Car and Driver: Plummeting Auto Sales Show Value Of Putting A Price On carbon (Wash. Post editorial)

Frustrated Owners Try to Unload Gas Guzzlers (Boston Globe)

Frustrated Owners Try to Unload Gas Guzzlers (Boston Globe)

Indiana and North Carolina Voters Reject Gas Tax Holiday, Open Door to Consideration of Revenue-Neutral Carbon Tax

CARBON TAX CENTER

PRESS RELEASE

Press contacts:

Daniel Rosenblum, Co-Director • 914-837-3956 • dan@carbontax.org

Charles Komanoff, Co-Director • 212-260-5237 • kea@igc.org

OPEN DOOR TO CONSIDERATION OF REVENUE-NEUTRAL CARBON TAX

NEW YORK (May 7, 2008)

Voters yesterday rejected Senator Hillary Clinton’s proposed gas tax “holiday” and, with it, the idea that energy taxes are political poison. The resounding victory in North Carolina and unexpectedly strong showing in Indiana by Senator Barack Obama, the only presidential candidate to oppose the Clinton-McCain tax holiday, could open the door to consideration of a revenue-neutral carbon tax.

While not every election serves as a referendum on a particular policy issue, yesterday’s clearly did. The proposal to suspend the federal gasoline tax this summer was the major policy issue distinguishing Senator Clinton from Senator Obama between the April 22 Pennsylvania primary and today. The issue received extensive media coverage due to both senators’ focus on it amid widespread concern over gasoline prices. [Update – As the New York Times noted this morning, "In both states, the candidates’ final arguments centered on a summertime suspension of the federal gasoline tax, which Mrs. Clinton proposed as an economic lift for voters and Mr. Obama derided as a political gimmick."] In rebuffing Senator Clinton’s quick and simplistic fix, voters demonstrated that they will consent to a tax when it advances important economic, environmental and national security priorities.

“Voters sent a powerful message yesterday that they are not willing to sacrifice the environmental and economic benefits of the gasoline tax for trivial, short-term benefits,” said Daniel Rosenblum, co-director of the Carbon Tax Center. “Voters in Indiana and North Carolina have driven a spike through the conventional wisdom that supporting a tax is political suicide. The path is cleared for consideration of a revenue-neutral carbon tax-and-dividend approach that cost-effectively reduces greenhouse gas emissions, strengthens the economy, reduces America’s dangerous dependence on foreign oil and returns the tax proceeds to all Americans through monthly dividends,” Rosenblum said.

“Voters sent a powerful message yesterday that they are not willing to sacrifice the environmental and economic benefits of the gasoline tax for trivial, short-term benefits,” said Daniel Rosenblum, co-director of the Carbon Tax Center. “Voters in Indiana and North Carolina have driven a spike through the conventional wisdom that supporting a tax is political suicide. The path is cleared for consideration of a revenue-neutral carbon tax-and-dividend approach that cost-effectively reduces greenhouse gas emissions, strengthens the economy, reduces America’s dangerous dependence on foreign oil and returns the tax proceeds to all Americans through monthly dividends,” Rosenblum said.

“These past few weeks, Sen. Obama has stood up for energy prices that tell the truth about climate damage and national insecurity,” said Charles Komanoff, co-director of the Carbon Tax Center. “The voters have rewarded Obama’s political courage and sent a clear signal to Washington that they support price incentives to conserve oil and curb carbon emissions,” Komanoff added.

As Senator Obama stated in his North Carolina victory speech last night, “the American people are not looking for more spin. They’re looking for honest answers to the challenges we face.” An honest answer to the climate change challenge includes truth in energy pricing.

The Carbon Tax Center is a non-profit educational organization launched in 2007 to give voice to Americans who believe that taxing emissions of carbon dioxide — the primary greenhouse gas — is imperative to reduce global warming. Co-founders Charles Komanoff and Daniel Rosenblum bring to CTC a combined six decades of experience in economics, law, public policy and social change.

———————————–

Photo: Flickr/cecily7.

The Gas Tax and the Un-Tax

Guest Post by James Handley

Will you sell your vote for $25? Presidential candidates John McCain and Hillary Clinton are betting you will. They’re campaigning for a “holiday” on federal gasoline taxes for the summer months.

Of the three presidential contenders, only Barack Obama has demurred. Obama said last week:

[T]he federal gas tax is about 5 percent of your gas bill. If it lasts for three months, you’re going to save about $25 or $30, or a half a tank of gas.

Obama insists that the only permanent solution to rising gasoline and diesel fuel prices is to reduce consumption and increase use of alternative fuels.

Haven’t we been down this road before? Yes, a dozen years ago. The New York Times excoriated the same “gas tax holiday” in May 1996:

Haven’t we been down this road before? Yes, a dozen years ago. The New York Times excoriated the same “gas tax holiday” in May 1996:

Fill ‘er up, America, this is the Memorial Day holiday and the start of the “summer driving season.” We are a road-running, gas-guzzling people and Bob Dole, Newt Gingrich and Bill Clinton all say our Federal tax should be lowered 4.3 cents a gallon. But the tax relief, if it ever comes, will be trivial — and will have a negative impact on public policy. It is, in short, something of a political fraud.

Low prices and higher demand by consumers, many of them all too willing to pay any price to drive at and over higher state speed limits, will only increase American dependency on foreign oil. If people are worried about energy, not to mention the environment and the budget deficit, suspending the 1993 gasoline tax increase (many politicians would make it permanent next year) is exactly the wrong way to go.

Now the specter of catastrophic global warming is snapping into sharp focus like a jack-knifed tractor trailer blocking all lanes as we careen along at 75 mph. Sirens are wailing and lights are flashing thanks in large part to the Nobel-winning work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and Dr. James Hansen’s NASA-Goddard Climate team, un-muzzled despite Bush Administration threats.

And yet, U.S. energy policy is still “pedal to the metal” on the global warming accelerator — with McCain and Clinton urging us to “step on it” with a gas tax break. The exact opposite of what economists say is the essential step: pricing carbon emissions.

Yale economics professor William Nordhaus offers this litmus test:

[W]hether someone is serious about tackling… global warming can readily be gauged by… what they say about the carbon price. Suppose you hear a public figure who speaks eloquently of the perils of global warming… propose regulating the fuel efficiency of cars, or requiring high efficiency light bulbs or subsidizing ethanol, or providing research for solar power — but nowhere mentions the need to raise the price of carbon.

You should conclude that the proposal is not really serious and does not recognize the central economic message about how to slow climate change. To a first approximation, raising the price of carbon is a necessary and sufficient step for tackling global warming. The rest is largely fluff.

By declining to dangle the $25 bribe before the electorate, Sen. Obama has avoided the fluff. But he hasn’t yet taken the pro-active step of using prices to put the U.S. economy on a low-carbon diet.

Nordhaus provides the intellectual model, explaining that taxes on “bads” such as pollution and waste make our economy more productive and efficient and should therefore be viewed as the opposite of taxes on “goods” like products, income and employment.

Seven-Up soft drink was advertised in the ‘70s as the “Un-Cola.” Perhaps it’s time to market a carbon tax as the “un-tax.”

Photo: Flickr / pbo31

U.S. Gasoline Demand Dropping (Finally!)

On the same day that real crude oil prices broke a 28-year record, the Wall Street Journal heralded a long-awaited drop in U.S. gasoline consumption.

The Journal’s lead story today, Americans Start to Curb Their Thirst for Gasoline, was a powerful rebuttal of the notion that gasoline use is inelastic, and a vote of confidence in carbon tax advocates who have insisted that rising fuel prices will dampen energy demand.

Here are excerpts from the Wall Street Journal story, spiced with our commentary.

Here are excerpts from the Wall Street Journal story, spiced with our commentary.

As crude-oil prices climb to historic highs, steep gasoline prices and the weak economy are beginning to curb Americans’ gas-guzzling ways.

In the past six weeks, the nation’s gasoline consumption has fallen by an average 1.1% from year-earlier levels, according to weekly government data.

That’s the most sustained drop in demand in at least 16 years, except for the declines that followed Hurricane Katrina in 2005, which temporarily knocked out a big chunk of the U.S. gasoline supply system.

This time, however, there is evidence that Americans are changing their driving habits and lifestyles in ways that could lead to a long-term slowdown in their gasoline consumption.

Economists and policy makers have puzzled for years over what it would take to curb Americans’ ravenous appetite for fossil fuels. Now they appear to be getting an answer: sustained pain.

Of course, unlike the pain of "market-driven" high prices, the pain of socially mandated carbon pricing would be offset by rebating the revenue or tax-shifting.

Over the past five years, the climb in gasoline prices, driven largely by the run-up in crude oil, hardly seemed to dent the nation’s growing thirst for the fuel.

Conventional thinking held that consumption would begin to taper off when gasoline hit $3 a gallon.

But $3 came and went in September 2005, and gasoline demand didn’t flinch. Consumers complained about the cost of filling their tanks, pinched pennies by shopping at Wal-Mart, and kept driving.

Economists who study the effects of gasoline prices on demand say consumers tend to look at short-term price spikes as an anomaly, and don’t do much to change their habits. They might spend less elsewhere to compensate, or take short-term

conservation measures they can easily reverse, such as driving slower or taking public transportation, but the impact is minimal.Regular gasoline prices jumped to $2.34 a gallon at the end of 2006, up 62% from 2003, according to the EIA. Yet demand continued to grow at an average 1.1% a year. Consumers were better able to absorb the increase because it was spread over

four years, and the economy was doing fairly well.

Then again, annual demand growth of just 1% while the economy was expanding at 3% was strong evidence of at least some short-run price-elasticity.

Today, a weakening economy is intensifying the effects of high gasoline prices… The combination of forces is prompting Americans to cut back on driving, sometimes taking public transportation instead. It’s also setting the stage for what may be a long-term slowdown in gasoline demand by forcing Americans to become more fuel-efficient faster.

"If you think about the fact that U.S. motorists are responsible for one out of nine barrels of oil consumed in the world…and that consumption is no longer growing the way it used to, that’s a major structural change in the market," says Adam Robinson, analyst with Lehman Brothers.

The longer gasoline prices remain high, the greater the potential consumer response. A 10% rise in gasoline prices reduces consumption by just 0.6% in the short term, but it can cut demand by about 4% if sustained over 15 or so years, according to studies compiled by the Congressional Budget Office.

The implied 0.4 long-run price-elasticity noted above is precisely the level we (CTC) assume in our 4-sector carbon tax impact model, which may be downloaded here.

As consumers make major spending decisions, such as where to live and what kind of vehicle to drive, they are beginning to factor in the cost of fuel. Some are choosing smaller cars or hybrids, or are moving closer to their jobs to cut down on driving. Those changes effectively lock in lower gasoline consumption rates for the future, regardless of the state of the economy or the level of

gasoline prices.Anne Heedt, of Clovis, Calif., has been moving toward a more fuel-efficient lifestyle for the past few years. She owns a Toyota Prius hybrid but takes her bike on errands when weather permits.

"We’re not always going to have the same accessibility to gasoline that we’ve had in past decades, so we do have to start thinking about what we’re going to do over the next 50 years," said the 31-year-old Ms. Heedt, who used to work at a

medical office but is between jobs.

Way to go, Anne. You should be CTC’s poster child!

The housing boom encouraged the development of far-flung suburbs, contributing to longer commutes. Now developers are building more walkable neighborhoods close to city centers and public transit, and Americans are beginning to migrate back toward their workplaces, city planners and other experts say.

David Hopper, who lives in the rural community of Markleville, Ind., is preparing to move to a new house in Plainfield, cutting his commute to Indianapolis to 15 miles from 47 miles. Mr. Hopper decided to move closer to the city last summer, when gas prices hit

$3.40 a gallon in his area.

Together, Anne’s and David’s examples suggest the broad range of ways in which individuals respond to carbon-pricing signals. It’s heartening to see this reporting in a major paper like the Journal.

Pinched consumers also are speeding up their shift to more fuel-efficient cars. Sales of large cars dropped by 2.6% in 2006 and by 10.5% in 2007. In January, they plummeted 26.5% from a year earlier, according to Autodata Corp.

Car dealers are selling fewer minivans and large sport-utility vehicles. In fact, only small cars and smaller, more fuel-efficient SUVs, are showing a rise in sales. Small-car sales in January were up 6.5% from a year earlier, while sales of crossover vehicle grew 15.1%, Autodata Corp. says.

These trends evidently deepened in February. The New York Times reports that sales of SUV’s and pickups in the U.S. fell 14% last month, vs. a 5% drop in car sales.

Music to our ears. Meanwhile, the The Times is reporting that crude oil prices finally surpassed the historical inflation-adjusted peak from April 1980. How sad for Americans that the record-high price includes fabulous "rents" for oil owners and extractors. How much better instead to tax carbon fuels and re-allocate the revenues to American families.

Photo: bicyclesonly / Flickr

Clean Coal Hopes Flicker?

Assuming there really is such a thing as "clean coal," its future is looking increasingly bleak, according to After Washington Pulls Plug on FutureGen, Clean Coal Hopes Flicker in today’s Wall Street Journal. The WSJ describes the impact of DOE Secretary Samuel Bodman’s Jan. 30 decision "yanking its support for the project, whose price tag had ballooned to $1.8 billion, nearly double original estimates." The WSJ adds, "the nation could face supply shortages in coming years unlike anything seen in the past" without new coal plants and if "nuclear power also stumbles."

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid had a somewhat different perspective last week. As reported in Platts, Senator Reid stated that, "I think the coal companies should be upfront with the American people that coal is one of the things that is ruining our world." Reid added:

The coal industry around the country is spending tens of millions of dollars to give false and misleading information to people around the country saying ‘all we want to do is have clean coal. Why won’t they let us do the clean coal’…My answer to that is that is doesn’t exist. There is no clean coal technology. There’s cleaner coal, there’s no clean coal technology.

Senator Reid doesn’t expect zero-emissions coal fired generation to be available for another twenty years and says we should "just back off" and look to cleaner energy sources like natural gas and renewables.

The key lesson of the FutureGen story, as well as past government attempts to pick winners (such as synfuels during the Carter and Reagan administrations), is the need to internalize the costs of CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels in the price of energy via a carbon tax. With a carbon price, consumers and power producers could make rational economic choices to use less energy and substitute less carbon-intensive fuels for coal. Coal would lose its artificial competitive advantage, the economics of renewable energy would improve dramatically, and even more energy efficiency would become cost-effective. Who knows, even zero-emissions coal might become available — eventually.

Photo: Zach K / flickr

Is Google Betting on a Carbon Tax?

Google Inc. has a new project, Renewable Energy Cheaper Than Coal. Google is preparing to bet megabucks, mega-engineers and its cutting-edge reputation on its ability to propel solar thermal power, wind turbines and other renewable electricity up the innovation curve and under the cost of coal-fired power, Reuters reported Tuesday.

"Our goal is to produce one gigawatt [1,000 megawatts] of renewable energy capacity that is cheaper than coal. We are optimistic this can be done in years, not decades," said Larry Page, Google’s co-founder and president of products, according to Reuters.

To which we at the Carbon Tax Center say: Good luck, and don’t forget to hire the lobbyists. You’re going to need them to help win a carbon tax, ’cause without the tax, your goal of renewable energy cheaper than coal is likely to remain out of reach.

Don’t look to "market forces" to jack up the cost of coal-fired power. Unlike the 1970s, when the price of coal marched in lockstep with skyrocketing oil, coal prices are stuck in a proverbial peat bog. The national average coal price so far this year, $1.77 per million btu, is barely higher in nominal terms (and 40% less in real terms) than the 1982-1985 plateau of $1.65. The resource is abundant, mining technology is technically mature (if socially and ecologically devastating), and there’s barely a mine workers union to speak of. The power plants themselves are no harder to build, even with SOx and NOx scrubbers, than my kids’ Harry Potter lego’s, they just take a few years longer.

Coal-fired power isn’t about to get much more expensive by itself. Are renewables going to get much cheaper? Arguably not — at least not enough to win Google’s bet.

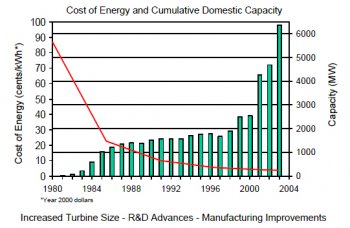

What about electricity from wind, my personal favorite energy-supply source and one for which I’ve done my share of advocacy? Wind power has gotten fabulously cheaper over the past two dozen years, as this DOE cost curve attests. But the rate of decline has slowed. Past advances — taller towers to capture higher wind speeds, larger blades to sweep larger areas, gearing to grab every available erg — appear pretty much tapped out. Further declines in wind costs will be incremental, not quantum. And to compete toe-to-toe with coal as baseload power, wind will need a support system of storage and transmission that will only add to its per-kWh cost.

What about electricity from wind, my personal favorite energy-supply source and one for which I’ve done my share of advocacy? Wind power has gotten fabulously cheaper over the past two dozen years, as this DOE cost curve attests. But the rate of decline has slowed. Past advances — taller towers to capture higher wind speeds, larger blades to sweep larger areas, gearing to grab every available erg — appear pretty much tapped out. Further declines in wind costs will be incremental, not quantum. And to compete toe-to-toe with coal as baseload power, wind will need a support system of storage and transmission that will only add to its per-kWh cost.

Photovoltaics have more cost-cutting ahead but are starting from a much higher cost plane. I’m less up to speed on solar-thermal, but I suspect it sits somewhere between wind and PV — cheaper than PV now but with less scope for innovation. The bottom line, then, as I see it, is that coal will continue to undercut renewables in cost for the foreseeable future.

Unless a price is put on coal’s head.

An average kilowatt-hour from a coal-fired power plant sends 2 pounds of CO2 into the atmosphere. A megawatt-hour (1,000 kWh) puts up a ton. Charge $10 a ton of CO2 (or $37 a ton of carbon — precisely what we at the Carbon Tax Center recommend as the yearly increase in a phased-in tax) and you lift the price per coal-fired kilowatt-hour by one cent. If the gap between wind power (sans the federal Production Tax Credit) and coal power is conservatively put at 4 cents/kWh, then $40/ton of CO2 ought to give Google its Holy Grail.

There’s already a couple of carbon tax bills rattling around the House Ways & Means Committee. The Larson bill (that’s John B. Larson of Connecticut, a member of the Democratic leadership) calls for $15/ton of CO2 in starting in 2008, with the level increasing by 10% annually along with an additional inflation-offsetting adjustment. That could bring wind halfway to parity with coal in just a few years.

Hiring genius engineers and pouring Google’s coffers into renewables are terrific moves. But nothing beats getting the prices right. Earth to Google: start pulling for a carbon tax.

A Carbon Tax When Oil Approaches $100/Barrel?

Rising Global Demand for Oil Provoking New Energy Crisis according to today’s New York Times. Yesterday’s front page of the Wall Street Journal headlined As Energy Prices Soar, U.S. Industries Collide.

Why not just rely upon high gasoline prices to bring down demand instead of “adding insult to injury” with a carbon tax?

One reason is that high gasoline prices alone are not enough to reduce consumption of gasoline and the resulting carbon dioxide emissions. Consumers, whether businesses or households, need a clear price signal that future prices are going to remain high before they are motivated to make the investment decisions necessary to reduce consumption. The volatile gas prices of the last few years just don’t provide that kind of signal. The rising global demand for oil headlined in the Times story is faster in developing countries, but as the Times correctly noted, “Americans’ appetite for big cars and large houses has pushed up oil demand steadily in this country, too.” The problem is that while it may be a rational economic decision to invest in a more efficient car, house, truck or airplane if gas prices are expected to remain at or above current levels, the economic decision-making is very different if consumers believe prices may plummet in two months. Europe has had considerably higher gasoline prices for many years and, not coincidentally, Europeans generally drive much smaller and more efficient vehicles.

While volatile prices do not encourage investment in efficiency, a clear and certain trajectory of increasing carbon taxes would do so. The revenue-neutral carbon tax proposed by the Carbon Tax Center provides that clear price signal. And, the gradual trajectory of increased prices that we propose gives consumers time to adjust to the higher prices by both investing in efficiency and making behavioral changes that will further reduce energy use. For more on how consumer demand for gasoline responds to price, see our issue paper by clicking here.

Another important reason why a carbon tax continues to be essential even with high oil prices is that the goal of a carbon tax is to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, not just to reduce consumption of gasoline. Generation of electricity accounts for approximately 40% of carbon dioxide emissions , compared to about 21% from gasoline and 4% from aviation. Two-thirds of the emissions reductions from a carbon tax are expected to come from the electricity sector, 11% from gasoline and only 1% from aviation. Coal use is increasing and will continue to increase without a price signal that reflects the harm caused by carbon dioxide emissions from coal-fired electric generating plants.

In addition, high oil prices encourage the development of new sources of energy with huge carbon dioxide emissions such as the Alberta oil sands projects. Tar sands development is the single largest contributor to the increase in climate change in Canada according to Greenpeace Canada. Even worse, according to a study by the Sage Centre and World Wildlife Fund-Canada, "voracious water consumption by Alberta’s oilsands threatens the quality and quantity of water available to Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories through the Mackenzie River system." In fact, today’s New York Times cites a new study finding that "[h]igh levels of carcinogens have been found in fish, water and sediment downstream from Alberta’s huge oil sands projects." A carbon tax would reduce the economic incentive for such projects by holding down the price of oil. A carbon tax actually applied to such projects would destroy their economics.

Finally, right now the high oil prices are enriching oil producing countries and oil companies and causing severe damage to the United States economy. A revenue-neutral carbon tax will reduce demand and lead to reduced prices for the oil itself. The results? Reduced carbon dioxide emissions, less money going overseas and to big oil companies, carbon tax revenues returned to all Americans and strengthening our economy, and increased national security as we reduce our dependence on foreign oil. Win-win-win-win!

[To see a summary of recent Carbon Tax Center activities, see A Convenient Tax – Issue #3 immediately below.]

Who is Daniel Sperling and why is he saying bad things about carbon taxes?

Yesterday’s Los Angeles Times ran an odd op-ed calling carbon taxes an ineffectual antidote to global warming. Unlike other critiques that brand carbon taxes as politically unpalatable, this one argued that they’re simply not up to the job of cutting carbon emissions:

“Carbon taxes — taxes on energy sources that emit carbon dioxide (CO2) — aren’t a bad idea. But they only work in some situations. Specifically, they do not work in the transportation sector, the source of a whopping 40% of California’s greenhouse gas emissions (and a third of U.S. emissions).”

I’ve known Daniel Sperling, the author of the op-ed, for decades. As the long-time director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at UC-Davis, Dan probably knows as much about automotive engineering as anyone in the world. What’s more, he’s conscientious, tireless and concerned.

So why do I think he’s wrong about carbon taxes? Actually, Dan is part right, but his message is wrong. Let me explain.

So why do I think he’s wrong about carbon taxes? Actually, Dan is part right, but his message is wrong. Let me explain.

It’s been clear for awhile that carbon taxes won’t make a huge dent in carbon emissions from gasoline — relative to their impact on the biggest source of U.S. carbon dioxide: coal-fired electricity generation. There are three reasons:

- Gasoline has less carbon per btu than coal.

- Engines make better use of their btu’s than do power plants.

- Americans are less behaviorally sensitive to higher prices for gas than for electricity.

When we ran the numbers here at the Carbon Tax Center, we found out just how much gasoline would underperform while electricity overachieved under a level carbon tax. Using Colorado as a test case, we estimate that a statewide carbon tax would draw 60% of all of its carbon reductions from the electricity sector (which is responsible for 42-43% of that state’s CO2), but only 10% from gasoline (which accounts for 20% of emissions).

So we agree with Dan on some key facts. But we think he’s let his natural pessimism about price incentives (he’s an engineer, after all) run a bit amok.

For one thing, the low (10% or less) price-sensitivity for gasoline Dan cites (from his own UC-Davis study) is short-run only. The long-run price-elasticity of gasoline demand is invariably much higher since it can reflect long-term investment decisions — by households in buying more efficient vehicles, by automakers in designing and producing them, and by everyone in making location decisions that reduce driving.

Two widely respected transportation economists at UC Irvine, Ken Small and Kurt Van Dender, looked at pretty much the same gasoline data as Dan and observed the same low (under 10%) short-run price-elasticity. Unsurprisingly but importantly, Small and Van Dender found gasoline’s long-run price-elasticity to be much higher, approximately 40%.

Using that figure, and making assumptions similar to Sperling’s about the potential for substituting lower-carbon fuels, we find that a ramped-up carbon tax that increased the price of gas 10 cents a gallon every year for a decade would reduce CO2 emissions from motor vehicles further and faster than the Low-Carbon Fuels Standard Sperling touts in his op-ed.

Again using Colorado as a test case, the same carbon tax would eliminate more than five times as much CO2 in the electricity sector and almost three times as much in “other” sectors (trucking, space heating, aviation, etc.). Indeed, that tax, which in carbon terms tacks on a charge of $37 per ton (or $10 per ton of CO2) each year for 10 years, would lop off almost 40% from that state’s carbon emissions by 2020. And the revenue stream would be enormous — enough to permit the legislature to zero out the widely disliked state Sales Tax and Business Personal Property Tax by the fifth year, even while providing generous per-resident and per-employee rebates, supplementing the federal Earned Income Tax Credit to assist low-income families, and financing targeted investment in energy efficiency and renewable energy.

We’ll grant the point made by Dan (or the Times’ editors) at the top of his piece: Taxes on CO2 emissions alone won’t get us where we need to go. We’ll need judicious and creative incentives and regulations in addition to a carbon tax, and the Low-Carbon Fuel Standard that Dan is helping advance in California fits that bill. But let’s stop the nay-saying over carbon taxes. They’re the powerful tailwind America needs to get our carbon emissions down equitably, efficiently and immediately.

Photo: Tony.Gonzalez’s photostream (Flickr)

When Snow Won’t Fall

We’re forever on the lookout at the Carbon Tax Center for new and outsized ways in which Americans are using energy. Too often, today’s novelty item is just a clever marketing campaign away from tomorrow’s sizeable carbon emitter. Witness high-definition televisions, or Jet Skis.

If history is a guide, efficiency standards to govern new devices’ fuel consumption won’t be promulgated until after they have proliferated — if ever. Carbon taxes, in contrast, could help rein in new products’ energy requirements from the git-go, i.e., in the design stage. Where a product has little redeeming social value, the price signals from a carbon tax might even keep it from gaining a toehold in the culture.

These thoughts came to mind when we read an article in The New York Times last week about suburbia’s latest must-have energy-guzzlers: home snowmaking machines.

These thoughts came to mind when we read an article in The New York Times last week about suburbia’s latest must-have energy-guzzlers: home snowmaking machines.

“Since Nature can no longer keep to her early deadlines,” The Times reminded us in a veiled nod to climate change, dads from Darien to Denver “are taking matters into their own hands, and creating their own seasons, at least when it comes to winter.”

They’re doing it with snowmakers — machines named “Backyard Blizzard” and “Snow at Home” that feed on water and run on electricity, lots of it. According to the manufacturer, the Blizzard Sport model uses 2 kilowatts. The Times article gave a lower figure — which didn’t appear until the nineteenth paragraph and came with the curious note that “a clothes dryer guzzles more power.”

Of course, most clothes dryers aren’t left on for two days straight. That’s how long a snow-loving Greenwich, CT developer profiled in The Times story had been running his two snowmakers when the reporter dropped by.

Another two-machine man, owner of a boat repair business owner near Atlantic City, NJ, made this admission: “My neighbors are going to work at the casinos at 3 a.m. and I’m out there, too, messing with the guns. It’s really hard to turn the guns off.”

Hmm, what did Miles Davis tell Coltrane when the saxophonist said he sometimes didn’t know how to end a solo? “John, just take the horn out of your mouth.” In this case, given the large helpings of fossil fuels that go into powering snowmakers, a carbon tax might provide a strong incentive to users to turn them off, or to refrain from buying them in the first place.

We calculate that using two snowmakers — one evidently isn’t enough — twice a month, for two days straight, over four months of the year consumes around 3,000 kWh — enough to pump out 1,220 pounds of CO2, based on the national average mix of fuels used in making electricity. On that average, the $370/ton carbon tax that CTC proposes (after a 10-year phase-in) would add

$225 a year in operating costs.

Based on the high price-elasticities for many luxury goods, the tax might be expected to reduce sales of home snowmakers by around a third. That’s a nice hit, though admittedly it’s far from the 75% market shrinkage that is probably needed to strangle the snowmaker industry in its cradle. (Achieving that through a tax disincentive alone would require a carbon tax five times larger than the one CTC is seeking.)

Which suggests that by itself a carbon tax won’t determine the outcome every time. But it would nudge some of us away from making certain climate-damaging choices. And at least the polluter — whether it’s a giant factory or, as in this case, dear old snowmaker dad — would be made to pay.

Photo: el moose / Flickr