Pembina Institute Calls for Fairer, Higher British Columbia Carbon Tax (The Hook, A Tyee Blog, British Columbia)

Search Results for: british columbia

In British Columbia, a carbon tax wins popular support

In British Columbia, a carbon tax wins popular support (Canada Global Post)

British Columbia Premier Says NDP Plan to 'Axe the Tax' is Playing Politics

British Columbia Premier Says NDP Plan to ‘Axe the Tax’ is Playing Politics (CBCNews.ca)

Carbon Tax Guarantees Tax Cuts for British Columbians

The British Columbia Ministry of Finance issued this News Release on April 28. It speaks for itself and requires no comment from the Carbon Tax Center.

N E W S R E L E A S E

For Immediate Release Ministry of Finance

2008FIN0009-000615

April 28, 2008

CARBON TAX GUARANTEES TAX CUTS FOR BRITISH COLUMBIANS

VICTORIA — British Columbia is the first province to implement a comprehensive, revenue-neutral carbon tax – an initiative that returns every dollar raised to the people and businesses of British Columbia as tax cuts, Finance Minister Carole Taylor announced today.

“British Columbia is leading the way in addressing climate change, and the revenue-neutral carbon tax is another pioneering step forward for our province,” said Taylor. “Each step we take to change our habits and behaviours, as individuals and as a community, will help leave a legacy that our children and grandchildren can be proud of.”

By tying the carbon tax to reductions in personal and business taxes, the Province is giving the people of British Columbia the power to make their own choices.

“Pricing carbon sends a clear message that there is a cost to the environment involved in emitting carbon,” said Taylor. “Leading economists and scientists agree that introducing a revenue-neutral carbon tax is the right thing for our province, today and for the future. We took time to design a model that protects low-income families and moves British Columbia to being one of the lowest-taxing provinces in Canada.”

In the first three years, the carbon tax is estimated to generate $1,849 million in revenue, which will be returned to British Columbians as follows:

The bottom two personal income tax rates will be reduced for all British Columbians, resulting in a tax cut of two per cent in 2008, rising to five per cent in 2009 on the first $70,000 in earnings – with further reductions expected in 2010: $784 million.

Effective July 1, 2008, the general corporate income tax rate will be reduced to 11 per cent from 12 per cent – with further reductions planned to 10 per cent by 2011: $415 million.

Effective July 1, 2008, the small business tax rate will be reduced to 3.5 per cent from 4.5 per cent – with further reductions planned to 2.5 per cent by 2011): $255 million.

Beginning July 1, 2008, the new Climate Action Credit will provide lower-income British Columbians a payment of $100 per adult and $30 per child per year – increasing by five per cent in 2009 and possibly more in future years: $395 million.

Total tax cuts over three years:$1,849 million.

This groundbreaking legislation is supplemented by an immediate Climate Action Dividend, $100 for every man, woman and child in British Columbia. This dividend, which will further support our community’s ability to make greener choices, will go out to residents of British Columbia starting in late June.

For further information about the carbon tax and ideas for making greener choices, please visit:

http://www.bcbudget.gov.bc.ca/2008/backgrounders/backgrounder_tax_impacts.htm

Media Contact

Finance Communications

Public Affairs Bureau

250 387-5013

For more information on government services or to subscribe to the Province’s news feeds using RSS, visit the Province’s website at www.gov.bc.ca.

Behind British Columbia's Carbon Tax

We reported last week that British Columbia will implement a carbon tax of $10 per metric ton of carbon on July 1, rising in $5/tonne annual increments to reach $30 in 2012.

In both scope and size, the tax leapfrogs North America’s other, modest carbon taxes, in Quebec and the City of Boulder, Colorado. How did the tax come about? CTC supporter Jurgen Hissen filed this account from Vancouver.

The idea for a carbon tax came from the top ranks of the BC government. It wasn’t foisted upon them. I think they were actively seeking ways to justify it to the citizenry.

BC Liberals — who aren’t connected to Canada’s national Liberal Party — have always been pro small-government. When they came into office in 2001, they cut taxes and government spending extensively. BC Liberals have also historically emphasized personal responsibility and environmental issues, and a carbon tax (a consumption tax) is pretty consistent with that.

After meeting last year with California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, BC Premier Gordon Campbell resolved to set carbon reduction targets for BC. Suggestions of a carbon tax began circulating, but the real push likely came from Carole Taylor, Campbell’s finance minister.

In late 2007, Taylor assembled a committee, the Select Standing Committee on Finance and Government Services, to collect public input on the budget. The committee issued a questionnaire to every household in the province; how to tackle climate change covered three of the six questions, and two of them were what pollsters would call “leading”:

The Province currently provides tax incentives to encourage the purchase of hybrid vehicles [… etc.]. What tax changes would you make to encourage environmentally responsible choices? and

What tax changes would you make to discourage British Columbians from activities that contribute to greenhouse gas emissions?

Clearly, the government was looking to rationalize carbon taxes. The response was favorable, and crucial, not to mention broad-based. A carbon tax was backed by business leaders, a group of 60 economists from BC universities, and key religious leaders.

Taylor, the finance minister, reported getting 700 letters in support of a carbon tax (about 10 of those were mine, I think), and only about 160 opposed — a fact she cited on the day she announced the tax.

CTC invites readers from British Columbia or elsewhere to write with further details/insights on the development of BC’s carbon tax as well as potential implications for other provinces and the U.S.

Photo: Wikipedia

British Columbia Introduces Revenue-Neutral Carbon Tax

British Columbia’s Finance Minister Carole Taylor introduced a revenue-neutral carbon tax today that will serve as an excellent model for the United States. According to a story in the Canadian Press, the carbon tax will be effective July 1, will be phased in over five years and will start at a rate of $10 per tonne of carbon emissions. It will rise $5 a year to $30 per ton by 2012. The carbon tax revenues will be returned to taxpayers through personal income and business income tax cuts, according to Taylor.

According to the same story, climate specialist Ian Bruce of the David Suzuki Foundation stated that "The Government has used the most powerful tool, a carbon tax, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions." As Bruce pointed out, "Green choices will become cheaper."

According to the same story, climate specialist Ian Bruce of the David Suzuki Foundation stated that "The Government has used the most powerful tool, a carbon tax, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions." As Bruce pointed out, "Green choices will become cheaper."

B.C. can now be proud of its natural beauty and its wise public policy designed to reduce the impact of climate change. Note that the proposed new carbon tax is very similar to the revenue-neutral, phased-in carbon tax proposed by the Carbon Tax Center.

For more on the new B.C. carbon tax, see stories at right under "Latest Headlines."

Photo: bfraz / flickr

Congestion pricing, coming soon to New York City, could bode well for carbon-taxing.

Externality pricing is coming to New York City in a big, barrier-busting form known as congestion pricing. Judging from how it’s unfolding, it might just be bold enough to give a much-needed boost to the cause of U.S. carbon pricing.

In a long-awaited step, New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority this week unveiled its prospective tolls to drive a car or truck into Manhattan’s central business district. Barring a last-minute reversal, the Western hemisphere’s first congestion pricing program, and the world’s biggest by far in terms of revenue, will begin next June, just six months from now.

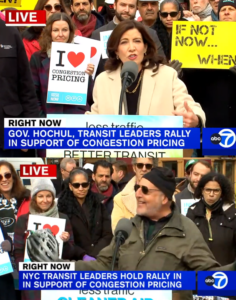

NY Gov. Kathy Hochul (top) and CTC director Charles Komanoff (below) speaking at Dec. 5 Union Square rally celebrating the march toward congestion pricing in NYC.

The plan took half-a-century to legislate and another four-and-a-half years to flesh out, culminating, for now, in its formal approval by the MTA board on Wednesday. Autos will be charged $15 to drive into Manhattan south of 60th Street between 5am-9pm weekdays and 9am-9pm weekends and holidays. Night-time tolls will be 75 percent lower, at $3.75. Trucks will pay more than cars, and for-hire vehicle trips that touch any part of the 8-square-mile congestion zone will be surcharged $1.25 (for yellow cabs) and $2.50 (for “ride-hail” vehicles, largely Ubers). Peak-period car trips to the zone via tunnels under the Hudson and East Rivers, which already pay double-digit round-trip tolls, will get $5 off, but other exemptions or discounts will be few except for low-income residents of the zone and commuters to it. (Many details here, by the author; and here, by the MTA’s toll-setting panel.)

The 2019 state legislation authorizing the tolls requires that they generate $1 billion a year net of administrative costs — a revenue stream sufficient to bond $15 billion in transit investments. Eighty percent of that, $12 billion, is earmarked for subway improvements such as station elevators to increase accessibility and fully digital signals to allow more frequent train service; the other $3 billion will be invested in expanding commuter rail service between the suburbs and Manhattan.

[Click here to watch/hear Gov. Hochul’s remarks depicted above. Click here for Komanoff’s.]

Revenue Most Visible

The billion-dollar a year take from New York congestion pricing puts it in the same league as the Northeast states’ Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, which currently reaps $1.2 billion a year from sales of carbon emission permits for burning fossil fuels to make electricity. Yet “RGGI” is largely invisible to the public. So too are California’s economy-wide carbon cap-and-trade program, which started in 2013, and British Columbia’s 2008 carbon tax as well as subsequent cap-and-trade schemes elsewhere in Canada, .

Those other mechanisms rest on what former CTC staffer James Handley habitually derided as “hide the price” subterfuges. Congestion pricing, in contrast, hides nothing. Motorists know full well what they’ll soon have to pay to drive into the nation’s most gridlocked (and transit-rich) district. True, the surcharges on for-vehicle trips can be tricky to track — they add to rather than replace incumbent FHV surcharges of $2.50 and $2.75 for “taxi zone” trips in yellows and ride-hails, respectively. But congestion pricing’s main event is the fees for private car trips.

And “main event” is putting it mildly. Though the $15 peak car toll is many times less than the socially optimal toll (per Paul Krugman, whose July encomium to congestion program relied indirectly on my traffic-cost modeling) or the congestion costs imposed by a single car trip, which is nearly the same thing, it’s still a gut-punch for diehard drivers. Not only that, imposing a hefty price on car travel to capture externality costs rather than merely to pay for infrastructure provision is, let us say, deliciously transgressive in the USA. Kind of like taxing carbon emissions.

The point being: successfully implementing congestion pricing in New York — not simply putting it in place but having it deliver tangible benefits like more-reliable travel, more-livable streets and re-invigorated public transportation — conceivably could burnish carbon pricing not just in New York but nationwide.

Enacting Carbon Taxes Remains Devilishly Difficult

Let’s be clear, though. As if getting New York congestion pricing within inches of the goal line hasn’t been hard enough, enacting a national, i.e., federal carbon tax worthy of the name — one that hits triple digits within a half-dozen years or less — will be devilishly more difficult. Consider these differences between New York congestion pricing and national carbon taxing:

-

- The economic incidence of NY congestion pricing is far more income-progressive than national carbon pricing. A bulwark of CP advocacy here has been unstinting support from the Community Service Society — the city’s and nation’s oldest antipoverty NGO. It’s hard to picture comparable support for nationwide carbon pricing. Not even “dividending” carbon revenues, which CTC strongly supports, can guarantee that millions of U.S. households won’t pay more in higher fuel costs than they’ll get back in monthly carbon dividends. Inevitably and unfortunately, some will slip through the dividend’s safety net, allowing opponents to cast even the most judicious revenue treatment for carbon taxing as insufficient to protect the poor.

- NY congestion pricing comes with a natural route for managing the congestion revenues: investing them in long-term mass transit improvements. It was this facet, more than the promise of lessened auto traffic, that brought the city’s rich tapestry of transit advocates into the fore of the congestion pricing campaign. Even motorists — some of them, anyway — grasp improved transit’s value to them as a means of dissuading others to invade “their” road space. National carbon pricing has no such obvious path for distributing or investing its revenues. Sure, spending carbon revenues on renewables and efficiency, particularly in historically disadvantaged communities, has a nice ring, but in practice there’s no clear carbon revenue spending path that won’t disaffect vast numbers of stakeholders. Now factor in the orders-of-magnitude difference in annual dollars — a billion or so in the case of NY congestion pricing vs. half-a-trillion for a comprehensive triple-digit U.S. carbon tax. Talk about a donnybrook gap!

- America’s geographic vastness and cultural separateness make it nearly impossible for citizens to consistently find common ground, as evidenced by our red-vs.-blue and urban-vs.-rural polarization. Even as New York City’s sense of conjoined fate has frayed somewhat, many residents still manage to cultivate a sense of connectedness to each other. Nationally, that ship has sailed. Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” anthem is 80 years old. Fond hopes from the 1990s or early 2000s that combating climate change might re-invigorate Americans’ shared humanity seem almost as distant.

Antidotes

To these three difficulties we have three antidotes.

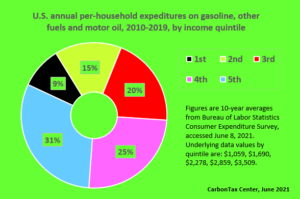

Over the prior decade, the wealthiest U.S. household quintile spent 3.3 times as much on gasoline as the poorest — evidence of the power of carbon dividends to more than offset the natural regressivity of higher energy prices.

The first is the power of carbon dividends. Even if they can’t keep whole every single low-income U.S. household — there are, after all, 65 million below-median-income families, each with its own consumption profile — the vast majority of those households will reap more in dividends than they’ll pay with the carbon tax. Not just that, the dividend approach bypasses political fights over where and how to invest the revenues.

A second possible antidote is the exigency of the climate crisis itself. Unlike NYC traffic congestion or failing transit, which public policies like congestion pricing can vanquish going forward, climate collapse can’t be reversed. This ineluctable fact could, or should, motivate climate advocates to re-evaluate their largely ideological objections to robust carbon pricing (which we discuss elsewhere in terms of climate justice campaigners and self-identified progressives). Given that people of color, whether in the U.S. or the Global South, are disproportionately vulnerable to climate chaos, hope remains that carbon-pricing opponents may reconsider their antipathy to the most efficacious policy for slashing emissions and actually protecting the populations they profess to care about.

The third, as always is organizing. Carbon-taxing proponents need to keep up the pressure. We also need to expand our tent, as we wrote about last month in Gainsharing: Carbon Taxes Can Put Clean Energy Back in the Black. We’ll have more to say soon on that score.

Since climate progress is stalled, let’s unload on fee-and-dividend

Someone chose an inopportune time to beat up on carbon taxing’s fee-and-dividend variant. Not U-C Santa Barbara political scientist Mitto Mildenberger, whose paper, Limited impacts of carbon tax rebate programmes on public support for carbon pricing, co-authored with scholars from Montreal, Vancouver and Bern (Switzerland), appeared this week in the prestigious journal, Nature Climate Change. No, I mean iconoclast blogger David Roberts, who used Mildenberger’s provocative paper as a launching pad to again dunk on carbon pricing and people who still hold out hope for it.

Roberts’ post, Do dividends make carbon taxes more popular? Apparently not., published on Monday on his Volts platform, gets off on the wrong foot right away, claiming:

Economists have long insisted that pricing carbon is the most efficient way to reduce greenhouse gases. For years, they hijacked the climate discourse, with untold money and effort put behind proposals for various increasingly baroque pricing schemes, to very little effect. (emphasis added)

Roberts may be right about efficiency and economists, but his description doesn’t fit climate hawks like Citizens Climate Lobby and Carbon Tax Center. We place our chips on carbon taxes not on account of their economic efficiency but because of their unrivaled potential to slash carbon emissions quickly in the U.S. — and also their global portability.

The meat of Mildenberger’s paper and Roberts’ post, distilled in their respective titles, is that in the only two countries with some form of fee-and-dividend carbon pricing, not just public support but basic awareness of the programs, particularly the dividends themselves, is middling at best.

We think this “finding” is both questionable and beside the point. Let’s take a close look at each of those countries: Switzerland and Canada.

Switzerland

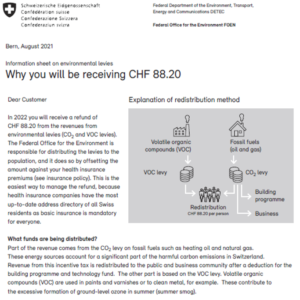

Official Swiss notice of this year’s carbon dividend. At the current 1.09 exchange rate, 88.20 CHF = $96.14.

Switzerland’s carbon tax began in 2008 and reached its current level of 96 Swiss francs per metric ton in 2018. Converting metrics and currencies, that equates to $95 per ton of CO2, the kind of level that carbon taxers dream about. According to CTC’s carbon tax model, if the U.S. next year started a $15/ton carbon tax and ramped it up to reach $95 in 2030, emissions in that year would be 33% less than in 2005, taking us 2/3 of the way to the Biden target of halving 2005 emissions in 2030.

Not only that, a U.S. carbon tax at the Swiss level of $95 a ton would generate a carbon dividend in 2030 of $1,500 per person, even allowing for reduced emissions and a larger population and equal shares for children. Surely, a $1,500 carbon check — or, if you prefer (and we do) 12 monthly carbon dividends of $125 per person — would translate into strong and rising popularity, especially considering that a majority of people and households would be expending less than those amounts in increased direct and indirect energy costs.

That’s the straw man. The reality is that Switzerland’s $95/ton (U.S.) carbon tax will deliver only $96 in per-person dividends for the entire year. (See document at left, downloadable here.) That’s less than one month’s worth of what U.S. residents would receive under a full fee-and-dividend scheme for a Swiss-level $95 carbon tax. In that light, it should be no surprise that Mildenberger and his co-authors didn’t find residents of Geneva or Zurich dancing in the streets over their carbon dividends. In U.S. terms, Swiss residents’ 2022 carbon tax dividend is what Americans would get in 2030 from a piddling carbon tax of $5.50 per ton of CO2.

Why the discrepancy? Why is Switzerland’s carbon dividend only 1/15 as great as what a U.S. dividend would be from a carbon fee of the same level?

Excerpt from Switzerland Federal Office for the Environment document, “The Swiss Approach to Carbon Pricing,” May 2021.

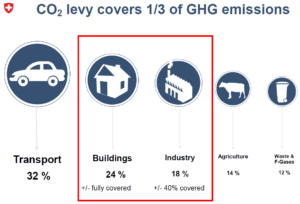

There are four big reasons. First, Switzerland’s energy consumption is far less per capita than that of the United States. Second, hydro-electricity rather than carbon-based fuels like coal and methane powers the country’s grid. Third, the Swiss carbon tax exempts transport and agriculture and more than half of Swiss industry (see graphic at right; full document here). Fourth, part of the tax revenue is siphoned off by businesses before the dividends get calculated.

No wonder, then, that Switzerland’s carbon dividend is so meager. Consider further that, as Mildenberger et al. point out, “Citizens receive their rebates as a discount on their health insurance premiums, with annual notifications about this monthly benefit through health insurance forms.”

Annual notifications through health insurance forms. This is reasonable, even enlightened, public policy. It’s also almost diabolically designed to obfuscate the dividend side of the carbon fee coin.

Canada

Canada’s carbon tax is far more complicated than Switzerland’s. When we last updated CTC’s Canada page, in March 2011, we characterized carbon pricing in the country’s 13 provinces as follows:

- Six provinces, including Ontario and Alberta, were covered by the federal pricing scheme that would reach $50/tonne in 2023 — around $36/ton in U.S. terms — and then ramp up sharply to $170/tonne by 2030.

- Four were deploying their own carbon tax, led by British Columbia, which inaugurated the Western Hemisphere’s first meaningful carbon tax in 2008.

- Quebec and Nova Scotia were part of a two-country carbon cap-and-trade program that is anchored by California.

- New Brunswick employed an output-based carbon pricing system.

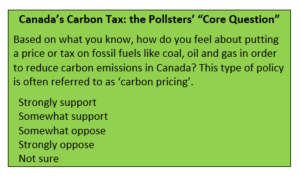

Wording courtesy of UCSB Prof. Matto Mildenberger, lead author of the Nature Climate Journal article discussed here.

Given this patch-quilt, as well as the novelty of carbon pricing in most of Canada, it seems to us unsurprising that polling that commenced in February 2019 (and extended through May 2020, with five “waves” in all) would yield the mixed results reported in the Midenberger paper: upticks in two provinces, Ontario and British Columbia, and downturns in the other three, Quebec, Alberta and Saskatchewan.

The “core question” asked in the Canada polling, as described by lead author Mildenberger, who graciously shared it with us yesterday via email, is shown at left. The language is neutral, perhaps to a fault. It offered no affirmative spin, such as “Canada recently began taxing fossil fuels in order to protect the climate, with the money rebated in ways that will help households get ahead financially.” That kind of favorable tilt could perhaps be justified as necessary to counter the negative vibe surrounding taxation generally.

To be sure, that negative vibe is precisely what drives pundits like Roberts to deride carbon taxing, as he did in the second and third paragraphs of his post:

Over time, political experience with carbon taxes has highlighted a truth that should have been obvious long ago: carbon taxes are taxes, and people don’t like taxes. People don’t like paying more money for stuff.

More broadly, carbon taxes are an almost perfectly terrible policy from the perspective of political economy. They make costs visible to everyone, while the benefits are diffuse and indirect. They create many enemies, but have almost no support outside the climate movement itself. All the political intensity is with opponents.

We get it. We know full well the albatross that taxation always bears. But we also know that taxes on “bads” have been enacted into law. The U.S. government taxes cigarettes, as does every state. New York City taxes grocery bags, and Philadelphia and Berkeley, CA tax sugary soft drinks.

Obviously, taxing something as supercharged financially and culturally as fossil fuels is a much heavier lift, as evidenced by the absence of explicit carbon taxing anywhere in the fifty states. (We exclude federal and state motor fuel taxes, due to their tie-in to roads rather than health or climate; we also exclude New York State’s Petroleum Business Tax, though its support of NYC metro-area transit perhaps merits an honorable mention; conversely, New York City’s congestion pricing program, now scheduled to begin in 2023, will create a strong template for carbon taxing, as we’ve pointed out many times, including in The Nation magazine in 2019.)

So yes, carbon taxing — not fig-leaf $20/ton-and-no-higher carbon taxing a la Exxon or the occasional Republican, but a levy rising steadily to triple digits before 2030 — is hard stuff. But so is just about every other decarbonization policy or program, especially if done at scale.

Well-heeled NIMBY’s have whittled down wind projects for years; now, so too may supply-chain problems. Rooftop solar endures pushback not just from utilities and their high-wage unions but also from concerns that lower-income residents could gett stuck with higher utility bills. Only splinters of President Biden’s Build Back Better plan, which wasn’t going to be able to deliver its promised 50% cut in emission by 2030 anyway, will pass, thanks to one or two Democratic senators and 50 Republicans. Even the push to electrify everything may find its vaunted carbon benefits a good deal less potent than advocates imagine, an issue we intend to explore in a future post.

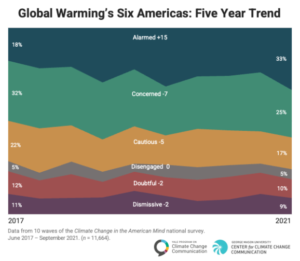

A record one-third of Americans in the latest “Global Warming’s Six Americas” are “alarmed” by climate change.

Still, though, the biggest misdirection in the Mildenberger et al. paper and the Roberts post may be their fretting over public opinion in the first place. The public doesn’t have to love carbon fee-and-dividend. It simply needs to embolden political leadership that will enact it (and the raft of complementary policies) into law and ensure that the fee, which shouldn’t be set too high to start, can keep rising over time.

Public opinion increasingly supports climate action, not tepidly but “with alarm,” as the latest Yale – George Mason opinion survey of “Global Warming’s Six Americas” attests (see graphic at right, and more detailed treatment with link here). It’s past time for carbon pricing naysayers to throw off their ideological blinders and get behind policies that can pass and deliver.

PS to David Roberts: Contrary to your Volts post, fee-and-dividend did not “los[e] badly in a public referendum in 2016.” What went down to defeat in Washington state was a sales tax swap of the carbon revenues, necessitated by the state’s constitutional prohibition against dividend-type state tax treatments. And what doomed the proposal was opposition from climate hawks who took umbrage at being leapfrogged politically, and in revenge brought in lefty heavy hitters to slime the measure. But that’s another story.

Huge hat tip to friend of CTC Drew Keeling for Swiss materials and perspective. Drew’s most recent Carbon Tax Center post, Rural disgruntlement, pro-climate complacency sink expansion of Swiss carbon tax, appeared in June 2021.

Where Carbon Is Taxed (Some Individual Countries)

This page reports on carbon taxes that have been enacted (and in one case, enacted and withdrawn) in:

Canada has its own page, where we summarize its nationwide carbon price and also report in detail on British Columbia’s carbon tax, the Western Hemisphere’s (if not the world’s) most comprehensive and transparent carbon tax.

European Union: Emissions Trading System

The European Union (EU) implemented a carbon cap-and-trade system in 2005. The EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) is the world’s first international emissions trading system, operating in all EU member countries plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

The EU ETS covers over 10,000 stationary emitters — mostly power stations and industrial plants. It also covers domestic and intra-EU air travel. In toto, the ETS covers around 40 percent of the EU’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, making it the largest carbon cap-and-trade program in the world, covering approximately 1.5 billion metric tons of CO2 per year.

For much of its existence, the ETS was largely ineffectual because its emissions caps were too high and granted large numbers of free allowances to big polluters. Concern about carbon leakage — polluters from the EU potentially going elsewhere to do their polluting, hence, “leaking” carbon from the EU — drove the EU to implement free allowances as its primary method of allocation back in 2005. As a result, polluters obtained large numbers of allowances — in 2013, manufacturers received 80% of their allowances for free — and many were able to maintain a surplus.

Compounding the problem of giveaways, the EU grossly overestimated future CO2 emissions in setting the cap amounts, resulting in a too-high number of allowances. In the first phase of the EU ETS, from 2005-2007, only three member states had caps lower than baseline 2005 emissions levels. And with the 2008 financial crisis driving emissions down, the caps were rendered even more useless.

Background

In December 2019, the European Commission — the executive branch of the EU — introduced the European Green Deal, an ambitious climate policy package with the general goal of at least 50% GHG emissions reductions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2050. The European Green Deal represents the EU’s main legislative effort to meet its commitments under the Paris Climate Agreement. The Green Deal included the ETS as an integral part of its action plan.

In 2020, the EU expanded to a 55% reduction its commitment to reduce emissions 40% from 1990 levels by 2030 and. The ramp-up came in December 2020, following all-night negotations in which the EU committed to helping coal-heavy countries like Poland meet individual-country commitments.

The U.K.’s concurrent exit from the EU and ETS caused a substantial exit of low-carbon power producers, resulting in an increase in average carbon contents for the remaining EU power producers. It’s not yet clear how these changes will play out, as the U.K. has not announced plans to link with any other carbon trading systems.

How the ETS Works

The European Trading System implements an emissions cap for the overall volume of GHG that may be emitted by covered airlines, power plants and factories. Emitting companies purchase at auction — or receive — tradable allowances, the total number of which is capped at a level that steadily decreases each year. Since 2013, the emissions cap has applied to the EU as a whole, not individual countries. The current cap for 2021 on GHG emissions from these stationary installations is 1.57 billion tonnes per year, or roughly half of 2019 CO2 emissions for the entire European Union, including the U.K.

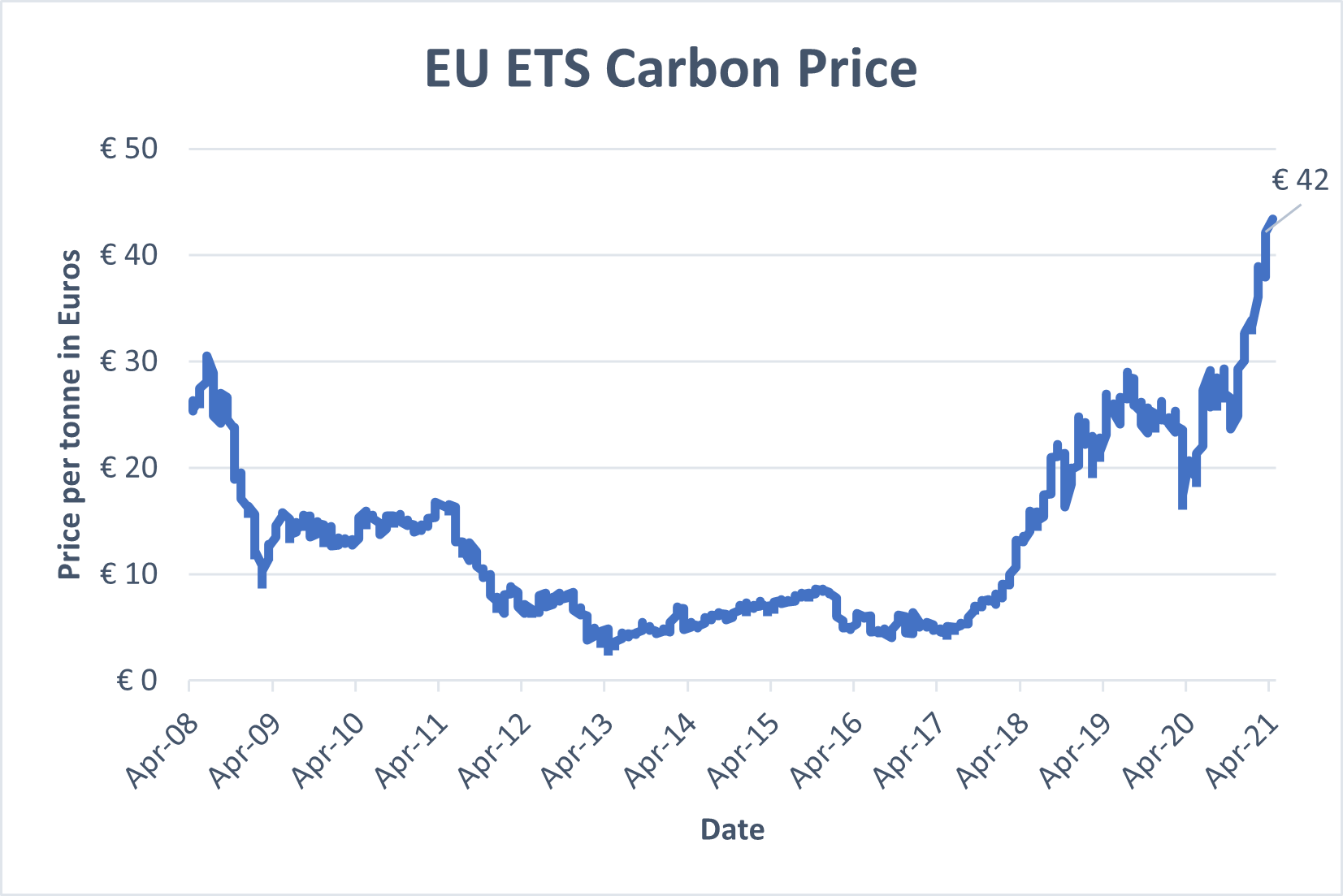

Data from https://ember-climate.org/data/carbon-price-viewer/

The price of a carbon allowance has roughly doubled in the past several years, reaching a high of nearly €43 in March 2021. BloombergNEF (New Energy Finance) projects that prices will hit €100 by 2030. The higher price levels enable the ETA to “arguably serve its purpose by making it too expensive for emitters of fossil fuels to continue business as usual,” as reported in early 2021 by Alessandro Vitelli of Montel News.

Since January 2019, the EU ETS has included a market stability reserve (MSR), which maintains any surplus of allowances, allowing for adjustments to the supply of allowances up for auction, if needed. Unallocated allowances are transferred to the reserve, which is operated under strict rules that bar meddling by the Commission or Member States.

Phases

The ETS’s 15-year tenure to 2020 may be divided into three phases.

- Phase 1, from 2005-2007, served as a pilot of “learning by doing.” During that phase, about 12,000 installations received permits to emit about 2.2 billion tons of CO2, nearly half of EU CO2 emissions at that time. Most allowances were given for free.

- In Phase 2, 2008-2012, the cap on allowances was reduced by 6.5% compared to 2005. Phase 2 aligned with the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, when countries in the EU ETS had to fulfill commitments to reduce emissions by an average of 5% below 1990 levels. (The EU and its member countries ended up cutting emissions by 8% below 1990 levels.) Several countries held auctions.

- Phase 3, 2013-present, saw the application of a single, EU-wide cap on emissions instead of the previous system of national caps. Auctioning replaced free allocation as the default method of allowance allocation. Phase 3 also brought more sectors and gases under the EU ETS umbrella. During this phase, the EU-wide cap on stationary installations decreased by 1.74% each year.

For Phase 4, from 2021-2030, the Commission revised and strengthened the EU ETS in 2018. The overall number of emission allowances will now decrease at an annual rate of 2.2%, instead of 1.74%. However, significant amounts of free allowances remain, ostensibly to combat carbon leakage. The EU will still give 100% free allocation to sectors at the highest risk of relocating production outside the EU. For industries less likely to flee, free allocation will be phased out, from a maximum of 30% in 2026 to zero by 2030. Overall, the EU predicts 6 billion free allowances will be granted from 2021-2030.

Impact

The EU ETS’s specific targets are to reduce GHG emissions by 21% between 2005 and 2020, and by 43% by 2030.

Total EU emissions of greenhouse gases fell by 23 percent from 1990 to 2018, according to the European Commission. Emissions from ETS sectors alone fell 33% from 2005-2019.

Carbon leakage

In its Green Deal statement, the European Commission addressed the concern that countries across the world will continue to have “differences in levels of ambition,” by pledging to propose a carbon border adjustment mechanism as an alternative to the ETS’s carbon-leakage measures. As Inside Climate News explains carbon border adjustments:

Economists have long suggested that there’s a way to break that global impasse [on climate action] — and that’s to treat carbon like any other international trade dispute. Impose tariffs or quotas on imports from countries that have given their manufacturers an unfair advantage of uncontrolled carbon emissions.

In March 2021, the European Parliament adopted a resolution favoring a carbon border adjustment mechanism. The European Commission will propose legislation in June 2021.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom — England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland — has maintained a carbon tax since 2013. Technically, the tax is a “carbon price floor” (CPF) that functions as the minimum price that fossil fuel producers pay for emitting CO2. The CPF applies to energy-intensive industries only and is not economy-wide.

There have been several calls lately to tax carbon emissions in the U.K. at a higher rate and on a broader scale. Grantham Institute researchers Josh Burke and Esin Serin argued in a fascinating Feb. 2021 opinion piece that carbon pricing should be enacted not as a stand-alone but “as part of a significant and broad package of post-COVID fiscal reforms.”

History

As a result of the 2008 Climate Change Act — passed with overwhelming support across parties — the U.K. was required to drastically reduce its carbon output according to five-year carbon budgets. Unsurprisingly, the U.K. — birthplace of classical economics and home base of Sir Nicholas Stern, the renowned economist who in 2007 famously called climate change “the result of the greatest market failure the world has seen” — turned to carbon pricing to carry part of the load.

In 2009, the Department of Energy and Climate Change released a report, “Carbon Valuation in UK Policy Appraisal: A Revised Approach,” detailing reasons to adopt a carbon price. Witnesses at the 2009-2010 Environmental Audit Committee’s report on Carbon Budgets called for a carbon price floor, but the Labour government opposed the idea. Then in 2010, the Coalition government consulted on proposals for a CPF, and the measure was introduced in the 2011 Budget for implementation in 2013. The 2011 Budget framed the CPF as a way to “drive investment in the low-carbon power sector” and “support the long-term stability of the public finances.” The government also said the CPF “achieves the right balance between encouraging investment without undermining the competitiveness of UK industry.”

When the carbon floor was introduced, the Confederation of British Industry and Renewables Energy Association were supportive, but the measure also found criticism from several sides that argued it was, by turns, ineffective, expensive, and uncertain for investors. But the government framed the tax as the best move for consumers, stating that the “market-based approach to pricing carbon provides the most efficient and cost-effective policy framework to meet our environmental goals.”

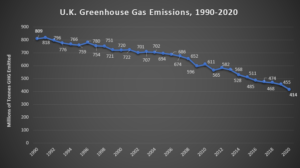

Data from U.K. Gov’t Energy Trends. Data exclude international aviation, shipping and emissions in producing imported goods.

Less than 10 years after implementing the CPF, the U.K. is halfway to meeting its goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. U.K. GHG emissions in 2020 were 51% below 1990 levels, putting the country mathematically on track to reach net zero by 2050.

30 Years of Falling Emissions

The first graph makes clear that this 2020 milestone is only slightly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The 2020 decline in emissions, though severe, roughly 40 million tonnes, was no greater than that in 2014 (also 40 million tonnes) and was less than the 56 million tonne drop in 2009, during the severe recession. Emissions fell in almost every year from 1990.

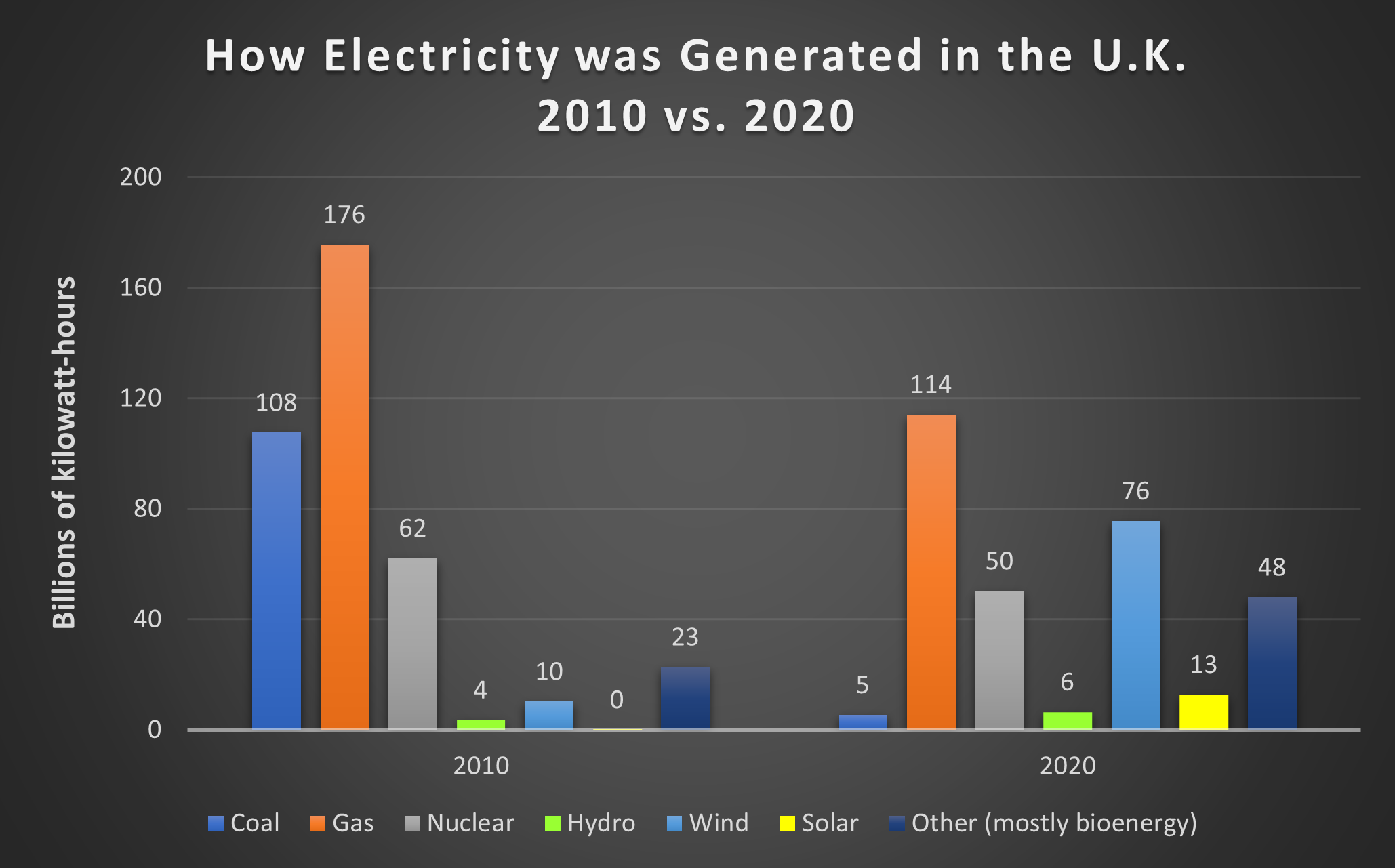

Data from Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy: Dataset for quarterly and monthly supply and consumption of electricity, Table 5.1.

The anticipated recovery from COVID-19 will, of course, provoke a partial rebound in emissions. The national government’s March 2021 Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy specifies that industrial emissions must fall by two-thirds before 2035 to enable the U.K. to meet its Dec. 2019 pledge — the first by a major economy in the world — to reach net-zero GHG emissions by 2050.

What accounts for the huge drop in U.K. greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 to 2019? Carbon Brief credits three changes for around 90% of the decline:

- Electricity that doesn’t rely on coal – 43% of electricity was generated by renewables in 2020 (“renewables” does not include nuclear power, but it does include wind, hydro, solar, and bioenergy).

- Cleaner industry and a shift away from carbon-intensive manufacturing.

- A pared-down, cleaner fossil fuel supply industry.

It’s important to note, however, that a considerable amount of U.K. “renewable” electricity is generated by burning biomass, i.e. wood pellets. Inclusion of bioenergy as a renewable source of energy is at best contentious and more likely a scam, as journalist Michael Grunwald pointed out in his March, 2019 expose in Politico.

U.K. Carbon Pricing: Details

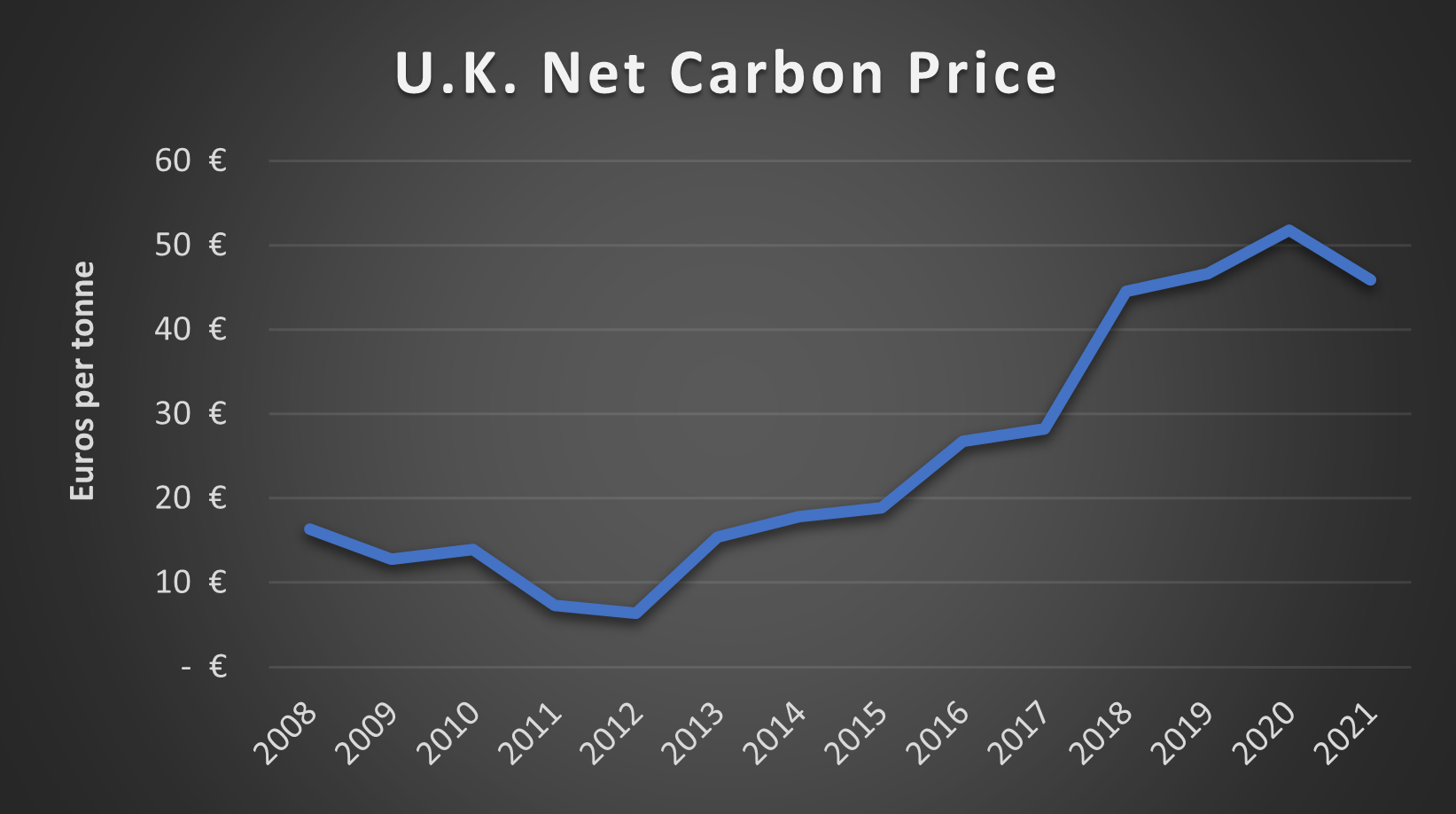

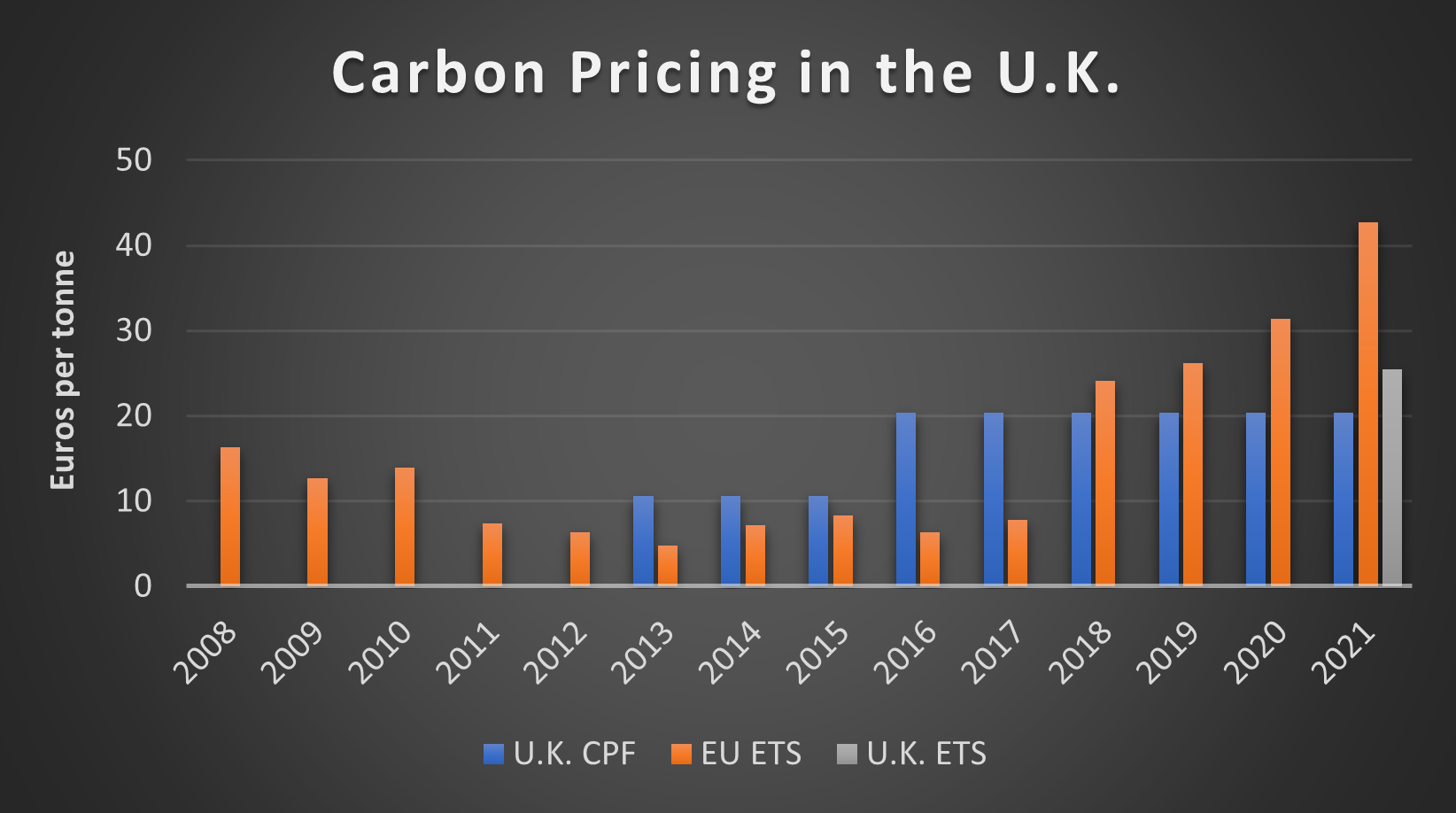

Data from https://ember-climate.org/data/carbon-price-viewer/ and https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn05927/

Initially priced at £16/tonne in 2013, the U.K.’s carbon price floor (CPF) was set to increase to every year, hitting £30/tonne by 2020 and £70/tonne in 2030, but was capped in 2015 at £18.08/tonne until 2021 (20.40 euros at the 2015 exchange rate). The CPF has impacted the generation fuel mix significantly; coals share fell from 41% in 2013 to less than 8% in 2017.

Brits sometimes call their CPF a “top up” tax since it was intended to top up European carbon pricing in the form of the EU emissions trading scheme (ETS). The U.K. finished its Brexit transition from the EU at the end of 2020, creating the need for a new, non-EU emissions trading scheme (ETS).

The U.K. announced in February 2021 that it would launch its own carbon trading scheme in May 2021. The U.K. government says their ETS replaced the UK’s participation in the EU ETS as of January 1, 2021, but the first U.K. ETS emissions auctions will not begin until May 19, 2021.

According to Auctioning Regulations released in February, bids will follow a minimum Auction Reserve Price (ARP) of £22/tonne when they begin in May, but the price will increase: “The government will consult on its intent to withdraw the ARP as part of the planned consultation to appropriately align the U.K. ETS cap with a net zero trajectory which will be launched later this year.”

Data from https://ember-climate.org/data/carbon-price-viewer/ and https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn05927/

The floor for the U.K. ETS was initially set to 15 pounds but raised to 22 pounds per tonne, perhaps following some form of the logic suggested by climate advocacy group Ember: “The EU ETS has averaged a price of around £22/t (€25/t) over the last two years, so it would make sense to set the U.K. carbon price floor to at least that level, especially with further reform to strengthen the EU ETS price due in the coming year.”

The U.K. government stated in the Autumn Budget 2017 that they were “confident that the Total Carbon Price, currently created by the combination of the EU Emissions Trading System [of 7.78] and the Carbon Price Support [of 20.40], is set at the right level, and will continue to target a similar total carbon price until unabated coal is no longer used.”

Ireland

(Thanks to Wesleyan University environmental studies major Nicholas J. Murphy for expanding this section in July 2015.)

Ireland enacted a carbon tax in 2010 under a coalition government of its Green Party, Fianna Fáil (one of Ireland’s two mainstay center-right parties) and the Progressive Democrats. Originally designed to provide a double dividend by offsetting income taxes, the revenue was re-allocated to satisfy the diktats of the Troika — the triumvirate of the European Commission (EC), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and European Central Bank (ECB) that administered the austerity policies on EU member nations bailed out during the 2008 debt crisis. (See OECD working paper on Ireland’s Carbon Tax and the Fiscal Crisis.)

The effect is arguably similar, since income taxes would have had to rise, absent the carbon tax revenues. Frank Convery, an economist at University College Dublin considered the foremost expert on Ireland’s carbon tax, writes enthusiastically:

Ireland is a pioneer in the implementation of a carbon tax. This has allowed us to avoid (more) increases in income tax which would have further reduced disposable income, increased labour costs and destroyed jobs. It is also facilitating us in meeting our very demanding legally binding obligations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and provides support for the creation of new jobs in improving energy efficiency and growing the low carbon economy.

Ireland’s carbon tax covers nearly all of the fossil fuels used by homes, offices, vehicles and farms, based on each fuel’s CO2 emissions. It began in 2010 at €15/ton and rose to €20/ton in 2012, where it remains today. Solid fuels (coal and peat) were added in 2013 at €10/ton after concerns from agricultural interests were resolved, and that price has since risen to match the €20 price on other fuels. The tax generates roughly €100 million in revenue per €5 of tax, meaning it currently draws about €400 million annually.

The carbon tax has been complemented by other environmental taxes based on vehicle fuel efficiency and domestic landfill waste, as New York Times environmental correspondent Elisabeth Rosenthal reported in Dec. 2012, in Carbon Taxes Make Ireland Even Greener:

Over the last three years, with its economy in tatters, Ireland embraced a novel strategy to help reduce its staggering deficit: charging households and businesses for the environmental damage they cause. The government imposed taxes on most of the fossil fuels used by homes, offices, vehicles and farms, based on each fuel’s carbon dioxide emissions, a move that immediately drove up prices for oil, natural gas and kerosene.

Household trash is weighed at the curb, and residents are billed for anything that is not being recycled. The Irish now pay purchase taxes on new cars and yearly registration fees that rise steeply in proportion to the vehicle’s emissions.

Environmentally and economically, the new taxes have delivered results. Long one of Europe’s highest per-capita producers of greenhouse gases, with levels nearing those of the United States, Ireland has seen its emissions drop more than 15 percent since 2008. Although much of that decline can be attributed to a recession, changes in behavior also played a major role, experts say, noting that the country’s emissions dropped 6.7 percent in 2011 even as the economy grew slightly.

Notably, the Irish carbon tax was designed to fill gaps left by the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), which addresses only large polluting firms and accounts for only roughly 40% of emissions sources while being hampered by volatility. The case of Ireland demonstrates the potential for EU-wide cooperation in setting an effective harmonized price on carbon in preference to a piecemeal and volatile ETS.

The elements of Ireland’s carbon tax introduced in 2010 are specified in the Finance Act of 2010. (See Part 3 (Customs and Excise), Chapters 1 (Oil), 2 (Natural Gas), and 3 (Solid Fuels) for tax rates and other provisions.)

Ireland’s Vehicle Registration Tax is also partly emissions-based. A VRT Calculator on the Irish Tax & Customs website provides a means to estimate the amount of tax on a vehicle based on Make/Model/CO2 Emissions. Interestingly, the CO2-sensitive VRT has touched off a pronounced shift to diesel vehicles, which emit less CO2 but more of other pollutants with localized health impacts. Changes to the tax rate in Budget 2013 are detailed here.

Finally, the law firm Arthur Cox offers these useful guides ([1] & [2]) to Ireland’s carbon tax.

Australia

The widespread wildfires devastating much of Australia in the Southern Hemisphere’s 2019-2020 summer have drawn worldwide news coverage and cast that country’s retrograde official climate stance in appropriately harsh light. CTC’s blog post, Australia’s Brief, Shining Carbon Tax distilled and updated the information below and also revealed the stunning detail that the two years in which Australia had a national carbon tax, 2012-2014, saw dramatic drops in CO2 emissions, both absolute and relative to GDP (see graphic directly below, at left). As of this mid-January writing, however, no other media had picked up this finding.

The Liberal Party government of PM Scott Morrison has come under withering attack for hewing to the climate-denying line of the Murdoch-dominated press that alternately blames the fires on arsonists and wildland “mismanagement” while hand-wringing that unilateral action to curb Australia’s emissions would have little or no discernible impact because the country accounts for only 1 percent of global CO2. The Daily Beast has reported that James Murdoch, the media baron’s younger son, was sharply critical of Fox News and News Corp’s “climate-change denial,” while Australian union organizer James Raynes posted the ironic tweet shown at right.

Our earlier coverage of Australia carbon taxing, though somewhat dated, is below. Be sure to read our Jan. 7 (2020) post.

Australia instituted a carbon tax on July 1, 2012 and repealed it two years later, on July 17, 2014. Both events were milestones. Though some countries, notably Sweden, have had longer-standing and stronger national carbon levies, Australia’s was the first explicit national tax on carbon emissions. The repeal was also precedent-setting, and predictably it has garnered far more global attention (and hand-wringing) than did the tax itself.

The tax level, $23 per tonne (metric ton), equated to $19.60 per U.S. ton of CO2, at the U.S.-Australian dollar exchange rate (1.00/0.94) in July 2014.

As recounted by Australian journalist Julia Baird in a 2014 NY Times op-ed, A Carbon Tax’s Ignoble End: Why Tony Abbott Axed Australia’s Carbon Tax, published a week after Australia’s Senate voted for repeal, the tax was a political stepchild, opposed by the country’s two major political parties, left-leaning Labor and center-right Liberal, and brokered by the Greens during a period of governmental stalemate in 2011-2012:

In 2010, the Labor prime minister, Julia Gillard, said she would look at carbon-pricing proposals, but also promised, “There will be no carbon tax under the government I lead.” Then, under pressure to form a minority government, she made a deal with the Greens and agreed to legislate a carbon price: a tax by any other name.

The heat, anger and vitriol directed at her as a leader — and as Australia’s first woman to be prime minister — coalesced around the promise and the tax. It grew strangely nasty: She was branded by a right-wing shockjock as “Ju-Liar,” a moniker she struggled to shake. The political cynicism surrounding the carbon tax certainly reduced Ms. Gillard’s political capital, but it was a perceived lack of conviction in the policy itself that damaged the pricing scheme’s credibility.

See also Australian ABC News’ superb Timeline of the tax’s torturous political path, posted in July 2014.

Predictably, the Times’ news dispatch, Environmentalists Decry Repeal of Australia’s Carbon Tax, cast the repeal as greens vs. economy, ignoring the reductions in carbon intensity in the power sector (which helped blunt the tax’s cost) as well as provisions that directed revenues to households to mitigate consumer impacts (see below).

Australia’s carbon tax also imposed climate-equivalent fees on methane, nitrous oxide and perfluorocarbons from aluminium smelting, and was collected from roughly 500 of the nation’s biggest emitters, according to the Big Pond Money blog. These included electricity generation, stationary energy producers, mining, business transport, waste and industrial processes; some (non-electric) industries were eligible to receive trade-exposure based assistance, according to the same source. Most if not all road transport fuel (i.e., petrol) was exempt. The tax level was indexed to inflation and rose from the initial $23.00 (Australian) per tonne to $24.15 per tonne in 2013 and $25.40 in 2014. Beginning July 1, 2015 the price was to be set by a cap-and-trade system linked to the EU ETS (whose price has fallen below $10/T CO2). PolitiFact Australia compared the size and breadth of its carbon tax with others around the world, neatly refuting the Liberal Party’s pejorative characterization of the tax as “the world’s largest.”

In May 2013, one of Australia’s major papers, the Age, reported that national electricity generation with highly polluting lignite coal had fallen 14% vs. the same year-earlier period in the tax’s inaugural nine months, with conventional coal-fired generation also falling, by nearly 5%. During the same period, renewable electric generation “soared” by 28% and electricity output from lower-carbon methane increased by 9.5%. While factors such as greater hydro-electricity availability, flooding of a major coal mine, and implementation of a 20% renewable-energy target probably contributed to the declines in coal use, the 2.4% reported drop in overall electricity generation suggests that the carbon tax played a part.

Overall, reported the Age in the same article, “the emissions intensity of the national electricity market has fallen 5.4 per cent since the carbon price was introduced [presumably over the nine months extending from July 2012 through March 2013], meaning carbon emissions from power generation is [sic] down 7.7 per cent, or 10 million tonnes, from the previous nine months.”

Similar statistics were reported earlier, in Jan. 2013, by “The Australian” newspaper. The “big change in the mix of power” was attributed to “much greater use of renewable energy from hydroelectricity from the Snowy Mountains and Tasmania, and also wind farms.” The same source also said that “The retreat of manufacturing has been a factor, with the closure of the Kurri Kurri aluminium smelter last year and cutbacks in other metals plants affecting industrial demand.” A consultant cited by The Australian added that “the spread of roof-top solar panels and of appliances that used less energy were reducing growth in household consumption” of electricity, while another consultant, pointing to reduced electricity generation and emissions, said that “changes of this scale are without precedent in the 120-year history of the electricity supply industry.”

According to “The Australian,” the power sector accounted for about half of Australia’s emissions and a larger share of the carbon tax, because some of the largest emitters have free permits.”

Use of the carbon tax revenues was complex. Some went to the Australian Renewable Energy Agency for project funding and other monies providing “a raft of other compensation and development funds focused on biodiversity, low carbon agriculture, small business grants and support for indigenous communities,” according to Big Pond Money. More than half of the revenue was said to be earmarked to support low and middle income households to cover the increase in prices that business will pass on to consumers. The government also acknowledged, according to Big Pond Money, that the carbon tax would take more from 3 million households than it would return, while 2 million households would be no worse off and 4 million households better off. A Household Assistance Estimator developed by the authorities was said to provide a means for families to estimate how they would fare financially under the carbon tax.

A later AP story hammered Australia’s carbon tax, asserting that “Voters have never stopped hating the tax and its effect on their electric bills” and predicting that it would doom the ruling Labor Party in the Sept. 8, 2013 elections. “Longtime Labor Party supporters — even people who have helped cut pollution by installing solar panels at home — have flocked to the opposition,” AP reported, in Australian Gov’t Faces Carbon Tax Backlash at Poll (Sept. 6, 2013). “The government estimated the tax would cost the average person less than AU$10 per week,” said AP, “but three months after it took effect, most Australians surveyed by policy think-tank Per Capita said it was costing them more than twice that much. But they also expressed confusion, with most blaming the tax for higher gas prices even though it is not levied on motor fuel purchases.” In an e-mail, cap-and-dividend proponent Peter Barnes blamed the tax’s unpopularity on the absence of “100% dividends, fully transparent and highly visible.” We don’t disagree.

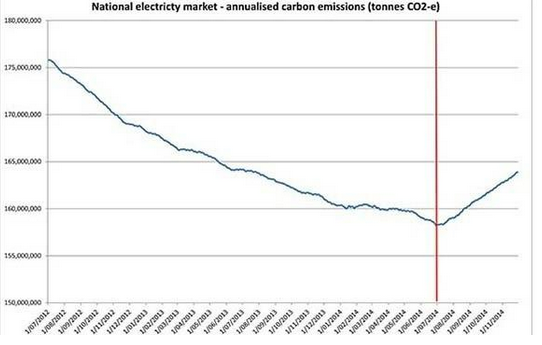

Update (January 2015): In case anyone doubted the effectiveness of taxing carbon pollution, the following graph of power plant CO2 emissions published in Australia’s Guardian shows what has happened in the year since the tax was repealed. The vertical red line is the repeal date.

See also, Emissions for power sector jump as carbon tax ends (Sydney Morning Herald, 1/7/15).

Chile

In October 2014, Chile enacted the first climate pollution tax in South America. It’s a modest levy — a mere $5 per metric ton of CO2 — that applies to only 55% of emissions. Moreover, it doesn’t take effect until 2018. Still, it’s a positive first step. The NY Times reported these details:

Chile’s tax, which targets large factories and the electricity sector, will cover about 55 percent of the nation’s carbon emissions, according to Juan-Pablo Montero, a professor of economics at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, who informally advised the government in favor of the tax. At $5 per metric ton of carbon dioxide emitted, Chile’s tax is lower than the $8-per-metric-ton carbon price in the European Union’s carbon-trading system, which has often been criticized as too lax. But it is higher than a carbon tax introduced in Mexico in January.

“We all understand we need to go way beyond the $5 mark” in order to really reduce carbon emissions, Dr. Montero said. However, he added, “I think this still allows you to start building the institutions that you need in the future, when you start moving forward toward more ambitious goals.”

Chile’s tax was enacted as part of a broader tax reform and revenue measure, according to the Times:

Chile’s approval of a carbon tax owes much to its positioning inside a broader tax package, experts said. At the same time that it passed the carbon tax, the Chilean government raised corporate taxes substantially, in a bid to increase revenues for education and other projects. As a result, the carbon tax raised less debate within Chile than it might have otherwise, though electricity companies have objected.

Sweden

Sweden enacted a tax on carbon emissions in 1991. Currently, the tax is $150/T CO2, but no tax is applied to fuels used for electricity generation, and industries are required to pay only 50% of the tax (Johansson 2000). However, non-industrial consumers pay a separate tax on electricity. Fuels from renewable sources such as ethanol, methane, biofuels, peat, and waste are exempted (Osborn). As a result the tax led to heavy expansion of the use of biomass for heating and industry. The Swedish Ministry of Environment forecasted in 1997 that by 2000 the tax policy would have reduced CO2emissions in 2000 by 20 to 25% more than a conventional, regulatory-based policy package (Johansson 2000). On September 17, 2007, Sweden’s government announced that it will increase its carbon taxes to address climate change. Petrol prices will go up 17 öre per litre, with the increase in fuel tax calculated on the basis of a 6 öre tax increase per kilo of CO2 emitted. (The Local)

A new (July 2014) major report by the International Monetary Fund, “Getting Energy Prices Right,” briefly summarized Sweden’s carbon-fuels tax regime as follows:

In the early 1990s, Sweden introduced taxes on oil and natural gas to charge for carbon and (for oil) sulfur dioxide and on coal-related sulfur dioxide and industrial nitrogen oxide emissions. These reforms were part of a broader tax-shifting operation that also strengthened the value-added taxes while reducing taxes on labor and traditional energy taxes (on motor fuels and other oil products). (See Box 3.5, “Environmental Tax Shifting in Practice,” p. 41. The full report is behind a paywall and may be ordered via this link; Chapter 1 of the report, a summary, may be downloaded at no charge via this link.)

Sweden’s carbon tax history and current status were summarized intelligently in a 2013 blog post by “realmelo,” who appears to be a graduate student in economics in British Columbia. Click here for her/his useful, brief report.

Other Nations

(Note: See comment at bottom of page on the Vermont University Law School book, The Reality Of Carbon Taxes In The 21st Century.)

France has no carbon price outside of the implicit price from its participation in the European Union’s Emission Trading System. In April 2016, however, Ségolène Royal, Minister of Environment, Energy and the Sea, issued a four-page declaration calling for the nations of Europe to adopt “a carbon component in the energy tax” of €22/tonne in 2016, with a price trajectory of €56/tonne in 2020 and €100/tonne in 2030. Converting from euros (at the 1.14 exchange rate of 4-April-2016) and metric tons, the price schedule equates to $23/ton today, $58/ton in 2020 and $103/ton in 2030. She wrote:

This measure is essential to encourage energy efficiency and the development of renewable energy in the transport and construction sectors, which have the largest potential for investment and job creation. This change can be made by revising directive 2003/96/CE restructuring the communal taxation framework for energy products and electricity, which has remained unchanged for several years. It may also be undertaken by Member States individually. It should also be based on the principle of fiscal neutrality to avoid increasing mandatory contributions and instead favour the transfer of taxation to fossil fuels. The context is favourable because the drop in the price of hydrocarbons and gas is significant enough so that the carbon component will not result in increasing the final bill including all taxes for consumers (including motorists). Thus, the introduction of the carbon component preserves purchasing power over the short term, but gives a clear signal of the need to quickly carry out energy retrofitting on housing, purchase clean vehicles and develop renewable energy (especially renewable heat and biogas).

Minister Royal’s statement also urged EU member states to “work for the establishment of the carbon price outside the European Union and unite countries that choose to act.”

The goal is not to impose a single worldwide price or a world CO2 market, but to bring together all committed countries and companies around common principles: ensure the carbon price is within the range of between $10-20/tonne before 2020 and $30-80/tonne in 2030; remove subsidies for fossil fuels; prepare for price convergence through networked carbon markets or mechanisms for rebalancing competition such as carbon inclusion mechanisms. The alliance may rely on the Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition, on condition that it follows its road map and expands it to new countries.

Finland enacted a carbon tax in 1990, the first country to do so. While originally based only on carbon content, it was subsequently changed to a combination carbon/energy tax (U.S. EPA National Center for Environmental Economics). The current tax is €18.05 per tonne of CO2 (€66.2 per tonne of carbon) or $24.39 per tonne of CO2 ($89.39 per tonne of carbon) in U.S. dollars (using the August 17, 2007 exchange rate of USD 1.00= Euro 0.7405). Current taxes are summarized in a Ministry of the Environment fact sheet Environmentally Related Energy Taxation in Finland.

New Zealand made plans in 2005 to enact a carbon tax equivalent to $10.67 (of U.S.) per ton of carbon (based on conversion rate of USD 1.00 = NZD 0.71). The tax would have been revenue-neutral, with proceeds used to reduce other taxes (Hodgson 2005). However, a new government determined that the carbon tax would not cut emissions enough to justify the costs, and the tax was abandoned (Myer 2005). [CTC addendum: In Sept. 2007 the government unveiled a proposed emissions cap-and-trade scheme intended to cover all carbon emissions. The NZ Green Party’s preliminary assessment provides some details.]

Archived Supporters

This page is a catch-all repository of expressions of support for carbon taxes or other forms of carbon pricing by individuals who no longer occupy the positions of influence (as office-holders, editorial columnists, etc.) that they held at the time those statements appeared. For more current expressions, go to the individual pages (Public officials, Economists, Scientists, and so-forth) listed in the pull-down menu under Supporters.)

Public Officials

Former Energy Secretary Stephen Chu

In a February 2009 New York Times interview, Secretary Chu said “that while President Obama and Congressional Democratic leaders had endorsed a so-called cap-and-trade system to control global warming pollutants, there were alternatives that could emerge, including a tax on carbon emissions or a modified version of cap-and-trade.” Chu was one of four Nobel prize winners (he was awarded the Physics prize in 1997) to sign CTC’s Paris letter calling upon the UN climate negotiators to endorse national and global carbon taxes.

Paul Volcker, chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, 1979-1987

Volcker, who died in 2019, was revered in the business and financial community for shepherding the U.S. economy out of the “stagflation” of the 1970s into the long-term boom of the 1980s and beyond, as chairman of the Federal Reserve under Presidents Carter and Reagan (1979-87). Speaking to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Egypt, earlier this year, he stated: “[The argument that taxes on oil or carbon emissions would ruin an economy is] fundamentally false. First of all, I don’t think [such a step] is going to have that much of an impact on the economy overall. Second of all, if you don’t do it, you can be sure that the economy will go down the drain in the next 30 years,” Volcker said. Referring to the new report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Volcker added:

What may happen to the dollar, and what may happen to growth in China or whatever pale into insignificance compared with the question of what happens to this planet over the next 30 or 40 years if no action is taken… The scientists seem pretty well agreed that [global warming] is still potentially manageable if we act decisively, beginning now into the next decade or so, by taking measures that are technically and economically feasible.

(All quotes attributed to Mr. Volcker, above, are from an article published in the International Herald Tribune on Feb. 6, 2007, US: Economist Paul Volcker Says Steps to Curb Global Warming Would Not Devastate an Economy.)

Senator Bill Nelson (D-FL, 2001-2019)

Pope Francis’ June 2015 encyclical, calling for urgent action to equitably respond to the dangers of global warming and urging policies requiring polluters to pay for climate damage, prompted Senator Bill Nelson to speak out on the Senate floor. Nelson explained the need for a carbon tax whose revenue could be used to reduce other taxes that impede economic growth. (Video.)

Senator Christopher Dodd (D-CT, 1981-2011)

Dodd anchored his 2007 presidential candidacy to a Corporate Carbon Tax. As he explained: “Until you deal with the issue of price, until you impose a corporate carbon tax, we will never get away from fossil fuels. It’s the only way this can be achieved. You have to advocate that if you’re serious about global warming.” (NY Times, 7/24/07.)

Bill Bradley (D-NJ, 1979-1997)

From Bradley’s op-ed, We Can Get Out of These Ruts, in the April 1, 2007 Washington Post (written a decade after he left the Senate):

We also need to change our tax system to reduce our oil dependence. In general, we ought to reduce taxes on things we need, such as wages, and raise taxes on whatever is dangerous to us, such as pollution and resource depletion. We could implement a $1 per gallon gasoline tax; or an equivalent carbon tax … After a few years of adjustment in the case of a gasoline or carbon tax, cars would be more fuel-efficient, so consumers would pay what they used to pay for the same amount of driving, and the broad middle class would continue to pay lower employment taxes. The result would be increasing demand for goods and services; shrinking dependency payments such as unemployment compensation and welfare; lowered social costs, such as crime and avoidable illness; and a more equitable tax system that encourages rising employment.

Congressman John Delaney (D-MD, 2013-2019)

On Earth Day 2015, Rep. John Delaney introduced a discussion draft of his “Tax Pollution, Not Profits Act” that would establish a tax of $30 per metric ton of carbon dioxide or carbon dioxide equivalent, increasing each subsequent year at 4% above the rate of general inflation. Delaney’s proposal would apply revenues to reduce the corporate tax rate to 28%, provide monthly payments to low-income and middle-class households, and fund job training, early retirement and health care benefits to coal workers.

Congressman Henry Waxman (D-CA, 1975-2015)

Waxman, ranking member of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and co-author of the the American Clean Energy and Security Act, a cap-and-trade measure that passed the House in 2009 but failed in the Senate, began seeking public input on a proposal for a much simpler carbon tax in early 2013. With Republicans (many of whom are climate science denialists) wielding the gavel in the House, Waxman’s initiative made little headway. Nevertheless, Waxman’s shift appeared to bode well for efforts to enact simple, transparent carbon taxes without the gimmicks of complex cap, trade and offset schemes.

Congressman Bob Inglis (R-SC, 1993-1999, 2005-2011)

Inglis represented South Carolina’s 4th Congressional District for six terms before losing the 2010 Republican primary to a Tea-Party backed rival. With economist Arthur Laffer, Inglis published An Emissions Plan Conservatives Could Warm To (NY Times, 12/08), calling on Congress to enact a revenue-neutral U.S. carbon tax (emphasis added):

Conservatives don’t support tax increases that are veiled as “cap and trade” schemes for pollution permits. But offer us a tax swap, and we could become the new administration’s best allies on climate change.

A climate-change bill withered in Congress this summer because families don’t need an enormous, and hidden, tax increase. If the bill’s authors had instead proposed a simple carbon tax coupled with an equal, offsetting reduction in income taxes or payroll taxes, a dynamic new energy security policy could have taken root.

As long as national security risks aren’t factored into the cost of gasoline and as long as carbon dioxide can be emitted without penalty, oil will continue to have an advantage over emerging fuels in the marketplace, and we’ll continue our ruinous addiction to it. We need to impose a tax on the thing we want less of (carbon dioxide) and reduce taxes on the things we want more of (income and jobs). A carbon tax would attach the national security and environmental costs to carbon-based fuels like oil, causing the market to recognize the price of these negative externalities.

Conservatives do not have to agree that humans are causing climate change to recognize a sensible energy solution. All we need to assume is that burning less fossil fuels would be a good thing. Based on the current scientific consensus and the potential environmental benefits, it’s prudent to do what we can to reduce global carbon emissions. When you add the national security concerns, reducing our reliance on fossil fuels becomes a no-brainer.

It is essential … that any taxes on carbon emissions be accompanied by equal, pro-growth tax cuts. A carbon tax that isn’t accompanied by a reduction in other taxes is a nonstarter. Fiscal conservatives would gladly trade a carbon tax for a reduction in payroll or income taxes, but we can’t go along with an overall tax increase.

The good news is that both Democrats and Republicans could support a carbon tax offset by a payroll or income tax cut.

Two carbon tax bills introduced in House Ways & Means (tax-writing committee) embodied much of what Rep. Inglis advocated in his op-ed: Stark-McDermott, filed in April 2007, and Larson, filed in August. (More details on our Bills page.) Rep. Inglis now chairs republicEn, (formerly the Energy & Enterprise Initiative at George Mason University) and is a vocal advocate for a revenue-neutral U.S.carbon tax.

Congressman Pete Stark (D-CA, 1973-2013) and Congressman Jim McDermott (D-WA, 1989-2017)

(Former) Congressmen Stark, who died in 2020, and McDermott were lead sponsors of the “Save Our Climate Act,” (2007) that would have imposed a $10 per ton (of carbon) charge on coal, petroleum and natural gas when the fuel is either extracted or imported. The charge would increase by $10 every year until U.S. carbon dioxide emissions have dropped 80% from 1990 levels. Introducing the bill, Congressman Stark eloquently stated:

The question is not if human activity is responsible for global climate change, but how the United States will respond,” said Stark. “Predictable, transparent and universal, a carbon tax is a simple solution to a difficult problem. It would drastically reduce our carbon dioxide emissions by providing an economic disincentive for the use of carbon-based fossil fuels and an incentive for the development and use of cleaner alternative energies. The Save Our Climate Act would establish the United States as a global leader in environmental protection and encourage other nations – most of whom have already acknowledged the climate change threat – to take similar action to reduce emissions. I strongly encourage Congress to pass a carbon tax.

CTC reported on the Stark-McDermott bill here.

Editorial Positions

The New York Times

See our Editorial Positions page for more recent expressions.

Global Warming and Your Wallet (July 6, 2007): “When the market, on its own, fails to arrive at the proper price for goods and services, it’s the job of government to correct the failure… We are now using the atmosphere as a free dumping ground for carbon emissions. Unless we — industry and consumers — are made to pay a significant price for doing so, we will never get anywhere.”

Warming Up on Capitol Hill (March 25, 2007): “Forcing polluters to, in effect, pay a fee for every ton of carbon dioxide they emit will create powerful incentives for developing and deploying cleaner technologies.”

The Truth About Coal (Feb. 25, 2007): “There is a need to put a price on carbon to force companies to abandon older, dirtier technologies for newer, cleaner ones. Right now, everyone is using the atmosphere like a municipal dump, depositing carbon dioxide free. Start charging for the privilege and people will find smarter ways to do business. A carbon tax is one approach. Another is to impose a steadily decreasing cap on emissions and let individual companies figure out ways to stay below the cap.”

Avoiding Calamity on the Cheap (Nov. 3, 2006): “Since the dawn of the industrial revolution, the atmosphere has served as a free dumping ground for carbon gases. If people and industries are made to pay heavily for the privilege, they will inevitably be driven to develop cleaner fuels, cars and factories.”

The Washington Post

See our Editorial Positions page for more recent expressions.

Some Positive Energy — Now Start Talking About a Carbon Tax, (June 25, 2007).

As important as many of the measures in [the Senate energy] bill are, they amount to only tinkering at the margins of a serious problem. What the Senate bill doesn’t do — and what the House bill won’t do when it is brought to the floor for consideration next month — is spark a necessary debate on the imposition of a cap-and-trade system or a carbon tax. This must be on the agenda after the Fourth of July recess when the Senate is expected to take up global warming. Sooner or later, Congress will have to realize that slapping a price on carbon emissions and then getting out of the way to let the market decide how best to deal with it is the wisest course of action.

Sorry Record – Waiting for breakthrough technologies is not the way to reduce greenhouse gases (July 11, 2006)

[The Administration] has resisted taxing carbon use, preferring instead to provide incentives for oil and gas extraction — just the opposite of what’s needed.

Los Angeles Times

See our Editorial Positions page for more recent expressions.

The L.A. Times ran two stirring editorials in May-June 2007 that powerfully made the case for taxing carbon. Here are excerpts:

Time to Tax Carbon, (May 28, 2007):

There is a growing consensus among economists around the world that a carbon tax is the best way to combat global warming, and there are prominent backers across the political spectrum … Yet the political consensus is going in a very different direction. European leaders are pushing hard for the United States and other countries to join their failed carbon-trading scheme, and there are no fewer than five bills before Congress that would impose a federal cap-and-trade system. On the other side, there is just one lonely bill in the House, from Rep. Pete Stark (D-Fremont), to impose a carbon tax, and it’s not expected to go far.

The obvious reason is that, for voters, taxes are radioactive, while carbon trading sounds like something that just affects utilities and big corporations. The many green politicians stumping for cap-and-trade seldom point out that such a system would result in higher and less predictable power bills. Ironically, even though a carbon tax could cost voters less, cap-and-trade is being sold as the more consumer-friendly approach.

A well-designed, well-monitored carbon-trading scheme could deeply reduce greenhouse gases with less economic damage than pure regulation. But it’s not the best way, and it is so complex that it would probably take many years to iron out all the wrinkles. Voters might well embrace carbon taxes if political leaders were more honest about the comparative costs.

Reinveting Kyoto, (June 11, 2007):

A better treaty [than Kyoto] would scrap the unworkable carbon-trading scheme and instead impose new taxes on carbon-based fuels. As recently explained in the first installment of this series [Time to Tax Carbon, above], carbon taxes avoid many of the pitfalls of carbon trading. They would produce an equal incentive for every nation to clean up without relying on arbitrary dates or caps, or transferring money from one nation to another. They’re also much less subject to corruption because they give governments an incentive to monitor and crack down on polluters (the tax money goes to the government, so the government wins by keeping polluters honest)… Real solutions to global warming, such as carbon taxes, won’t come cheap — they’ll make power bills steeper and gas prices even higher than they are now. But the economic news isn’t all bad. Much of the clean technology of the future will probably be developed in the United States and sold overseas. Think of [a carbon tax] as a novel way of reducing our trade deficit with China while building a cleaner world.“

For the strong critique of cap-and-trade in the Time to Tax Carbon editorial, click here.

Other Newspapers

Detroit Free Press: