett: “Trust fund” / ear mark defeats appropriations discretion. EU covers utilities not automobiles. why? they only have accurate data on utilities. Saw big pickup truck with sticker “this truck is offset by… ” XYZ website. Real? Accurate data?

Claussen: EU over-allocated. system failed. now have data.

Wara: US EPA doing inventory— reporting GHG emissions. EU mobile sources already taxed. Germany equivalent to $220/T. states regulate at refinery. RAC [Refiner Acquisition Cost & volume of crude oil, reported to EIA] = good data. at pickup truck — not good data.

(Some) Carbon Tax Advocates Are Serious

CTC rep James Handley’s comment on columnist Eric Pooley’s recent piece “Exxon Works Up New Recipe for Frying the Planet” (Bloomberg) sparked this illuminating, constructive exchange.

Dear Mr. Pooley,

Thanks for your article. Climate crisis deniers are indeed doing great harm. Are they really changing tactics from bogus science to bogus economics or just using both? I was with you until I read this:

“A tax wouldn’t guarantee any carbon reductions, let alone bring about the steep cuts needed to stave off the worst climate changes.”

If you’re suggesting that a cap would “guarantee” emissions reductions in some way that a tax would not, I must disagree.

Consider economist Alan Viard’s Aug. 4 testimony to the Senate Finance Committee:

If the market price of allowances under cap and trade is $20 per ton, every firm has an incentive to take any step that can reduce emissions at a cost of less than $20 per ton, but no incentive to take any step that reduces emissions at greater cost… precisely the incentive that each firm would face if it were subject to a carbon tax of $20 per ton or if it were subject to a cap-and-trade program (with the same $20 allowance price) in which all allowances were auctioned.

… The difference, of course, is that the carbon tax or the auction would raise government revenue equal to the aggregate value of the allowances. If the allowances are freely allocated, then that value instead accrues to firms. Cap and trade with free allocation is equivalent to a carbon tax with transfer payments to firms.” [Emphasis added.]

I work with the Carbon Tax Center because, along with most  economists who’ve considered the question, I’m convinced that a clear, transparent, gradually-increasing price on carbon pollution is essential to spur energy conservation as well as development and implementation of alternatives to fossil fuels. A carbon tax, with revenue recycled directly to households to build political support and mitigate the economic impacts of what portends to be a decades-long trek to a low carbon economy, offers a real “game changer” to move broadly enough to substantially mitigate climate catastrophe.

economists who’ve considered the question, I’m convinced that a clear, transparent, gradually-increasing price on carbon pollution is essential to spur energy conservation as well as development and implementation of alternatives to fossil fuels. A carbon tax, with revenue recycled directly to households to build political support and mitigate the economic impacts of what portends to be a decades-long trek to a low carbon economy, offers a real “game changer” to move broadly enough to substantially mitigate climate catastrophe.

British Columbia has shown that a revenue-neutral carbon tax can be implemented in a few months and gain public support. And it’s far more effective than trading in carbon allowances, especially with offsets. Price volatility has prevented the EU’s cap-and-trade from spurring investment in alternative energy and conservation. See e.g., EU Cap-and-Trade System Provides Cautionary Tale (Roll Call).

The enemy of my enemy isn’t necessarily my friend. Climate crisis deniers’ opposition to cap-and-trade doesn’t make it a good idea. And the “endorsement” of a carbon tax by (former?) deniers can obscure the fact that a growing environmental and social justice coalition is advocating a carbon tax with revenue-recycled to households. Please don’t help the “deniers” poison the water for the most effective, transparent climate policy.

– James Handley, Carbon Tax Center

———-

James,

Thank you for your very thoughtful note. A full treatment of the cap v. tax debate was beyond the scope of the column, but I didn’t mean to suggest that a well -designed tax would be unworkable, rather that any tax Exxon would support is likely to be ineffective.

My basic concern here is political rather than economic– that the carbon tax will siphon enough support to derail cap and trade, but not enough to pass, and we will be left with nothing. I tend to agree with Al Gore when he points out that the nations that have been most effective in reducing emissions have both a cap-and-trade program and a carbon tax in place; ultimately we are likely to need both as well, but that’s a ways off. In the meantime, as Gore has said, “a cap-and-trade system is also essential and actually offers a better prospect for a global agreement, in part because it is difficult to imagine a harmonized global CO2 tax.” The fact is, cap and trade is the only climate program that has a chance of passing now. There’s a big game going on inside the stadium, but the carbon tax proponents are outside in the parking lot, dreaming about next year.

I don’t think cap and trade is (as many tax proponents have argued) a faintly disreputable cousin to the tax which no one would welcome if the tax itself were passable now. I think the cap has real advantages, which I’ll get to. I understand the longing for a simpler approach to the problem but have my suspicions about the simplicity argument; a tax bill would have to respond to the same legitimate regional and sector cost issues that complicated Waxman-Markey, so a bill that could pass would not be simple. How for instance would the straight per capita tax rebate or payroll offset I often see proposed deal with the higher cost burden in coal-dependent states? Staffers on the Hill tell me that adjusting the tax every few years would require a new Act of Congress every few years — it’s hard enough to get this done once.

The free allowance formula devised by EEI and incorporated in Waxman-Markey, by taking into account carbon intensity, isn’t perfect but does a good job of responding to the regional disparity issue. And since the bill requires LDCs [local (electric) distribution companies] to pass on the value of all allowances to their ratepayers, it would prevent the LDCs from enjoying windfalls. Alan Viard’s testimony ignores this requirement when it claims that the value of free allowances accrues to firms. That’s not how the bill works—it’s one of many misconceptions about Waxman-Markey. Overall I’m impressed with the way Waxman et al. learned from the mistakes in the EU ETS. Over-allocation and lack of baseline data were the biggest drivers of volatility there, and this program would avoid those. Nor would utilities be able to charge opportunity costs to their ratepayers, as EU generators did. Giving the transitional allowances to LDCs instead of generators solves other problems as well. It sends a clean price signal to the generators while cushioning ratepayers.

As for the ‘guarantee,’ of course there is no magic wand. But the cap is more than a price signal. We do have the technology to monitor and verify reductions, and I want to see that framework put in place as soon as possible. Finally, no one seems to talk about the penalties for busting the cap, which under Waxman-Markey amount to 2x the allowance price plus a replacement allowance, or three times to compliance incentive — under your $20/ton comparison, the compliance incentive for the cap is actually $60 per allowance, vs. $20 for the tax, plus the strong market signal driven by the knowledge that the cap is ratcheting down over time. The aggressive 2030 reduction target in Waxman-Markey — 42% below 2005 levels —has not received the attention it deserves. It would transform the energy investment decisions of American businesses.

Thanks again for your email and for your work at the Carbon Tax Center. I really would welcome either a tax or a cap. But at the risk of turning your words against you, let me suggest, as someone who has been watching this debate unfold, that it is the carbon tax advocates who have at times been poisoning the water against the cap. Probably both sides have been guilty of this, but it’s too bad that the climate action community is divided at the very moment unity is so badly needed.

– Eric Pooley

———-

Eric,

Thanks for your reply. I think we’re in strong agreement on most points. I want to respond to three:

1) You wrote: “My basic concern here is political rather than economic– that the carbon tax will siphon enough support to derail cap and trade, but not enough to pass, and we will be left with nothing…”

Fortunately, it’s not ACESA or nothing. Although, given that ACESA’s attempted domestic emissions reductions are so modest, and that its cap-and-trade system would entrench Wall Street traders and purveyors of offsets and set the stage for another financial crisis, I’d probably opt for nothing.

If ACESA fails to pass, EPA can continue to develop a regulatory system under the Clean Air Act, which the Center for Biological Diversity has concluded could be quite comprehensive (and might include a cap-and-trade system). This is likely to be better than ACESA in several key ways. For instance, I gleaned from EPA’s Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking last year that its rule would not include offsets. (Can you imagine EPA trying to justify the up to 1.5 billion tons of international offsets — essentially, transfer payments — that make a mockery of the notion of a “hard cap” in ACESA?) Furthermore, ACESA as passed by the full House would eviscerate EPA’s proposal to account for indirect impacts of biofuels (e.g., forest clearing to grow corn for ethanol).

Because the Clean Air Act covers stationary sources, mobile sources and the content of fuels, the scope of an EPA GHG reduction program can be very broad. President Obama’s representatives could go to Copenhagen with an EPA draft rule in hand, pointing out that the U.S. is in the process of regulating (or “capping”) more of its GHG sources than any other industrialized nation. That’s far from the most effective policy (a revenue-neutral carbon tax) but it’s also a long way from “nothing.”

2) You quote Al Gore “…a cap-and-trade system is also essential and actually offers a better prospect for a global agreement, in part because it is difficult to imagine a harmonized global CO2 tax.”

Gore’s got it backwards. As the Congressional Budget’s report, “Policy Options for Reduction of CO2 Emissions,” explains, if nations choose different carbon tax rates (or fail to enact them) WTO authorizes border adjustments to equalize tax rates on imported products to the same levels applied to similar domestically-produced products. In effect, the U.S. would collect the carbon tax on imports from any country that didn’t enact its own, providing a powerful incentive for our trading partners to follow our lead.

In contrast, under cap-and-trade, harmonization would require determining the implicit carbon price in a system where carbon prices are hidden and fluctuating. The CBO observed, “Linking cap-and-trade programs would… entail additional challenges beyond those associated with harmonizing a tax on CO2.” The report noted, for example, that linked cap-and-trade programs tend to create perverse incentives for countries to choose less stringent caps so they could become net suppliers of low-cost allowances.

Moreover, as Elaine Kamarck of Harvard’s Kennedy School has pointed out, almost every nation has a tax collection mechanism that could be used to administer a carbon tax, but few (if any) have the means to enact and enforce a complex cap-and-trade system. If we’re going for a global carbon reduction system, it’s a carbon tax.

3) You wrote: “…a tax bill would have to respond to the same legitimate regional and sector cost issues that complicated Waxman-Markey, so a bill that could pass would not be simple… adjusting the tax every few years would require a new Act of Congress every few years — it’s hard enough to get this done once.”

The complexity (and length) of Waxman-Markey seems to have much more to do with preserving (and even expanding) the coal industry than with addressing regional disparities in household income caused by carbon pricing, which, in fact, are relatively small. (See our summary: Regional Disparities.)

Economist Dallas Burtraw (Resources for the Future) studied the regional “incidence” of carbon pricing and concluded that regional differences are dwarfed by very large disparities across the income spectrum. CTC’s proposed carbon tax shift would more than compensate for the inherent regressivity of a carbon tax by distributing revenue progressively either through a payroll tax cut (as proposed in legislation introduced by Rep. John Larson) or a direct, equal distribution. Waxman-Markey only attempts to compensate the lowest income group, leaving middle income households to shoulder the burden of carbon pricing. (Burtraw and others have also shown that ACESA’s free allowances to LDCs would mostly benefit commercial, not residential electricity users.)

We recognize that some regional adjustment might also be needed; but that’s a relatively simple proposition under a carbon tax and could be done administratively, without the need for legislation. Rep. Larson’s bill provides for automatic increases in the carbon tax level to ensure that the trajectory of emissions reductions is in line with the scientific consensus.

Thanks again,

James

———-

James,

I think you’re kidding yourself about the EPA’s ability to impose cap-and-trade under CAA. Someone who knows a lot more about politics than either of us, former White House Chief of Staff John Podesta, has said it would be difficult for EPA to do so without Congressional assistance. Protracted litigation would see to it that years went by before such a system came into force. And there is no chance that an administration promise of such rulemaking – which any subsequent administration could undo – could form the basis of a treaty.

Dallas Burtraw is a fine economist, but the many Senators and members of Congress I have been talking to all summer simply do not agree with him. Regional and sectoral disparities are the single biggest obstacle to climate action, and lawmakers do not believe that the “simple carbon tax” solves them. That’s why Rep. Mike Doyle of Pennsylvania backed Waxman-Markey instead of John Larson’s carbon tax. It’s one of the reasons Waxman-Markey passed the House and Larson’s bill didn’t make it to markup. If the politics were reversed and a carbon tax had a shot at passing, I would expect cap-and-traders to get behind the carbon tax and push hard. But right now, it is the cap that has a real chance of passage, and it could be years before the next opportunity presents itself. Please don’t let your strong shoulders go to waste.

– Eric

———-

Eric,

Regional and income disparities arise under either a carbon tax or cap-and-trade (in fact, Burtraw considered it the same problem), but it’s easier to mitigate these regional and income disparities under a transparent carbon tax by directly distributing the revenues to households.

Rep. Larson and the other members of the Ways and Means Committee, which held a series of very illuminating hearings last spring about the very serious volatility and gaming with cap-and-trade, didn’t get a shot at climate legislation because the House leadership didn’t permit amendments – they didn’t want any discussion of alternatives to cap-and-trade.

I agree with economist Robert Shapiro (Clinton undersecretary of Commerce and U.S. Climate Task Force co-chair) who said at our July 13 Senate briefing that ACESA deserves to be defeated. He fears that, as in the E.U., cap-and-trade would fail to reduce emissions and would delay needed reductions by a decade or more. I cannot support a hidden, volatile and regressive carbon tax (set and collected by Wall Street) whose main advantages seem to be that it hides the price and is called “cap-and-trade”. I believe an explicit, predictable and progressive carbon tax with revenue recycled to households is essential. British Columbia’s experience shows that a revenue-neutral carbon tax is politically feasible. But, to return to my original point, first we need to get beyond magical thinking about “caps”.

– James

photo: Flickr / random dude

Media Buzz Intensifies Ahead of Carbon Tax Hill Briefing

The Carbon Tax Center’s Capitol Hill briefing is just two days away (Dec. 9), and we couldn’t have choreographed a more turbocharged buildup than the one provided over the past few days by The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal.

Thomas Friedman’s column in today’s Times, The Real Generation X, is his most full-throated call ever

for a carbon tax. It’s a welcome return to his earlier editorializing in favor of carbon taxing from his recent slight tilt toward cap-and-trade (emphases added):

It makes no sense to spend money on green infrastructure — or a bailout of Detroit aimed at stimulating production of more fuel-efficient cars — if it is not combined with a tax on carbon that would actually change consumer buying behavior.

Many people will tell Mr. Obama that taxing carbon or gasoline now is a