This page features editorial positions by newspapers, magazines, etc. (rather than merely opinions expressed by columnists or reporters). Half a dozen other pages with different “supporter” categories may be accessed via the “Progress” tab in our menu bar.

The New York Times

Editorials at the Times carry the imprimatur of the editorial board. In years past, the Times repeatedly urged only that nations “put a price” on carbon emissions — a vague formulation that has often connoted support for cap-and-trade. In 2015, the board finally began calling for an explicit carbon tax, and opened 2016 citing British Columbia’s successful carbon tax:

Proof That a Price on Carbon Works (January 19, 2016):

British Columbia started taxing emissions in 2008. One big appeal of its system is that it is essentially revenue-neutral. People pay more for energy (the price of gasoline is up by about 17 cents a gallon) but pay less in personal income and corporate taxes. And low-income and rural residents get special tax credits. The tax has raised about $4.3 billion while other taxes have been cut by about $5 billion. Researchers have found that the tax helped cut emissions but has had no negative impact on the province’s growth rate, which has been about the same or slightly faster than the country as a whole in recent years.

The Paris Climate Pact Will Need Strong Follow-Up (December 14, 2015):

Much was said about how the agreement sent a strong “signal” to investors, and indeed, Paris was swarming with corporate chieftains and Silicon Valley heavyweights. But the strength of that signal will depend heavily on whether governments are willing to promote such investments while removing the tax subsidies that favor dirtier fossil fuels — perhaps to the point of embracing carbon taxes.

The Case for a Carbon Tax (June 6, 2015):

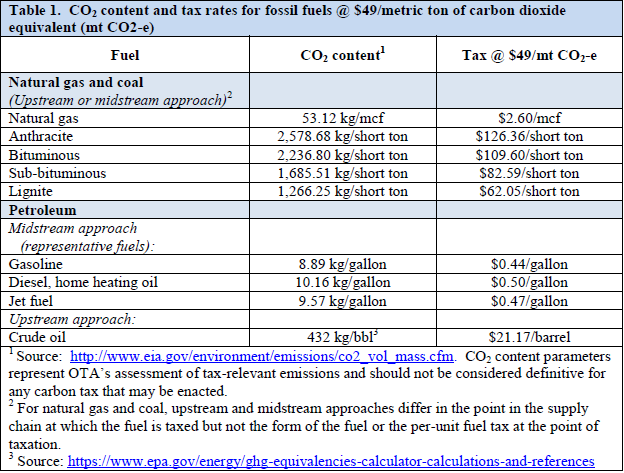

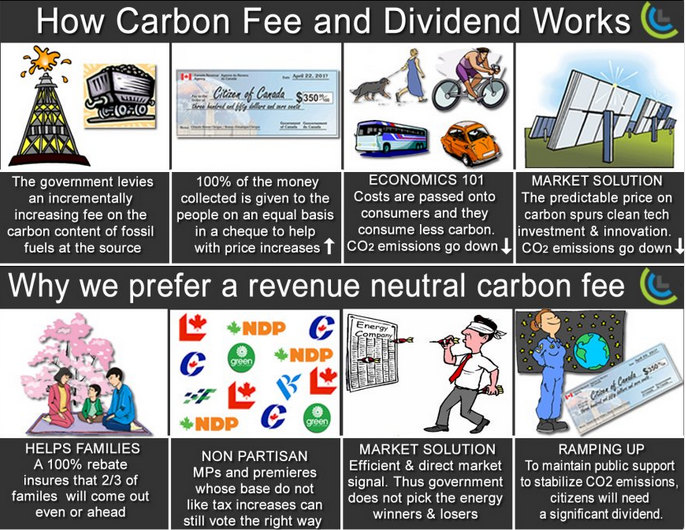

A carbon tax would raise the price of fossil fuels, with more taxes collected on fuels that generate more emissions, like coal. This tax would reduce demand for high-carbon emission fuels and increase demand for lower-emisson fuels like natural gas. Renewable sources like solar, wind, nuclear and hydroelectric would face lower taxes or no taxes. To be effective, the tax should also be applied to imported goods from countries that do not assess a similar levy on the use of fossil fuels.

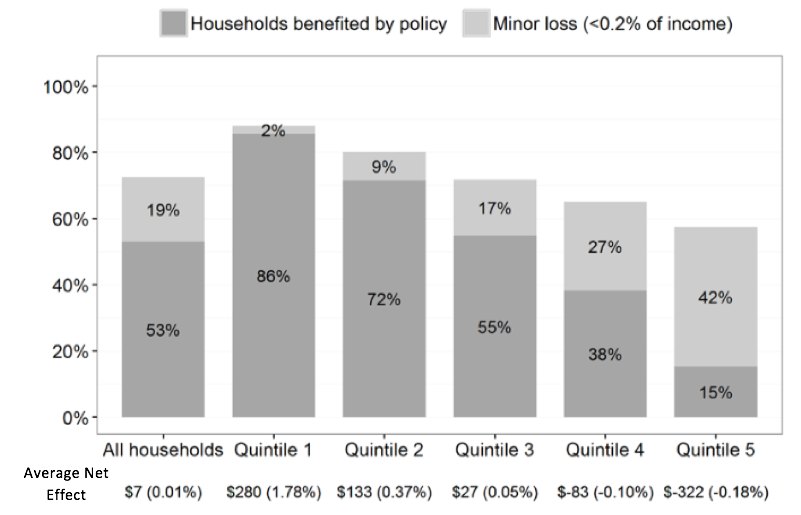

Revenue generated by carbon taxes could be used for a variety of purposes. A lot of the money should surely be given to households, especially the poorest, through tax credits or direct payments to offset the higher prices they would have to pay for gasoline, electricity and other goods and services because of the tax. Some of the money could be used to invest in renewable energy and public transportation, or to lower other taxes.

Global Warming and Your Wallet (July 6, 2007): “When the market, on its own, fails to arrive at the proper price for goods and services, it’s the job of government to correct the failure… We are now using the atmosphere as a free dumping ground for carbon emissions. Unless we — industry and consumers — are made to pay a significant price for doing so, we will never get anywhere.”

Warming Up on Capitol Hill (March 25, 2007): “Forcing polluters to, in effect, pay a fee for every ton of carbon dioxide they emit will create powerful incentives for developing and deploying cleaner technologies.”

The Truth About Coal (Feb. 25, 2007): “There is a need to put a price on carbon to force companies to abandon older, dirtier technologies for newer, cleaner ones. Right now, everyone is using the atmosphere like a municipal dump, depositing carbon dioxide free. Start charging for the privilege and people will find smarter ways to do business. A carbon tax is one approach. Another is to impose a steadily decreasing cap on emissions and let individual companies figure out ways to stay below the cap.”

Avoiding Calamity on the Cheap (Nov. 3, 2006): “Since the dawn of the industrial revolution, the atmosphere has served as a free dumping ground for carbon gases. If people and industries are made to pay heavily for the privilege, they will inevitably be driven to develop cleaner fuels, cars and factories.”

The Washington Post

Carbon tax is best option Congress has (May 7, 2013):

Sen. Max Baucus (D-Mont.), chairman of the Finance Committee, announced last month that he wants to spend the rest of his final term in office reforming the tax code , and there are signs that Republicans want an overhaul this year, too…

No honest tax reform paper, for example, would be complete without discussion of a carbon tax, an elegant policy Congress could immediately take off the shelf. It would make polluters pay for their own pollution, which is the best way to encourage greener thinking. It would cut emissions without overspending national wealth on grandiose central planning or command-and-control regulation. And it would raise revenue, which lawmakers could use for debt reduction, lowering other taxes, improving the social safety net or some combination. The carbon tax is one of the best ideas in Washington almost no one in Congress will talk about.

Those still worried about the economic effects need only consider how it could fit into a bigger tax-reform package such as the one Mr. Baucus wants to produce. Surely, Republicans should want to replace economy-sapping taxes on labor or business in return for a much more efficient tax on pollution. Democrats should be pushing for some of the revenue to pump up programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit to ensure the carbon tax doesn’t sting consumers, particularly those least able to afford it.

Lawmakers should read the Finance Committee staff’s work and then consult a recent analysis by the Brookings Institution’s Adele Morris , who found that even a relatively modest carbon tax could produce nearly a trillion dollars in debt reduction over two decades, significantly drop other tax rates and enhance anti-poverty programs.

The carbon tax (November 10, 2012):

EARLY WEDNESDAY, delivering his victory speech in Chicago, President Obama elevated an issue that had hardly come up during the campaign. “We want our children to live in an America,” he said, “that isn’t threatened by the destructive power of a warming planet.”

Later that day, Senate Majority Leader Harry M. Reid (D-Nev.) told reporters that climate change is an important issue and that he wants to “address it reasonably” — particularly following big storms in the Northeast that have highlighted rising sea levels and other dangers associated with global warming.

House Speaker John R. Boehner (R-Ohio), meanwhile, spoke about cooperating with Democrats on urgently needed budget reform

Now if there were just some policy that would reduce carbon emissions and raise federal revenue . . .

A tax on carbon, of course, is that policy, and lawmakers and the president should be discussing it. The idea is to put a simple price on emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases — some dollar amount per ton of CO² — that steadily increases at a pre-set rate.

This is the best plan lawmakers can take off the shelf to fight global warming. As an added benefit, it would reduce dependence on imported oil. If businesses and consumers had to pay something for the otherwise invisible costs of their actions — in this case, pollution — they would be more careful. Their combined preferences, not those of Congress or bureaucrats, would determine how to wring carbon out of the economy.

Homeowners might turn down their thermostats or weatherize their windows. Power companies would devise the cheapest ways to reduce the carbon dioxide they emit, without the government ordering them to build this or to refrain from that. At first, they would probably burn more natural gas and less coal, a cheap way to cut lots of emissions quickly. In the long term, the demand for green technologies would expand, and with it private investment.

Sorry Record – Waiting for breakthrough technologies is not the way to reduce greenhouse gases (July 11, 2006)

[The Administration] has resisted taxing carbon use, preferring instead to provide incentives for oil and gas extraction — just the opposite of what’s needed.

Some Positive Energy — Now Start Talking About a Carbon Tax, (June 25, 2007).

As important as many of the measures in [the Senate energy] bill are, they amount to only tinkering at the margins of a serious problem. What the Senate bill doesn’t do — and what the House bill won’t do when it is brought to the floor for consideration next month — is spark a necessary debate on the imposition of a cap-and-trade system or a carbon tax. This must be on the agenda after the Fourth of July recess when the Senate is expected to take up global warming. Sooner or later, Congress will have to realize that slapping a price on carbon emissions and then getting out of the way to let the market decide how best to deal with it is the wisest course of action.

Los Angeles Times

How California can best fight climate change (July 14, 2014):

A carbon tax that pushes up gas prices would give all California drivers reason to be gas-thrifty. They could then decide whether to use their tax credit to offset the increased cost of buying gas or find ways to reduce gas purchases and use the credit for other purchases. Substantially larger tax credits would go to lower-income residents and perhaps to rural residents for whom public transit isn’t available. Some of the money could be set aside for rebates to residents who buy fuel-efficient cars, or to agricultural operations that switch to cleaner farm vehicles or methane-capture technologies.

The L.A. Times ran two stirring editorials in May-June 2007 that powerfully made the case for taxing carbon. Here are excerpts:

Time to Tax Carbon, (May 28, 2007):

There is a growing consensus among economists around the world that a carbon tax is the best way to combat global warming, and there are prominent backers across the political spectrum … Yet the political consensus is going in a very different direction. European leaders are pushing hard for the United States and other countries to join their failed carbon-trading scheme, and there are no fewer than five bills before Congress that would impose a federal cap-and-trade system. On the other side, there is just one lonely bill in the House, from Rep. Pete Stark (D-Fremont), to impose a carbon tax, and it’s not expected to go far.

The obvious reason is that, for voters, taxes are radioactive, while carbon trading sounds like something that just affects utilities and big corporations. The many green politicians stumping for cap-and-trade seldom point out that such a system would result in higher and less predictable power bills. Ironically, even though a carbon tax could cost voters less, cap-and-trade is being sold as the more consumer-friendly approach.

A well-designed, well-monitored carbon-trading scheme could deeply reduce greenhouse gases with less economic damage than pure regulation. But it’s not the best way, and it is so complex that it would probably take many years to iron out all the wrinkles. Voters might well embrace carbon taxes if political leaders were more honest about the comparative costs.

Reinveting Kyoto, (June 11, 2007):

A better treaty [than Kyoto] would scrap the unworkable carbon-trading scheme and instead impose new taxes on carbon-based fuels. As recently explained in the first installment of this series [Time to Tax Carbon, above], carbon taxes avoid many of the pitfalls of carbon trading. They would produce an equal incentive for every nation to clean up without relying on arbitrary dates or caps, or transferring money from one nation to another. They’re also much less subject to corruption because they give governments an incentive to monitor and crack down on polluters (the tax money goes to the government, so the government wins by keeping polluters honest)… Real solutions to global warming, such as carbon taxes, won’t come cheap — they’ll make power bills steeper and gas prices even higher than they are now. But the economic news isn’t all bad. Much of the clean technology of the future will probably be developed in the United States and sold overseas. Think of [a carbon tax] as a novel way of reducing our trade deficit with China while building a cleaner world.“

For the strong critique of cap-and-trade in the Time to Tax Carbon editorial, click here.

Other Newspapers

Albany Times-Union:

THE ISSUE: Evidence of a warming planet is clear and obvious.

THE STAKES: A carbon tax is needed to stave off a looming global crisis.

[Fossil fuel subsidies] are an absurd use of public finances, and must be eliminated as quickly as possible. That long-overdue move must be coupled with a stiff carbon tax that makes fossil fuels artificially and increasingly expensive. Such a tax would immediately make greener energy more competitive, and encourage private enterprise to develop new and better technologies. And it would acknowledge that fossils fuels have a negative societal cost that is increasingly intolerable.

Here’s another idea with merit: an import tax that charges manufacturers for the carbon impact of their products. Such tariffs, which are now being weighed by the European Union and Democrats in Congress, would leverage American buying power to force global changes and reduce concern that fighting climate change domestically puts the country’s economy at a global disadvantage.

Certainly, carbon taxes and tariffs would hit lower-income Americans too hard. That’s why both must be structured with rebates that alleviate the pain.

But as 100-year storms become 10- or 5-year storms, the cost of our stubborn inaction grows increasingly clear. The time for change is now, if not sooner.

Editorial: How soon is now?, Sept 8, 2021.

Detroit Free Press:

A tax on carbon dioxide emissions, phased in gradually but relentlessly, would be the most transparent and efficient step this country could take in the search for energy independence and reductions in many emissions, including carbon dioxide. It would send a hugely important signal to the markets — for cars and for alternative energy sources such as windmills and solar collectors, in particular — that innovation and conservation are essential. Consumers are going to pay for any measures taken to reduce greenhouse gases and shift away from dependence on foreign petroleum. But most politicians choose instead to hide the costs by placing expensive demands on automakers and by dispensing subsidies for alternative fuels, such as ethanol, that become a hidden tax burden. A cap-and-trade system for emissions also would have disguised costs. Keep Carbon Tax in the Mix of Solutions, July 12, 2007.

Chicago Tribune:

[T]he ultimate goal should not be to reduce the price consumers pay at the pump. It should be to reduce the amount going to oil producers. Global warming is more than ample grounds for levying taxes on carbon-based fuels, including gasoline, to reduce emissions. But those taxes would fall partly on foreign oil producers. By cutting consumption, they promise to put downward pressure on world crude oil prices—weakening OPEC and stemming the flow of dollars to anti-American regimes. American consumers have a choice: They can pay high prices to oil producers or to themselves. The tax proceeds can be used to finance programs of value here at home or to pay for cuts in other taxes—even as they curb the release of carbon dioxide. Pump Pain, May 20, 2008.

Christian Science Monitor:

Consumption taxes, after all, are often designed to wean people off bad behavior, such as smoking. A 90 percent drop in these emissions is probably what’s needed to limit any rise in atmospheric warming to 2 degrees Celsius, a goal that many scientists recommend. Most presidential candidates do endorse pinching pocketbooks, but only indirectly, such as by calling for higher fuel efficiency in vehicles and a cap on greenhouse-gas pollution from company smokestacks. Such demands on industry have the advantage of creating more certainty in reducing emissions, but they are complex to enforce. Gore would do both: tax carbon use and cap emissions. Putting a crimp on global warming can’t be done solely by promoting new energy technologies and voluntary conservation. Consumers of oil and coal need a direct tax shock. Christian Science Monitor, July 5, 2007.

The Monitor was even more direct in a pair of editorials on Oct. 25 and 26. In the first, Be Wary of Complex Carbon Caps, the Monitor noted the loopholes, fraud and other problems that have hamstrung carbon cap-and-trade programs. In the second, A Tax on Carbon to Cool the Planet, the Monitor summarized the first editorial:

Indeed, caps may put the US on a knowable track to, say, an 80 percent reduction in carbon emissions by 2050. But as the previous Monitor’s View pointed out, the flaws in cap-and-trade plans as experienced in other nations – their complexity and vulnerability to fraud and special-interest lobbyists – would reduce the intended effect. They also take a long time to set up and get working right. And, in the end, they also raise energy prices for consumers, just not as directly as a tax.

The Monitor then concluded:

With Europe’s cap-and-trade system faltering, the US should be a leader in using a carbon tax, even if big polluters such as China don’t follow. As a last resort, the US could tax goods from countries that fail to cut their carbon emissions.

A carbon tax is not the whole solution. Regulations will still be needed, such as stiffer fuel-economy standards for cars and trucks. And the US should fund research into alternative fuels, too. All it takes is the political will to act.

Eugene (OR) Register-Guard:

The crisis presented by global warming demands a response that is simple, comprehensive and effective. A tax on carbon consumption is the only response in sight that both discourages the production of emissions that cause global warming, and finances the rapid transition to a post-carbon economy… “The best way to tax carbon fuels is at the point of production: at the wellhead, mine or biofuel plant. The added tax should be large – starting at the equivalent of $1 per gallon of gasoline, and increasing to the equivalent of $6 per gallon of gasoline over 10 years… The phase-in of high taxes on carbon fuels over 10 years will provide huge incentives for market-financed, market-driven, market-governed development of unsubsidized, safe, sustainable alternate energy sources, far more efficient uses of energy, and other alternate products and methods. (The Cold Truth, July 22, 2007).

Senator Sanders introduced his

Senator Sanders introduced his  On the Paris climate agreement: “While this is a step forward it goes nowhere near far enough. The planet is in crisis. We need bold action in the very near future and this does not provide that,”

On the Paris climate agreement: “While this is a step forward it goes nowhere near far enough. The planet is in crisis. We need bold action in the very near future and this does not provide that,”

We agree with pioneering climate-scientist

We agree with pioneering climate-scientist

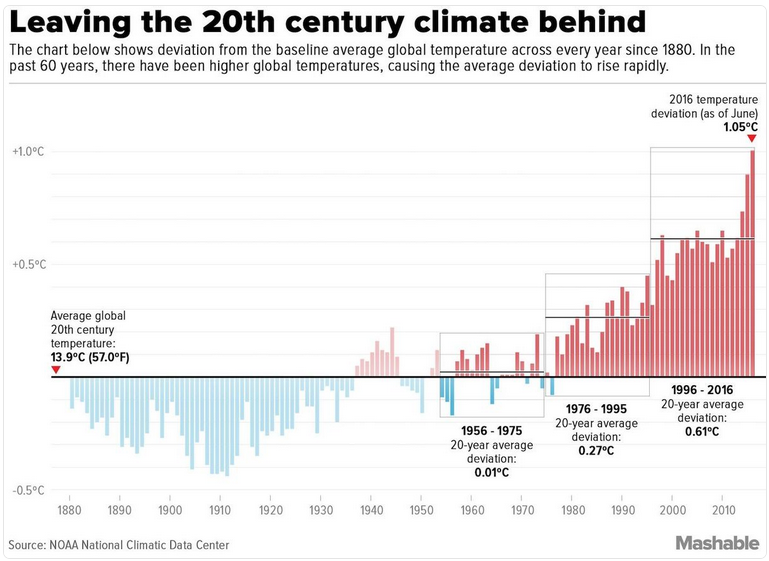

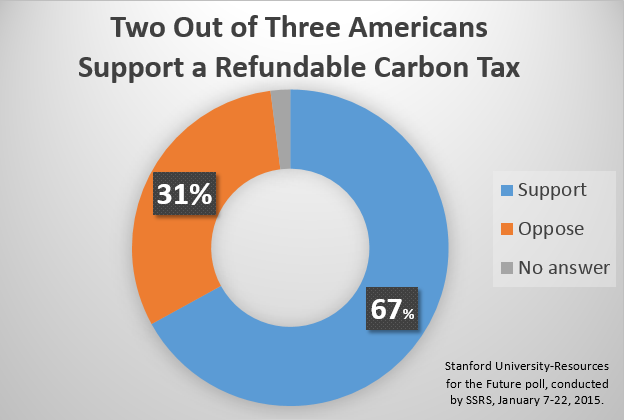

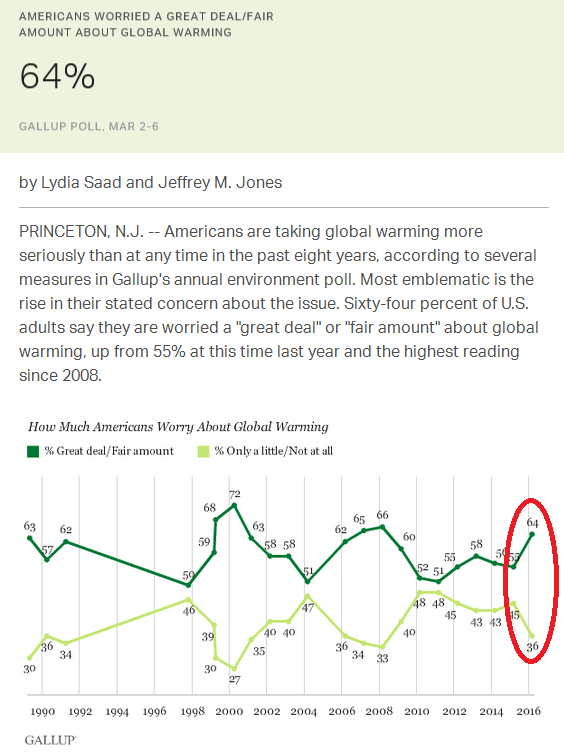

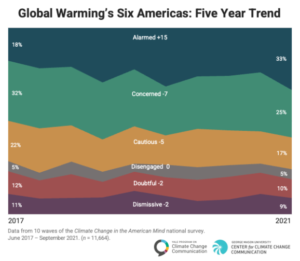

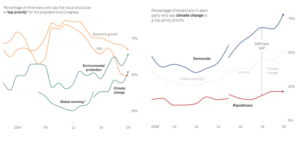

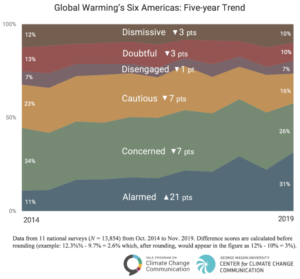

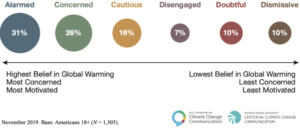

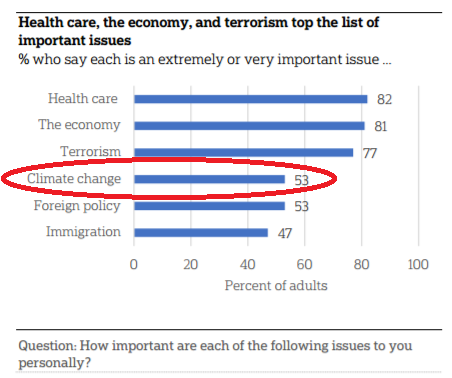

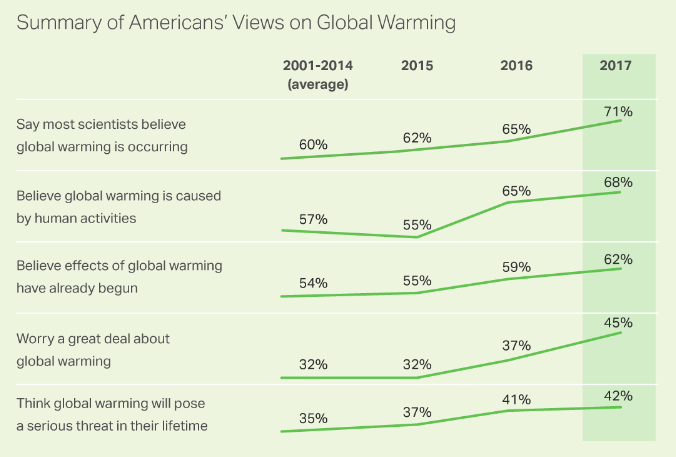

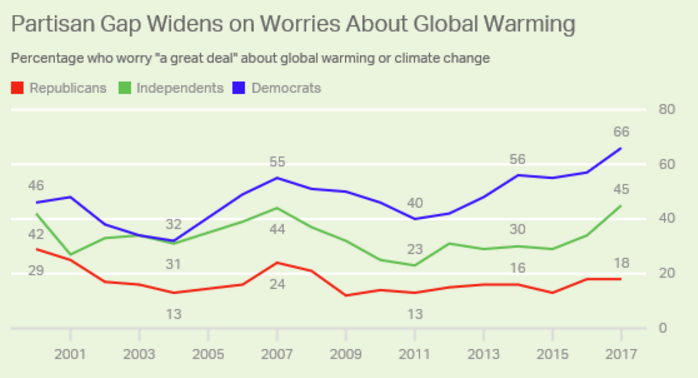

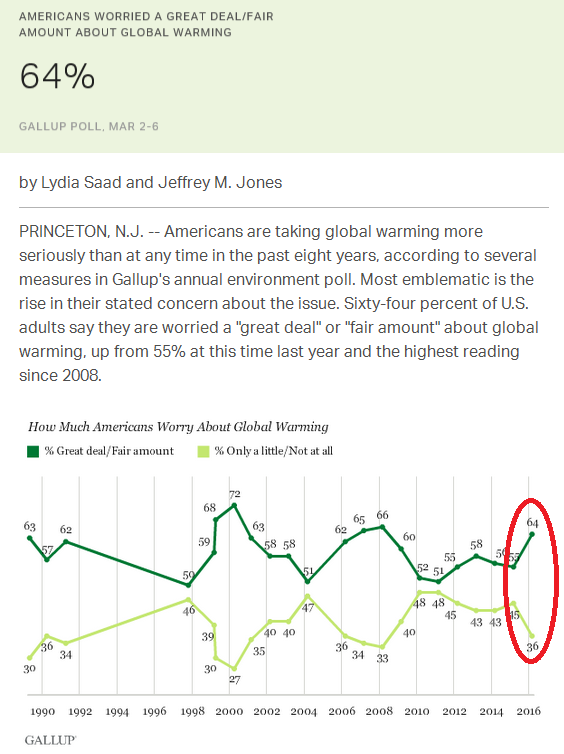

Other results from the 2016 Gallup poll are equally striking. They show a record-high share of Americans stating that climate change poses a threat to them and their way of life; a record number agreeing that climate change is caused primarily by human activity; and climate concern climbing across the political spectrum.

Other results from the 2016 Gallup poll are equally striking. They show a record-high share of Americans stating that climate change poses a threat to them and their way of life; a record number agreeing that climate change is caused primarily by human activity; and climate concern climbing across the political spectrum.

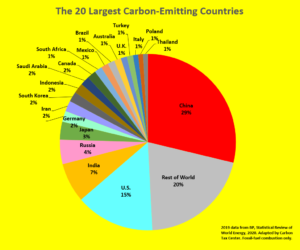

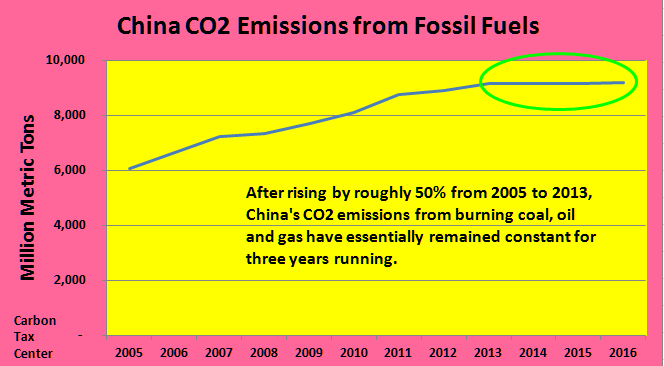

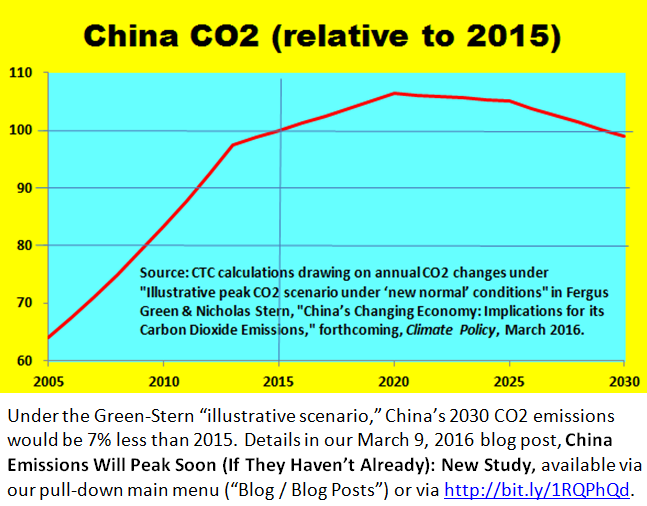

Even more strikingly, a paper published in March 2016 in Climate Policy forecasted that China’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion might peak as early as 2020 — a full decade before the cap target year. Moreover, rather than shooting past earlier benchmarks, emissions in 2030 would be 7% below the 2020 peak and even 1% under 2016 emissions, according to the Climate Policy forecast. Such a turnaround would exceed all but the most buoyant expectations that greeted the 2014 announcement and would raise the bar for the U.S. and the other 190 nations that submitted emission pledges at the U.N. climate summit in Paris in December.

Even more strikingly, a paper published in March 2016 in Climate Policy forecasted that China’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion might peak as early as 2020 — a full decade before the cap target year. Moreover, rather than shooting past earlier benchmarks, emissions in 2030 would be 7% below the 2020 peak and even 1% under 2016 emissions, according to the Climate Policy forecast. Such a turnaround would exceed all but the most buoyant expectations that greeted the 2014 announcement and would raise the bar for the U.S. and the other 190 nations that submitted emission pledges at the U.N. climate summit in Paris in December.

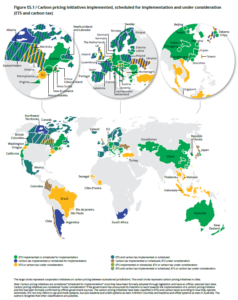

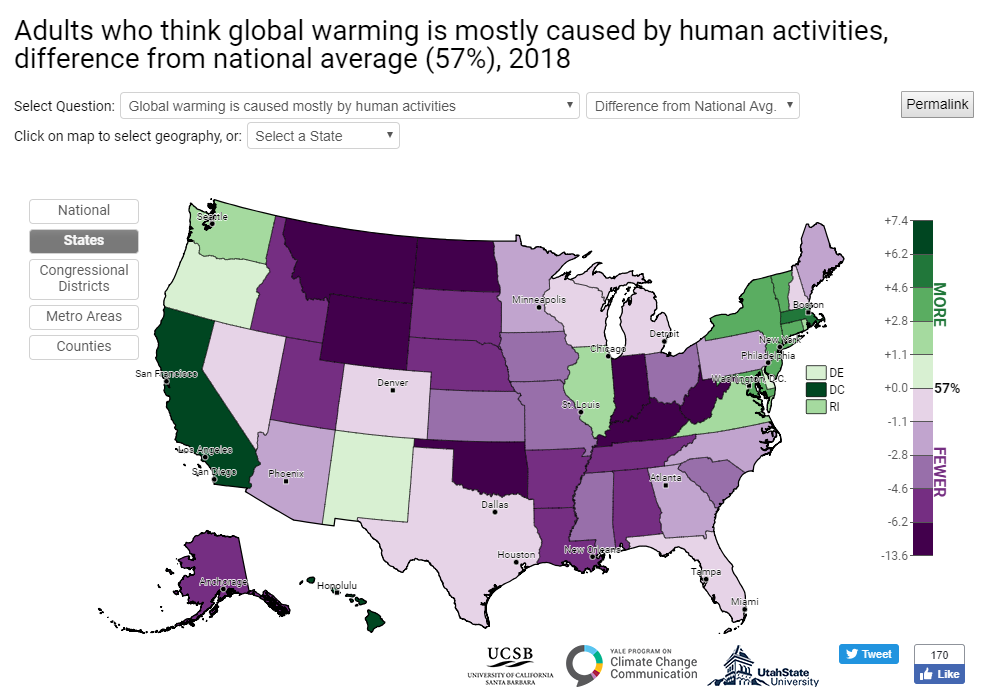

The map above is just one of several hundred that may be viewed and downloaded from the

The map above is just one of several hundred that may be viewed and downloaded from the

, in March 2016, nearly two-thirds (64%) of American adults told Gallup’s annual environmental poll that they were worried a “great deal” or a “fair amount” about global warming. That figure was up from 55% in March 2015 and was the highest reading since 2008,

, in March 2016, nearly two-thirds (64%) of American adults told Gallup’s annual environmental poll that they were worried a “great deal” or a “fair amount” about global warming. That figure was up from 55% in March 2015 and was the highest reading since 2008,