(As published today in NYC-based Gotham Gazette. Footnotes appear at end. — C.K., May 13, 2022)

Like time in Steve Miller’s classic-rock song, New York’s decarbonization targets keep slipping into the future.

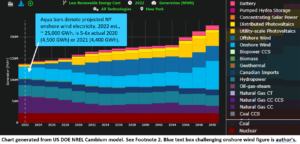

Highway widenings are spurring more driving. Suburban resistance to upzoning is locking in energy-demanding sprawl. Electricity from the state’s wind turbines shrank last year,1 even as climate advocates, relying on dodgy U.S. Energy Department modeling, overstate future carbon reductions from “electrifying everything.”2

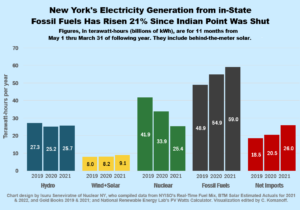

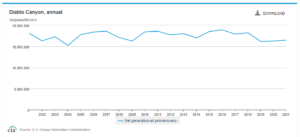

Promising developments like offshore wind leasing and new transmission to carry hydroelectricity from Quebec barely compensate, if at all, for carbon emissions unleashed by closing the Indian Point nuclear plant. As I have pointed out elsewhere, shutting existing zero-carbon power sources means that new ones don’t actually cut emissions; at best, they keep us running in place, punching huge holes in pledges to achieve a carbon-free power grid by 2040.

Promising developments like offshore wind leasing and new transmission to carry hydroelectricity from Quebec barely compensate, if at all, for carbon emissions unleashed by closing the Indian Point nuclear plant. As I have pointed out elsewhere, shutting existing zero-carbon power sources means that new ones don’t actually cut emissions; at best, they keep us running in place, punching huge holes in pledges to achieve a carbon-free power grid by 2040.

To this dreary picture, add crypto mining — enormous networks of electron-eating computers running 24-7 so that digital currencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum can maintain virtual “coins” or “tokens” in encrypted ledgers that bypass traditional third parties like banks.

From Buffalo and the Finger Lakes to the state’s northern tier, crypto entrepreneurs are building new generators or firing up retired ones to power their crypto mining operations. Other crypto sites draw on the grid.

Self-sourced or not, the requisite electricity ends up forcing additional burning of fossil fuels, as Sierra Club researchers documented in extensive comments this week to the President’s Office of Science and Technology Policy, pushing the state’s ambitious decarbonization goals further out of reach. To what end?

In Uber’s Footsteps

Enigmatic, opaque, futuristic — crypto-currency cries out for historical analogues. Here’s one: Uber.

Uber burst on the scene in the early 2010s not as a new form of transportation but a new kind of network enabling a reconfiguration of transportation. Its appeal was tailored around three promises: it would enhance traffic efficiency by eliminating cruising for fares; it would extend convenient for-hire vehicle service outside Manhattan; and it would end service refusals to people of color.

The packaging — sleek and app-enabled — augured a frictionless, digital future. With a few taps New Yorkers could summon a chariot.

The results were mixed. We now know that stockpiling of Ubers in Manhattan has wrought even more gridlock than taxi cruising. But Uber did broaden access to for-hire vehicles, even as it bled ridership from the MTA and, worse, rained economic ruin on the incumbent yellow-cab industry.

Bitcoin and other crypto-currencies come with their own glossy promises, though these are more chameleon-like. (Earlier this year New York Times columnist Paul Krugman disparaged them as “word salad.”) Among them, as Annie McDonough reported recently in City & State, is the prospect of liberation from ingrained discriminatory banking and lending by U.S. financial institutions.

“[Crypto backers] see the technology as an economic equalizer,” writes McDonough. “A tool not just for the rich to get richer, but for people who have been discriminated against by banking institutions or locked out of investment opportunities, including people of color and low-income communities.”

Really? In New York, and almost certainly anywhere else, unbanked households overwhelmingly lack the requisite credit history or liquid assets — bank accounts, debit cards, credit cards — to purchase cryptocurrency tokens. Moreover, scammers and grifters are finding crypto fertile territory for high-tech swindles, as New York Times columnist Farhad Manjoo noted this month. An arguably safer and more effective way to root out credit segregation would be to speed Biden administration rulemaking to add teeth to the Community Reinvestment Act — the 1977 law intended to repair decades of redlining.

The emergence of crypto-front groups like the National Policy Network of Women of Color in Blockchain demonstrates the industry’s readiness to exploit deep-seated bitterness over legacy redlining. So does the participation in crypto lobbying of Bradley Tusk, the one-time Mike Bloomberg consigliere who a decade ago deftly deployed Black fury over persistent taxi discrimination to help Uber eradicate cabbies’ exclusive right to pick up street hails in Manhattan and subsequently helped fend off serious regulation of the app-ride industry for several crucial years.

Let’s Burn Up The Grid

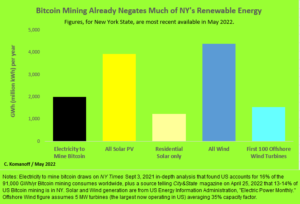

There is no registry of electricity consumed by crypto mining in New York State. Worldwide, though, crypto burns through an estimated 91,000 gigawatt-hours (or, 91 billion kilowatt-hours) of electricity annually, according to a New York Times survey of crypto last September. Some 16% of that, or 15,000 GWh, is said to be consumed in the United States.

While New Yorkers are accustomed to thinking of our state as resource-poor, crypto miners are now exploiting half-a-dozen hydro power sites and formerly boarded-up fossil-fuel plants in northern and western New York. One industry source cited by City & State estimates that 13-14% of his company’s U.S. crypto mining takes place in our state. Extrapolating that share across the industry, crypto is annually consuming 2,000 GWh of electricity in New York State — a figure that could grow not just with increased transactions but with ever-more complex digital encryption.

While New Yorkers are accustomed to thinking of our state as resource-poor, crypto miners are now exploiting half-a-dozen hydro power sites and formerly boarded-up fossil-fuel plants in northern and western New York. One industry source cited by City & State estimates that 13-14% of his company’s U.S. crypto mining takes place in our state. Extrapolating that share across the industry, crypto is annually consuming 2,000 GWh of electricity in New York State — a figure that could grow not just with increased transactions but with ever-more complex digital encryption.

Even holding at 2,000 GWh, that’s a lot of juice: more than the electricity generated last year from all the solar panels on residential buildings in the state, or more than what will come from the first 100 promised offshore wind turbines once that industry launches (see graph below). And, though crypto in New York consumes less electricity than all current solar or wind, that comparison is of no comfort, as those renewable sources need to be displacing fossil fuels (primarily fracked gas) from the state’s grid — which they can’t do if their output is effectively being consumed mining Bitcoin.

The operative word, “effectively,” encompasses two distinct but complementary dynamics. Grid dynamics dictate that any new locus of demand such as Bitcoin forces utilities to draw more heavily on fossil-fuel generators, because the non-carbon sources — nukes as well as renewables — already run as flat-out as they can. The climate dynamic is that from a statewide perspective, additional use of fossil-fuel generators negates the carbon-reduction benefits that wind and solar and nuclear would otherwise provide.

This perspective casts a harsh light on claims that a particular crypto installation is being renewably sourced. Connecting crypto to a refurbished hydro dam or solar or wind farm may sound green, but all those whirring hard drives are really siphoning off carbon-free electricity that now “won’t be available to power a home, a factory or an electric car,” as the Times’ 2021 story put it. (One hopes that the irony of crypto adherents miscounting green electrons doesn’t carry over to their currency bookkeeping.)

Carbon Tax vs. Crypto?

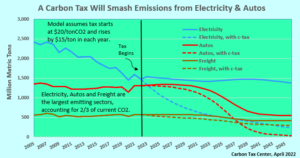

A stiff New York State carbon tax could slow and even reverse the rise of cryptocurrency here (likewise nationwide).

The rise in electricity prices would undermine whatever competitive advantage Bitcoin miners gain from locating in New York. Some miners would leave, new ones would stay away, and those who stay would endeavor to blunt the impact of the tax by upgrading their efficiency.

Not only that, crypto miners seeking zero-carbon generation increasingly would find themselves competing with non-crypto businesses seeking to contain their power costs. Other businesses, less power-intensive per dollar of revenue, would be in position to outbid the crypto companies.

The prospective flight to other jurisdictions could help build momentum to tax carbon emissions there as well, as more states and countries come to conclude that crypto jobs and revenues aren’t worth straining their grids, not to mention trashing their air-sheds and stealing their quiet.

This isn’t to hold out carbon taxing as a one-bullet crypto killer — we need many bullets for that, the bigger the better — but to illustrate its broad potential to stop frivolous (and in this case imbecilic) new uses of electricity before they can gain a foothold.

This isn’t to hold out carbon taxing as a one-bullet crypto killer — we need many bullets for that, the bigger the better — but to illustrate its broad potential to stop frivolous (and in this case imbecilic) new uses of electricity before they can gain a foothold.

Why not regulate crypto away? That battle would consume years, tying down policy resources while emissions continued to spew. Worse, we have neither the time nor the ability to see around corners required to enact, piecemeal, restraints on each new locus of energy demand.

Even as energy-efficiencies continue to do wonders — total U.S. electricity use last year was just a few percent higher than in 20053 — underpriced electricity elicits new hellspawns of needless use that undo much of that progress.

Carbon taxes by themselves can’t solve everything that ails climate. But they could, for a change, get the solutions out in front of the problems.

***

Charles Komanoff, long-time New York policy analyst and environmental activist, directs the Carbon Tax Center. On Twitter @Komanoff.

1US Energy Information Administration, “Electric Power Monthly,” Table 1.14.B, “Utility Scale Facility Net Generation from Wind,” shows 4,522 GWh in New York State in 2020 and 4,387 GWh in 2021.

2To estimate future carbon reductions from the December 2021 New York City ban on gas heating and cooking in new buildings, the law’s proponents and the Dec. 15, 2021 New York Times story reporting on it both cited a Dec. 10, 2021 post, Stopping Gas Hookups in New Construction in NYC Would Cut Carbon and Costs, by the consultancy RMI. The RMI authors note that their calculations employed future electricity grid emission factors modeled by U.S. DOE’s National Renewable Energy Lab’s “Cambium” dataset. Examination of that dataset reveals, inter alia, that it assumes a non-existent five-fold increase in New York State on-shore wind-generated electricity from 2020 to 2022.

3Figures from US Energy Information Administration, “Electric Power Monthly,” Table 7.2a Electricity Net Generation: Total (All Sectors)” supplemented by Table 10.6 (“Electricity Net Generation from Distributed Solar”) indicate total U.S. electricity generation of 4,164,565 GWh in 2022 and 4,055,785 GWh in 2005. For those interested, the implied compound annual average growth rate over those 17 years is a minuscule 0.17 percent.

Correction: This post was amended on May 26 to reflect the fact that New York’s estimated 13-14% share of U.S. crypto mining applies to a single crypto company rather than industry-wide. The extrapolation to other companies is the author’s, not the source’s.

May 16 addendum: We strongly recommend How crypto made me fall in love with carbon pricing all over again, an April 27 essay by Frontier Group energy analyst Tony Dutzik covering the intersection of crypto mining, carbon pricing, energy demand and Jevons Paradox.

Amen. The failures propping up US carbon emissions are multiple. Not just Senator Joe Manchin, who torpedoed President Biden’s Build Back Better clean-energy legislation. Not just the Senate Republicans, any one of whom could have cast the critical 50th vote. And not just Big Carbon, whose

Amen. The failures propping up US carbon emissions are multiple. Not just Senator Joe Manchin, who torpedoed President Biden’s Build Back Better clean-energy legislation. Not just the Senate Republicans, any one of whom could have cast the critical 50th vote. And not just Big Carbon, whose

I know that record well. Not long ago, I did a study comparing California’s rate of decarbonizing its economy to the rest of the country’s. I found that from the mid-1970s to 2016, California drove down its use of fossil fuels per unit of economic activity nearly 20 percent faster than the other 49 states. Had those states matched California’s pace, I calculated, the country would now, each year, be eliminating 1,200 megatonnes of CO2, an amount equivalent to the carbon emissions from our entire fleet of passenger cars.

I know that record well. Not long ago, I did a study comparing California’s rate of decarbonizing its economy to the rest of the country’s. I found that from the mid-1970s to 2016, California drove down its use of fossil fuels per unit of economic activity nearly 20 percent faster than the other 49 states. Had those states matched California’s pace, I calculated, the country would now, each year, be eliminating 1,200 megatonnes of CO2, an amount equivalent to the carbon emissions from our entire fleet of passenger cars.

Owen’s article, which is well worth reading for its narrative power and climate relevance as well as its iconoclasm, was his latest exposition of Jevon’s Paradox, the phenomenon by which increases in energy efficiency lower the price of “energy services” and thus lead to more use, undercutting the efficiency gain. The antidote, of course, is to ensure the energy services — cooling, travel, lighting, and so forth — don’t plunge in price by raising the price of energy provision, as I pointed out a decade ago in a post in Grist,

Owen’s article, which is well worth reading for its narrative power and climate relevance as well as its iconoclasm, was his latest exposition of Jevon’s Paradox, the phenomenon by which increases in energy efficiency lower the price of “energy services” and thus lead to more use, undercutting the efficiency gain. The antidote, of course, is to ensure the energy services — cooling, travel, lighting, and so forth — don’t plunge in price by raising the price of energy provision, as I pointed out a decade ago in a post in Grist,