Robinson Meyer, commenting on three linked articles by the Global Carbon Project, in 5 Big Trends That Increased Earth’s Carbon Pollution, The Atlantic, Dec. 3. The quote is from the project’s article in Nature Climate Change (links are in the Atlantic article).

The Climate Moment — and Movement — Have Passed Mike Bloomberg By

I’m rarely without one of my own bikes. But lately, dicey weather and scheduling issues led me to add Citibikes to the mix. And during each hassle-free ride I marveled anew that since 2013 the City of New York, home to some of the world’s most contested streets, actually cleared out space for the bicycle docks and racks.

The man who faced down the skeptics — of whom there were many — and saw bike-sharing through? Michael Bloomberg, during his third and final term as mayor.

Earlier this year, Albany legislators wrote language into the state budget that in 2021 will launch the world’s most ambitious congestion-pricing plan in NYC. As visitors to this site know, I fought for this groundbreaking program, as pamphleteer and traffic-modeler. I recognize that congestion pricing’s passage was made possible by a host of advocates in and outside government. High among them was Bloomberg; his bold though unsuccessful push for traffic tolls a dozen years ago laid the ground for this year’s win.

As mayor, Bloomberg instituted a slew of measures, many of them controversial, that have made New York more healthful and prosperous. All deserve to be counted as green achievements because they have attracted and kept businesses and residents in our dense and efficient, hence low-carbon city. He also, in 2007, called for a U.S. carbon tax, becoming perhaps the most prominent American to back straight-up carbon taxing rather than the convoluted cap-and-trade schemes beloved of mainstream environmental groups back then. More recently, Bloomberg’s post-mayoral contributions to the Sierra Club’s “Beyond Coal” campaign helped shove scores of carbon-spewing coal-fired power plants into early retirement — a certified climate win.

Knowing all this, you might ask why, in an interview with Inside Climate News, I chose to pour cold water on the idea of Bloomberg as a 2020 climate candidate . . . going so far as to call him “the perfect climate candidate for 2007.” (My epithet wrapped ICN’s story yesterday, Bloomberg Is a Climate Leader. So Why Aren’t Activists Excited About a Run for President?)

Why? Because, as I told ICN, I believe that extreme wealth stands in the way of the radical transformations the climate emergency requires.

If, as I believe, rapid and full decarbonization must entail fundamental changes in how humans live and work and organize, then everyone’s lives must transform. It won’t wash for the super-wealthy to go on leading lives of unbounded privilege — luxuriating on their yachts, globetrotting among their mansions, helicoptering from one island or summit gathering to another — burdened only by carbon fees on their huge footprints.

Bloomberg is of that class. That he has greater awareness than his peers is to his credit. But so long as he wields and personifies extreme wealth, he cannot be the avatar of transmuting it into productive use.

In the U.S., new work by the U-C Berkeley economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman suggests that taxes on extreme wealth and financial transactions, supplemented by increases in estate taxes, marginal income tax rates, capital gains and corporate taxes, will be able to generate trillions of dollars from the wealthiest American households. Those revenues, not carbon tax revenues, must be the funding source of the vast amounts needed to pay for the Green New Deal energy programs.

Unfortunately for Bloomberg’s presidential candidacy, fundamental climate solutions can’t co-exist with extreme wealth.

What I meant by my “Bloomberg 2007” comment is that, with climate damage already skyrocketing and emissions still rising, we’ve shot past the point when a carbon tax could have been the primary policy engine to slash U.S. and other nations’ carbon emissions quickly enough to keep the rise in global temperatures under the presumed 1.5ᵒC ceiling.

That wasn’t so in 2007, the Carbon Tax Center’s inaugural year as well as when Mike Bloomberg vaulted to the front of the valiant band of political leaders and advocates calling for robust carbon taxing. But now, a dozen years on, the climate crisis is too dire, and economic inequality too extreme and enraging, for carbon taxing to function as the main ticket out of climate catastrophe.

In the coming months, the Carbon Tax Center will be retooling our program to reflect our new view that the path to decarbonizing the U.S. economy lies in a Green New Deal-inspired infrastructure and investment program funded by taxes on extreme wealth and supported by a carbon tax. Please watch this space.

As for Mike Bloomberg, we acknowledge, with deep gratitude and genuine respect, his past vision and leadership and thank him for his service. The torch is passing to new leadership that will attack the power to lord and the power to pollute at the same time.

March 2020 addendum: On March 1, just before Bloomberg ended his candidacy, NY Times climate reporter Lisa Friedman posted an unusually substantive and nuanced assessment of his climate record, Fighting Coal Was Supposed to Lift Bloomberg. Here’s Why It Didn’t. The money quote is from Paul Bledsoe, a strategic adviser at the Progressive Policy Institute:

Bloomberg is a victim of the climate debate moving much faster than the positive realities he helped shape on the ground. In particular, his focus on coal seems passé now that the target of the left is natural gas.

The next U.S. president can save more lives and better improve human health by slowing climate change than by improving health insurance.”

New York Times columnist David Leonhardt, in The Most Pressing Issue for Our Next President Isn’t Medicare, October 27.

“In terms of CO2’s greenhouse effect, today’s world is already as far from that of the 18th century as the 18th century was from the ice age.”

What Goes Up, The Economist, Sept 21-27 (subscription required).

IMF Adds Populist Twist to Carbon-Tax Push

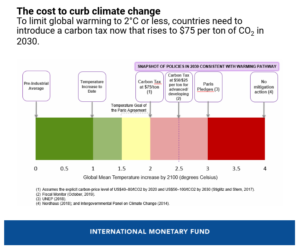

The International Monetary Fund is endeavoring to put carbon taxing front-row center in climate policy with a new report, How to Mitigate Climate Change. (Link to IMF blog post about the report, here; link to report executive summary, here; link to entire 30-p. report, here.)

“Carbon taxes levied on the supply of fossil fuels in proportion to their carbon content are the most powerful and efficient . . . of the various mitigation strategies to reduce fossil fuel CO2 emissions,” says the report, “because they allow firms and households to find the lowest-cost ways of reducing energy use and shifting toward cleaner alternatives.”

Nothing new there. What’s noteworthy in the report released today by IMF are three things:

Nothing new there. What’s noteworthy in the report released today by IMF are three things:

First, the report quantifies emission reductions for three different levels of carbon taxes: $25/ton, $50/ton and $75/ton. The results, shown at left, reveal both carbon taxing’s power and its limits. The projected reductions from the $75/ton tax are substantial, surpassing 40 percent of emissions for the world’s #1 and #3 current emitters, China and India. Yet those reductions are vis-a-vis 2030 emissions, not current levels. Moreover, they fall far short of the needed contractions for meeting the nominal IPCC target of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Centigrade, as the graph below demonstrates.

Second, the report eschews the disastrous conflation of the principal carbon externalities (climate damage and air pollution) as subsidies — a misguided framing that marred the otherwise exemplary (and pro-carbon tax) 2014 IMF report, Getting Energy Prices Right. That language furthered the false narrative that governments need not tax fossil fuels to slash CO2, since they would only need to zero out their fossil fuel subsidies; in fact, the “subsidies” were largely the failure to tax in the first place.

Last, and perhaps most intriguing, the report takes the bold step — bold for an establishment icon like IMF — of casting France’s Gilets Jaunes (yellow vest) movement not as know-nothings protesting a piddling rise in the price of diesel, but as a rising up against the privilege to pollute enjoyed by the rich:

In France, the rapid ramping up of a similar [to Sweden’s] carbon tax was suspended in 2018 at $50 a ton, following public backlash against the perceived unfairness of the tax, which was introduced at the same time as broader tax reductions seen as benefiting the wealthy. (IMF at pp 13-14)

IMF label is a misnomer. Carbon taxes aren’t a cost since each dollar of tax creates a dollar of revenue that society can use to mitigate higher fuel costs, reduce other taxes or invest productively.

It’s good to see IMF address the political dimensions of energy pricing. Better still that this bulwark of global capitalism is warming to the view of journalist Christopher Ketcham, who embedded with the yellow vesters during their Paris protests last winter and discovered that they are intent on toppling both wealth and carbon. (Ketcham’s revealing portrait of the protest movement, What the Gilets Jaunes Really Want, appears in the August issue of Harper’s.)

The Washington Post’s Chris Mooney scooped the IMF report earlier today with a solid story, The world needs a massive carbon tax in just 10 years to limit climate change, IMF says. While a $75/ton charge by 2030 can’t quite qualify as a massive carbon tax level, such a levy applied to the entire world would indeed have massive scope and impact.

Not for the first time, the Fund has invested its expertise and prestige in prodding governments across the globe to move quickly and decisively toward taxing carbon emissions. It’s time for the rest of us to join the push.

Message to Warren: The Light-Bulb Revolution Teaches that Energy Efficiency Doesn’t Mean Sacrifice

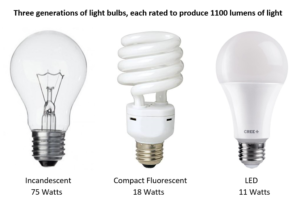

Forty years ago, the only “screw-in” light bulbs were incandescent. Little-changed since their invention in the late 1800s, “Edison” bulbs were cheap, disposable and staggeringly inefficient. “Small electric heaters that give off a bit of light” is how someone once described them. Coal guzzlers, given how much electric current they drew.

Around twenty-five years ago, compact fluorescent light bulbs became widely available and reasonably affordable. CFL’s were marketed as offering the same illumination as incandescents for far less power, enabling them to quickly pay off their higher initial costs with the saved electricity. But they were unwieldy — taking a bit too much time to reach full brightness, for example — their light was unattractive, and the bulbs contained mercury, rendering them, for some people, off-putting. CFL’s were a climate solution, but far from an ideal one.

Finally, a decade or so ago, LED bulbs came on the market. More efficient than CFL’s, non-toxic, long-lasting and beaming brilliant light through dozens of tiny light-emitting diodes, LED’s are about as perfect a means of artificial illumination as can be imagined. Unsurpisingly, consumers ate them up.

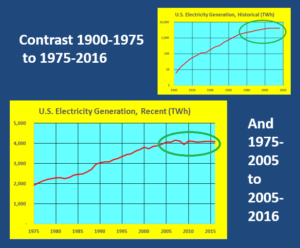

The widespread switch from incandescents to CFL’s and ultimately to LED’s is a big reason that starting in 2005 and lasting for more than a decade, the U.S. economy was able to hold total electricity consumption constant even as output of goods and services grew 20 to 25 percent. So unprecedented was this “decoupling” of electricity from economic activity that we at CTC produced a report, The Good News, celebrating it and explaining it. (Electricity usage did jump nearly 4 percent last year — Trumpism in action, perhaps? — but thus far in 2019 it’s down 2 percent.)

To be sure, more-efficient light bulbs weren’t the only factor holding down power demand. Penetration of digital tech in manufacturing and energy management also helped, as did the emergence of a robust business sector to harness energy efficiency. Ditto the structural shift from heavy manufacturing to service industries, along with a shift to urban living and delayed family formation, which resulted in smaller dwellings with fewer appliances (with the appliances themselves gaining in efficiency due to increasingly ambitious standards).

The LED revolution has played a big part in flattening U.S. electricity usage, which since 2005 has done more than even wind and solar combined to hold down carbon emissions.

Nevertheless, the revolution in lighting offers the perfect rebuttal to the notion that energy efficiency — the linchpin of quickly eliminating fossil fuels from our energy supply — somehow entails sacrifice. LED’s are superior to incandescents along every criterion, most critically in producing the same or better lighting with more than an 80 percent saving in electricity. And if they cost more to buy, many utilities offer “demand-side” programs to help cut the customer price.

Which makes Elizabeth Warren’s handling of the light-bulb question during yesterday’s climate debate so frustrating. Yes, there was such a question, and it offered a fabulous opportunity to push back against the notion that energy efficiency entails Americans sacrificing. Alas, the opportunity was missed, as can be seen in this edited version of Sen. Warren’s exchange with moderator Chris Cuomo:

Cuomo: Do you think the government should be in the business of telling people what kind of light bulb they should buy?

Warren: Oh come on, give me a break. This is exactly what the fossil fuel industry hopes we’re all talking about. That [climate] is “your” problem. They want to stir up a lot of controversy around light bulbs, around your straws and around your cheeseburgers when 70% of the pollution and of the carbon we’re throwing into the air comes from three industries. Why don’t we focus there? It’s corruption. It’s these giant corporations that [are] making big bucks off polluting our earth.

To be fair, Warren’s full answer (included here, at the end) had more nuance than this excerpt. She took pains to say “There are a lot of ways … to change our energy consumption. And our pollution. And God bless all of those ways.” But her attempt to deflect Cuomo’s question backfired, because she let his implicit equation of efficiency with deprivation go unchallenged.

Moreover, Warren’s “70% of the pollution comes from three industries” notion is grossly misleading. Yes, it’s the electric power plants, not the person at home, that spews carbon; but cutting demand so those plants slow and stop their emissions during the transition to solar panels and wind turbines is going to require redoubling our efficiency efforts (emulating California would be a great start). Which means continually ratcheting upward efficiency standards for lighting, appliances and industry.

If we can’t proudly defend not just lighting efficiency but the 40-year collaboration of engineers, environmentalists and regulators that painlessly delivered efficiency to the entire U.S. appliance sector (refrigerators, air-conditioners, dishwashers, heat pumps, etc.), how are climate hawks going to champion the necessary choices that may actually entail some sacrifice, such as flying less, driving less mindlessly, welcoming urban density and transit-oriented development, and so on?

That is why Warren’s punt on the light-bulb question hurts. And the harm has been exacerbated by the enthusiastic reaction of prominent left-green commentators. Rebecca Leber at Mother Jones congratulated Warren for “cutting through the dumbest climate argument,” despite the fact that Warren didn’t cut through the argument, she ducked it. At Vox, Li Zhou wrote that “Warren’s response speaks to how the fossil fuel industry [is] eager to shift the framing of subjects like light bulbs and paper straws in order to put the focus on consumer choice and deflect from the larger issue of reducing pollution,” a take that disconnects the vital matter of electric generation pollution from the demand that helps give rise to it.

Sure, it’s politically attractive to put the entire onus for climate catastrophe on giant corporations. But actually tackling and overcoming the climate crisis will require even more fundamental change than dismantling Big Oil.

Following is Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s Q&A with moderator Chris Cuomo on light bulbs, in the Sept 4, 2019 CNN Climate Town Hall

https://www.cnn.com/videos/politics/2019/09/04/bernie-sanders-sot-trump-stance-climate-cnn-town-hall-vpx.cnn/video/playlists/climate-change/

Chris Cuomo — The president announced plans to roll back energy saving lightbulbs and he wants to reintroduce four different kinds which I am not going to burden you with but one of the ones is the candle shaped ones and those are in favor for a lot of people. But do you think the government should be in the business of telling people what kind of light bulb they should buy?

Elizabeth Warren — Oh come, on give me a break! (Sighs) You know…

CC: Is that a “yes”?

EW: No… Here’s… Look, there are a lot of ways that we try to change our energy consumption. And our pollution. And God bless all of those ways. Some of it is with lightbulbs, some of it is with straws and some of it… Dang!… is with cheeseburgers. Right? There are a lot of different pieces to this and I get that people are trying to find the part that they can work on and what can they do. I’m in favor of that and I’m gonna support that. But understand, this is exactly what the fossil fuel industry hopes that we are all talking about.

(Applause)

EW: That’s what they want us to talk about. That this is “your” problem.

(More applause.)

EW: They want to be able to stir up a lot of controversy around your light bulbs, around your straws and around your cheeseburgers when 70% of the pollution, and of the carbon we’re throwing into the air, comes from three industries. And we can set our targets and say by 2028, 2030, and 2035, no more. Think about that. Right there. Now, the other 30% we still gotta work on. Oh no, we don’t stop at 70%. But the point is that’s where we need to focus. And why don’t we focus there? It’s corruption. It’s these giant corporations that keep hiring the PR firms and everyone has fun with and gets it all out there so that we don’t look at who’s still making the big bucks off polluting our earth. The time for that has passed. We have a chance. A chance left in 2020 to turn this around but we are running out of time so we’ve got to do this in 2020 and that means the first thing we’ve gotta do is that we have to attack this corruption head on in Washington and say enough of having the oil industry and the fossil fuel industry write all of our laws in this area. No more!

Transcription by CTC intern Rohan Kremer Guha

You shouldn’t be able to externalize these costs. That’s the problem with fossil fuels.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, at the Democratic presidential candidates’ climate debate, Sept 4. [link TK]

The morning after he dropped out, Inslee announced he would seek a third term as governor of Washington. A number of journalists tweeted that he would do well as the next Democratic EPA administrator. I disagree. The EPA’s ambit is too narrow, and climate change too sprawling, for Inslee’s time and talents. If the 2020 Democratic nominee, whoever it is, really wants to tackle climate change as their own plan discusses it—as an issue afflicting the whole economy—then they’ll need to show that someone in their administration can tackle it at the whole-economy level. They’ll need to put their money, in other words, where their Medium post is. They could start by calling Jay Inslee. He would make an excellent vice president.”

Robinson Meyer, in For Democrats, When Does Climate Change … Actually Matter?, The Atlantic, August 22.

Germany’s Greens recently learned from a study of voter concerns in Europe that the second-most-popular statement among far-right voters, after one on limiting migration, was this: ‘We need to act on climate change because it’s hitting the poorest first and it’s caused by the rich.’

New York Times, Greens Aim to Make Climate a Bread-and-Butter Issue, July 14.

The Divestment Diversion

The Carbon Tax Center has had qualms since day one about campaigns to compel institutions to divest from their fossil fuel holdings. The morality is great, but impact is lacking.

“Divestment can’t loosen the fossil fuel stranglehold without a carbon tax,” we wrote in a photo caption in our first stand-alone post on divestment four years ago.

“Divestment can’t loosen the fossil fuel stranglehold without a carbon tax,” we wrote in a photo caption in our first stand-alone post on divestment four years ago.

Today, with a broadened outlook, we would write that divestment can’t loosen the fossil fuel stranglehold without a Green New Deal-level massive investment in decarbonization, with a robust carbon tax playing a major contributory role — a position we outlined in a post earlier this year, Carbon Tax Advocates Should Embrace a Green New Deal.

Our 2015 post outlined why fossil fuel divestment is a dead end:

Divestment by socially responsible investors, universities and even governments won’t starve capital flows to fossil fuel corporations anytime soon. That’s because in a global market, every share of stock we activists dutifully unload will be snatched up in milliseconds by some trader who can bank on humanity’s continued dependence on fossil fuels to continue generating profits. (emphasis added)

Why bring this up now? Because we just stumbled across an illuminating 2018 interview with U-Mass economist Robert Pollin, a prominent climate academic-activist and co-author of a detailed financial analysis of fossil fuel divestment impacts. The interview, posted at Truth Out in May 2018, is entitled, Are Fossil Fuel Divestment Campaigns Working? A Conversation With Economist Robert Pollin. Sadly but unsurprisingly, Pollin concluded in his analysis, also from 2018, that they aren’t.

Here’s the key excerpt. The questioner is C.J. Polychroniou, a Truth Out contributor and political economist-scientist. We added boldfaced type, for emphasis.

Q: One approach that has become quite popular in recent years is the strategy of divestment. However, the recent study you coauthored with Tyler Hansen questions the effectiveness of the strategy of divestment in reducing carbon emissions. How did your study come to that conclusion?

A: In this new research paper, Tyler Hansen and I concluded that divestment campaigns have not been especially effective as a means of significantly reducing CO2 emissions, and they are not likely to become more effective over time. Our study includes both an analysis of the available data on global divestment patterns as well as a formal statistical modeling exercise that evaluates the impact of divestment events — such as when the New York City pension fund decided last January to sell off all of their fossil fuel company holdings — on the stock market prices of fossil fuel companies.

We found two basic things from this research. First, to date, we found the total level of divestment commitments to be at about 0.7 percent of total global private fossil fuel assets (assets committed to divestment are at about $36 billion while total global private fossil fuel assets are at $4.9 trillion). Second, we found no evidence that any divestment actions, including the recent New York City pension fund decision, has [sic] had any significant negative effect on the stock prices of fossil fuel companies.

The basic problem with the strategy is straightforward. Ethically motivated owners of fossil fuel stocks and bonds — such as the New York City Council — do certainly have the power to sell these assets as a statement of principle and act of protest. But this act of protest will have no direct impact on the operations of the fossil fuel companies as long as investors who are profit-seekers, as opposed to being motivated ethically, are willing to purchase the stocks and bonds that ethically motivated investors have put up for sale. Indeed, the core divestment strategy of selling fossil fuel assets is, at best, incomplete until one addresses this question: Is there somebody out there still willing to purchase these fossil fuel assets, and if so, and at what price? The answer is, yes, there are plenty of people ready to purchase shares of fossil fuel companies as long as they can profit by owning these shares.

In addition, the profit opportunities from owning oil, gas and coal company stocks are not diminished through the divestment-led sales per se. This is because divestment per se does not affect either how much it costs to produce fossil fuel energy or how much consumers are willing to buy. In theory, divestments might be capable of pushing down stock market prices of fossil fuel companies. But it is also likely that any such impact on stock prices is going to remain negligible as long as profit-seeking investors continue to make money. And they will continue to make money unless we succeed in either raising costs of producing fossil fuels or limiting how much fossil fuel energy consumers can buy.

Pollin hastens to add, as we did in 2015, that he and his co-author Tyler Hansen “greatly respect the accomplishments of the divestment movement”:

[Divestment campaigns] enable activists to fight for goals that can be clearly articulated and achieved within the institutions and communities in which they work and live, as opposed to attempting to influence public policies where the decision-making process is more remote. Divestment campaigns also have a demonstrated record of success in raising consciousness as to the urgency of dramatic action on climate change, and the need to confront the power of the fossil fuel industry as the single greatest barrier to advancing a viable climate stabilization project.

Despite these substantial accomplishments, we nevertheless conclude, based on the findings we present here, that most efforts now devoted to divestment campaigns would be better spent on more direct efforts to drive down fossil fuel consumption and CO2 emissions. We simply don’t have time to lose in pushing as effectively as possible on the fundamental goal which we cannot lose sight of — which is to drive CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions down to zero as quickly as possible. We need to remember that, at best, divestment is a means to an end, with the end itself being eliminating emissions.

There’s a wealth of supporting analysis in the Pollin-Hansen paper (here’s link, again). But the takeaway remains that divestment is primarily a tool for movement-building rather than carbon-busting. Climate laggards like New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio who wrap themselves in the mantle of fossil-fuel divestment are just green-washing.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- …

- 170

- Next Page »