Komanoff: The Time Has Never Been More Right for a Carbon Tax (U.S. News)

Search Results for: komanoff

Komanoff asks: If efficiency hasn’t cut energy use, then what?

Komanoff asks: If efficiency hasn’t cut energy use, then what? (Grist)

Komanoff: Senate Bill Death = Win for Climate

Komanoff: Senate Bill Death = Win for Climate (The Nation)

Q&A: Charles Komanoff

Q&A: Charles Komanoff (Mother Jones)

‘Hochul Murder Mystery’ Highlights Carbon-Pricing Hurdles

This post, a teeth-clenched corrective to my late-April Diary of a Transit Miracle, was necessitated by Kathy Hochul’s jaw-dropping “indefinite pause” (read: cancellation) of the congestion pricing program she had supported since stepping into the governorship of New York State in August 2021. Like “Diary,” it first appeared in The Washington Spectator, which posted it on June 11 as Hochul Murder Mystery.

That title placed the spotlight on Hochul, whose decision it was to abandon New York City’s congestion pricing plan; on murder, because her delay jeopardizes the precariously perched program to charge drivers to the congested (and transit-rich) heart of the NY metro area even a fraction of the added travel delays their trips impose; and on mystery, owing to the bizarreness of her abrupt turnabout.

Six days on, however, there’s a growing sense that Hochul simply panicked . . . that her belief in (and grasp of the rationale for) imposing a robust fee on private car trips to the Manhattan central business district was too slender to withstand the criticism from motorists for bringing congestion pricing to fruition.

What’s also growing, though, is the pushback to Hochul’s peremptory, unilateral decision. Not just “the usual suspects” — transit proponents, policy wonks and urbanists — but also business interests, infrastructure contractors and good-government advocates — are mounting a sustained counterattack intended to restore the congestion pricing timeline (it had been on track to “go live” on Sunday, June 30). While that outcome may be out of reach, the final chapter in New York’s congestion pricing saga has not necessarily been written.

Nevertheless, Hochul’s pullback underscores just how hard it remains to bring about meaningful externality pricing in the United States. The high hopes we at Carbon Tax Center had invested in NYC congestion pricing as a pacesetter require that we be candid: the setback to carbon pricing, should it stand, will be considerable.

— C.K., June 17, 2024

Note: Other than the photo montage, which we have reproduced from The Spectator, graphic elements here are new.

Photo montage: Riders Alliance

Not two months ago, in a brief history of how congestion pricing triumphed in New York, I canonized New York Governor Kathy Hochul, placing her alongside transportation legends Bill Vickrey (Nobel-winning traffic theorist), Ted Kheel (transit-finance savant), and the upstart Riders Alliance that in 2019 achieved what previous campaigners could not: legislation mandating a revolutionary new toll system that would weed out enough car trips to Manhattan’s core to cut down on endemic gridlock while generating revenue to enable generational expansions of subway and bus infrastructure.

Diary of a Transit Miracle, the Spectator titled that piece. Hochul, I wrote, had proved herself “a resolute and enthusiastic” congestion pricing backer. “Her spirited support,” I said, “became the decisive ingredient in shepherding congestion pricing to safety.”

Twelve days after announcing her rescission of congestion pricing, Hochul is still being ferociously “dragged” on social media. Another tweet noted that “Hochul’s decision to blow a $15 billion hole in the MTA’s budget [means] she will get blamed for every single mass transit problem going forward in a city where the majority of people take public transit.”

The story, though infuriating to urbanists, climate advocates and foes of big-city car-dominance who for decades had looked to New York congestion pricing for deliverance, is also juicy. It’s hard to recall a public policy story with as many tentacles as this one.

Let us count the ways.

Hochul’s late-in-the-day reversal obviously is a New York story. With congestion pricing, the nation’s largest city, possessor of a singular global brand, was poised to recapture its pre-eminence in progressive, bold innovation. Instead, its literal engine ― its subway system ― has been jilted at the altar.

It’s also a dystopian governance story, as befits the unilateral monkey-wrenching of a policy forged by thousands of individuals, agencies and organizations over years and, for some, decades. As livable-streets journalist Aaron Naparstek wrote on Twitter, Hochul and her Congressional consiglieres “aren’t just undermining congestion pricing, they’re discrediting the Democratic Party and they’re undermining faith in government and democracy.” New York Times editorial writer Mara Gay lamented that “Americans didn’t need a reason to feel more cynical about politics. But Gov. Kathy Hochul of New York has delivered one.”

And of course, it’s a traffic and transit story. How will New York City solve or at least mitigate its habitual, maddening gridlock, which, notwithstanding post-pandemic office malaise, was revealed last week by city transportation officials to have grown even more strangulating than it was in 2019.

Answer: it won’t. Without congestion pricing’s stiff but fair $15 toll to drive into Manhattan south of 60th Street during most hours, alternative measures to reduce New York’s staggeringly costly traffic gridlock will invariably succumb to the dreaded “rebound effect.”

Sign at June 12 rally across from Hochul’s midtown office. An estimated 800 New Yorkers marched for congestion pricing, chanting “Safer streets, cleaner air, Governor Hochul doesn’t care.” Photo by author.

And how will Hochul and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority she commands come up with a billion-dollar-a-year revenue stream to cover the interest on $15 billion in long-awaited investments in subway station elevators, digital train signals, and clean, electric buses?

Answer: they likely won’t. In a chessboard win for congestion pricing proponents, legislative leaders last week refused to rubber-stamp Hochul’s wished-for hike in the Payroll Mobility Tax, leaving her with no means to fund the new transit improvements, and putting at risk thousands of jobs in upstate factories as well as downstate. With congestion pricing the only apparent way to pay for these investments, the resistance stays alive.

Did I say resistance? The widespread pushback to the governor constitutes yet another tentacle to the story. If Hochul thought that protests over her surprise cancellation would peter out, she was badly mistaken. What began as public astonishment quickly turned to upset and grew to outrage, not just for its transit and traffic consequences but for its sheer stupidity (per climate-conscience Bill McKibben) and cowardice and cravenness (per congestion pricing campaigner Alex Matthiessen).

Nor is the rage confined to transit wonks and bike advocates. It is being expressed by the transit construction and engineering companies; by business leaders and real estate interests; by the Daily News’ editorial board as well as the Times’; by the unquenchable Families for Safe Streets who since 2018 have put their bodies on the line to spare future bereaved mothers; by urbanists who hoped other cities would follow in New York’s footsteps; and by “supply side progressives” desperate for America to actually address urban and suburban gridlock as well as housing and climate.

The fury at the governor shows no signs of abating. Midway through writing this article I attended a Riders Alliance protest in East New York where Hochul was derided as Congestion Kathy and Governor Gridlock and her face photoshopped on a faux Daily News headline, “Hochul to City: Drop Dead. Gov. Betrays Millions of Riders.” Every hour, it seems, brings word of a new demonstration, another rally, another elected official and civic leader resolving to harass and if need be break Kathy Hochul to put congestion pricing back on track.

Hochul’s action is also a car culture story. Though the city’s car-besieged and transit-rich Manhattan core is perfectly suited for congestion pricing, New York remains part of the United States and thus under the sway of mercenary auto and oil interests. Many of the city’s long-immiserated straphangers, moreover, aspire to car ownership and bristle over tolls they might someday pay, even though few working-class residents of Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island or the Bronx routinely motor to the congestion zone. Perhaps that is why the subway improvements that the tolls would pay for have yet to resonate with most “everyday” New Yorkers.

The distemper over the governor’s last-minute cancellation isn’t subsiding.

As well, New York’s political class is subway-avoidant and car-besotted, making them kissing cousins to suburban interests whose car windshields render them immune to transit’s value, except perhaps to keep others from clogging “their” road space. That the political ramifications eluded Gov. Hochul only adds spice to the story. That Manhattan and New York City as a whole couldn’t, last week, defy America’s “dominant car culture,” as the Times wrote in its Saturday editorial, is yet another sad aspect of the story.

We come now to the biggest and most puzzling piece of the Hochul congestion pricing saga: Why did she do it?

Why, after uttering nary a negative word about congestion pricing in her thousand days as governor, did she fold with a mere 25 days to go? Why, after extolling congestion pricing repeatedly and evincing genuine pleasure in being its tribune, did the governor move to murder it?

The standard explanation is that key national Democrats, most notably Brooklyn Congressmember and House Speaker-in-waiting Hakeem Jeffries, and perhaps senior White House officials as well, ordered Hochul to ice the June 30 launch to tamp voter defections in borderline House districts. This account is plausible if misguided, given that the four-month interval from June 30 to November 5 afforded ample time to “reset the default,” as Stockholm showed after its 2007 plunge into congestion pricing. The toll’s ostensible unpopularity would have ended up in the proverbial rearview mirror.

Yet these electoral concerns don’t fully add up. Any politician worth their salt knows not to abruptly reverse course on hot-button issues. And while altered circumstances can justify altered policies, no substantive change suddenly roiled New York’s transportation patterns, transit needs or economic vulnerabilities. Indeed, the governor’s fumbling attempts at justification have convinced no one.

Perhaps Hochul, an upstater and baby-boomer, was too ensnared in car culture to believe her own congestion pricing rhetoric. Perhaps campaign cash from automobile dealers moved her needle. Maybe she panicked and lost the words to tell Jeffries that helping him would destroy her political viability, end of conversation.

NYC Comptroller Brad Lander, a staunch supporter of congestion pricing, at a June 12 rally opposite City Hall, announcing litigation to invalidate Hochul’s tolling cancellation. Photo: Dave Colon, Streetsblog NYC.

Whatever caused Hochul to abandon congestion pricing, her blunder is of spectacular proportions, or so it appears to this city dweller. The prospective upset to drivers ― and not all drivers, insofar as some regarded the tolls as a means to speed their commutes ― seems almost quaint next to the actual rage of toll proponents and the derision from much of the public.

The governor can still right the ship. She could offer to lighten the toll burden around the edges, as I outlined last week. She could propose a June 30, 2025 referendum, an idea patterned on Stockholm, although who should be eligible to vote isn’t clear and could become its own bone of contention. She could cite the legislature’s hold on alternative transit funding and admit that Plan A was right all along.

The key word is admit. Not only is congestion pricing made for New York, its prolonged gestation has built it into expectations for transit finance, traffic management and the health of the city that cannot be easily unraveled.

Whatever precipitated Gov. Hochul’s loss of nerve, and whatever the consequences for her governorship and her remaining time in politics, she must reinstate congestion pricing. The need is too great, and the story too scandalous, to pretend that congestion pricing will go gentle into its good night.

Will Energy Efficiency Ever Get Its Due?

After all these years and despite so many accomplishments, measures that save energy remain U.S. climate policy’s bastard child.

Even defenders of energy efficiency sell it short. The latest instance was last Friday’s NY Times column, Give Me Laundry Liberty or Give Me Death!, by the paper’s resident polemicist, the economist Paul Krugman.

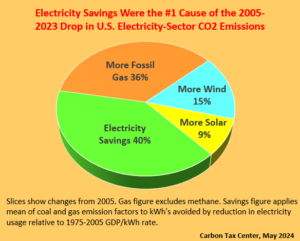

Electricity Savings’ top role in reducing electric-sector emissions is especially critical because no other sector (transport, industry, etc.) cut emissions more than marginally.

Krugman rightly savaged Congressional Republicans for contesting U.S. Energy Department efficiency standards for washing machines and other major energy-consuming appliances. His column reminds us that today’s G.O.P. never passes up an opportunity to force fossil fuels on the American public.

As Krugman noted, Republicans’ depiction of Democrats as enemies of freedom is exactly backwards: “Regulations ensuring that the appliances on offer are reasonably efficient reduce people’s cognitive burden — you might even say they increase our freedom,” by unshackling consumers from the task of weeding out inefficient (and expensive-to-run) appliances from efficient ones.

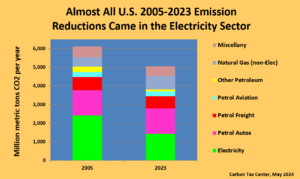

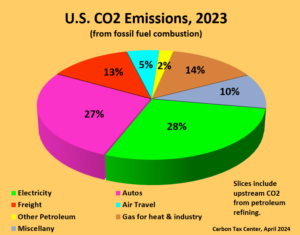

But consider what Nobel economics laureate Krugman left out: The only U.S. sector that has cut carbon emissions by more than token amounts since 2005 is electricity, furnishing a whopping 92 percent of the overall drop in emissions in 2023 since 2005. (See bar graph further below.) And energy savings, measured as kilowatt-hours that didn’t need to be generated because electricity savings curbed demand, accounted for 40 percent of electricity-sector carbon reductions — besting the 36 percent from power generators’ shift from coal to less-carbon-intensive fossil gas, and far surpassing the combined 24% share from growth in wind and solar electricity. (See pie-chart above. Details follow at end of post.)

Why are electricity savings undervalued?

Since 2005, the U.S. economy has grown by 40 percent in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. Yet over the same 18 years, U.S. electricity generation barely budged, rising just 5 percent. That is an immense change from mid-(20th)-century, when electricity usage typically grew each year by 6 or 7 percent, practically doubling every decade. This wrenching apart of electricity growth from economic growth has enabled the increased penetration of fossil gas-fired electricity and the rapid increase in wind and solar electricity to bite deeply into coal-fired power generation rather than simply add to it.

Yet energy savings are downgraded in energy and climate discourse. It’s not hard to see why.

First, energy saving is invisible. There are no ribbon-cuttings for energy-efficient buildings or appliances, no medals for low-energy lifestyles. Super-efficient houses or office buildings occasionally are singled out for praise, but what’s the visual — a low-electricity or gas bill? Or, worse, Jimmy Carter’s White House cardigan, which 1970s media held up for ridicule?

Second, saving energy lacks powerful lobbies. There’s no energy-saving counterpart to the American Gas Association, the American Wind Energy Association, the Solar Energy Industry Association, the National Coal Association, and certainly not the American Petroleum Institute, which was represented at the Mar-a-Lago dinner last week at which ex-president Trump pressed the fossil fuel industry for a billion dollars in campaign contributions. Only the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy and the Natural Resources Defense Council persistently advocate for energy effiicency, and they do so as tech experts and champions of the greater good rather than as arm-twisting lobbyists, and certainly not as bundlers of campaign cash.

Lime-green bars show CO2 emissions from electricity generation. The sole other sector with substantially lower 2023 emissions, “Other” Petroleum, shown in yellow, shrank due to natural gas’s increasing industrial-market share.

Energy efficiency and savings also suffer from a measurement problem. Implicit in measuring their climate contribution is a counterfactual: what would energy requirements and emissions have been without the energy savings?

For this post as well as predecessor posts in 2016 and 2020 I used as a baseline U.S. electricity generation if the 1975-2005 ratio between electricity growth and GDP growth had persisted. I think that was reasonable, but who’s to say? The avoided kWh’s I computed for the pie chart depend on a measuring convention that is subject to argument.

(Note that “offshoring” — the compositional shift of the U.S. economy toward services and away from manufacturing, with imports from China and other Asian countries furnishing the lost production — has also contributed to reducing the link between electricity and domestic economic activity; however, its numerical impact only accounts for a fraction of the flattening of U.S. electricity consumption over the paste two decades.)

Energy Efficiency’s Respect Deficit Is Consequential

Undervaluing energy efficiency means that energy-saving policy measures get short-changed. Efficiency standards for appliances, vehicles and buildings are insufficiently supported, enacted and enforced, leaving them vulnerable to being watered down or blocked altogether.

That’s the obvious part. More consequential is the cultural and political fallout. The short shrift accorded energy savings contributes to downplaying the demand side of energy and climate. This in turn has contributed to the unfortunate narrowcasting of climate campaigns to campaigns to block supply expansions. Measures that would curb consumption get disregarded, even though they are arguably more enduring and effective in curbing climate-damaging emissions than campaigns to halt drilling or pipelines, which largely relocate supply expansions elsewhere.

A major casualty of this narrowcasting is sidelining of carbon pricing as a serious policy contender. That’s not to say that the U.S. would necessarily have robust carbon pricing if energy savings were given their due. Rather, the marginalizing of energy savings and of carbon pricing are mutually reinforcing.

Part of the power of carbon taxing is that it operates on both the demand and supply sides of the fossil-fuel and emissions equation. (Another part is that carbon pricing complements virtually every other emissions-reducing policy or program.) Downgrading the demand aspect of our energy and climate miasma does a disservice to carbon pricing — and our climate.

Calculation Details

Calculations for this post were made in CTC’s carbon-tax model spreadsheet (2.2 MB downloadable Excel file). See Clean Electricity tab and Graphs tab. Pie-chart shares are derived by comparing 2023 and 2005 generation for solar (including distributed solar), wind and fossil gas and applying industry-average CO2 emission factors for coal and gas. Electricity-savings slice was computed by subtracting actual 2023 U.S. electricity generation from hypothetical 2023 generation if the average 1975-2005 ratio between electricity growth and GDP growth had continued through 2023, and then ascribing a per-kWh CO2 emission factor calculated as the mean of gas and coal CO2/kWh.

In crediting electricity with 92% of all 2005-2023 U.S. CO2 reductions (from fossil-fuel burning), I divided electricity-sector reductions of 983 million metric tons (“tonnes”) of CO2 by the total reduction of 1,064 million tonnes. However, the denominator is deflated by including “negative reductions” from passenger vehicles (14 million tonnes) and gas for industry (206). Even removing those sectors from the denominator, electricity accounted for 77% of total gross reductions (983 divided by 1,284). Note that these figures are shown in the Outcomes tab of CTC’s carbon-tax model.

Only a National Carbon Tax Can Halve U.S. Carbon Emissions

The first major update of CTC’s carbon-tax model since 2021 is now in the books, calibrated to 2023 emissions and the putative emissions-reducing provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act. One result stands out: Without federal legislation mandating a robust national carbon tax, the U.S. won’t come close to achieving the hoped-for 50% decline in carbon emissions (from 2005 levels) in the reasonably foreseeable future.

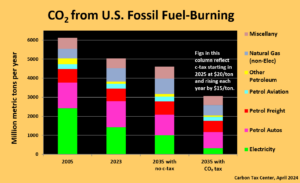

A $20/$15 carbon tax could halve carbon emissions by 2035

A national carbon tax starting next year at $20/ton and rising annually by $15/ton will cut U.S. CO2 emissions in half from 2005 levels in 2035. To halve emissions by 2030 requires $25/ton for both the starting price and the annual rises.

A national carbon price that took effect in 2025 at $20 per (short) ton and rose by $15 per ton each year would, by 2035, halve U.S. emissions of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel combustion: from 6,120 million metric tons (“tonnes”) in 2005, the standard baseline year, to an estimated 3,068 million tonnes in 2035, according to CTC’s model (Excel spreadsheet, 2 MB). That computes to a 50% reduction (rounded from 49.9%).

[NB: The site hosting the Excel file is temporarily down, please check back soon.]

But without a national carbon price, our model projects U.S. emissions in 2035 of 4,606 million tonnes. That would be just 25% below 2005 emissions, putting the country only halfway to the 50%-reduction goal in 2035. And even that piddling progress entails pushing back the customary 2030 target for halving U.S. emissions to 2035, a 5-year delay.

To be fair, the “halving by 2030” goal is generally construed to encompass not just carbon dioxide but also methane, which is regarded as lower-hanging greenhouse-gas fruit on account of its relative concentration in more easily regulatable oil and gas extraction and transport. This January methane began to be subjected to emissions pricing, through a provision of the Inflation Reduction Act mandating that emissions above a certain threshold be taxed at a rate of $900 per tonne.

But even assuming an optimistic three-fourths reduction in methane and other non-carbon GHG’s, CO2 emissions from fossil fuel-burning would have to fall by 44% from 2005 to achieve an overall 50% reduction in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. Without a national carbon price, the projected CO2 reduction from 2005 is just 17% in 2030 and, as noted, only 25% in 2035, according to CTC’s model.

Halving carbon emissions by 2030 requires a more heroic carbon tax, one starting at $25/ton in 2025 and rising annually by that amount

We also ran the CTC model to determine the carbon price level and trajectory required to halve U.S. 2005 carbon emissions by 2030 rather than 2035. Talk about a tall order! Here’s what the requisite carbon tax would look like:

- The carbon tax would take effect in 2025 (same as in the 2035 scenario).

- The initial price would be $25 per ton of CO2 rather than $20.

- The annual price rise would be the same $25/ton, rather than just $15/ton in the 2035 scenario. That means reaching triple digits in the tax’s fourth year.

- And — this is a bit technical — we’re relaxed the model assumption of the maximum annual tax rise to which the U.S. economy can fully react, from $20/ton previously to $25/ton.

It goes without saying that the present-day American political system isn’t equipped to enact and implement such an “heroic” (an adjective we prefer to “draconian”) carbon tax.

The still-lonely radical center

Prominent voices calling for carbon taxes beyond token amounts (e.g., $10 or $20 per ton with little or no increases) are precious few, not just in absolute terms but relative to the pre-2010 period in which climate concern was widespread and neither the left nor the right had been consumed by their respective demonizations: carbon pricing (on the left) or climate concern of any sort (on the right).

Indeed, here at Carbon Tax Center, we’ve traded in our web pages that previously celebrated carbon tax supporters for pages like Carbon Pricing and Environmental Justice, Progressives and Carbon Pricing, and Conservatives, all of them grouped under a heading of “Politics.” Each is essentially a litany of grievances and rejections of carbon pricing and/or climate action, period.

This chart, from CTC’s newly updated carbon tax model, shows the futility of looking for a single invention or regulation or subsidy to slash U.S. emissions. Fossil fuels suffuse our economy, making robust carbon pricing essential to achieving big across-the-board cuts.

This isn’t polarization, it’s a simultaneous disavowal by both ends of the political spectrum of the lone plausible transformational climate-preserving policy measure. (Rather than “ends” I should say “sides” of the spectrum, given that anti-pricing has spilled over from the confines of the respective extremes and now appears to occupy most of the two sides.)

Omens

Consider these two minor but telling signposts from the past week.

One was a NY Times “Sunday Review” guest essay last weekend, I’m a Young Conservative, and I Want My Party to Lead the Fight Against Climate Change, by one Benji Backer, founder-director of the American Conservation Coalition.

Alas, the essay was cut from the same generic cloth as other conservative calls to climate action. Here’s an excerpt:

We cannot address climate change or solve any other environmental issue without the buy-in and leadership of conservative America. And there are clear opportunities for climate action that conservatives can champion without sacrificing core values, from sustainable agriculture to nuclear energy and the onshoring of clean energy production.

Ho-hum. But, most strikingly, zero mention of carbon pricing — not even a nod to the revenue-neutral type such as fee-and-dividend that circumvents right-wing canards about government overreach by “dividending” the carbon revenues to households, thus correcting the market failure driving carbon emissions without “growing the government.”

So much for the right wing. On the left, I had the frustrating experience of meeting a director of an iconic American environmental organization at a public event and bonding with him over our shared dismay at the organization’s post-2016 submission to anti-carbon-pricing rhetoric . . . only to be ghosted when I tried to arrange a meet-up to possibly grow our newfound patch of common ground.

So much for dialogue in service of effective climate policy.

Can’t we bring U.S. emissions down sharply without carbon pricing?

Alas, no. U.S. emission progress perennially falls short of even modest hopes. Almost from the moment the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act — which CTC supported from the git-go — was enacted into law, it has bumped up against a calamity of transmission bottlenecks, supply-chain woes and high interest rates. Even worse, perhaps, is the legal-regulatory “default” against building almost anything, even essential elements of the clean-energy infrastructure the IRA was intended to unlock

(Just after this post went up, I came across NY Times columnist Ezra Klein and Atlantic staff writer Jerusalem Demsas’s trenchant dive into the permitting-resistance phenomenon. Their analysis traces much of today’s disabling red tape and NIMBYism to Democratic Party empathy that prioritizes concerns about marginalized constituencies over the common good. Audio version here, transcript here.)

And let’s not overlook the emergent hellspawns of energy demand like AI processing, cyber-currency computing and ever-larger SUV’s and pickup trucks driven ever more miles, all of which threaten to pile on new carbon emissions almost as fast as incumbent emissions are removed.

As we’ve argued in post after post — just scroll through our monthly archives — these and other decarbonization derailments would be greatly alleviated by the robust carbon taxes we scoped above. Pricing the climate benefits of reduced fossil fuel use into the vast array of alternatives — from clean energy to all the ways of using less — will raise their profitability and, before long, bend society’s defaults toward replacing fossil fuels.

Our updated carbon-tax model shows that U.S. carbon emissions fell by 2.3% from 2022 to 2023. If there weren’t a climate emergency, that might qualify as a decent win. But in our real, overheating world, that rate doesn’t come close to the 4.1% compound annual decline needed to halve 2005 emissions by 2035, much less the 6.9% annual emissions shrinkage required to meet the same goal in 2030.

The insufficiency of even the best-intentioned policies and programs to meet necessary carbon targets without robust carbon taxing can’t be hidden indefinitely. The carbon tax reckoning awaits.

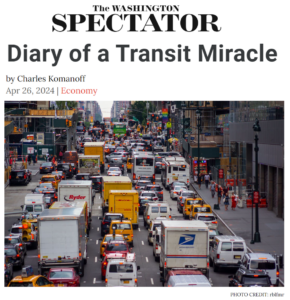

Diary of a Transit Miracle

Over the weekend the Washington Spectator published my essay, Diary of a Transit Miracle, recounting the arduous march of NYC congestion pricing from a gleam in a trio of prominent New Yorkers’ eyes at the end of the 1960s, to the verge of startup at the upcoming stroke of midnight June 30, the startup time announced by the MTA last Friday.

Landing page for this post’s original version.

I’m cross-posting it here — the third post on the subject in this space in the past 12 months (following this in December and this post last June) — because the advent of congestion pricing in the U.S. is “a really big deal,” as a number of friends and colleagues have told me in recent weeks. As my new essay makes clear, charging motorists to drive into the heart of Manhattan isn’t just a rejection of unconstrained motordom, it’s a new beachhead in “externality pricing” — social-cost surcharging — of which carbon taxes are the ultimate form.

The essay features two governors, two mayors — one of whom I served a half-century ago as a lowly but admiring data cruncher — a civic “Walter Cronkite,” a Nobel economist, raucous transit activists, a gridlock guru and yours truly, plus a cameo appearance by Robert Moses. It includes footage of the historic 1969 press conference in which Mayor John Lindsay and two distinguished associates enunciated the core idea of using externality pricing to better balance automobiles and mass transit that animated the arduous but ultimately triumphant congestion pricing campaign.

— C.K., April 29, 2024

Diary of a Transit Miracle

A miracle is coming to New York City. Beginning on July 1, and barring a last-minute hitch, motorists will soon pay a hefty $15 to enter the southern half of Manhattan — the area bounded by the Hudson River, the East River and 60th Street.

An anticipated 15 percent or so of drivers will switch to transit, unsnarling roads within the “congestion zone” and routes leading to it. The other 80 or 90 percent will grumble but continue driving. That is by design. The toll bounty, a billion dollars a year, will finance subway enhancements like station elevators and digital signals that will increase train throughput and lure more car trips onto trains.

The result will be faster, smoother commutes, especially for car drivers and taxicab and Uber passengers, who will pay a modest surcharge of $1.25 to $2.50 per trip. Drivers of for-hire vehicles will benefit as well, as lesser gridlock leads to more fares.1

The miracle is three-fold: Winners will vastly outnumber losers; New York will be made healthier, calmer and more prosperous; and that this salutary measure is happening at all, after a half-century of setbacks.

Obstacles to congestion pricing

Congestion pricing, as the policy is known, faced formidable obstacles even beyond the difficulty inherent in asking a group of people to start forking over a billion dollars a year for something that’s always been free.

Congestion pricing also had to contend with: an ingrained pro-motoring ideology that casts any restraint on driving as a betrayal of the American Dream; a general aversion to social-cost surcharges (what economists call “externality pricing”); exasperation over the region’s balkanized and convoluted toll and transit regimes; and, of late, a decline in social solidarity and appeals to the common good.

The advent of congestion pricing in New York is, thus, cause not just for celebration but wonderment. How did this wonky yet radical idea advance to the verge of enactment?

Origins

The trail begins in the waning days of 1969, when newly re-elected mayor John Lindsay recruited two well-regarded New Yorkers to devise a plan to fend off a 50 percent rise in subway and bus fares.

William Vickrey, a Canadian transplant teaching at Columbia and a future Nobel economics laureate, was a protean theorist of externality pricing. New York-bred mediator Theodore Kheel was admired as a civic Walter Cronkite for his plain-spoken common sense.

Lindsay, too often dismissed as a lightweight, understood mass transit as key to loosening automobiles’ spreading chokehold over the city. He had made combating air pollution a pillar of his first term and was fast becoming an exemplar of urban environmentalism. From his municipal engineers, Lindsay knew that technology to clean up tailpipes still lay in the future. A transit fare hike that would add yet more vehicles to city streets imperiled his clean-air agenda.

The triumvirate proposed a suite of motorist fees to preserve the fare. Their program ― higher registration fees and gasoline taxes, a parking garage tax, doubled tolls ― though mild in today’s terms, threatened powerful bureaucracies and their auto allies. Newly dethroned “master-builder” Robert Moses opined that Kheel, in his zeal to save the fare, had “gone berserk over bridge and tunnel tolls.”2 The program went nowhere.

L to R: Kheel, Lindsay, Vickrey. Click arrow to view (please excuse two brief garbled passages toward end).

Moses was right to be alarmed. From a City Hall podium on Dec. 16, 1969, Mayor Lindsay showcased Kheel’s and Vickrey’s respective reports, “A Balanced System of Transportation is a Must” and “A Transit Fare Increase is Costly Revenue.” (Click link in still photo above to view 27-minute video.) The trio propounded a new urban doctrine rebalancing automobiles and public transportation: “Automobiles are strangling our cities… Starving mass transit imposes costs that are difficult to measure, yet real… Correcting the fiscal imbalance between transit and the automobile is key to enhancing our environment and quality of life…”

Their remarks set generations of urbanists on course toward congestion pricing.

Setbacks

Quantifying those precepts became my research agenda 40 years later. In the interim, two creditable attempts to enact congestion pricing crashed and burned.

The central element of Lindsay’s 1973 “transportation control plan” was tolls on the city’s East River bridges, a measure designed to eliminate enough traffic to satisfy federal clean-air standards. Though the plan’s formal demise didn’t come until 1977, in legislation written by liberal lawmakers from Brooklyn and Queens, the toll idea never stood a chance. Electronic tolling was 20 years away, and adding stop-and-go toll booths seemed more likely to compound vehicular exhaust than to cut it.

Three decades later, in 2007, Mayor Michael Bloomberg asked Albany to toll not just the same East River bridges but also the more-trafficked 60th Street “portal” to mid-Manhattan. Predictably, faux-populist legislators saw Bloomberg’s billionaire wealth as an invitation to denounce the congestion fee as an affront to the little guy.

The mayor may have hurt his cause by presenting congestion pricing primarily as a climate and pollution measure. The pollution rationale was no longer compelling in the way it had been in Lindsay’s day, as automotive engineers had slashed rates of toxic vehicle exhaust ten-fold. Appeals tied to global warming also fell flat; remember, congestion pricing contemplated that most drivers would stay in their fossil-fuel burning cars.

This isn’t to say that congestion pricing confers no climate benefits. Rather, the benefits are subtler ones that can be hard to convey to voters, such as making climate-friendly urban living more attractive. A further benefit may come as congestion pricing demonstrates the unique power of externality pricing, as explained below.

From the Rubble

Even as Bloomberg’s toll plan was faltering in Albany, new loci of support were germinating in the city.

Changing times demanded not just the intellectual leadership of think-tanks like the Regional Plan Association and the good-government Straphangers Campaign, but gritty, grassroots transit organizing. Enter the newly-minted Riders Alliance.

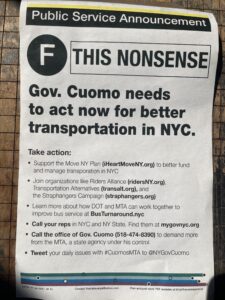

2017 subway handbill exemplified new militancy targeting Gov. Andrew Cuomo for failing transit.

As subway service began cratering in 2015, the inevitable result of budget-raiding by a skein of governors, the Alliance posted crowd-sourced photos of stalled trains and jammed platforms alongside demands for improved service from “#CuomosMTA.” Before long, the papers were pointing the finger at the governor not just in “Why Your Commute Is Bad” explainers but in tear-jerkers like the Times’ May 2017 classic, “Money Out of Your Pocket”: New Yorkers Tell of Subway Delay Woes.

The drumbeat was deafening. Cuomo finally blinked. On a Sunday in August 2017, he phoned the Times’ Albany bureau chief and handed him a scoop for the next day’s front page: Cuomo Calls Manhattan Traffic Plan an Idea ‘Whose Time Has Come’.

The “traffic plan” was congestion pricing.

Data Cruncher

Two months later, Cuomo’s staff summoned me to the midtown office of the consulting firm they had retained to “scope” congestion pricing ― essentially, to compute how much revenue tolls could generate. They wanted to see if an Excel spreadsheet model I had constructed and refined over the prior decade could aid their scoping process.

The model was called the Balanced Transportation Analyzer, a name bestowed in 2007 by Ted Kheel.

Ted, in his nineties, had recruited me to determine whether a large enough congestion toll could pay to make city transit free. The idea worked on paper but foundered politically. Nevertheless, Ted saw in my Excel modeling a way to capture phenomena like “rebound effects” (motorists driving more as road space frees up) and “mode switching” between cars, trains, buses and taxicabs, that he and Prof. Vickrey had identified in their 1969 work but lacked the computing ability to quantify.

Ted’s philanthropy enabled me over the next decade to expand, test and update my transportation modeling. With a hundred “tabs” and 160,000 equations, the “BTA” can instantly answer almost any conceivable question about New York congestion pricing, as well as these two central ones: how much revenue it will yield, and how much time will travelers save in lightened traffic and better transit.3

The BTA model aced its 2017 audition and became the computational engine for the congestion pricing legislation the governor’s team enacted into law in 2019. Its impact has been even broader.4 “Having the model helped make the case with the public, journalists, elected officials and others,” Eric McClure, director of the livable-streets advocacy group StreetsPAC, wrote recently, in part by helping congestion pricing proponents push back on opponents’ exaggerated claims of disastrous outcomes and their incessant demands for special treatment. The model may also have influenced the detailed toll design adopted by the MTA board earlier this year, which hewed close to the toll design I had recommended last summer.5

The BTA also provided sustenance during congestion pricing’s seven lean years ― the 2009-2016 period in which the torch was kept lit by a new triumvirate known as “Move NY” ― traffic guru “Gridlock” Sam Schwartz, the very able campaign strategist Alex Matthiessen, and myself. The model helped our team evangelize congestion pricing’s transformative benefits to elected officials and the public. This, I believe, was a key element in mustering the critical mass of support that ultimately swayed not one but two governors.

The Hochul Factor

New York Lieutenant Governor Kathy Hochul’s ascension to governor in August 2021 could have been congestion pricing’s death knell. The toll plan was adrift in the federal bureaucracy, and its latter-day champion Andrew Cuomo had exited in “me-too” disgrace. His successor, from distant Buffalo, wasn’t beholden to New York or congestion pricing.

Hochul, who as governor controls city and regional transit, could have disowned congestion pricing as convoluted, bureaucratic and tainted. Instead, she became a resolute and enthusiastic backer. Her spirited support, both in public and behind the scenes, became the decisive ingredient in shepherding congestion pricing to safety.

Why the new governor went all-in on congestion pricing awaits a future journalist or historian. Had she spurned it, the opprobrium from downstate transit advocates would have been intense; but there doubtless would have been cries of “good riddance” as well. Vickrey, Kheel and Riders Alliance notwithstanding, it’s not clear how closely New Yorkers — including transit users — connect congestion tolls to improved travel and a better city.

What makes Hochul’s embrace especially impressive is that congestion pricing is, in a real sense, an attack on a jealously guarded entitlement: the right to inconvenience others by usurping public space for one’s vehicle. The classic lament about entitlements’ iron grip is that “losers cry louder than winners sing.”6 Yet in this case, it seems, potential losers — actual and aspiring zone-bound drivers — are being out-sung by transit interests seeking, in Kheel’s 1969 words, a better balance between public transportation and automobiles.

Credits and Prospects

Let us now praise Andrew Cuomo’s crafting of the legislation that teed up congestion pricing’s successful run.

Rather than specifying a dollar price for the tolls, or a precise traffic reduction, his 2019 bill established a revenue target: sufficient earnings to bond $15 billion in transit investment — which equates to $1 billion a year to cover debt service. This device trained the public’s focus on the gain from congestion pricing (better transit) instead of the pain (the toll). Equally important, with this deft stroke, any toll exemption that a vocal minority might seek would mathematically trigger higher tolls for everyone else. The effect was vastly heightened scrutiny of requests for carve-outs.

Which cities will follow on New York’s heels? No U.S. urban area comes close to our trifecta of gridlock, transit and wealth. Sprawling Los Angeles or Houston, or even Chicago for that matter, might be better served by more granulated traffic tolls than New York’s all-or-none model.

Perhaps Asia’s megalopolises will be swept up in our wake. In the meantime, my focus will be on the holy grail of externality pricing: taxing carbon emissions. Every economist knows that the surest and fastest way to cut down on a “bad” is by taxing it rather than subsidizing possible alternatives. Yet that approach remains counter-intuitive and even anathema to nearly everyone else.

A huge and important legacy that New York congestion pricing could provide is to prove that intelligently taxing societal harms need not be electoral suicide. This proof could help unlock a treasure-trove of prosperity-enhancing pricing reforms including, most prominently, robust carbon taxing.

The author, a policy analyst based in New York City, worked in Mayor Lindsay’s Environmental Protection Administration in 1972-1974. He met Bill Vickrey in 1991 and worked closely with Ted Kheel from 2007 to 2010.

Endnotes

- The new passenger surcharges of $1.25 for taxicabs and $2.50 for “ride-hails” (principally Ubers) apply to trips touching the congestion zone. These will be partially offset by lower fares owing to shorter wait-time charges due to faster travel speeds.

- Quote is from Moses’ August 23, 1969 guest essay in Newsday, “Is Rubber to Pay for Rails?” (not digitally available).

- The current version of the BTA is publicly available at this link: (18 MB Excel file).

- See Fix NYC Advisory Panel Report, Appendix B, 2019.

- A Congestion Toll New York Can Live With, July 2023, by Charles Komanoff, co-authored with Columbia Business School economist Gernot Wagner.

- As pronounced by University of Michigan economist Joel Slemrod, in Goodbye, My Sweet Deduction, New York Times, by Eduardo Porter and David Leonhardt, Nov. 3, 2005.

A Tantalizing New Front in Externality Pricing: Taxing Helicopter Noise

The New York City Council today held a hearing on a suite of bills to limit noise from helicopter flights over New York City. The bill most pertinent to carbon taxing is a resolution supporting a proposed NY State $400 “noise tax” on flights taking off or landing at the city’s heliports.

My testimony, presented below, situates the proposed noise tax in the context of social-damage costing, also known as externality pricing. Previous CTC posts in this vein have covered NYC’s forthcoming congestion pricing plan, a California growers’ program that taxes excess withdrawals of groundwater for farming, and Berkeley, CA’s soda tax.

Educator from the NYC harbor ecology group Billion Oyster Project, at the April 16 City Hall Park rally organized by Stop The Chop NY/NJ. To speaker’s left are Councilmembers Lincoln Restler and Amanda Farias, lead sponsors of Intro 70 and Intro 26. Author photo.

As can be seen from photographs of the rally prior to the council hearing, the anti-heli-noise outfit Stop The Chop NY/NJ takes a reformist position on helicopter flights. I’m more militant in both deed, having helped organize a human blockade of the West 30th Street (Hudson River) heliport last September and language, preferring the term “luxury fights” to Stop The Chop’s “nonessential flights.”

That said, I tip my hat to Stop The Chop for their scrappy advocacy that has raised the profile of helicopters’ aural and other assaults on New Yorkers’ quality of life. The bills in question would not have been written and advanced without their years of organizing.

Testimony of Charles Komanoff[1] supporting Council Bills banning nonessential helicopter flights using municipal properties, and Council Resolution 0085-2024 endorsing state legislation imposing a noise-annoyance surcharge on nonessential helicopter flights in New York City[2]. Submitted on April 16, 2024. (My statement has been lightly edited for clarity. Bracketed numbers denote endnotes.)

I emphatically support Council bills Intro 26 and Intro 70 banning nonessential helicopter flights from the two City-run heliports. In addition, as an economist specializing in environmental costing,[3] I’d like to single out for praise Council Resolution 0085-2024 endorsing state legislators Kirsten Gonzalez’s and Bobby Carroll’s bills S7216B and A7638B imposing a noise fee on nonessential helicopter flights.[4]

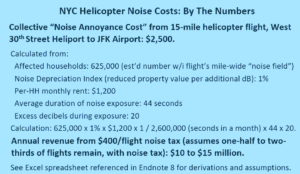

The Gonzalez-Carroll noise fee is $100 per occupied seat or $400 per flight, whichever amount is larger. Although these levies are less than the average helicopter flight’s apparent societal cost, they are a commendable starting point. The levies can be raised later on, as methodologies for quantifying helicopter noise costs mature — a process that will be aided by passing a related bill in the Council, Intro 27. The fees can also be lowered if quieter helicopters emerge — which the Gonzalez-Carroll bills will incentivize.

“Cost internalization,” as this kind of social-damage pricing is termed, is long overdue for helicopter noise. The luxury helicopter flights targeted by the Gonzalez and Carroll bills are completely discretionary. Anyone taking such a flight — whether to the Hamptons or JFK or for sightseeing — has money to spare, as revealed by their pricey transportation choice. Taxing helicopter noise is entirely consistent with economic justice. Moreover, these flights impose other costs beyond noise, such as carbon pollution and particulate-exhaust pollution, on everyone around or below.

Consider Blade’s JFK helicopter service from its Manhattan West 30th Street heliport — a flight covering about 15 miles. I’ve made a preliminary but serviceable calculation suggesting that one such flight lasting just seven minutes steals around $2,500 worth of peace and quiet from city residents.[5]

A more militant protest: Extinction Rebellion’s Sept 2023 human heliport blockade. See our post from that month, “Grounding Helicopter Luxury.” Photo: Christopher Ketcham.

The Gonzalez-Carroll noise fee amounts to a roughly 40 percent surcharge to Blade’s $250 standard ticket price to JFK, making it a worthy start. Assemblymember Carroll has been a legislative leader on externalities taxing, and it’s great to see Sen. Gonzalez also taking up the cause.

A noise fee raising the price of a commuter helicopter trip by 40 percent will cut usage, hence, the number of flights, by 30 to 50 percent,[6] as some would-be passengers opt out. (Yes, just like congestion pricing, except more draconian, and deservedly so, given luxury helicopters’ societal uselessness). That will not only bring a healthy measure of peace and quiet, it will generate $10 to $15 million per year[7] — revenue that New York City can use to expand and enforce noise-abatement rules citywide.

Noise isn’t the sole harm that commuter and tourist helicopters inflict on the millions of residents below. But it is the most egregious and insulting. Every member should vote Yes on the bills to ban nonessential helicopter flights from the two City-owned heliports. And please also vote for Council Resolution 0085-2024 to make clear to your Albany counterparts that New York City’s local elected officials support the Gonzalez-Carroll helicopter noise fee.

Endnotes.[8]

[1] Policy analyst and consulting economist at KEA, 11 Hanover Square, 21st floor, New York, NY 10005. Website www.komanoff.net.

[2] This document is available on line as https://www.komanoff.net/jet_skis/Komanoff_Testimony_City_Council_Helicopter_Noise_Costs.pdf.

[3] My work quantifying and supporting NYC congestion pricing is widely known; much of it is collected here. My body of research also includes Drowning in Noise: Noise Costs of Jet Skis in the United States, a monograph co-authored with Dr. Howard Shaw and published in 2000 by the Noise Pollution Clearinghouse.

[4] Assemblymember Bobby Carroll represents part of Brooklyn. State Senator Kristen Gonzalez represents parts of Brooklyn, Queens and Manhattan.

[5] Key assumptions in my calculation of a $2,500 collective noise cost per flight from W 30 St to JFK Blade include: 625,000 households in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens households lie within the helicopter noise field; excess noise of 20 dBA during the average 44 seconds of noise exposure for each flight; a “Noise Depreciation Index” — reduced property value per additional decibel during exposure — of 1%. Some parameters in the calculation are placeholder values, making the resulting $2,500 estimated per-flight collective noise cost preliminary and subject to change. See Excel spreadsheet referenced in final endnote.

[5] Key assumptions in my calculation of a $2,500 collective noise cost per flight from W 30 St to JFK Blade include: 625,000 households in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens households lie within the helicopter noise field; excess noise of 20 dBA during the average 44 seconds of noise exposure for each flight; a “Noise Depreciation Index” — reduced property value per additional decibel during exposure — of 1%. Some parameters in the calculation are placeholder values, making the resulting $2,500 estimated per-flight collective noise cost preliminary and subject to change. See Excel spreadsheet referenced in final endnote.

[6] The 30 percent reduction is associated with a price-elasticity of helicopter flights of negative 1, while the 50 percent reduction comes from a price-elasticity of negative 2. The respective calculations are: 1.4^(-1) ~ 0.7, and 1.4^(-2) ~ 0.5. (My high price-elasticity figures reflect the discretionary and luxury nature of helicopter travel.) See Excel spreadsheet referenced in final endnote.

[7] The number of helicopter flights per year that would be subject to the Gonzalez-Carroll noise tax appears to be between 50,000 and 60,000 per year. I have used the lower figure (50,000) in my calculations. Taking into account that the incorporation of the proposed tax into the price of helicopter flights would be expected to reduce the number of flights by 30 to 50 percent, and applying a per-flight noise fee of $400, the annual tax revenues, rounded, calculate to between $10 and $15 million per year (50k x $400 x 50% or 70%).

[8] An Excel spreadsheet (NYC_Helicopter_Flights_Externality_Costs.xls) with assumptions, calculations and citations supporting my preliminary $2,500 per-flight noise cost estimate, my tax revenue estimate of $10 to $15 million, and other figures in my testimony may be downloaded via this link: https://www.komanoff.net/jet_skis/NYC_Helicopter_Flights_Externality_Costs.xlsx.

The 2 Big Things Missing from Coverage of Nuke Plant Shutdowns

Next month will mark four years since the Indian Point nuclear power plant north of New York City began to be shut down.

Indian Point 2 was closed on April 30, 2020. Indian Point 3’s closure followed a year later. The two units, rated at roughly 1,000 megawatts each, started operating in the mid-1970s. A half-century later, their reactor cores lie dismembered. Both units are irretrievably gone, for better or worse.

I believe the closures are for the worse — and not by a little. The loss of Indian Point’s 2,000 MW of virtually carbon-free power has set back New York’s decarbonization efforts by at least a decade. And that’s almost certainly an understatement.

I hinted at this in Drones With Hacksaws: Climate Consequences of Shutting Indian Point Can’t Be Brushed Aside, a May 2020 post in the NY-area outlet Gotham Gazette. Over time I grew more outspoken. In two posts for The Nation in April 2022 (here and here) I invoked Indian Point to urge Californians to revoke a parallel plan to close Pacific Gas & Electric’s two-unit Diablo Canyon nuclear plant, which I followed up with a plea to Gov. Gavin Newsom to scuttle the shutdown deal, co-signed by clean-air advocate Armond Cohen and whole-earth avatar Stewart Brand. Which the governor did, last year.

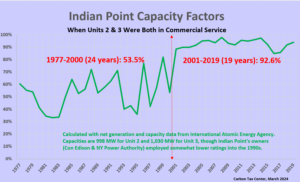

Once I had regarded nuclear plant closures as no big deal. Now I was telling all who would listen that junking high-performing thousand-megawatt reactors on either coast was a monstrous climate crime, the carbon equivalent to decapitating many hundreds of giant wind turbines — a metaphor I employed in my Gotham Gazette post. My turnaround rested on two clear but overlooked points.

One was that nearly all extant U.S. nukes had long ago morphed from chronic inconsistency into rock-solid generators of massive volumes of carbon-free kilowatt-hours, with “capacity factors” reliably hitting 90% or even higher. This positive change should have put to rest the antinuclear movement’s shopworn “aging and unsafe” narrative about our 90-odd operating reactors. It also elevated the plants’ economic and climate value, making politically forced closures far more costly than most of us had imagined.

The other new point is connected to carbon and climate: The effort to have “renewables” (wind, solar and occasionally hydro) fill the hole left from closing Indian Point or other nuclear plants isn’t just tendentious and difficult. Rather, the very construct that one set of zero-carbon generators (renewables) can “replace” another (nuclear) with no climate cost is simplistic if not downright false, as I explain further below.

These new ideas came to mind as I read a major story this week on the consequences of Indian Point’s closure in The Guardian by Oliver Milman, the paper’s longtime chief environment correspondent. To his credit, Milman delved pretty deeply into the impacts of reactor closures — more so than any prominent journalist has done to date. Nonetheless, it’s time for coverage of nuclear closures to go further. To assist, I’ve posted Milman’s story verbatim, with my responses alongside.

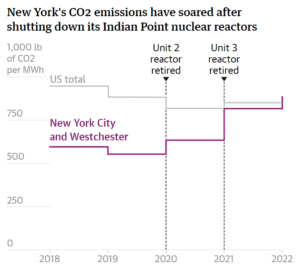

A nuclear plant’s closure was hailed as a green win. Then emissions went up.By Oliver Milman, The Guardian, March 20, 2024 When New York’s deteriorating and unloved Indian Point nuclear plant finally shuttered in 2021, its demise was met with delight from environmentalists who had long demanded it be scrapped. But there has been a sting in the tail – since the closure, New York’s greenhouse gas emissions have gone up. Castigated for its impact upon the surrounding environment and feared for its potential to unleash disaster close to the heart of New York City, Indian Point nevertheless supplied a large chunk of the state’s carbon-free electricity.  Guardian graphic using eGRID data for NYCW subregion. The chart’s other half was excised to fit the available space. Since the plant’s closure, it has been gas, rather then clean energy such as solar and wind, that has filled the void, leaving New York City in the embarrassing situation of seeing its planet-heating emissions jump in recent years to the point its power grid is now dirtier than Texas’s, as well as the US average. “From a climate change point of view it’s been a real step backwards and made it harder for New York City to decarbonize its electricity supply than it could’ve been,” said Ben Furnas, a climate and energy policy expert at Cornell University. “This has been a cautionary tale that has left New York in a really challenging spot.” The closure of Indian Point raises sticky questions for the green movement and states such as New York that are looking to slash carbon pollution. Should long-held concerns about nuclear be shelved due to the overriding challenge of the climate crisis? If so, what should be done about the US’s fleet of ageing nuclear plants? For those who spent decades fighting Indian Point, the power plant had few redeeming qualities even in an era of escalating global heating. Perched on the banks of the Hudson River about 25 miles north of Manhattan, the hulking facility started operation in the 1960s and its three reactors at one point contributed about a quarter of New York City’s power. (Guardian/Milman continued) It faced a constant barrage of criticism over safety concerns, however, particularly around the leaking of radioactive material into groundwater and for harm caused to fish when the river’s water was used for cooling. Pressure from Andrew Cuomo, New York’s then governor, and Bernie Sanders – the senator called Indian Point a “catastrophe waiting to happen” – led to a phased closure announced in 2017, with the two remaining reactors shutting in 2020 and 2021. The closure was cause for jubilation in green circles, with Mark Ruffalo, the actor and environmentalist, calling the plant’s end “a BIG deal”. He added in a video: “Let’s get beyond Indian Point.” New York has two other nuclear stations, which have also faced opposition, that have licenses set to expire this decade. But rather than immediately usher in a new dawn of clean energy, Indian Point’s departure spurred a jump in planet-heating emissions. New York upped its consumption of readily available gas to make up its shortfall in 2020 and again in 2021, as nuclear dropped to just a fifth of the state’s electricity generation, down from about a third before Indian Point’s closure. This reversal will not itself wreck New York’s goal of making its grid emissions-free by 2040. Two major projects bringing Canadian hydropower and upstate solar and wind electricity will come online by 2027, while the state is pushing ahead with new offshore wind projects – New York’s first offshore turbines started whirring last week. Kathy Hochul, New York’s governor, has vowed the state will “build a cleaner, greener future for all New Yorkers.” Even as renewable energy blossoms at a gathering pace in the US, though, it is gas that remains the most common fallback for utilities once they take nuclear offline, according to Furnas. This mirrors a situation faced by Germany after it looked to move away from nuclear in the wake of the Fukushima disaster in 2011, only to fall back on coal, the dirtiest of all fossil fuels, as a temporary replacement. “As renewables are being built we still need energy for when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining and most often it’s gas that is doing that,” said Furnas. “It’s a harrowing dynamic. Taking away a big slice of clean energy coming from nuclear can be a self-inflicted wound from a climate change point of view.” With the world barreling towards disastrous climate change impacts due to the dawdling pace of emissions cuts, some environmentalists have set aside reservations and accepted nuclear as an expedient power source. The US currently derives about a fifth of its electricity from nuclear power. Bill McKibben, author, activist and founder of 350.org, said that the position “of the people I know and trust” is that “if you have an existing nuke, keep it open if you can. I think most people are agnostic on new nuclear, hoping that the next generation of reactors might pan out but fearing that they’ll be too expensive. “The hard part for nuclear, aside from all the traditional and still applicable safety caveats, is that sun and wind and batteries just keep getting cheaper and cheaper, which means the nuclear industry increasingly depends on political gamesmanship to get public funding,” McKibben added. (Guardian/Milman continued) Wariness over nuclear has long been a central tenet of the environmental movement, though, and opponents point to concerns over nuclear waste, localized pollution and the chance, albeit unlikely, of a major disaster. In California, a coalition of green groups recently filed a lawsuit to try to force the closure of the Diablo Canyon facility, which provides about 8% of the state’s electricity.

Templeton said the groups were alarmed over Diablo Canyon’s discharge of waste water into the environment and the possibility an earthquake could trigger a disastrous leak of nuclear waste. A previous Friends of the Earth deal with the plant’s operator, PG&E, to shutter Diablo Canyon was clouded by state legislation allowing the facility to remain open for another five years, and potentially longer, which Templeton said was a “twist of the knife” to opponents. “We are not stuck in the past – we are embracing renewable energy technology like solar and wind,” she said. “There was ample notice for everyone to get their houses in order and switch over to solar and wind and they didn’t do anything. The main beneficiary of all this is the corporation making money out of this plant remaining active for longer.” Meanwhile, supporters of nuclear – some online fans have been called “nuclear bros” – claim the energy source has moved past the specter of Chernobyl and into a new era of small modular nuclear reactors. Amazon recently purchased a nuclear-powered data center, while Bill Gates has also plowed investment into the technology. Rising electricity bills, as well as the climate crisis, are causing people to reassess nuclear, advocates say. “Things have changed drastically – five years ago I would get a very hostile response when talking about nuclear, now people are just so much more open about it,” said Grace Stanke, a nuclear fuels engineer and former Miss America who regularly gives talks on the benefits of nuclear. “I find that young people really want to have a discussion about nuclear because of climate change, but people of all ages want reliable, accessible energy,” she said. “Nuclear can provide that.” |

The forces that won Indian Point’s closure were blind to the climate cost.By Charles Komanoff, Carbon Tax Center, March 23, 2024 New Reality #1: Indian Point wasn’t “deteriorating” when it was closed.“Deteriorating and unloved” is how Milman characterized Indian Point in his lede. “Unloved?” Sure, though probably no U.S. generating station has been fondly embraced since Woody Guthrie rhapsodized about the Grand Coulee Dam in the 1940s. But “deteriorating”? How could a power plant on the verge of collapse run for two decades at greater than 90% of its maximum capacity?  Calculations by author from International Atomic Energy Agency data. Diablo Canyon has also averaged over 90% CF since 2000. Had Indian Point been less productive, the jump in the metropolitan area’s carbon emission rate would have been far less than the apparent 60 percent increase in the Guardian graph at left. Though the “electrify everything” community is loath to discuss it, the emissions surge from closing Indian Point significantly diminishes the purported climate benefit from shifting vehicles, heating, cooking and industry from combustion to electricity . The impetus for shutting Indian Point largely came through, not from then-Gov. Cuomo.Milman pins the decision to close Indian Point on NY Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Vermont’s U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders. While Cuomo backed and brokered the deal (which Sanders had nothing to do with), the real push came from a coalition of NY-area environmental activists led by Riverkeeper, who, as he notes, “spent decades fighting Indian Point.” And it was relentless. The wellsprings of their fight were many, from Cold War fears of anything nuclear to a fierce devotion to the Hudson River ecosystem, which Indian Point threatened not through occasional minor radioactive leaks but via larval striped bass entrainment on the plant’s intake screens. Their fight was of course supercharged by the 1979 Three Mile Island reactor meltdown in Pennsylvania and, later, by the 9/11 hijackers’ Hudson River flight path. But as I pointed out in Gotham Gazette, few shutdown proponents had carbon reduction in their organizational DNA. None had ever built anything, leaving many with a fantasyland conception of the work required to substitute green capacity for Indian Point. (CTC/Komanoff continued) And while the shutdown forces proclaimed their love for wind and solar, their understanding of electric grids and nukes was stuck in the past. To them, Indian Point was Three Mile Island (or Chernobyl) on the Hudson — never mind that by the mid-2010s U.S. nuclear power plants had multiplied their pre-TMI operating experience twenty-fold with nary a mishap. No, in most anti-nukers’ minds, Indian Point would forever be a bumbling menace incapable of rising above its previous-century average 50% capacity factor (see graph above). Most either ignored the plant’s born-again 90% online mark or viewed it as proof of lax oversight by a co-opted Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Note too that the “hulking facility,” as Milman termed Indian Point, lay a very considerable 35 air miles from Columbus Circle, rather than “25 miles north of Manhattan,” a figure that references the borough’s uninhabited northern tip. NYC residents had more immediate concerns, leaving fear and loathing over the nukes to be concentrated among the plant’s Westchester neighbors (Cuomo’s backyard). Which raises the question of why in-city environmental justice groups failed to question the shutdown, which is now impeding closure of polluting “peaker” plants in their own Brooklyn, Queens and Bronx backyards. Still, the shutdown campaigners’ most grievous lapse was their failure to grasp that the new climate imperative requires a radically different conceptual framework for gauging nuclear power. New Reality #2: Wind and solar that are replacing Indian Point can’t also reduce fossil fuels.It’s dispiriting to contemplate the effort required to create enough new carbon-free electricity to generate Indian Point’s lost carbon-free output. Think 500 giant offshore wind turbines, each rated at 8 megawatts. (Wind farms need twice the capacity of Indian Point, i.e., 4,000 MW vs. 2,000, to offset their lesser capacity factor.) What about solar PV? Its capacity disadvantage vis-a-vis Indian Point’s 90% is five- or even six-fold, meaning 10,000 or more megawatts of new solar to replace Indian Point. I won’t even try to calculate how many solar buildings that would require. But this is where Indian Point’s 90% capacity factor is so daunting; had the plant stayed mired at 60%, the capacity ratios to replace it would be a third less steep. But wait . . . it’s even worse. These massive infusions of wind or solar are supposed to be reducing fossil fuel use by helping the grid phase out gas (methane) fired electricity. Which they cannot do, if they first need to stand in for the carbon-free generation that Indian Point was providing before it was shut. So when Riverkeeper pledged in 2015-2017, or Friends of the Earth’s legal director told the Guardian‘s Milman that “we are embracing renewable energy technology like solar and wind,” they’re misrepresenting renewables’ capacity to help nuclear-depleted grids cut down on carbon. Shutting a functioning nuclear power plant puts the grid into a deep carbon-reduction hole — one that new solar and wind must first fill, at great expense, before further barrages of turbines and panels can actually be said to be keeping fossil fuels in the ground. (CTC/Komanoff continued) I suspect that not one in a hundred shut-nukes-now campaigners grasps this frame of reference. I certainly didn’t, until one day in April 2020, mere weeks before Indian Point 2 would be turned off, when an activist with Nuclear NY phoned me out of the blue and hurled this new paradigm at me. Before then, I was stuck in the “grid sufficiency” framework that was limited to having enough megawatts to keep everyone’s A/C’s running on peak summer days. The idea that the next giant batch or two of renewables will only keep CO2 emissions running in place rather than reduce them was new and startling. And irrefutably true. To be clear, I don’t criticize Milman for missing this new paradigm. He’s a journalist, not an analyst or activist. It’s on us climate advocates to propagate it till it reaches reportorial critical mass. I credit Milman for giving FoE’s legal director free rein about Diablo. “There was ample notice for everyone to get their houses in order and switch over to solar and wind and they didn’t do anything,” she told him. Goodness. Everyone [who? California government? PG&E? green entrepreneurs?] didn’t do anything to switch over to solar and wind. Welcome to reality, Friends of the Earth! I knew FoE’s legendary founder David Brower personally. I and legions of others were inspired in the 1960s and 1970s by his implacable refusal to accede to the world as it was and his monumental determination to build a better one. But reality has its own implacability. The difficulty of bringing actual wind and solar projects (and more energy-efficiency) to fruition has the sad corollary that shutting viable nuclear plants consigns long-sought big blocks of renewables to being mere restorers of the untenable climate status quo. In closing: Contrary to Milman (and NY Gov. Kathy Hochul), Indian Point’s closure will wreck NY’s goal of an emissions-free grid by 2040.“Two major projects bringing Canadian hydropower and upstate solar and wind electricity will come online by 2027,” Milman wrote, referencing the Champlain-Hudson Power Express transmission line and Clean Path NY. But their combined annual output will only match Indian Point’s lost carbon-free production. Considering that loss, the two ventures can’t be credited with actually pushing fossil fuels out of the grid. That will require massive new clean power ventures, few of which are on the horizon. I’ve written about the travails of getting big, difference-making offshore wind farms up and running in New York. I’ve argued that robust carbon pricing could help neutralize the inflationary pressures, supply bottlenecks, higher interest rates and pervasive NIMBY-ism that have led some wind developers to deep-six big projects. Though I’ve yet to fully “do the math,” my decades adjacent to the electricity industry (1970-1995) and indeed my long career in policy analysis tell me that New York’s grid won’t even reach 80% carbon-free by 2040 unless the state or, better, Washington legislates a palpable carbon price that incentivizes large-scale demand reductions along with faster uptake of new wind, solar and, perhaps, nuclear. |

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- 18

- Next Page »

“Diablo Canyon has not received the safety upgrades and maintenance it needs and we are dubious that nuclear is safe in any regard, let alone without these upgrades – it’s a huge problem,” said Hallie Templeton, legal director of Friends of the Earth, which was founded in 1969 to, among other things, oppose Diablo Canyon.

“Diablo Canyon has not received the safety upgrades and maintenance it needs and we are dubious that nuclear is safe in any regard, let alone without these upgrades – it’s a huge problem,” said Hallie Templeton, legal director of Friends of the Earth, which was founded in 1969 to, among other things, oppose Diablo Canyon.