Predictable Rising Carbon Tax Beats Hidden, Volatile Cap & Trade (WaPo LTE)

Search Results for: cap and trade

Carbon Tax on Trial: Chimera or Green Charm?

Just before Thanksgiving, Grist political blogger David Roberts posted a sharp challenge to carbon-tax advocates, contending that we were, in effect, ascribing “magical” properties to carbon taxes. Roberts spelled out 10 drawbacks to carbon taxes, with this bottom line: any carbon tax legislation that could make it through Congress would likely be feeble and regressive, and perhaps even counter-productive.

David is arguably the green community’s most prolific and astute blogger, particularly on environmental politics. His qualms about pushing for a U.S. carbon tax deserve to be taken seriously. We’ve reproduced his Grist post, below. Alongside it is our point-by-point response. Let us know what you think.

— Charles Komanoff & James Handley

10 reasons a carbon tax is trickier than you thinkBy David Roberts, Grist House GOP leaders recently confirmed again what I wrote last week: There isn’t going to be a carbon tax in the next two years or, probably, for as long as the GOP controls the House. I’ve been asked by a few climate types, “Why not spend your time pushing for it rather than poo-pooing its chances?” It’s a reasonable question. The answer, I suppose, is that I do not regard it with the same reverence as many economists and climate hawks. That’s not to say I wouldn’t welcome a substantial, well-designed carbon tax. But is it the sine qua non of climate policy, the standard against which all climate solutions are measured and for which any sacrifice is justified? No. Those who support a carbon tax over cap-and-trade often tout its simplicity, but the fact is, there are plenty of ways to screw up a climate tax too. Not everything that goes under the name is worthy of support, especially if it’s achieved at the expense of other liberal or green priorities. And given the current political milieu, it’s likely that any carbon tax that did manage to pass would be a bum deal for America’s poor and middle class. (Actually, that’s probably true for anything that passes, period.) Here are 10 reasons for a more tempered and realistic attitude toward a carbon tax. |

To save climate, no other policy tool comes close to a carbon taxBy Charles Komanoff & James Handley, Carbon Tax Center Thank you for elucidating your reservations about placing a carbon tax at the heart of U.S. climate policy. Until now, your many Grist posts critiquing carbon taxes have focused on political infeasibility. Now you’ve presented your policy objections. Thanks for bringing your concerns out into the open. No surprise: the Carbon Tax Center indeed views a U.S. carbon tax as the sine qua non of effective climate policy — provided it builds toward a substantial price that rises steadily and predictably over time. With a ramped-up tax, the initial carbon charge can be modest, giving businesses and families time to adapt, while still broadcasting a clear price signal to begin shifting millions of decisions toward less energy and emissions — big decisions that determine design of vehicles and transport and that set the pace and nature of investment in low- and non-carbon energy; as well as the full gamut of household-level decisions, many of which can’t and won’t be touched without a carbon tax. Almost as importantly, a robust carbon tax changes the culture by broadening the definition of pollution and valorizing conserving behaviors with monetary rewards. Here are our counterpoints to David’s 10 points. |

| 1. It’s conservative.

There’s a reason so many conservative (and neoliberal) economists support carbon taxes: They fit comfortably in a worldview that says problems are most effectively solved by markets, with minimal government intervention.Current markets have a flaw: They do not reflect the external costs associated with carbon dioxide emissions (namely, the impacts of a heating planet). The answer, economists argue, is to determine the “social cost of carbon” and to integrate that cost into markets via a carbon price, tax, or fee. With an economy-wide, technology-agnostic carbon tax in place, the market will eliminate carbon wherever it is cheapest to do so, insuring that we don’t “overpay” for carbon reductions. Implicit (and often explicit) in this view is the notion that other attempts to tackle carbon — say, EPA power plant rules, or fuel-economy standards, or clean-energy tax credits — are merely backdoor, inefficient ways of pricing carbon. If you get the social cost of carbon right and levy an economy-wide tax that prices all tons of carbon equally, then you have optimized the market, carbon-wise. All other regulations and subsidies will only serve to disrupt market efficiency. They are sand in the gears, as it were. The problems with this worldview are too many to list here, much less to litigate. Economists James Galbraith and Dean Baker argue that free markets are a myth; all markets everywhere are already designed, shaped, and regulated, usually to the benefit of the wealthy. Economist Dani Rodrick argues that industrial policy — “picking winners and losers” — is ubiquitous, a feature of all advanced economies, whether acknowledged or not. Sociologist Fred Block argues that virtually every industrial success story (e.g., fracking) can be traced to government-supported innovation. Anyone familiar with the U.S. electricity sector knows that there is little resembling a market in that Rube Goldberg hodgepodge of overlapping jurisdictions and quasi-monopolies. The entire U.S. coal sector depends on supply from the Powder River basin, which is public land administered by the government. Internal-combustion vehicles are heavily favored by a century of road-building and sprawling land use. And so on. There is no pristine “free market” for regulations and subsidies to besmirch. The game is always rigged, and right now it’s rigged in favor of the fossil-fueled status quo. The notion that a problem like climate change, with its century-spanning effects and potentially existential risks, will be solved exclusively or even primarily with “market mechanisms” is a religious doctrine, not a realistic appraisal. What government proactively plans, encourages, and accomplishes is just as important to the climate struggle as what the market penalizes. Put more bluntly: the spending matters as much as the taxing. Which implies that … |

1. A carbon tax is conservative and progressive.

We don’t think of a carbon tax as a market mechanism; there’s no need to create a new market. It’s a price mechanism. Call it a market corrective if you wish, but the term “market” is both a misnomer and a turnoff for carbon tax adherents (actual and potential) who don’t identify with market ideology. A carbon tax would correct existing markets that systematically under-reward virtually every action, every device, every innovation that reduces fossil fuel use because the prices of those fuels omit the costs of climate damage (not to mention most of the other harms from mining and burning coal, oil and gas). We don’t accept your suggestion that economists and policy-makers need to “get the social cost of carbon right” in order to set a carbon tax. For one thing, no two economists will ever agree on that number. More importantly, every climate-aware person already lives with the knowledge that the social cost of carbon is enormous: the likely descent of human civilization into chaos in the face of wholesale climate disruption. Our job as advocates isn’t to fix the “right” price of carbon but to maximize the internalization of carbon’s societal costs into the prices of fossil fuels. (Could any politically viable carbon tax capture the entire social cost?) And we emphatically reject the insinuation that we’re beholden to a purist belief that complementary measures to control and reduce carbon are irrelevant or harmful. Like you, we’re painfully aware of the multitude of ways in which market barriers like split incentives, inadequate information and path-dependence impede innovation and buy-in for energy efficiency and renewables. Therefore, like you, we strongly support regulatory standards, especially those that address inefficiency in product and building design. Still, let’s be realistic about their limits:

As you note, David, there is no pristine “free market” in energy or anything else. But so what? By itself a carbon tax won’t level the playing field, but it will lower the tilt. And as the tax rises, the tilt will diminish, allowing clean energy and a conservation ethic to compete with dirty energy and an ethic of waste. |

| 2. It’s the revenue, stupid.

Brookings notes that …… a carbon tax starting at $20 per ton and rising at 4 percent annually per year in real terms would raise on average $150 billion a year over a 10-year period while reducing carbon dioxide emissions 14 percent below 2006 levels by 2020 and 20 percent below 2006 levels by 2050.$150 billion a year — pretty soon you’re talking about real money! That could be used to support cleantech R&D or deploy renewable energy or build green infrastructure … or it could be used for none of those. Point is, what happens to the revenue should be at the center of climate hawks’ negotiating strategy; it’s not some peripheral bargaining chip. |

2. “Revenue recycle” will help the tax to rise.

We think you’ve got the revenue matter backwards. Revenue treatment is important, of course, as befits any new tax that puts hundreds of billions a year in play. But rather than fund cleantech R&D and green infrastructure, we need to direct the revenue to support productive economic activity and offset the hit to poor and middle-income families’ disposable incomes. Doing so will help win the political buy-in to legislate periodic renewal of the annual rises in the tax that will drive the needed changes in behavior, infrastructure and R&D far better than subsidies. This is why we frame carbon tax revenue treatment in macro-economic rather than energy-policy terms. (We say more about this at #3, next.) |

| 3. “Revenue-neutral” means foregoing any money for climate solutions.

A “revenue neutral” carbon tax is one in which all of the revenue raised is returned automatically to taxpayers. Most of the carbon tax proposals floating around today are revenue neutral, mainly, as far as I can tell, because conservatives demand it. (Conservatives don’t trust government with revenue.) There are three ways to achieve revenue neutrality, which I will list from most to least desirable:

Note what all these uses of carbon revenue have in common: They do nothing to reduce carbon emissions or encourage clean energy. And to boot, they wouldn’t even reduce taxes much. |

3. “Revenue-neutral” helps keep the carbon tax rising.

Like many carbon tax advocates, though not all, we (Charles & James) personally have progressive perspectives. Outside the Carbon Tax Center we advocate for robust government investment in education, public transportation, health protection, housing, and a broad spectrum of social services and support nets. Yet we ardently want carbon taxes to be close to 100% revenue-neutral (with minor and transitory exceptions for assistance for displaced workers and communities), for two reasons: First, as you have detailed in many posts over the years, it’s next to impossible politically to direct carbon tax revenues to “good things” (e.g., green tech, mass transit) without also opening the floodgates for bads like “clean” coal, next-generation reactor loan guarantees, and biofuel boondoggles. Better to hold the line and continue to fund R&D from established pots of money. Second, the carbon tax is going to have to rise steeply and steadily over a long time period to provide strong, ongoing incentives to phase out and finish off fossil fuels. Returning essentially all of the revenues to American households — whether through reductions in taxes like payroll taxes that discourage hiring and are distributionally regressive, or monthly electronic ”dividends,” or a combination — is essential to winning support for the rising carbon tax. Indeed, we want Americans to find these revenue return mechanisms so appealing that they will welcome ongoing rises in the carbon tax level so as to expand their size (and, ultimately, sustain them in the face of the declining carbon tax base as fossil fuel use dwindles, as we discuss in #6, below). |

| 4. Carbon money should fund clean energy.

There are two distinct tasks for climate policy. One is to reduce carbon emissions at lowest cost. The other is to develop and deploy a new energy system. The evidence shows that a carbon tax is good at the first, but not great at the second. That’s where the revenue comes in.I was going to gather together the research on this, but then I discovered that Mark Muro of Brookings has done it for me. Bless you, Mark Muro of Brookings. (Pardon the long excerpt — all the emphases are mine.) [Ed. note: We’ve put the long Muro excerpt in italics. — Komanoff] “The sticking point here is that while the conventional wisdom among carbon pricers holds that higher dirty energy prices will provide the right market signals to entrepreneurs, who will then develop and deploy clean new technologies, a ton of evidence suggests that pricing alone won’t generate enough deployment to get us where we need to go. Instead, it is becoming increasingly obvious that along with pricing we need a direct technology deployment push. “One hint of this comes from the modelers. Under neither of their respective carbon tax proposals do the Brookings or MIT groups forecast that emissions will drop enough to even come close to the 80 percent cut in emissions below 1990 levels that is the nation’s long-term carbon emissions goal. Yes, fossil fuel use would go down, oil imports would shrink slightly, and emissions would decline, but much more work would need to be done to tackle global warming. Similarly, an interesting analysis by the Breakthrough Institute concluded that a $20 per ton carbon tax would offer just one-half to one-fifth the incentive of today’s subsidies for the deployment of solar, wind, and other zero-carbon technologies. “These results reflect the growing body of literature that has begun to suggest—and document—that broad economy-wide pricing strategies alone induce only modest technology change and deployment. Last year, Matt Hourihan and Rob Atkinson of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation ran through some of the literature pertaining to a wide range of industries, while at the same time, scholarship specifically on energy has been accumulating. “Ackerman argued a few years ago that getting the price right is necessary but far from sufficient to mitigate climate change and that direct public sector initiatives are required to disrupt path-dependencies and accelerate learning. Acemoglu and others more recently demonstrated that the optimal carbon policy is not one-sided but involves both carbon taxes and direct research subsidies. They urge immediate action. “Turning to empirical evidence, Calel and Dechezleprêtre looked at company patenting patterns under the EU emissions trading system (a cap-and-trade pricing scheme) and concluded that the system has had very little impact on low-carbon technology change. And then, earlier this year, a Swiss-German team found that the EU system has stimulated only limited adoption of low-emissions technology and that research, development, and deployment (RD&D) technology ‘push’ measures induced more action. This group concluded that none of the first three phases of the trading system were ‘capable of triggering increased non-emitting technology adoption’ and that ‘only renewable-technology pull policies had this effect.’ “And so we arrive back at the revenue: The accumulating evidence and the appropriate fit of the tax to its use argue heavily for at least a portion of the revenue of any carbon pollution fee to be applied to direct investment in energy system clean-up, whether through R&D or later-stage deployment supports.” In short, the tax side is not enough. Effective climate policy also requires spending. This is commensurate with some of the revenue being rebated to low-income taxpayers, or used to reduce taxes, or wasted on the fake long-term deficit problems. Public investment in clean energy is not the only legitimate use of the revenue. But it is the use for which climate hawks should be advocating most strongly. |

4. A strong enough carbon tax will indeed drive investment to clean energy.

We don’t dispute Mark Muro’s assertion in his “Carbon Tax Dreams” post that we’ll never usher in massive cleantech investment or otherwise shrink fossil fuel use and carbon emissions to near zero with just the price signals from a carbon tax that starts at a mere $15 to $20/ton and rises only 4% a year faster than inflation. The Carbon Tax Center’s carbon tax spreadsheet model yields the same conclusion. So does a pocket calculator: assuming 3% annual inflation, a tax rising 4% a year faster than inflation would take a decade to double in nominal terms, and almost two decades to double in real terms. That’s way too slow a ramp-up, considering that a carbon price of $40/ton of CO2 would add a mere 36 cents to a gallon of gasoline and 1.5 cents/kWh to the average U.S. retail electricity price. We need a carbon tax that quickly gets to much higher rates than that. It doesn’t have to start like gangbusters; indeed, it shouldn’t, since families, businesses and institutions all need (and deserve) time to adapt to the new reality of higher fuel and energy prices. A steady and steep ramp-up rate is far more important and beneficial than a high starting point. These considerations make the ideal carbon tax close to that embodied in legislation introduced in 2009 by Representative John Larson (D-CT). Rep. Larson’s carbon tax starts at $15/ton and rises each year by $10-$15, with the actual increment depending on whether emissions are being driven down fast enough. In the tenth year of a carbon tax, the CO2 price would be between $100 and $145 per ton of CO2 under the Larson bill, vs. $28-$37 per ton for Muro’s scenarios. That 3-fold to 4-fold difference in the respective tenth-year carbon price would start to narrow eventually, though not until the start of the fourth decade, in absolute terms — indicating how fundamentally different the Larson tax scenario is from Mark Muro’s. The corollary, David, is that while your boldfaced assertions that “pricing alone won’t generate enough [clean-energy] deployment to get us where we need to go” and “broad economy-wide pricing strategies alone induce only modest technology change and deployment” may well hold for the undersized and only gradually rising tax levels you cited in your post, they don’t necessarily apply to the kind of robust tax presented in Rep. Larson’s bill. We do take seriously Frank Ackerman’s caveat in the paper you cited, that “Price incentives alone cannot be relied on to spark the creation of new low-carbon technologies.” But recall that Ackerman, writing in 2008, was in part responding to an IMF report published earlier that year whose year-2100 climate “targets” could have come from the Koch Brothers playbook: a CO2 concentration of 550 ppm, annual declines in emissions of only 0.6% till then, and a carbon tax starting at around $1/ton of CO2 and rising by just 67 cents a year. We suspect Dr. Ackerman might have a more sanguine view of the “market pull” of a carbon tax whose rate, like Rep. Larson’s, is a full order of magnitude greater than what the IMF envisioned. Our bottom line, then, is that we don’t believe that a small carbon tax used for subsidies and/or RD&D would provide anything close to the sustained broad market pull toward innovation that is required to address the climate crisis, and that could result from a substantial and briskly rising carbon tax. In our view, starting with as close to 100% revenue return as possible is the best way to build growing political will for a robust and effective carbon tax, i.e., one with sustained, predictable and sizeable increases from each year to the next. There, the market pull (including long-term price expectations) should suffice to elicit clean-tech innovation and revolution. In that case, however, “revenue return” is mandatory — ethically, to offset households’ higher energy costs, and politically, to forge and maintain the constituency to keep the tax level rising. |

| 5. Carbon taxes are regressive.

I mentioned this is passing already, but it’s worth emphasizing. On their own, carbon taxes hit the poor harder because the poor spend a larger proportion of their income on energy. It isn’t difficult to solve that problem. Using the revenue to reduce payroll taxes would do it. Setting aside some revenue for direct rebates to low-income taxpayers would do it. (By the way, the Waxman-Markey bill did exactly that.)But swapping a carbon tax for the income tax wouldn’t. Using carbon tax revenue to reduce the deficit wouldn’t. If climate hawks want progressivity — and they should, if they hope for broad grassroots support — they’ll have to fight for it. |

5. Tax regressivity is an anathema . . . but curable.

No argument here, David, though we spin this issue a bit differently. We agree that (i) putting revenue use aside, a carbon tax has a greater proportional impact as household income declines, and (ii) progressive revenue treatment such as a revenue swap on payroll taxes, or pro rata dividends, or low-income support, can mitigate and eliminate the regressivity. The Carbon Tax Center insists on such progressive treatment, though we concede that a final bill may be less than scrupulous on this score. (We also question the extent to which Waxman-Markey would have solved this problem, but we’ll save that discussion for another time.) |

| 6. Carbon tax revenue is supposed to decline.

Remember, the goal of a carbon tax is to decarbonize the economy. As carbon declines, carbon tax revenues will decline, unless the tax is almost continuously ramped up. This wouldn’t matter so much for revenue earmarked for clean energy or direct rebates. There will be less need for that revenue as the economy decarbonizes. But what if carbon taxes have replaced payroll taxes, which fund Social Security? As revenue declines, so will funding for Social Security. Not good. Or what if carbon taxes have replaced income taxes? As revenue declines, individual tax burdens will decline, which will delight conservatives, but should be a source of concern for liberals in favor of active government. The fact that a carbon tax is intended to phase itself out over time cannot have escaped the attention of its conservative supporters. |

6. The eventual decline in revenue is a non-problem.

“The fact that a carbon tax is intended to phase itself out over time,” as you put it well, David, belongs in the class of problems that at this juncture should matter only to extreme policy wonks. The Larson Bill, which we discussed under Point #4 above, and which certainly falls on the “aggressive” end of the carbon tax rate spectrum of, doesn’t reach max revenue until Year 18, when the annual intake is projected to plateau at just under $800 billion. (Note: that figure, which is drawn from our modeling of the Larson bill assuming annual rises of $12.50/ton, may change with revisions to the model now underway.) Long before then, there should be ongoing discussions about how to replace that revenue stream as it slowly and predictably shrinks. Indeed, given the amounts in question, we would expect those discussions to be a central feature of public policy in future decades. |

| 7. The carbon lobby will want to axe EPA regulations in exchange.

Exxon has been supporting a carbon tax (notionally) for several years, but it’s made clear that it sees such a tax as “an alternative to costly regulation.” This is what everyone’s favorite dirty-energy lobbyist Frank Maisano recently wrote (behind a paywall):No carbon tax should be considered before serious regulatory reform is undertaken. The U.S. EPA is moving forward on an approach that regulates carbon, which is akin to fitting a square peg in a round hole. Not only is it legally dubious, but it is not likely not work in practice, either. Suffice to say, the fossil fuel lobby would never give a carbon tax their OK unless EPA regulations on carbon (and possibly other pollution regs) were scrapped. We saw this fight play out once already, around the cap-and-trade bill. Unless it was for a high-and-rising tax (which is unlikely), that would be a terrible trade for greens. The implicit carbon price in EPA regs is higher than an explicit tax would likely be. In developing regulations, EPA uses the government’s official “social cost of carbon,” which is around $26/ton. There’s good reason to think that figure is dramatically too low. But it is already higher than a politically realistic carbon tax. |

7. EPA regulation of climate pollution may not measure up to its regulation of public-health pollution.

This issue should be straightforward. Greens should hold the line on health-and-safety rules pertaining to the energy sector — emission limits governing pollutants like NOx and mercury (e.g., Mercury and Air Toxics Standards); mining and combustion waste (a/k/a Coal Combustion Residuals); fugitive emissions like methane; and “macro” regs like the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule. But prospective EPA rules directed at CO2 emissions may be another matter. Based on the authoritative 2011 paper by Burtraw et al. for Resources for the Future, new EPA regs will at best reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG’s) in 2020 by only 13% (vs. 2005). Further reductions would be harder to come by, given that “a regulatory approach is likely to lead to less innovation … than would occur under a flexible incentive-based program” such as a carbon tax. Moreover, unlike a carbon tax, GHG regulations would generate zero revenue. Symbols matter, and EPA authority on public-health pollution is vital. But EPA regulation of CO2 may be less valuable than you presume, David. (That EPA uses a $26/ton social cost of carbon in its analyses doesn’t mean that its regulations would bring the same reductions as would result from a $26/ton price.) |

| 8. The carbon lobby will want to axe clean-energy support programs in exchange.

The same argument goes for clean-energy subsidies: the implicit cost of carbon in those subsidies is far higher — two to five times higher — than a $20/ton carbon price. Trading subsidies for a tax would, especially in early years, represent far less direct support for clean energy. |

8. A robust carbon tax will do far more for clean energy than direct subsidies.

See #4, above, for our argument that a strongly rising carbon tax will drive investment to clean energy. In the limited space available here, we add that phasing out clean-energy subsidies would build political momentum to get rid of subsidies for fossil fuels and other forms of dirty energy. [Addendum: We nailed this issue in our Jan. 2014 formal comments to the Senate Finance Committee. Details, and link to those comments, are here. — Komanoff] |

| 9. The environmental benefits are uncertain.

The great benefit of a carbon cap over a carbon tax is that a cap ensures a particular level of emissions reductions (yes, yes, depending on how carbon offsets are used). The thing with a tax is, no one can be sure in advance how much it will reduce emissions. The history of environmental policy is one of overestimating costs, so chances are good that the initial tax level will be set conservatively. That’s what typically happens with cap-and-trade systems — compliance costs are overestimated, there are too many emission permits issued, permit prices plunge, and there’s little financial incentive to reduce emissions. But a cap-and-trade program has a built-in protective measure: the cap. Emissions are either falling or they aren’t, and if they aren’t, the cap provides a statutory basis for further action. It’s not perfect, but it’s something.What happens if a tax isn’t reducing emissions enough? It means Congress has to raise it. How much does Congress like raising taxes? How much do American voters like it when Congress raises taxes? Now imagine raising a tax repeatedly, on an ad hoc basis. Unless taxes take on a very different political valence in U.S. politics, that looks like a nightmare. The carbon tax could end up limping along at hopelessly low levels for ages, like the U.S. gasoline tax. Now, theoretically, the tax could be programmed to rise a certain percentage each year, like the one Brookings modeled. Or there could be a “look back” provision that periodically assesses the tax’s performance and adjusts it accordingly. But … |

9. Certainty in emission reductions is overrated.

That “no one can be sure in advance how much [a carbon tax] will reduce emissions” may well be the number one canard about carbon taxes. After all, what’s the use of knowing now how fast emissions will shrink, when we know that they have to shrink as fast as possible, which means faster than any carbon tax and/or other possible measures can deliver? The climate calamity is many orders of magnitude more dire and global than the acid rain problem. So can we please stop grafting the acid rain model onto climate? The declining sulfur cap in the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments was intelligently tailored to estimates by limnologists of Northeast U.S. lakes’ remaining capacity to withstand acid rain emissions. But we’ve already overshot the 350 ppm target for climate sustainability; atmospheric CO2 is at 390 ppm and rising. There’s no safe level for CO2 emissions now or in the foreseeable future. Any target ― 17% less by 2020, 40% less by 2030, 80% less by 2050 ― is no more than a talisman. What happens, you ask, if the carbon tax isn’t reducing emissions enough? In some proposals, the tax would rise automatically, in others Congress would have to raise it. But either way it’s crucial to structure revenue return so that a majority of Americans come out ahead and will back increases in the carbon tax rate. (See Points #2 and #3, above.) Built-in, recurring increases will not only obviate the need to return to Congress constantly; they will instill transformative price signals in America’s energy systems, infrastructure, land use and culture that, collectively, will move us from fossil fuels to clean energy. |

| 10. All political incentives push toward a poorly designed tax.

It’s true that a carbon tax can be well-designed. For economists, that means using the revenue to reduce distortionary taxes. For clean-energy hawks, it means using the revenue to spark cleantech growth. For both, it means provisions that automatically boost the tax if emission reductions are not on track. (And there are other considerations too: how far upstream to levy the tax, how to deal with cross-border “leakage,” etc. This post could have been even longer, trust me.) The worst possible thing to do from both perspectives would be to set the tax at a static, low level and use a bunch of the revenue to carve out special deals for various industries. Then you’d get the economic hit from the tax and malign distributional issues.And yet … that is exactly where all the incentives point. There are many financial interests involved. Every one of them will be leaning on legislators to a) keep the tax as low as possible and b) secure them favorable treatment. This same rent-seeking spectacle took place around the climate bill. But another benefit of a cap-and-trade system is that no matter how distributional issues are settled (i.e., no matter how the permits are allocated), the cap remains the same and the environmental benefits are guaranteed. When it comes to a tax, however, loopholes and kickbacks reduce environmental benefits. Securing those benefits will be a constant, running battle. Environmentalists will be “those people who are constantly fighting to raise taxes.” That is unlikely to endear them to the public or generate support for other green initiatives. To sum up A well-designed carbon tax would be a fantastic thing. In my dream world, it would start at $50/ton and rise 5 percent a year. Twenty-five percent of the revenue would go to rebates for low-income taxpayers; 25 percent would go to reducing payroll taxes; the rest would go to public investments in clean energy RD&D and infrastructure. Whee! Even a tax considerably smaller than that, done right, could enable Obama to meet the emission reduction goals he pledged in Copenhagen. It might also inspire other countries to follow suit, or at least convince other countries that the U.S. is finally in the climate game. It would be a big deal. But a carbon tax is not magic. If climate hawks go into negotiations accepting that carbon pricing must be revenue neutral, that market incentives can solve climate change on their own, that government spending and regulatory actions merely inhibit proper market functioning, that the overall tax burden needs to be reduced, that deficit reduction is an overriding short-term priority … well, even if they come out of that negotiation with a carbon tax (which, as noted earlier, they won’t), it will be low, regressive, and ineffective. And they will have worked themselves into an ideological corner that will be difficult to escape. Worse yet, what if they make all those concessions and come out of it with nothing? The concessions will remain on the record forever, serving as the baseline to future negotiations. (That’s pretty much how the cap-and-trade battle worked out.) What’s needed on climate change, ultimately, is a wholesale, society-wide commitment to remaking energy, agricultural, and land-use systems along low-carbon lines. “Market mechanisms” like a carbon tax are a crucial part of that effort, especially as a source of funding, but they are in no way a substitute for that effort. We won’t get out of this that easily. |

10. & Summation. Climate advocates’ job is to maximize political incentives for a robust carbon tax.

All political incentives push toward climate inaction, period, and not just toward a poorly designed carbon tax. We can either give up . . . or we can keep working to break the impasse — primarily by building support from below, but also by choosing policy strategically. Since giving up isn’t an option, let’s start by reviewing what we’ve established about carbon taxing thus far:

To these assertions, let’s add this:

Unlike revenue from selling tradeable emission permits, which would be subject to the extreme price volatility that has characterized every carbon cap-and-trade system, the revenue from a carbon tax is sufficiently predictable to serve as a building block for tax overhaul. (Lags in responding to the price signal make this particularly true in the tax’s initial years, which happen to be the most politically germane.) Earlier, under Point #4, we referenced the carbon tax proposed by Rep. John Larson, which our modeling suggests would reduce U.S. emissions by 30% within a decade while stimulating employment and economic activity. The Larson bill also includes border tax adjustments to protect domestic energy-intensive industries and to nudge U.S. trading partners to enact their own carbon taxes, leading to a global carbon price. The Larson bill could be said to be patterned on the British Columbia carbon tax, which went into effect in 2008 at a rate of roughly $9 per ton of CO2 and was incremented annually to its current (2012) level of approximately $27. On every criterion — climate, macro-economic, distributional, political — the tax appears thus far to be a resounding success. Consider:

To be sure, there are big differences between British Columbia and the 50 U.S. states, including hydro-rich BC’s effective exemption of electricity from its tax. Nevertheless, these lessons are ours for the taking: first, it may be better to square up to the political pain of raising the carbon price than to hide it; and second, a tax with transparent and ironclad revenue recycling can build the political appetite for raising the tax level to the point where deep carbon cuts actually take place. In sum: a carbon tax isn’t the whole answer, yet a transparent, briskly rising carbon tax will spur the development of many answers large and small that add up to a cultural transformation. Taxing carbon aligns everyone on the side of reducing emissions as fast and as far as possible. In reach, transparency and affordability, no other policy tool comes close. |

"Once the climate tipping point is past …"

Every so often, you read something that stops you in your tracks. That happened to me yesterday, when I came across this:

We are talking about our grandchildren living in a resource-constrained future where they have a chance to learn to live in balance with the planet, or our grandchildren living in a future truly filled with squalor, death and misery. Once the climate tipping point is past, human beings will pay any price to go back but it will be to no avail. And they will wonder why their ancestors thought driving SUVs and air conditioning the outdoors was more important than water, food and survival of their progeny.

I read this passage yesterday on Amtrak as I was returning to New York City from Washington. Last Saturday, I participated in one of the “Fossil Fuel Disaster Relief Rides” organized by the direct-action environmental group Time’s Up. We hauled supplies by bike to the Rockaways, one of dozens of districts in the New York region devastated by Hurricane Sandy, and we stuck around to help residents drag the sodden wreckage of their living rooms and garages onto the sidewalk. The scene was post-apocalyptic: trash mounds towering over twisted bungalows; dump trucks and ‘dozers lumbering down dirt-caked streets; dust, muck and ruin stretching for miles; the sun filtered through a torn sky. I also knew from published reports that my home town of Long Beach, on the next barrier beach to the east, had similarly been laid waste.

“Human beings will pay any price to go back but it will be to no avail.” Fittingly, the writer was responding to a post on Streetsblog, the blog of the “livable-streets” movement, that for some dubious reason was pouring cold water on the hope that a carbon tax might figure in the emerging equation for tax and fiscal reform. Not only that, the writer was telling other commenters that a visit to our (Carbon Tax Center) Web site could dispel their doubts that a carbon tax could be made effective and fair. Here’s her comment, in full:

Again, please see the link that Komanoff posted below in the very first comment. (www.carbontax.org) Most of the questions raised below are answered — how to measure carbon emissions, at what point in the emissions stream to effectively tax it, how a carbon tax can be revenue neutral, why no one is or will ever suggest taxing people breathing, etc.

As to how to deal with off-shoring of carbon emissions, we would indeed have to be more responsible about this than we have been with off-shoring all our other pollution. We could either refuse to trade with countries that don’t impose carbon taxes at similar levels, or we could levy a tariff on all imported products based on the level of that country’s gross fossil-fuel burning carbon emissions. (We would no doubt have to estimate in cases where self-reported numbers are unreliable.) This would have an added benefit of on-shoring manufacturing jobs back to the US.

With a carbon fee and dividend program, people would actually make money as long as they kept their usage below that of the average energy-squandering American. This is not difficult to do! All it takes it takes is simple behavioral changes and/or very small investments of money that will be paid back with lower fuel bills. But there simply must be a price signal or people will not change their energy consumption and carbon emissions patterns. And these carbon emission patterns need to drop immediately. Not by 2020 or 2030. Any plan that talks about doing something 2020 and beyond is a plan to do nothing because it will be too late. It is hypocritical greenwashing designed to distract and pretend, pure and simple.

We are talking about our grandchildren living in a resource-constrained future where they have a chance to learn to live in balance with the planet, or our grandchildren living in a future truly filled with squalor, death and misery. Once the climate tipping point is past, human beings will pay any price to go back but it will be to no avail. And they will wonder why their ancestors thought driving SUVs and air conditioning the outdoors was more important than water, food and survival of their progeny.

I don’t know if I’ve ever seen the case for a carbon tax made more powerfully and eloquently than in those four paragraphs. I know that I in lower Manhattan and my fellow New Yorkers in the Rockaways and Long Beach and Staten Island now wish we could have paid whatever it would have taken to buy the reduction in sea-level rise and ocean-temperature rise that might have quenched some of the force of Hurricane Sandy. Taking that knowledge and building it into support for a robust U.S. carbon tax is our new mission at the Carbon Tax Center.

PS: As for that Amtrak trip to DC yesterday. That’s where AEI, RFF, the IMF and Brookings held an all-day conference — before a packed house — on The Economics of Carbon Taxes. Click the link to unpack the acronyms and see the program. We’ll post a report soon.

When NY Gov. Cuomo 'Got' Climate Change

Superstorm Sandy has made climate change believers of many, but none better-known than New York Governor Andrew Cuomo. “[C]limate change is a reality, extreme weather is a reality, it is a reality that we are vulnerable,” Cuomo told New Yorkers at a post-Sandy briefing on Wed. Oct. 31, a day and a half after the tidal surge from the storm inundated coastal communities and spread unprecedented devastation across hundreds of miles of shoreline — and far inland as well — in Long Island, New York City and neighboring New Jersey. Lost to flooding, wind and even fire are more than 100 lives, uncounted homes — I’m guessing well over 100,000 — and entire villages and towns. State officials are estimating that damage to the region will exceed $50 billion, today’s NY Times reports, making it the country’s costliest storm other than Hurricane Katrina, which wiped out much of New Orleans in 2005.

Cuomo’s words, while unremarkable to anyone conversant with the basics of climate science, were unprecedentedly frank not just for him but for any major U.S. office-holder. They were also unscripted, suggesting that the governor may have had a “conversion moment” in which old perceptions gave way to a new reality. If so, I’ll bet the trigger came on the evening when Sandy struck. That would have been when Cuomo came face-to-face with the massive power of the floods unleashed by the storm.

Here’s how that moment was described by the weekly New York Observer, in its blow-by-blow account of how top city and state officials fought to comprehend the storm’s destructive force:

Joe Lhota (Metropolitan Transportation Authority chief): When I got downtown to meet [NYC Transit head Tom] Prendergast, we were looking at where we were, we both realized how deep the water was at South Ferry station. It didn’t surprise me when we found out later that the water was all way up to the ceiling. It was four feet above the ground that night. And then we walked over to the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, where we ran into the governor totally by accident. I don’t know why I went over to the Brooklyn-Battery tunnel. I really don’t. We hadn’t been told about water rushing in, but we went over there, and boy, what I saw was extraordinary. White-water rapids, and a pace — you could have created hydro power.

I’ll use the words that the governor used. It was disorienting. It was. You heard it. You saw it. And you weren’t really sure you were hearing it and seeing it correctly. I never expected the Hudson River to do that.

Josh Vlasto (Cuomo administration communications director and senior adviser): The governor was standing with Lhota at the mouth of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel and the water was rushing in so quickly that the sound was deafening. I think that for him, that was the moment — where the water was that night, when you’re down there, standing at the tunnel, there’s so much water that you can’t hear — I think the governor would say that was the “We Got a Problem” moment.

Howard Glaser (Cuomo administration director of state operations): It was a sound you never heard before in Lower Manhattan, a rushing river. And then we went over to the World Trade Center and we saw Niagara Falls was pouring into the site.

Those aren’t quotes from the governor, of course, but they may as well be, given how tightly he stage-manages his administration’s utterances and given that Lhota, Vlasto and Glaser all serve at his pleasure.

Nearly halfway through his (first) term, Gov. Cuomo is arguably the state’s most powerful governor since Rockefeller and its most popular chief since FDR. He is already the subject of considerable speculation as a possible Democratic presidential candidate for 2016. At the same time, energy issues concerning renewables, nuclear power and especially fracking are an increasing presence on his state policy and political plate. Like other concerns, political attention to climate change will ebb and flow depending on public pressure and the flow of events. But if the governor indeed had a climate-change conversion moment along the lines I’m suggesting, that moment might just spark policies — incentives, regulations, and perhaps even a state carbon fee — that could turn New York State into a leader in arresting the buildup of carbon pollution in the state’s — and planet’s — atmosphere.

Carbon-Tax Champion Pete Stark Loses House Seat

Tuesday’s election results were mostly positive for climate advocates. The defeats of far-right GOP Senate candidates Richard Mourdock (IN) and Todd Akin (MO) produced a twin blow to the anti-science Tea Party, while two of Congress’s most ardent carbon tax proponents, Rep. John Larson (D-CT) and Rep. Jim McDermott (D-WA), won handily. The re-election of President Obama over Republican Mitt Romney, aided by a dramatic last-minute embrace from superstorm Sandy-battered New Jersey Republican Governor Chris Christie, could also augur well for action on climate. So too could wins for a host of progressive state ballot initiatives, most notably California’s Proposition 30, which will generate $6 billion a year in new tax revenues to support public education.

There was this sour note for climate advocates, however: long-time California Congressmember Pete Stark lost his seat to a fellow Democrat, thanks to redistricting that cut off Stark from a majority of his former constituents, as well as the state’s new “top-two” primary system that pitted Stark against a centrist fellow Democrat rather than a GOP opponent. The victor, Eric Swalwell, an Alameda County prosecutor, is 31. Stark is 80, and has represented parts of California’s East Bay region since 1973, making him the dean of California’s Congressional delegation.

Rep. Stark was both an early and consistent leader in promoting a carbon tax in Congress. In April 2007, Stark introduced legislation that would have levied an upstream tax on fossil fuels equivalent to $10/ton of the fuel’s carbon content, rising annually by $10/ton until CO2 emissions had dropped by 80% from 1990 levels. The bill went nowhere, what with the then-majority House Democrats in the thrall of competing cap-and-trade legislation. But as the first submittal of carbon tax legislation to Congress, it helped galvanize carbon tax advocates, particularly at green groups not beholden to cap-and-trade, including the Carbon Tax Center. Last fall, Rep. Stark dusted off his 2007 bill, upped the tax level to $10 per ton of CO2 (a nearly 4-fold increase) and introduced it as the Save Our Climate Act of 2011.

Pete Stark has been outspoken on many fronts in addition to climate. He was a vocal opponent of the War in Iraq and a strong supporter of a single-payer health-care system. Perhaps even more remarkably, in 2007 Rep. Stark publicly declared his disbelief in a Supreme Being, making him the first openly-declared atheist to serve in Congress. The following year, Stark’s courage was honored with the Humanist of the Year award from the American Humanist Association.

America will be the poorer for losing Rep. Stark’s independence, critical thinking and passion for justice in Congress. The Carbon Tax Center will miss him for these qualities and his vision to place a steadily rising carbon tax at the center of climate protection. A fitting legacy would be enactment of legislation along the lines of Pete Stark’s Save Our Climate Act.

Addendum, Dec. 5, 2012: A profile of Eric Swalwell posted today in the New Republic touches on the missteps that made Rep. Stark politically vulnerable and contributed to his defeat.

Bloomberg No Stranger to Climate Advocacy — Especially for a Carbon Tax

New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s endorsement yesterday of President Obama’s re-election may have caught the political class by surprise, but not the Carbon Tax Center.

It was five years ago today, in Seattle, at a climate summit organized by the U.S. Conference of Mayors, that Bloomberg made a full-throated appeal to Congress to enact a carbon tax. His speech then, on Nov. 2, 2007, remains the most passionate and compelling call for truly effective climate action by any major American political figure.

The Carbon Tax Center’s New York headquarters are currently off the grid, due to Superstorm Sandy. We hope to be back around Election Day with fresh commentary, including discussion of whether the President’s first-term climate program and second-term outlook merited Bloomberg’s endorsement. For now, to show what real climate leadership looks like, please feast on the full text of Mayor Bloomberg’s 2007 speech, included here, courtesy of The New York Times. (The mayor’s extensive discussion of carbon taxing comes toward the end.)

— Charles Komanoff

Remarks by New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, in Seattle, Washington, Nov. 2, 2007, before the U.S. Conference of Mayors’ “Climate Protection Summit”

I’ve had the pleasure of working with Mayor Palmer, Mayor Nickels, Mayor Diaz — and many others in this room — through our coalition of Mayors Against Illegal Guns, which now includes more than 240 mayors from all around the country — Republicans, Democrats, and independents. If you haven’t joined yet, we’d love to have you — and I think illegal guns and climate change are two of the best examples of cities leading where Washington has not. On both issues, those in Washington prefer talk to action. On illegal guns, they extol the virtues of the Second Amendment, which is all well and good, but let’s get serious: protecting the Second Amendment does not stop you from keeping illegal guns out of the hands of criminals. It’s just a political duck-and-cover that allows legislators to escape responsibility for fixing a serious problem. And innocent people — and police officers — are dying as a result.

On climate change, the duck-and-cover usually involves pointing the finger at others. It’s China-this and India-that. But wait a second. This is the United States of America! When there’s a major challenge, we don’t wait for others to act. We lead! And we lead by example. That’s what all of us here are doing.

This conference has highlighted just how much local leadership there is on the issue of climate change and how many innovative new projects are going on in cities around the country: Seattle’s incentives for greening existing buildings, Los Angeles’s million tree initiative, Miami’s bus rapid transit program — and the list goes on. When we developed our long-term sustainability plan in New York, which we call PlaNYC, we made no apologies for stealing the very best ideas — and we came up with some of our own, including converting our 13,000 taxis to hybrids or high-efficiency vehicles. This will not only help clean our air and reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, it will save each driver about $4,500 a year in gas costs.

Cities and states are both taking action, but the fact is, no matter how far we push the boundaries of the possible, there will be no substitute for federal leadership. Leadership is not waiting for others to act, or bowing to special interests, or making policy by polling or political calculus. And it’s not hoping that technology will rescue us down the road or forcing our children to foot the bill. Leadership is about facing facts, making hard decisions and having the independence and courage to do the right thing, even when it’s not easy or popular. We’ve all heard people say, “It’s a great idea, but for the politics.” And let me give you just one example from New York.

Last spring, as part of our PlaNYC initiative, we proposed a system of congestion pricing based on successful programs in London, Stockholm and Singapore. The plan would charge drivers $8 to enter Manhattan on weekdays from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., which would help us reduce the congestion that is choking our economy, the pollution that has helped produce asthma rates that are twice the national average, and the carbon dioxide that is fueling global warming.

Now, the question is not whether we want to pay, but how do we want to pay. With an increased asthma rate? With more greenhouse gases? Wasted time? Lost business? Higher prices? Or do we charge a modest fee to encourage more people to take mass transit and use that money to expand mass transit service? When you look at it that way, the idea makes a lot of sense, but for the politics, because no one likes the idea of paying more. But being up front and honest about the costs and benefits, we’ve been able to build a coalition of supporters that includes conservatives and liberals, labor unions and businesses, and community leaders throughout the city.

There is no problem that can’t be solved if we have the courage to confront it head-on — and put progress above politics. Mayors around the country are doing it — and those in Washington can, too. I believe it’s time for both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue to come together around a national strategy on climate change and to lead the way on an international strategy. And I believe that until they do, it’s our job as mayors to point the way forward. That’s why right after this conference, several of us will be testifying before a House committee that is holding a hearing on climate change here in Seattle. It’s why I’m pleased to announce that New York City has recently joined a new campaign being launched by The Climate Group called “Together.” It will unite businesses, think tanks, advocacy groups, faith-based organizations, and cities — and I urge all of the cities in this room to join, and to invite your neighbors. It will be a national effort to help all Americans make a difference in the fight against climate change. And it’s why next month, I will go to the U.N. climate change summit in Bali, in the South Pacific, as a guest participant, and to support our delegation.

It’s time for America to re-establish its leadership on all issues of international importance, including climate change. Because if we are going to remain the world’s moral compass — a role that we played throughout the 20th century, not always perfectly, but pretty darn well — we need to regain our footing on the world stage. That means ending the “go-it-alone” approach to foreign affairs that has never served America well. It didn’t work in the 1920s, when we tried to isolate ourself from the world, and it hasn’t work in recent years, when we’ve tried to stand above it, pretending that vital international treaties can simply be ignored. The fight against global warming is a test of America’s leadership — and not just on the environment.

Climate change presents a national security imperative for us, because our dependence on foreign oil has entangled our interests with tyrants and increased our exposure to terrorism. It’s also an economic imperative, because clean energy is going to fuel the future. Jobs are on the line here — good jobs of every kind: Farm jobs. Factory jobs. Engineering jobs. Sales jobs. Management jobs. If we don’t capture these jobs, they’ll just move overseas. Green energy is going to be the oil gusher of the 21st century, and if we’re going to remain the world’s economic superpower, we’ve got to be the pioneers — just as America always has been.

How do we do it? I think we need a strategy that embraces four basic principles, and I’d like to briefly outline them today. First, we need to increase investment in energy R & D. Right now, we’re spending just one-third of what we were in the 1970s. If we really want to be able to manufacture competitively priced biofuel and solar power, if we really want to sequester the carbon dioxide released from coal, we have to be willing to make the commitments that will drive private capital to these projects — and right now, we’re just not doing that.

Second, we have to stop setting tariffs and subsidies based on pork barrel politics. For instance, Congress is currently subsidizing corn-based ethanol at 50 cents a gallon — and you can argue that’s good agricultural policy, but you can’t argue that it’s good for consumers or the environment. Because it isn’t. Consumers pay more for food, and producing corn-based ethanol results in much more carbon dioxide than producing sugar-based ethanol. But are we subsidizing sugar-based ethanol? No! We’re putting a 50-cent tariff on it. Ending that tariff makes all the sense in the world, but for the politics. Everyone knows that politically driven policies are costing taxpayers billions while providing only marginal carbon reductions — but we need leaders who will do something about it!

Third, we have to get serious about energy efficiency — and the best place to start is with our cars and trucks. In 1975, Congress passed a law requiring fuel efficiency standards to double over 10 years, from 12 miles a gallon to 24, with incremental targets that auto manufacturers were required to meet. But since 1985, Washington has been paralyzed by special interests. If the same incremental gains had been adopted for the last two decades, think of where we would be now! We’d all be saving money at the pump, we’d be producing less air pollution and greenhouse gas, Detroit would be in a stronger competitive position and the “Big Three” may not have lost so many more jobs. (Just yesterday, Chrysler announced another 12,000 job cuts.)

Those job losses hurt hard-working Americans, and we have to ask ourselves: Do we want even more middle-class factory workers to be handed pink slips and left to look for service jobs at half the wages? Because that’s the direction we’re heading in if we continue to fall further and further behind other countries in producing fuel-efficient vehicles. The current Senate energy bill would raise Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards from 27.5 to 35 miles per hour by 2020. That’s nowhere near the leap we made from 1975 to 1985, and many foreign cars are already getting 35 miles to the gallon. Even so, U.S. automakers are trying to water down the Senate bill — and if Congress caves, you can bet the loudest cheers will be heard in Japan. Raising fuel efficiency standards is the best thing we could do for U.S. automakers — and it would’ve been done years ago, but for the politics.

Fourth and finally, we have to stop ignoring the laws of economics. As long as greenhouse gas pollution is free, it will be abundant. If we want to reduce it, there has to be a cost for producing it. The voluntary targets suggested by President Bush would be like voluntary speed limits — doomed to fail. If we’re serious about putting the brakes on global warming, the question is not whether we should put a value on greenhouse gas pollution, but how we should do it. This is where the debate is moving, and I’d like to briefly touch on the pros and cons of the two approaches that are most often discussed: creating a cap-and-trade system, and a putting a price on carbon.

Both of these ideas share the same goal: raising the cost of producing greenhouse gas pollution. If you want less of something, every economist will tell you to do the same thing: make it more expensive. Of course, none of us wants to pay more for electricity or gas or anything else. Rising energy costs, rising health costs, rising college tuition — the middle class is getting squeezed left and right. But raising the cost of pollution can actually save taxpayers money in the long run — and I’ll explain how in a minute. But first, you might be thinking: “Wait a second. Five years ago, oil was selling at $30 a gallon. Now it’s selling at more than $90, and we’re not buying any less of it. So why would raising the cost of carbon make any difference?” The answer is: It would and it wouldn’t. People are going to keep buying gas whether it costs $1 a gallon or $2.75 a gallon — or even more — because the demand for gas is inelastic. But the demand for coal is far more elastic than oil, and so if its price goes up, many power plants would likely switch to natural gas, which is much cleaner, and the 100 coal plants that are now on the drawing boards would likely convert to natural gas as well. Raising the cost of carbon would also make alternative energy sources more cost-competitive, which would lead more consumers and property owners to make the switch.

To raise the cost of carbon, we can take either an indirect approach — creating a cap-and-trade system of pollution credits — or a direct approach: charging a fee for greenhouse gas pollutants. The question is: Which approach would be more effective? I’ve talked to a number of economists on this issue, people like Gilbert Metcalf at the National Bureau of Economic Research, and every one of them says the same thing: A direct fee is the better approach — but for the politics. There’s that phrase again: “But for the politics!”

Cap-and-trade is an easier political sell because the costs are hidden — but they’re still there. And the payoff is more uncertain. Because even though cap-and-trade is intended to incentivize investments that reduce pollution, the price volatility for carbon credits can discourage investment, since an investment that might make sense if carbon credits are trading at $50 a ton may not make sense at $30 a ton. This price volatility can also lead to real economic pain. For instance, if 100 companies release higher emissions than they had planned for, they all have to buy more credits, which can create a very expensive bidding war. That’s exactly what’s happening in parts of Europe right now, and it’s going to cost companies there billions of dollars.

There are also logistical issues with cap-and-trade. The market for trading carbon credits will be much more complex and difficult to police than the market for the sulfur dioxide credits that eliminated acid rain. And there are political issues — because the system is subject to manipulation by elected officials who want to hand out exemptions to special interests. A cap-and-trade system will only work if all the credits are distributed from the start — and all industries are covered. But this begs the question: If all industries are going to be affected, and the worst polluters are going to pay more, why not simplify matters for companies by charging a direct pollution fee? It’s like making one right turn instead of three left turns. You end up going in the same direction, but without going around in a circle first.

A direct charge would eliminate the uncertainty that companies would face in a cap-and-trade system. It would be easier to implement and enforce, it would prevent special interests from opening up loopholes and it would create an opportunity to cut taxes.

I was in England a month ago talking to the Conservative Party, which has proposed a series of revenue-neutral “green taxes” that would be offset by reductions in other taxes. I believe that approach merits consideration — and the most promising idea I’ve heard is to use the revenue from pollution pricing to cut the payroll tax. After all: Employment is good, pollution is bad. Why shouldn’t we lower the cost of the good and raise the cost of the bad? Studies show that a pollution fee of $15 for every ton of greenhouse gas would allow us to return about $500 a year to the average taxpayer. And a charge on pollution would be less regressive than the payroll tax, because the more energy you consume, the more you would pay. That would give us all of us an incentive to reduce our energy use — whether that’s buying a more fuel efficient appliance, or making the switch to compact fluorescent light bulbs, as we’ve done in New York’s City Hall – and as I’ve done in my own home. Under this approach, even though energy costs would rise, the savings from tax cuts and energy efficiencies could, over the long run, leave consumers with more money in their pockets.

Creating a direct charge for greenhouse gas pollution would also incentivize the kinds of innovation that a cap-and-trade system is designed to encourage — without creating market uncertainty. To do this, a portion of the revenue from the pollution charge would be used to create an innovation fund, which would finance tax credits for companies that reduce their greenhouse gas pollution. As a result, companies would have two big incentives to reduce their pollution: minimizing the charges they would have to pay and maximizing their tax savings. And unlike a cap-and-trade system, the certainty of tax credits would be more likely to lead companies to make the long-term investments in clean technology that will allow us to substantially reduce greenhouse gas pollution.

Both cap-and-trade and pollution pricing present their own challenges — but there is an important difference between the two. The primary flaw of cap-and-trade is economic — price uncertainty. While the primary flaw of a pollution fee is political, the difficulty of getting it through Congress. But I’ve never been one to let short-term politics get in the way of long-term success. The job of an elected official is to lead – not to stick a finger in the wind. It’s to stand up and say what we believe — no matter what the polls say is popular or what the pundits say is political suicide.

From where I sit, having spent 15 years on Wall Street and 20 years running my own company, the certainty of a pollution fee — coupled with a tax cut for all Americans — is a much better deal. It would be better for the economy, better for taxpayers and — given the experiences so far in Europe — it would be better for the environment. I think it’s time we stopped listening to the skeptics who say, “But for the politics” and start being honest about costs and benefits. Politicians tend to prefer cap-and-trade because it obscures the costs. Some even pretend that it will lower costs in the short run. That’s nonsense. The costs will be the same under either plan — and if anything, they will be higher under cap-and-trade, because middlemen will be making money off the trades. (I happen to love middlemen. They use Bloomberg terminals and support my daughters. But what’s right is right!)

For the money, a direct fee will generate more long-term savings for consumers, and greater carbon reductions for the environment. And I don’t know about you, but when the economists say one thing and the politicians say another, I’ll go with the economists.

Of course, I also understand that you can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Whether it’s a direct fee or cap-and-trade, we can’t be afraid to try something — to do something — to act. As mayors, we’re all familiar with those who respond to every problem by saying, “Do another study,” or by scaring voters with doom-and-gloom predictions. That approach is why we have health care costs that have spiraled out of control, it’s why we have public school systems that were allowed to collapse, and it’s why we’re still fighting poverty with the same old programs that haven’t worked.

But remember, this is America! We can’t be afraid to lead, to innovate, to experiment. Cities aren’t afraid. We’re showing that we can do better, we can make progress, and we can do it in a way that is good for the environment and the economy. It’s time for Washington to do the same and to show the world that America is ready to be a leader. When our representatives run for re-election or higher office, they talk about “a chicken in every pot.” But why not tell us who’s going to pay, how it’s going to work, when it’s going to be implemented, and if it doesn’t work, what’s Plan B? We need our leaders to have the courage to talk about and implement real climate change solutions, not just because it’s good for the world, but because it’s good for America, our environment, our national security and our economy. Make no mistake: Real jobs are on the line here — because cleaner energy sources are going to be a cornerstone of the 21st-century economy.

If we’re going to remain the world’s economic superpower, we have to create predictable incentives that will drive technological innovations and allow us to lead the world in developing clean, reliable and affordable energy. We can do it! If we stop saying: But for the politics!

In the weeks and months ahead, our job is not just to continue innovating — but to demand that those in Washington join us. Tell them that it’s O.K. to stand up and be honest about the costs and benefits of real solutions. We’ve done it — and we’ve not only lived to tell the tale, we’ve won support and respect from our constituents. They can, too. And we’ve got to hold them accountable for doing it. So let’s get to work.

Should There Be a Price on Carbon?

Experts Debate: Carbon Tax vs. Cap & Trade, Subsidies (WSJ)

Rep. McDermott (D-Wa) Introduces Bold "Managed Price" Carbon Tax Bill

As brutal drought and punishing heat waves remind voters how deeply climate affects our lives, Washington State Democrat Jim McDermott today stepped up to the climate plate. Rep. McDermott, a 12-term House member who sits on the powerful tax-writing Ways & Means Committee, introduced the “Managed Carbon Price Act of 2012.” His carbon tax bill would substantially reduce emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases by predictably raising their costs relative to energy efficiency, renewables and innovation.

The Carbon Tax Center estimates that by imposing a steadily rising “upstream” tax on polluters emitting the six principal greenhouse gases driving global warming, McDermott’s bill would reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by a whopping 30% within a decade. His elegant bill, just 21 pages of legislative text, would start modestly with a price of $12.50 per ton of CO2, but would then ramp up the cost of carbon pollution to $125 per ton of CO2 over a decade. (The actual price would fall within a tight, predictable price range. Non-CO2 greenhouse gases would be taxed at their CO2-equivalent rates.) CTC estimates that within a decade, McDermott’s price path would reduce greenhouse gas emissions almost twice as much as the most optimistic projections for prospective EPA regulations or the targets in the Waxman-Markey bill passed by the House in 2009 but dropped in the Senate the following year.

Consistent with World Trade Organization rules, McDermott’s bill would exempt U.S. exports of energy-intensive goods while imposing an equivalent pollution tax on imports. The bill would thus protect U.S. domestic energy-intensive trade-exposed industries from unfair competition while offering an irresistible (and growing) “carrot” for our trading partners to enact their own carbon taxes in order to capture a rising stream of carbon tax revenue that would otherwise flow to the U.S. Treasury.

The McDermott bill also obviates the need for emissions trading by requiring polluters to purchase permits as needed. It returns 75% of revenue directly to households through a monthly “dividend” for each adult (with a half share for each dependent). This provision eliminates regressive income effects on low- and middle-income households while preserving a clear price signal across the entire economy so that everyone is rewarded for efficiency, innovation and investment in renewable energy. The remaining 25% of the bill’s revenue would be dedicated to deficit reduction, a feature that is sure to be salient as Congress confronts the looming “fiscal cliff” next January.

CTC estimates that the revenue stream available for deficit reduction in the tenth year after enactment would be roughly $100 billion, even accounting for the 30% reduction in emissions.

Photo: Flickr — WSDOT

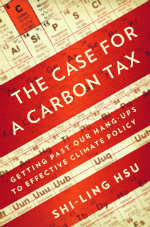

Book Review: The Case for a Carbon Tax, by Shi-Ling Hsu

Co-authored with Sieren Ernst, Environmental Markets Advisory.

“The Case For A Carbon Tax” (Island Press, 2011, 233 pp) brings to mind Hans Christian Andersen’s “ugly duckling” story. The word “tax” screams “cost” to most people, and so the beauty of a carbon pollution tax isn’t apparent on first glance. Prof. Hsu reveals the beauty as he shows why a gradually-rising carbon tax is the least costly and most effective policy for curbing the pollution driving global warming, and how enacting such a tax can usher in a new era of clean energy and efficiency.

“The Case For A Carbon Tax” (Island Press, 2011, 233 pp) brings to mind Hans Christian Andersen’s “ugly duckling” story. The word “tax” screams “cost” to most people, and so the beauty of a carbon pollution tax isn’t apparent on first glance. Prof. Hsu reveals the beauty as he shows why a gradually-rising carbon tax is the least costly and most effective policy for curbing the pollution driving global warming, and how enacting such a tax can usher in a new era of clean energy and efficiency.

Trained in engineering, law and economics, Shi-Ling Hsu, a law professor who is moving from the University of British Columbia to Florida State University, deftly marshals a multi-disciplinary “case” for a carbon tax. He opens by describing and comparing the four main climate policy tools: subsidies, regulations, cap-and-trade, and carbon taxes. Then he briskly articulates ten arguments for a carbon tax, emphasizing economic efficiency and the advantages of basing a coordinated international system on a simple, transparent tax.

Hsu is especially strong in rebuttal, answering the arguments against carbon taxes, including the oft-repeated assertion that a carbon tax is politically impossible. He dissects psychological “hang-ups” that have kept the public and elected officials from embracing carbon taxes. Hsu points to British Columbia’s enactment and implementation of North America’s first carbon pollution tax, arguing that it is broadly supported because its revenue is used to reduce taxes for individuals and businesses. As Hsu and Yoram Bauman wrote this week in their New York Times op-ed, “The Most Sensible Tax of All“:

On Sunday, the best climate policy in the world got even better: British Columbia’s carbon tax — a tax on the carbon content of all fossil fuels burned in the province — increased from $25 to $30 per metric ton of carbon dioxide, making it more expensive to pollute. This was good news not only for the environment but for nearly everyone who pays taxes in British Columbia, because the carbon tax is used to reduce taxes for individuals and businesses. Thanks to this tax swap, British Columbia has lowered its corporate income tax rate to 10 percent from 12 percent, a rate that is among the lowest in the Group of 8 wealthy nations. Personal income taxes for people earning less than $119,000 per year are now the lowest in Canada, and there are targeted rebates for low-income and rural households.

Hsu crisply articulates the theory of Pigouvian taxes — the idea of taxing pollution rather than productive activity. But he sidesteps the thorny question of how high to set a carbon tax and how rapidly to increase it. And he does not mention the potential efficiency advantages of using carbon tax revenues to reduce other taxes such as taxes on work and thereby use climate policy to improve overall economic well-being. (Economists call that a “double dividend.”) He notes that while British Columbia’s carbon tax is revenue-neutral, the regressive effects of carbon taxes can be addressed by a wide variety of other mechanisms, leaving substantial revenue for cash-strapped governments, as recent reports and a new book by the International Monetary Fund have stressed.

Hsu delves into the limitations of EPA regulations, which he shows cannot create the broad incentives for innovation and planning needed to drive carbon eminssions way down:

A [carbon] tax, by imposing a cost on every single ton of pollutant, constantly engages the polluter with the task of reducing her pollution tax bill. By contrast, a command and control scheme that mandates a one shot, irrevocable installation of pollution control equipment allows for the polluter to stop thinking about pollution reduction. Why, if compliance is achieved, should the polluter look for other ways to reduce?

There are further problems, too: EPA can too easily be persuaded or intimidated by industry into granting exemptions and relaxing standards. Hsu also glosses over the enormous effort that would be required to write and enforce permits for each of the thousands of point sources of CO2. One has to wonder where and how the already-stretched EPA (and state environmental agencies) would find funding for such a massive undertaking.

Hsu neatly unveils the hidden high cost of taxpayer-funded subsidies of renewables and supposed low-carbon fuels. Subsidies, along with regulations and cap-and-trade with offsets, are attractive to the public and Congress despite serious limitations on their effectiveness, because their costs are largely hidden. Not only is Congress notoriously ineffective at picking technology winners, but subsidies create “lock-in” to incumbent technologies and businesses, foreclosing opportunities to spur innovation. In contrast, as Hsu shows, a carbon pollution tax’s laser focus on CO2 pollution creates incentives for all low-carbon alternatives, leaving specific technology decisions to engineers rather than politicians.