Christina A. Roberto, health policy expert at the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school and lead author of a JAMA study of Philadelphia’s soda tax, quoted in Tuesday Could Be the Beginning of the End of Philadelphia’s Soda Tax, New York Times, May 21.

California Stars: Green Power from Enlightened Governance

Editor’s note: On May 31, energy-climate blogger David Roberts posted How California became far more energy-efficient than the rest of the country, a gorgeous distillation of our report, “California Stars.” Roberts’ post explains the policy dynamics underlying our report’s quantitative findings and shows how California has made energy efficiency and renewables the focal point of the state’s economy. His post also makes clear how far all 50 states still have to go while placing “California Stars” in the national political context.

Yesterday the Natural Resources Defense Council released California Stars, my report quantifying and documenting California’s relative success in decarbonizing its economy since the 1970s. I say “relative” because the report’s measure of success involves not one but two relational metrics: carbon reductions relative to economic activity, and California relative to the other 49 states.

I was lead author of this NRDC report documenting how California has surpassed the rest of the U.S. in decoupling economic growth from fossil fuels.

California Stars: Lighting the Way to a Clean Energy Future establishes that from 1975 to 2016, the nation’s largest state reduced the fossil fuel inputs needed to support a constant amount of economic activity 18 percent faster than the rest of the country — a difference with enormous climate consequences. Had the other 49 states matched California’s rate of improvement, the report finds, annual emissions of carbon dioxide nationwide would be lower today by nearly 25 percent, or 1,200 million metric tons of CO2 — the equivalent of all carbon pollution from U.S. passenger vehicles.

There’s more about California Stars further below and in a graceful blog post by long-time NRDC attorney and energy strategist Ralph Cavanagh, who oversaw the report. I was principal author, which may come as a surprise to readers who have followed my career of late. For one thing, the report has nothing to do with carbon taxing. Moreover, a decade ago NRDC and I were on opposite sides of an internecine struggle over carbon pricing, with NRDC backing cap-and-trade and me, on behalf of the Carbon Tax Center, insisting on straight-up carbon taxes. More recently, in 2015, in a blog post, What an Energy-Efficiency Hero Gets Wrong about Carbon Taxes, I went to considerable lengths to counter criticisms from an NRDC energy-efficiency superstar that carbon taxing was too blunt an instrument to do much good in cutting down emissions.

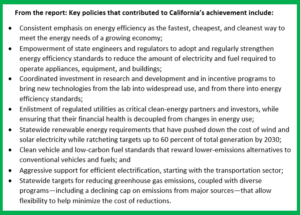

All the same, for over 40 years it has been abundantly clear, even from my East Coast perch, that even without a carbon tax, California’s government has steered its economy more assertively toward energy efficiency and renewable energy than has any other U.S. state. (California does have a modest cap-and-trade program.)

Through the California Energy Commission, a first-of-a-kind agency legislated in the last year of Gov. Ronald Reagan’s administration and staffed in Gov. Jerry Brown’s first (1974 and 1975, respectively), California established not just the first efficiency standards for major appliances and buildings but a process for continually updating those standards to align with — and further incubate — technological advances by which cooling, heat and light may be furnished with progressively smaller energy inputs. These policies, along with innovations that enabled electric and gas utilities to bankroll customer “end-use” efficiency investments, later spread to most of the other 49 states, greatly amplifying their single-state impacts. But they took root first and, it appears, most deeply in California.

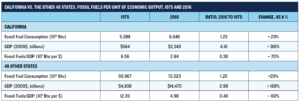

Table 1 from “California Stars” shows that from 1975 to 2016 California reduced its use of fossil fuels per unit of economic output by 70%. For the other 49 states collectively, the reduction was only 60%. That percentage difference equates to 1,200 million excess metric tons of carbon pollution in 2016 alone—a huge missed opportunity for the rest of America.

Needless to say, these policies thrilled me, even from afar. And the policies themselves seemed firmly planted in a statewide culture of energy efficiency and innovation. To be sure, you couldn’t discern that culture in the state’s sprawling subdivisions and freeways, but you could sense it in the passionate conversations about energy that caromed among the policy beehives that were springing up around the state: at the California Energy Commission and the state Department of Natural Resources; at the University of California’s Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory and its Energy Resources Group and at Stanford; at NRDC, which was making efficiency standards sexy not only to other environmentalists but to appliance manufacturers and builders; and at the Environmental Defense Fund, whose pathbreaking analyses were suggesting that investing in efficiency and renewables could make utilities financially stronger.

The font of this activity was Gov. Brown. Whether or not he grasped all of the intricacies — and he probably did — Brown’s personal asceticism and hippie-ish disdain for standard modes of consumption (at least in his first go-round as governor) seemed to furnish the cultural DNA for California’s quiet but consequential energy-policy revolution. This was palpable during my three working trips to the state during Brown’s first term: in 1976 when I campaigned around the state for a ballot measure limiting new reactors; in 1977 when I testified for EDF and NRDC in nuclear power siting cases in San Diego and San Francisco; and in 1978 when I spent a month in Los Angeles with the PhD economist Vince Taylor, workshopping my analyses of cost escalation in nuclear power.

Within a year, that work would catapult me to national prominence, when the Three Mile Island reactor outside Harrisburg, PA melted down and I, providentially, had the computer printouts (regression analyses of the relentlessly rising costs to build nuclear plants throughout the 1970s) that answered the question on the lips of seemingly every energy-journalist in America: what would the TMI accident do to nuclear power economics? Almost overnight, my energy-policy work narrowed to a single-minded focus on nuclear power costs — which ended only when I took up urban-bicycling advocacy near the end of the 1980s.

Within a year, that work would catapult me to national prominence, when the Three Mile Island reactor outside Harrisburg, PA melted down and I, providentially, had the computer printouts (regression analyses of the relentlessly rising costs to build nuclear plants throughout the 1970s) that answered the question on the lips of seemingly every energy-journalist in America: what would the TMI accident do to nuclear power economics? Almost overnight, my energy-policy work narrowed to a single-minded focus on nuclear power costs — which ended only when I took up urban-bicycling advocacy near the end of the 1980s.

By the early eighties, then, I had to give up my close watch on California’s energy efficiency progress. Last September, however, with Gov. Brown’s fourth and final term drawing to a close and with climate concern skyrocketing in the U.S., the time seemed right to determine how far California had actually gotten off fossil fuels since the start of that quiet revolution in energy governance in the seventies. CTC intern (and U-Chicago rising sophomore) Rohan Kremer Guha and I dug up California-specific fossil fuel and GDP data and placed it alongside data for the U.S. as a whole, which led to a preliminary version of the table above.

In a nutshell, we found that from 1975 (the approximate start date of that revolution) to 2016 (the most recent year with consistent data):

- California’s use of fossil fuels increased by 23 percent, a bit more than the rate for the rest of the U.S. (20 percent)

- During that same period, California’s economy more than quadrupled in size, far surpassing the other 49 states’ tripling

- Adjusting the first figures by the second, California reduced its use of fossil fuels per unit of GDP by 70 percent; for the rest of the U.S., the reduction rate was 60 percent

The last bullet point led directly to the startling finding reported at the top of this post: Had the other 49 states reduced fossil fuel use relative to economic activity at the same pace as California, nationwide carbon emissions would have been lower in 2016 by 1,200 million metric tons, or 24 percent.

Proof indeed, not just of California’s leadership but of the rest of the country’s sluggishness . . . and of the consequences of the gap between the two. Because of that sluggishness, the U.S. missed a chance to eliminate carbon pollution equivalent to CO2 emissions from all 200 million passenger cars and (light) trucks in the country. I pitched a report built on this analysis to our friends at NRDC, and our collaboration produced this report.

I’ll have more to say soon, not just on the report itself but on what it says about Jerry Brown’s climate record. You can download the report (pdf) directly from NRDC’s Web site and comment on it here via the link just below the headline near the top of this post.

Avoiding climate breakdown will require cathedral thinking. We must lay the foundation while we may not know exactly how to build the ceiling.”

Swedish climate campaigner Greta Thunberg, addressing Parliament (U.K.), quoted in The Uncanny Power of Greta Thunberg’s Climate-Change Rhetoric, The New Yorker magazine, April 24.

A decade ago, I thought the most efficient climate policy is making dirty energy more expensive. It is the most efficient, but if politically it can’t happen, well, then it’s not the most efficient.”

NY Times op-ed columnist David Leonhardt, discussing his Sunday Times Magazine article, The Problem With Putting a Price on the End of the World, April 13. (The quote appears on p. 6 in the magazine’s print edition and is not available digitally.)

An Historic Win in NYC Could Pay Huge Climate Dividends

“We have now disproved the idea that we’re never, in this country, going to tax or charge a significant environmental harm.” That quote, uttered by me this morning to a writer for Earther magazine, is as good a lead-in as any to tell you about an historic victory in New York that I view as a big shot in the arm for carbon taxing.

See opening paragraph for link to the story in Earther magazine.

This past weekend, our state legislature approved a far-reaching, first-time-in-this-hemisphere plan to charge vehicles driven in the heart of a big city — mid and lower Manhattan in this instance — a congestion fee. While the bill punts key details to a new city-state panel, the contours are clear enough: driving a private car into the “congestion zone” south of 60th Street will cost as much as $12 during peak hours, with higher fees for trucks. When the plan starts up, in January 2021, traffic in the zone is expected to thin enough to raise travel speeds in the zone by 12-15%; that figure will rise as the estimated billion dollars a year in congestion revenues (paid by the remaining vehicles) are invested in modernizing the subways.

As most Carbon Tax Center followers and supporters know, I worked hard for this win. Over the past dozen years I spent 5,000 hours (!) creating and deploying a spreadsheet model that is kaleidoscopic enough to calculate the traffic and revenue and environmental benefits of any Manhattan pricing scheme, yet transparent and nimble enough to be used by other Excel jockeys — including the consultants that the governor’s office hired to scope out congestion pricing. I also wrote scores of posts for Streetsblog, the scrappy and admirable blog that is a nerve center for NYC’s “livable streets” community, each post aimed at steeling advocates on some aspect of congestion pricing math, policy and politics.

I say this not to tout my role. The forces that coalesced behind congestion pricing and made it unstoppable were immense, as they had to be to bring along the governor and legislature in the face of widespread cynicism, apathy, resentment and motor-worship. There were scores, then hundreds, then thousands of advocates pushing for this. That said, I believe that my years of calculations, both mathematical and political, lent gravitas to my thoughts on the meaning of this victory.

The huge mutual regard among NYC “livable streets” advocates helped push congestion pricing through the legislature.

New York’s enactment of congestion pricing is a big win for climate. Not in the sense of immediately reducing carbon emissions. By itself, the charging scheme will eliminate only around a million tons of CO2 a year (half by reducing vehicle use, and half by diminishing stop-and-go traffic). That’s a mere 1/5,000 of U.S. emissions. But it will make New York — and other U.S. cities, if they follow suit — more fair, civilized and prosperous. That will help shrink the country’s carbon footprint by fostering growth in “inherently green” (smaller-footprint) cities rather than sprawled-out suburbs and exurbs, as Jeff Blum and I pointed out last month in The Nation (and on this blog).

But an even bigger payoff lies, I believe, in establishing the precedent of finally taxing an environmental harm. With congestion pricing, the harm being taxed isn’t emissions, it’s traffic congestion (more technically, each vehicle’s “congestion causation” from abetting the slowing of traffic). The same principle — the most direct way to effectuate less of something is to price it at its true cost — animates carbon taxing.

Society is concluding at last that carbon emissions must be shrunk, rapidly and radically. That requires (i) intelligently regulating sources of emissions (building codes, efficiency standards), (ii) judiciously subsidizing evolving alternatives (wind, solar), (iii) researching and developing promising new low-carbon demand and supply technologies, and (iv) taxing fossil fuels so that their climate damage figures in their price.

U.S. states and, at times, the national government haven’t done a bad job on the first three. But we’ve never done the last: taxing fossil fuels’ carbon content and emissions. Indeed, we’ve never explicitly taxed any large-scale environmental harm. And the double defeat of carbon tax initiatives in Washington state made it easy to lose hope that we ever would.

Now, the enactment in New York of a plan that frontally taxes a major societal harm — driving in a congested (and transit-rich) city center — has disproved the idea that substantially taxing an environmental harm is impossible in the U.S. We can put that particular bit of defeatism to rest.

To be sure, enacting a national carbon tax remains a far heavier lift than a single city or state passing congestion pricing. While regional factionalism — between Manhattan and the boroughs, between NYC and its suburbs — was a big hurdle, congestion pricing’s lesser scale allowed the transit benefits from the congestion revenues to take center stage in the advocacy campaign.

Indeed, subway relief paid for with congestion tolls emerged as a far more powerful organizing theme than congestion relief itself. So be it. The takeaway is to make a publicly guided, investment-based program — a Green New Deal — the rubric for tackling climate change and enacting a robust carbon tax as both a pay-for and a powerful change agent.

We’ll post more about that in the coming weeks. For now, it’s fair to say that carbon taxing for the U.S. has taken a major step forward. With enactment of congestion pricing for New York City, the road to a carbon tax and meaningful climate policy has definitely gotten clearer.

I’m looking at global warming — I don’t need to see the graphs. I’m living it and everybody else here is living it.”

Cathy Crain, mayor of Hamburg, IA, referring to the role of climate change in increasing the frequency of extreme weather events, following two record-setting floods that devastated Hamburg in a single decade. — An Iowa Town Fought and Failed to Save a Levee. Then Came the Flood., New York Times, March 20.

Green New Congestion Pricing

On Monday, The Nation magazine posted “Congestion Pricing Is New York’s Green New Deal,” a piece I co-authored with fellow transit advocate Jeff Blum, casting congestion pricing in New York City as an initial foray of the Green New Deal. Following is the text of the piece, with an addendum instructing Carbon Tax Center subscribers and allies what they can do between now and March 31 — congestion pricing’s legislative deadline — to push the proposal across the finish line in Albany. — C.K.

While the Green New Deal basks in the national spotlight, a different but parallel policy idea is advancing in New York. That is Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo’s plan for congestion pricing, which will charge motorists to drive in the most car-jammed (and transit-rich) part of the city, Manhattan south of 60th Street.

At first glance the two appear more opposite than related. The Green New Deal is national, congestion pricing is New York-specific. One is expansive, a solar and wind energy-based revitalization of our society and economy. The other seems punitive, making drivers pay for what is now free.

As posted in The Nation. See link at top of this post.

But we believe the two have a great deal in common, both practically and philosophically. Moreover, congestion pricing faces a March 31 legislative deadline to allow initial appropriations for the tolling apparatus to be included in the New York State budget due on that date.

And so we invite Green New Deal adherents — from Massachusetts Sen. Ed Markey and New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to the legions of determined climate justice activists who have put the Green New Deal on the political map — to make congestion pricing in New York a stepping stone to the national fight.

To begin, any program to save the climate depends on having cities thrive. Urban residents use only a fraction as much fossil fuels as suburbanites or rural dwellers, not because they are virtuous but because cities, due to their compactness, are inherently lower-carbon. City residents drive less not just because they can take transit but because destinations are close by. Density also dictates that homes and offices use less power and heat. For cities to thrive and grow, automobile traffic must be tamed and restrained, which congestion pricing does with marvelous efficiency.

Congestion pricing shares DNA with the New Deal through emphasis on public investment. Federal spending in the 1930s strung electric wire and conserved the soil, and federally driven investment going forward can decarbonize our economy. In the same way, the congestion toll revenues in New York can pay to modernize the city’s buses and subways — as happened after London adopted congestion pricing in 2003. Thanks to massive transit investment and reappropriation of street space there, nearly 25% more people now enter the center of London daily, mostly on trains, buses and bikes, while car travel speeds have remained stable.

There’s more. Congestion pricing rests upon the Rooseveltian idea to care for the commons — rivers and forests and farmland. Streets and transit are cities’ commons, which America has allowed cars to plunder for a century.

After years of temporizing, transit advocates in New York have finally resolved that the antidote to broken subways and too many automobiles must include charging vehicles to drive in city centers. Both major transit coalitions, the more business-oriented Fix Our Transit and Fix the Subways, led by the impressive grassroots organizing group Riders Alliance, have put congestion pricing at the top of their political agendas. Before long, we predict, Green New Deal supporters will similarly acknowledge that fully unleashing green energy requires a robust carbon tax, not just as a source of funds but to re-set societal defaults, to re-orient incentives and to unlock innovation.

The Markey–Ocasio-Cortez Green New Deal resolution is adamant about labor rights and economic justice. So too is the movement for congestion pricing. New York City’s most venerable anti-poverty advocate, the Community Service Society, examined congestion pricing and found that for each low-wage New Yorker who regularly drives into Manhattan, nearly 40 will benefit from better trains and buses paid for with the congestion-toll revenues. In the same vein, the right-of-center Manhattan Institute concluded last year that extending New York’s decade-long jobs boom depends on massive and effective investment in mass transit to allow immigrant and other workers to access jobs.

These considerations appear to have finally pushed New York’s Mayor Bill de Blasio off the political fence last month to proclaim support for congestion pricing.

These considerations appear to have finally pushed New York’s Mayor Bill de Blasio off the political fence last month to proclaim support for congestion pricing.

The iconic New York progressive centrist Daniel Patrick Moynihan understood this thirty years ago. As a powerful Senate Committee chairman, he found a way to use a portion of federal gas taxes to decouple urban mobility from automobiles, spurring a rise in transit and bicycling and making cities cleaner and more dynamic.

There is this difference, however. Unlike the Green New Deal, which is open-sourced by design, congestion pricing for New York is being finalized by the state’s governor, who seems intent on keeping the toll levels and other key plan details under wraps till the last minute.

Attempts to toll the entrances to Manhattan’s central core have come up short so many times that any leader worth his Machiavelli might rightly presume that iron-fisted control is the only way to get it done. But that approach is out of step with both the current political era and the enormous momentum to pass congestion pricing in the state budget this month and finally cure the dysfunction of the city’s streets and subways that daily afflicts millions.

A fifth of the way into our new century, awareness is spreading of the folly of giving away for free a finite resource, whether it’s the atmosphere’s capacity to remain temperate or Broadway’s five travel lanes through Times Square.

A Green New Deal, like its illustrious antecedent, can start in New York. Today, congestion pricing can revitalize and unsnarl New York’s subways and streets. Tomorrow, a nationwide mobilization can turn our carbon economy green.

Komanoff, an energy and transportation economist, was “re-founder” of the bicycle advocacy group Transportation Alternatives. Blum was founding executive director of USAction and leader of multiple state and national pro-transit campaigns.

Whether you live in NY State or somewhere else, please visit the Fix The Subway campaign to find out how you can donate time, money or both to pass congestion pricing for New York City now. Or, text DELAY to 52886. Remember, the vote for the budget bill that will include initial allocations for congestion pricing is expected between Friday March 29 and Sunday March 31. Thank you.

“Popular understanding of climate change fails to fully appreciate its irreversibility. Every increment of heat, and every knock-on effect of that heat, is something our species will be dealing with, for all intents and purposes, forever. Can’t ‘get to it later.’ “

Climate blogger David Roberts (@drvox), via Twitter, March 11.

U.S. Climate Concern Is Trending Upward

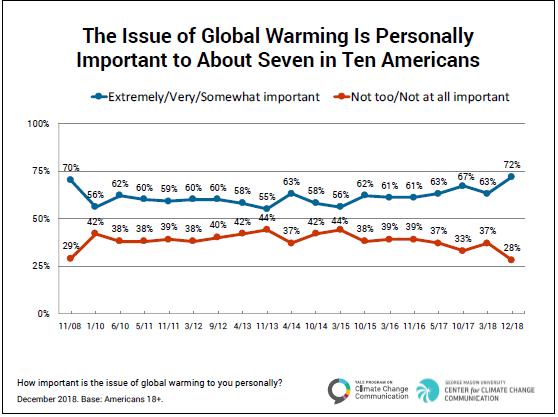

Americans in record numbers now regard climate change not as an abstract possibility but a feature of the here-and-now, according to the latest polling by the highly regarded Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication.

Cover of the Yale-George Mason poll report — the 19th in the decade-long series.

Nearly half of Americans (46%) say they have personally experienced effects of global warming, and roughly the same proportion (48%) believe people in the U.S. are being harmed by global warming “right now,” the Yale-George Mason team reports. Both figures are roughly one-third (15-16 points) higher than in prior surveys and are drawn from interviews with 1,114 adults conducted between Nov 28 and Dec 11 — a period that followed on the heels of the “Camp Fire” that devastated the northern California town of Paradise, but months removed from broiling summer weather in most parts of the country.

More than six in ten Americans (62%) now understand that global warming is largely human-caused, a 10-point increase from March 2015, according to the poll, which may be downloaded in summary (HTML) or full (pdf). Nevertheless, only one in five (20%) recognize the vast agreement among climate scientists around that conclusion, suggesting that the decades-long media-abetted campaign to present “both sides” has obscured this vital scientific consensus.

Here’s how the poll authors reported their key findings:

Our latest national survey finds that a large majority of Americans think global warming is happening, outnumbering those who don’t by more than 5 to 1. Americans are also growing more certain that global warming is happening and more aware that it is caused by human activities. Certainty has increased 14 percentage points since March 2015, with 51% of the public now “extremely” or “very sure” that global warming is happening. Sixty-two percent of the public now understands that global warming is caused mostly by human activities, an increase of 10 points over that same time period.

It’s well-known that political change is driven not just by yes-or-no poll figures but by salience — how strongly voters care, and whether they feel an issue personally. The Yale-George Mason poll found a record 72 percent of Americans responding that the issue of global warming is “personally important” to them. That figure is up by nine points from the previous poll last March, and the first time since November 2008 that the percentage reached 70.

Record-high acknowledgment that climate matters, though still short of a slam-dunk. One of many striking charts in the Yale-George Mason report.

The downside to this figure is not just that 28 percent called global warming either not too important or not at all important, but that it took a full decade to regain the high ground of the 2008 poll. Though the report doesn’t include cross-tabs by political allegiance, it’s virtually certain that the persistent “not important” shares, especially from 2010 through last March, reflect the tendency of many Republicans, knowing that party identity is partly centered around extractionism and climate denialism, to reject the reality of climate change.

The poll did not ask policy questions, so it has no new data on carbon tax acceptance. This is probably just as well in light of the fluid state of opinion on carbon taxing, not just among the public but on the part of climate advocates. Whether or not a carbon tax is included among Green New Deal proposals being aired in the activist community and Democratic Party circles could help determine what future polling has to say about Americans’ acceptance of carbon taxes as denialism and unconcern lose their hold on public opinion.

Ocasio-Cortez Backs “Externality Pricing” During MLK Celebration

This post was has been updated to include a video link to Rep. Ocasio-Cortez’s extended conversation with writer Ta-Nehisi Coates and to provide the full quote of her endorsement of externality pricing.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the newly installed Congressmember from parts of Queens and the Bronx in New York City and the Democratic Party’s brightest new star in at least a generation, breathed fresh life into carbon taxing today from the stage of Manhattan’s fabled Riverside Church. Her remarks came during “MLK NOW,” a day celebrating Martin Luther King’s life and work combating militarism, materialism and white supremacy.

The commemoration was held six days after what would have been Dr. King’s 90th birthday, and more than a half-century after King ascended the Riverside pulpit to deliver his prophetic speech, Beyond Vietnam. Ocasio-Cortez alluded to the condemnation that rained down on King in the last year of his life for demanding the U.S. end the Vietnam War, saying “King didn’t just sacrifice his life; the way he lived his life was a sacrifice.”

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, speaking at Riverside Church in New York City, Jan. 21, 2019.

Ocasio-Cortez spoke in an extended on-stage conversation with renowned author and public-intellectual Ta-Nehisi Coates. Their full, 51-minute conversation may be viewed on YouTube (from the 14:00 mark to 1:05:30). Covering a broad range, the two discussed her call to raise the marginal tax rate on high income to 70 percent; “the case for reparations” — a matter that Coates brought to prominence in his 2014 Atlantic Monthly article with that title; and her conviction that what’s immoral about billionaires is not them as individuals but the system that allows and valorizes them.

Toward the end, Ocasio-Cortez steered the conversation to the climate crisis and called for “structuring an economy that is sustainable, where “the externalities of the damage of some industries or markets get internalized.” (at 1:00:56, emphasis added) There, in a nutshell, is the polluter-pays principle that underlies the idea of taxing carbon emissions.

The remark is noteworthy given Ocasio-Cortez’s prominence in advocating a Green New Deal, the idea of a wartime-style mobilization of government and business to build a net-zero-carbon economy over the next decade. We at the Carbon Tax Center believe that a robust carbon tax must be a pillar in any Green New Deal, not just as a “pay-for” but as a means to incentivize the massive changes in behavior, investment and societal defaults necessary to move U.S. society off fossil fuels.

On a personal note, the Riverside Church event was my first time seeing Ocasio-Cortez in person and hearing her speak extemporaneously and at length. What I saw, heard and felt easily surpassed the hype. Throughout her 50 minutes on stage, she came off as grounded, determined, forceful, informed, fluent and thoroughly conversant with the history and vocabulary of U.S. popular protest and social movements. And, somehow, commanding yet modest.

Not long after Ocasio-Cortez began, I whipped out my pen and pad and jotted down some of her most telling sentences as best I could. Here are some, concluding with the “externality” quote.

Activism is part of governance.

People think of elective office as a leadership position [yet] the real leaders are the writers, journalists, activists and artists.

Marginal tax rates are an economic question, but they’re also a moral question.

“Where do we draw the line in material excess is a question that King asked, that Gandhi asked.” — Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

Where do we draw the line in material excess is a question that King asked, that Gandhi asked.

We think of reparations as repairing the damages of slavery, but it’s also the reparation of the damages from the [exclusionary] New Deal and redlining.

I use social media as much to listen as to speak.

We don’t have to compromise our values to find common ground with other people.

The world is going to end in 12 years [due to climate change] and you’re worried about how we’re going to pay for it?

Until we all start pitching in and holding people accountable, I’m going to let [our enemies] have it.

There was once almost a consensus among our great thinkers [including] Einstein and Dr. King that capitalism had an expiration date.

Democratic Socialism means introducing modes of democracy beyond just elections and throughout the economy . . . structuring an economy that is sustainable, where the externalities of the damage of some industries or markets get internalized.

In bookends to her remarks, Ocasio-Cortez explained why she’s not fearful about taking strong stands. As a Puerto Rican teen in a white suburban high school, she said, she learned not to pay attention when someone tried to put her down. Now, in Congress, she sees herself not as an individual seeking to rise in politics who must practice caution but as a participant in an unstoppable movement to advance democracy and create a just society.

Note: Dr. King’s 1964 speech referenced in my tweet may be found here.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- …

- 170

- Next Page »