This post is adaped from my essay yesterday on Streetsblog USA, A Lesson for NYC’s Congestion Pricing Came Last Week from Washington State. It was posted on the eve of NY Gov. Kathy Hochul’s announcement today that she has ended her June “pause” and authorized New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority to begin implementing a scaled-down but still-robust version of the original plan, beginning at midnight January 5, 2025.

The Streetsblog post was intended to steel Hochul’s courage and, as we congestion pricing advocates have demanded since June, to prod her to “flip the switch” on the Manhattan toll scheme that was set to go into effect on June 30. It was actually written last weekend with the hope of placing it in the New York Times, but they could not fulfill our request for rapid publication. No matter, the governor’s turnaround was already in the works.

The post takes a few liberties with actual events in Washington, eliding the differences between the straight-up carbon tax measure that voters rejected in 2016 and the cap-and-trade measure that also failed at the ballot in 2018, and the state’s Climate Commitment Act that was enacted into law in 2021 and backed by voters last week. This was in service of the larger point: that the conception of what is fair changes when an effective policy has been given time to work, and that if a policy is wise, politicians should stay the course, confident that public support will emerge.

We’ll have more to say in the coming weeks about the pending rollout of New York’s congestion pricing plan, arguably the first-ever large-scale application of externality pricing in the U.S.

— C.K., Nov. 14.

The first time Donald Trump was elected president, in 2016, Washington State residents also voted down an initiative that would have created the country’s first statewide carbon tax.

The second time Trump won the presidency, last week, Washington residents flipped their 2016 stance on carbon pricing, voting to preserve the comprehensive carbon pricing program that their legislature ended up enacting. And therein lies a message for New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, who paused New York City’s Central Business District toll plan on June 5, just as it was about to go into effect after years of debate.

The message: If the policy is wise, stay the course. The facts on the ground will soon change, generating the political support to validate your policy and prepare you for the next policy battle.

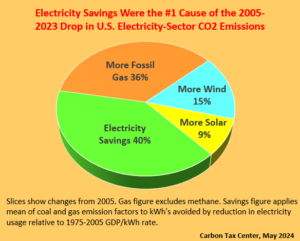

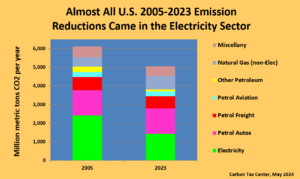

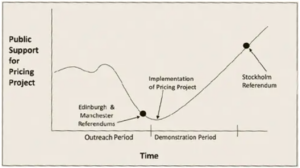

The famous chart of why politicians should stay the course when a policy is good, but unpopular.

Congestion pricing proponents have always known the odds. Taxes are unpopular, check. Driving is a birthright and change is hard, check. We were aware congestion pricing in London and Stockholm had only 40 percent favorability before adoption. But both cities’ experience showed that once traffic visibly lessened and transit improvements got underway, opinion flipped. Roughly 60 percent of residents now support the tolls.

The 2016 vote against Washington carbon pricing was a landslide: 59.3 percent no to 40.7 percent yes. The 2024 vote to keep the state’s carbon pricing law was a landslide in the opposite direction: 62 percent to keep it and 38 to repeal it. Hmm, looks like that 60-40 rule has legs!

A brief look at the law that Washington State voted to keep last week will demonstrate how it’s cut from the same cloth as New York’s congestion pricing.

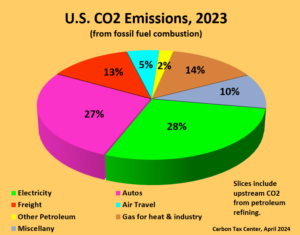

Washington’s innovative Climate Commitment Act requires fossil fuel companies to buy permits keyed to the carbon content of their fuels. That includes oil refineries, which pass on the costs of the permits to motorists and homeowners as higher prices for gasoline and heating fuels.

The intent is to motivate industry and consumers to curb their carbon dependence, much like congestion pricing in New York would impel motorists to drive less often into gridlocked Manhattan. Sales of the emission permits in Washington are already helping finance electrification and renewable-energy substitutes for fossil fuels, just as New York’s congestion revenues would have bankrolled $15 billion in better transit.

And just as it has been in New York, the road to this decision wasn’t easy. Washington’s climate law took root after voters twice rejected ballot referendums for statewide pricing of carbon emissions by margins of around 60 to 40. (A 2018 initiative failed as well, 56.6 percent to 43.3percent.) But after Democrats won control of the legislature in 2020, Gov. Jay Inslee, a Democrat and unabashed climate champion, pushed through the Climate Commitment Act, much as New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo in 2019 won legislation directing the regional transit authority to institute a congestion pricing system.

This year, however, fossil fuel backers in Washington collected enough signatures to place Initiative 2117on the Nov. 5 ballot. A “yes” vote would have repealed the legislation and discarded the emission permits — perhaps slowing energy price increases but stalling the state’s shift toward clean power.

Well, the returns are in, and supporters of the emissions permit scheme won big.

True, what was on the ballot in Washington last week — making gasoline and other fossil fuels more costly to elevate lower-emission substitutes from smaller cars to electric cars and, best of all, less driving — isn’t the same as congestion pricing. But it’s a close cousin. What stands out is that a policy rejected by nearly 60 percent of voters in 2016 and again in 2018, won with around 60 percent in 2024. Attitudes can shift when facts warrant.

True, what was on the ballot in Washington last week — making gasoline and other fossil fuels more costly to elevate lower-emission substitutes from smaller cars to electric cars and, best of all, less driving — isn’t the same as congestion pricing. But it’s a close cousin. What stands out is that a policy rejected by nearly 60 percent of voters in 2016 and again in 2018, won with around 60 percent in 2024. Attitudes can shift when facts warrant.

What enabled the turnaround? A resolute governor stayed the course, allowing the “default” to recalibrate from cheap gas to clean power and letting the public warm to this novel policy for cutting carbon pollution. Once it did, 20 percent of voters came aboard, just like they did in London and Stockholm.

New York hasn’t been as fortunate yet. This spring, our executive gazed at the pending $15 peak congestion toll and rather than seeing less gridlock and a transformed transit system, saw a political abyss. Advocates and even her own staff tried to brace her for this “valley of political death” between congestion pricing’s initiation and its eventual acceptance. The warnings did no good. On June 5, she placed the tolls on “indefinite pause.”

There is talk that the governor will soon un-pause the tolls now that the suburban House races she feared would be swept up in a congestion pricing backlash are decided. But Gov. Hochul must move with urgency. The incoming president has made his distaste for the tolls abundantly clear. His return to power is less than 10 weeks away, with at least four of those weeks likely gobbled up by red tape. The plan’s logic that Hochul herself once articulated so well remains intact: better commutes and healthier, safer streets.

Hochul must act fast and trust the message from Washington State: with strong leadership, good policy and good politics can be one and the same.

The paper,

The paper,

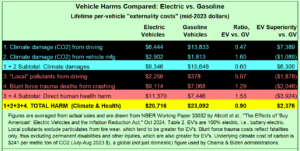

That EVs improve only modestly on GVs under reasonably broad social accounting is sobering. Yes, their climate benefit is substantial, around 1.7 to 1 (throwing in manufacturing CO2 with driving CO2). But that ratio is miles away from a clean sweep. And with NIMBYs, NEPA and other obstacles to a truly green grid, it’s not going to rise very much for a while.

That EVs improve only modestly on GVs under reasonably broad social accounting is sobering. Yes, their climate benefit is substantial, around 1.7 to 1 (throwing in manufacturing CO2 with driving CO2). But that ratio is miles away from a clean sweep. And with NIMBYs, NEPA and other obstacles to a truly green grid, it’s not going to rise very much for a while.

This impressive scale-economy made sense — on paper. Costs tend to track equipment surface areas, while capacity is proportional to reactor volume, portending only a 60 percent rise in costs per doubling of capacity. (Mathematically, two raised to the two-thirds power is roughly 1.6. Why two-thirds? Because surface area rises with the square of length while volume rises with the cube.) This would dictate a 20 percent reduction in per-kW costs from doubling plant capacity. Other cost elements like siting, permitting, engineering, and project mangement would, it was thought, display steeper economies, lifting the overall per-kW cost reduction per doubling of capacity to around 25 percent.

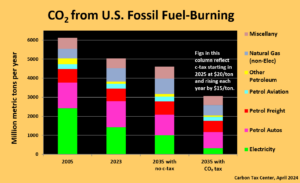

This impressive scale-economy made sense — on paper. Costs tend to track equipment surface areas, while capacity is proportional to reactor volume, portending only a 60 percent rise in costs per doubling of capacity. (Mathematically, two raised to the two-thirds power is roughly 1.6. Why two-thirds? Because surface area rises with the square of length while volume rises with the cube.) This would dictate a 20 percent reduction in per-kW costs from doubling plant capacity. Other cost elements like siting, permitting, engineering, and project mangement would, it was thought, display steeper economies, lifting the overall per-kW cost reduction per doubling of capacity to around 25 percent. For Vineyard Wind, then, and perhaps for the Dogger Bank project as well, paper savings from going large have become a cruel joke, at least for the time being. Putting that aside, I’ve calculated the theoretical carbon price that would raise the sale price of wind electricity by the same amount that a halving of turbine capacity raised its all-in cost. Rephrased as a question: How big of a carbon price would have to be baked into the cost of prevailing fossil-fuel electricity — assumed to be from the mainstay of the U.S. power system, a combined-cycle power plant burning methane gas — to compensate for sticking with prior 6-7 MW sized offshore wind turbines and, thus, foregoing the assumed 25 percent per-kWh cost reduction from doubling turbine sizes to 13 megawatts?

For Vineyard Wind, then, and perhaps for the Dogger Bank project as well, paper savings from going large have become a cruel joke, at least for the time being. Putting that aside, I’ve calculated the theoretical carbon price that would raise the sale price of wind electricity by the same amount that a halving of turbine capacity raised its all-in cost. Rephrased as a question: How big of a carbon price would have to be baked into the cost of prevailing fossil-fuel electricity — assumed to be from the mainstay of the U.S. power system, a combined-cycle power plant burning methane gas — to compensate for sticking with prior 6-7 MW sized offshore wind turbines and, thus, foregoing the assumed 25 percent per-kWh cost reduction from doubling turbine sizes to 13 megawatts?