The weed-growing, road-biking, jeans-wearing candidate for president won’t be endorsing a carbon tax after all.

Libertarian Party nominee (and former New Mexico governor) Gary Johnson had signaled his openness to a revenue-neutral carbon tax in an interview last week with the New York Times’ John Harwood. As Harwood reported:

He [Johnson] also distinguishes himself from most contemporary Republicans by accepting the reality of what he calls “man-caused” climate change. As a solution, he wants to explore taxing carbon — not for the revenue, but to provide a financial incentive to reduce emissions. “That may have the result of being self-regulating,” Mr. Johnson said. “The market will take care of it.”

Libertarian presidential candidate Gary Johnson at a rally at the University of Nevada in Reno this month. Photo credit: NY Times.

Credit Harwood for hinting (“not for the revenue”) that Johnson was trying to align himself with a revenue-neutral carbon tax. Unfortunately, Johnson failed to spell out how the revenues from his carbon tax would be returned to U.S. households. While his use of the word “fee” (see below) suggests he had in mind the fee-and-dividend scheme advocated by the Citizens Climate Lobby (and backed by us at CTC), he never actually said so, leaving him open to charges from aggrieved libertarians that a Johnson administration was looking to increase their tax burden.

It didn’t take long for Johnson to walk back his carbon-tax talk, in this interview with Nick Gillespie, editor-in-chief of the libertarian Web site reason.com, last Friday:

NICK GILLESPIE: Earlier this week, you suggested you were in favor of a carbon tax or fee. Yesterday, at a rally in New Hampshire, you said you were against it. What is your position on carbon taxes?

GARY JOHNSON: [A carbon tax] sounds good in theory, but it wouldn’t work in practice. I never called it a tax. I called it a fee. As it was presented to me, this was the way to reduce carbon and actually reduce costs to reduce carbon. Under that premise—lower costs, better outcomes—you can always count on me to support that [sort of] notion. In theory it sounds good, but the reality is that it’s really complex and it won’t really accomplish that. So, no support for a carbon fee. I never raised one penny of tax as governor of New Mexico, not one cent in any area. Taxes to me are like a death plague.

GILLESPIE: You do believe that climate change is happening and that human activity adds to it. Does that mean it is an issue that should be addressed by government policy?

JOHNSON: Well, I’ll agree with the first two, but I’m a skeptic that government policy can address this. The United States contributes 16 percent of the contribution of carbon in the world…

GILLESPIE: So you would be against the United States unilaterally making any kind of move that puts a huge economic disadvantage that also wouldn’t really mitigate carbon?

JOHNSON: If there is any way we can address this issue without the loss of U.S. jobs, my ears are open.

Whew. Does Johnson have a reasoning deficit, or was he just trying to avoid having to explain himself to other libertarians? Who knows, but either way Johnson’s turnabout deprives U.S. voters of a chance to learn about the least complex way to tackle climate change: to charge an “upstream” fee on fossil fuels’ carbon content and “dividend” the proceeds equally to every American household, thus adhering to the spirit of “no new taxes,” while the resulting higher prices of fossil fuels spark a steady but relentless transformation of the U.S. energy system from dirty to clean energy.

What’s further disappointing in the exchange with Gillespie is Johnson’s apparent ignorance of the potential of a U.S. carbon tax — particularly the simple and transparent fee-and-dividend version — to spark parallel measures in other countries. That would have put the lie to two big canards about a U.S. carbon price: that it can only affect a fraction of global emissions, and that it would hobble U.S. industries, costing American jobs.

Johnson did leave himself a possible out by saying he might reconsider “if we can address this issue without the loss of U.S. jobs.” Still, his backtracking makes it harder for that oft-rumored but still unseen cadre of climate-concerned Congressional Republicans to come out for a carbon tax after the November elections.

Worse for himself, though, Johnson blew an opportunity to win over voters who want climate action but have been disinclined to vote for Clinton.

Then again, Johnson’s muddled talk about vaccination — further on in the Gillepsie interview he said he wants it left to individuals’ choice — might have repelled those voters anyway. At the least, it suggests a pervasive ignorance about externalities and “the commons,” about economics and ethics.

Whether Johnson and other libertarians like it or not, our vaccination decisions affect each other. So do unpriced carbon emissions.

Addendum: For you libertarians out there, Forbes contributor Tim Worstall’s post critiquing Johnson’s flip-flop is worth reading.

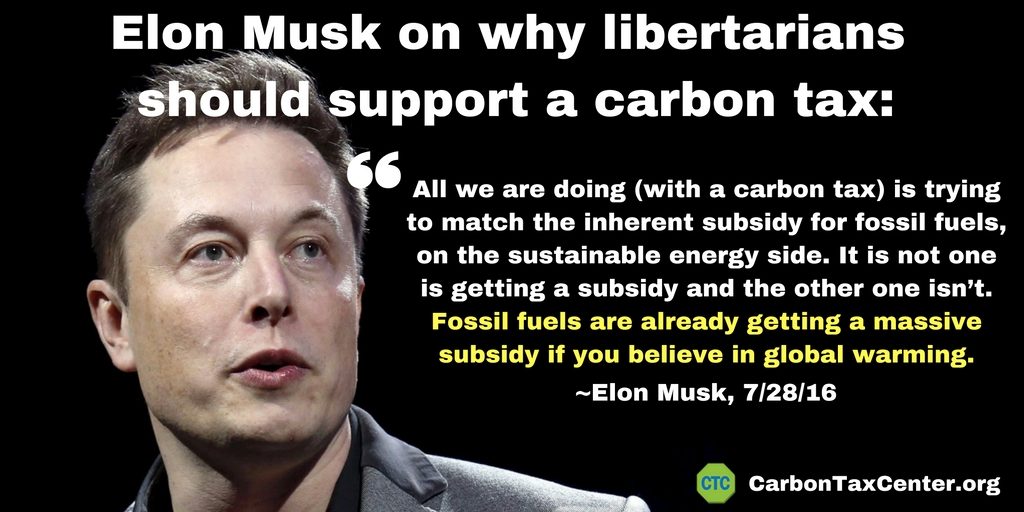

In Nevada, Musk also spoke up for carbon taxes, though hardly for the first time. Four years ago, for example, at the Wall Street Journal’s ECO:nomics conference in Santa Barbara, CA, Musk disparaged tax credits for green cars and declared that “the best method for addressing climate change in the automotive industry is to impose a tax on carbon dioxide emissions,” according to the trade journal

In Nevada, Musk also spoke up for carbon taxes, though hardly for the first time. Four years ago, for example, at the Wall Street Journal’s ECO:nomics conference in Santa Barbara, CA, Musk disparaged tax credits for green cars and declared that “the best method for addressing climate change in the automotive industry is to impose a tax on carbon dioxide emissions,” according to the trade journal