Defending NY’s Congestion Pricing Program

This post first appeared in The Washington Spectator, which posted it yesterday, Feb. 19. We’ve edited it slightly: swapping in a more finely-grained pie chart of trips to the zone by mode, adding a Hochul-vs-Trump graphic, and substituting excerpts from and a link to Gov. Hochul’s Grand Central Station press conference in place of an earlier quote from Reinvent Albany head John Kaehny. The remaining content is the same.

— C.K., Feb. 20, 2024

So much winning. Unjammed bridges and tunnels. Speedier deliveries. On-time buses. Calmer, more inviting streets. Fewer traffic crashes. Repairmen getting to more jobs.

Not Donald Trump’s kind of winning, however. Trump didn’t invent congestion pricing. A Nobel economist — a Canadian, at that — worked out the theory 60 years ago, and a ragtag crew of transit lovers, car inquisitors and dyed-in-the-wool urbanists spent decades importuning New York’s political establishment to put it into practice.

The president had nothing to do with the toll plan. In fact, everything about it screams woke — or does to troglodytes too blinkered to see that congestion pricing’s biggest beneficiaries are motorists, who daily reap substantial dividends in saved travel time.

So it came as no surprise that today Trump’s transportation secretary Sean Duffy told NY Gov. Kathy Hochul that the president intends to rescind federal approvals and to terminate the toll program, which went into effect in early January.

Fortunately, officials at the state-chartered Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which operates the city’s buses, subways and major bridges, and was invested half-a-dozen years ago with legal authority to administer the congestion pricing program, were ready. Mere minutes after Duffy’s announcement, the MTA filed a 51-page complaint in federal court charging Duffy, U.S. DOT and the Federal Highway Administration with usurping their statutory authority and seeking to bar them from interfering with the tolls.

Ozempic for Cities

“Am I tripping?,” shock jock Kai Cenat asked on Hot-97 last month. “Congestion pricing might actually be working.” Self-styled housing advocate YIMBYLAND pointed to plummeting subway crime and dubbed congestion pricing “the Ozempic of urbanism,” musing, “I wonder what else it can fix.”

Congestion pricing’s success at cutting traffic is winning converts.

The answer is: quite a lot. The unmistakable takeaway thus far is that just a few fewer cars goes a long way. The drop in the number of vehicles driven into the toll zone is probably 10 percent tops (conclusive data isn’t out yet). But it feels like more. In the papers and on TV, drivers are reporting less time stuck in their cars. In a recent poll, habitual car commuters to Manhattan strongly backed congestion pricing.

The “stick” that has dialed down traffic’s manifold negatives is actually fairly modest — a $9 toll to drive into Manhattan south of 60th Street. Compare that to my calculation that a median car commute to and from the congestion zone slows down the other cars, trucks and buses in its gravitational field by an aggregate of minutes and seconds that equate to $100 worth of lost time. As the toll “carrot” kicks in, in the form of $15 billion worth of transit improvements that the toll revenues will bond, subway travel will get better and safer, helping shrink car use even more.

To be sure, traffic will rebound somewhat as drivers feel the allure of less-clogged roads. But unlike traffic cops or synchronous traffic lights or other traffic-taming nostrums perennially attempted in New York and other U.S. cities, congestion pricing will yield a durable drop in traffic. Sure, call it a miracle. I have. But the eased traffic is the predictable product of pricing “congestion causation” into car trips that collectively create traffic jams.

The Serpentine Road to Jan. 5

What looks straightforward in print was, in practice, anything but. In Diary of a Transit Miracle, published in The Washington Spectator last April, I traced the 50-year effort to define, scope, build support for, and legislate New York congestion pricing. The miracle, I wrote, was three-fold: “Winners will far outnumber losers; New York will be made healthier, calmer and more prosperous; and that this salutary measure is happening at all, after a half-century of setbacks.”

Soon enough, the triumphant odyssey was torpedoed in the bow. On June 5, Gov. Kathy Hochul, whose office has authority over the MTA and, thus, over congestion pricing, peremptorily and indefinitely “paused” its June 30 start — a perfidy I dissected in Hochul Murder Mystery. The outbreak of pro-congestion pricing support would persist, I predicted, returning the governor to the fold — as happened in November, after the election. Congestion pricing would go into effect on Jan. 5, though scaled back from the June 30 rates. The intended $15 peak toll was lowered to $9, with truck tolls and taxi and Uber surcharges reduced by 40 percent as well.

Congestion pricing supporters at Lexington Ave. and 60th Street, 12:03 a.m. Jan. 5, 2025. I’m at center, foreground, holding yellow sign and chatting with journalist-author Christopher Ketcham. Tall man smiling at right is Rit Aggarwala, who led Mayor Bloomberg’s 2007-2008 bid to enact congestion pricing and now heads the city’s Dept of Environmental Protection. Photo: Sproule Love.

Even diminished, congestion pricing promised much for New York — especially if Hochul or a successor adhered to her pledge to raise the toll to $12 in 2028 and, in 2031, to the full $15. Toll supporters gladly took the win. As midnight approached on Jan. 4, we thronged Lexington Avenue and 60th Street, braving the midnight cold to count down the final seconds of life without congestion pricing.

We were festive and appreciative. “NY ♥s drivers who pay,” read my sign. “Thank you for paying the toll,” said another. “You’re making history!,” proclaimed a third. No one asked if “you” denoted the crowd, or the drivers whizzing by, or our fair city. For a bright, shining hour, it was everyone.

Why Trump Wants to Eradicate Congestion Pricing

Once upon a time, a wannabe developer looking to make a mark in Manhattan might have bet on congestion pricing. Wharton might have schooled him that prices beat queues at sorting supply and demand. He might have paid notice in the 1980s as true-life real estate titan Dick Ravitch used his pulpit as MTA honcho to hammer home that a thriving Gotham required functional transit, which in turn required robust new revenue streams. Throughout Mike Bloomberg’s mayoralty, he might have listened as Kathy Wylde, chief of the blue-ribbon business group Partnership for New York City, repeatedly decried region-wide traffic gridlock as a $20 billion a year tax on residents and businesses.

Meanwhile, of course, Donald Trump did none of those things. From time to time he fulminated against congestion pricing, though more as a nuisance like, say, water-saving flush toilets. As president he escalated his rhetoric. In a Feb. 8 interview with the New York Post, Trump called the tolls “horrible” and “destructive to New York.” Ignoring mounting evidence like January’s big year-on-year uptick in attendance at Broadway shows, he dismissed the reductions in traffic jams, rationalizing that “Traffic is way down because people can’t come into Manhattan and it’s only going to get worse.”

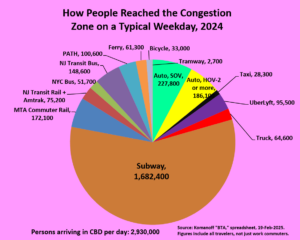

That’s your standard “windshield perspective” at work, oblivious to the reality that barely one-fifth of folks coming to the Manhattan congestion zone arrived in a private vehicle prior to congestion pricing. (See chart.) True enough, a few days after Trump’s Post interview, local news sources reported a rise in Manhattan foot traffic in congestion pricing’s first month compared to the year before.

Pre-tolling, only one-fifth of person-trips to the congestion zone were via private vehicle; among regular work-commuters the share was even smaller.

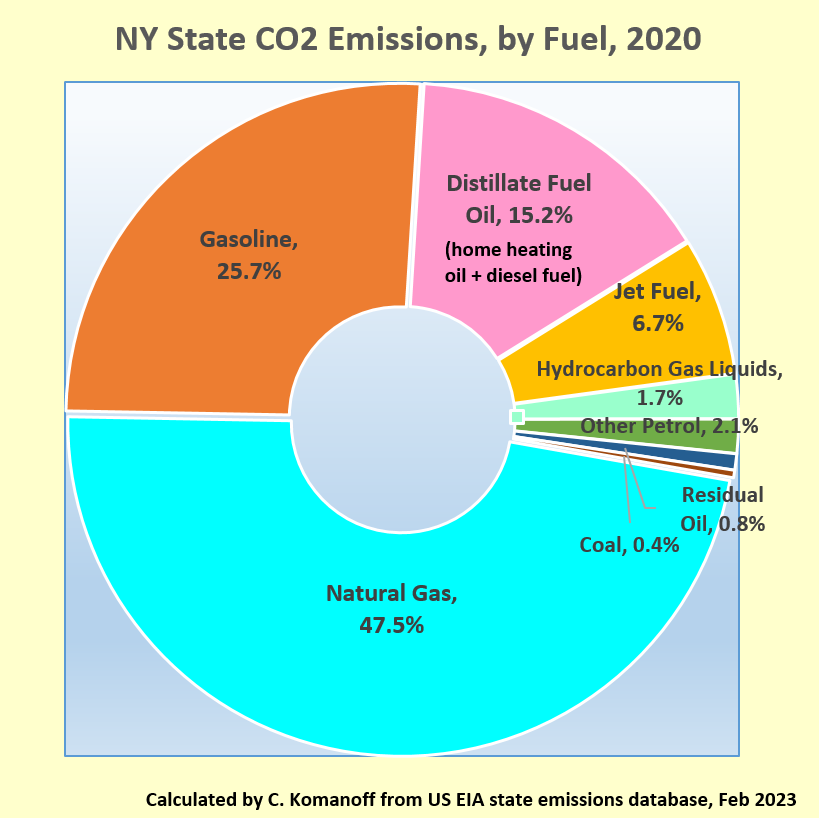

Still, the Trumpian brain gazing at congestion pricing sees not a respite from traffic gridlock but oil barons’ birthright squandered on mass transit and climate. Ironically, the tolls’ direct hit to petroleum and carbon will be relatively modest; by design, congestion pricing applies just to a sliver of city driving.

If congestion pricing had a motto, it would be, “Don’t ban cars, bill them” —a mantra lost on The New York Times, which today wrote> that the tolls “aimed to discourage drivers from entering the congestion zone.” Wrong. Congestion pricing seeks to dissuade a smallish fraction of drivers — 10 to 20 percent — from doing so. The other 80 to 90 percent are meant to keep driving to ensure sufficient toll revenues to bond the promised transit investments.

Subtle truths be damned, congestion tolling is anathema to Trumpworld, where policy considerations are buried under monstrous simplification, crude disinformation, coarse slander and, most often, outright lies. Congestion pricing’s crime is that it elevates the collective interest above individual actions that threaten it. It requires drivers to Manhattan’s teeming center to either change their behavior for the common good of congestion reduction, as Paul Krugman put it recently, or to offset some of the harms from their driving by paying into a government-administered kitty — to be invested in transit betterment that will reducing congestion further.

Krugman conjectured that “hostility to New York” may be the true font of Trump’s antipathy to congestion pricing. “Many people, and Trump in particular,” Krugman wrote, “are committed to the view that [New York] is an urban hellscape. A policy that improves life in the city runs counter to that narrative and inspires visceral opposition. And Trump in particular surely wants to hurt a city that has never supported him.”

A balm for New York, if we can keep it

It’s easy to be gloomy about congestion pricing’s ability to overcome Trump’s enmity. Even if the MTA prevails over Secretary Duffy in federal court — and the Authority appears to have a strong hand — the Trump administration has myriad ways to coerce New York State into ending the program. It could slow Federal Transit Administration reimbursements to the MTA for expenditures already authorized and made. Going forward, Trump could constrict routine federal contracts to rehabilitate and build new transit. The rational choice for the state and MTA might then be to give up the toll program.

Or, Trump could hold that power in reserve as leverage to get New York City and State to fall in line or not make waves on a hundred other fronts. Not selling out congestion pricing requires Gov. Hochul to be steadfast and for Mayor Eric Adams, who began distancing himself from the tolls long before bending his knee to Trump, to leave or lose his mayoralty to a congestion pricing defender.

Hochul, for her part, is off to a rousing start. Addressing congestion pricing supporters at NY’s Grand Central Station yesterday, she said:

At 1:58 pm, President Trump tweeted, ‘Long live the king.’ I am here to say that New York hasn’t labored under a king in 250 years and we are sure as hell not going to start now… We stood up to a king and we won then. In case you do not know New Yorkers, we’re in a fight, we do not back down — not now not ever… I don’t care if you love congestion pricing or hate it, this is an attack on our sovereignty, our independence, from Washington. We are a nation of states. We are not subservient to a king or anyone else from Washington… We will not [let] the commuters of our city and our region [become] roadkill on Donald Trump’s revenge tour against New York.

But to feel the governor’s steely determination to keep congestion pricing, it’s best to hear her. This 20-minute YouTube video of her and MTA chief Janno Lieber leaves no doubt that she is more than ready to go to the mat with Trump. She sounds positively liberated.

“King” Trump vs. Gov. Hochul. Diptych courtesy of Ryder Kessler, Abundance New York.

Of one thing we can be sure: For Hochul to maintain her brave stance will require continued, sustained organizing — more of the grinding work that brought congestion pricing to life in the first place. The old saw about genius being 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration applies here.

In this trilogy’s first installment, I gave pride of place to congestion pricing theorist Bill Vickrey. So did the Times’ “Big City” columnist, in an encomium to the Nobel economist last month that implicitly treated the unceasing toil of congestion pricing’s legions of supporters over the years like so many dust bunnies.

But the Jan. 5 victory belongs not just to Vickrey and Ravitch and Wylde, or to Lieber and his relentless staff, but also to Riders Alliance, Reinvent Albany, Regional Plan Association, the Community Service Society, a revitalized Transportation Alternatives, and scores of allied organizations and associations that together coalesced into a civic force for municipal progress, good governance and improvements in our quality of life. And to the journalists who gave our labors prominence.

These organizations internalized and acted on the twin beliefs that having too many cars hurts cities, and that traffic pricing is indispensable for diminishing the automobile’s stranglehold over transportation budgets and road designs. After Hochul’s congestion pricing “pause” last June, they rose as one to block her ploy to concoct a substitute transit funding source. “We never considered it, not for a minute,” Riders Alliance senior organizer Danna Dennis told me earlier this month. “It was congestion pricing all the way.” Likewise for Liz Krueger, state senator from Manhattan’s east side, who rallied her Albany colleagues to render the governor’s gambit dead on arrival.

The result, on Jan. 5, was an epic breakthrough. For the first time in the USA, driving is being assessed a charge for some of the immense harms it wreaks on urban life. At this writing, 45 days on, the facts on the ground are everything that congestion pricing proponents dreamed of and promised. Every new day that dawns with the tolls intact puts the lie to the claims of Trump’s minions that the program is hurting New York. Sure, like Ozempic hurts the chronically obese.

It can feel unfair to have to keep on defending a program that has the force of law and is working wonders. But we must and we will.

Another venue ripe for cost internalization: NYC food delivery

This post was published earlier today by the New York livable-streets site Streetsblog, under the headline Reining in Deliverista Distances is the Key to Safety. I’ve cross-posted it here because the proposal it conveys — a per-mile charge on app-based food deliveries — is an easily understandable illustration of the principle of “cost internalization” embodied by carbon taxing. Other recent illustrations are Strawberry Yields Forever, which reported on a grower-backed tax on groundwater in California’s Pajaro Valley; A Tantalizing New Front in Externality Pricing, about a proposed tax on helicopter noise; and periodic posts on the twists and turns in the long campaign to implement congestion pricing in New York City (here and here).

The text here duplicates the expositon in Streetsblog but near the end adds a paragraph contesting the widespread presumption that externality pricing necessarily injures marginalized groups (environmental justice communities, in the case of carbon pricing; food-delivery riders, in the case of the mileage charge outlined here).

— C.K., Nov 5, 2024.

Food deliveries in New York are spanning ever-longer distances. Before food apps, and before motorized bikes, deliveries came from nearby — from the local pizza parlor or neighborhood joint. Now deliveristas can be seen traversing the East River bridges or blasting up the Hudson River Greenway and the Central Park drives. When I ask a delivery rider at a red light how far he’s going, it’s often much more than a mile.

I’ll say it out loud: All that DMT — Deliverista Miles Traveled — has become a drag on other city cycling. It’s made the streets more chaotic and is stressing our bicycle lanes. Routine cycling maneuvers like sliding over in the bike lane or turning now require constant signaling and checking to avoid getting clocked from behind.

Photo: Josh Katz. Photo montage: Streetsblog.

Cars and trucks remain the greater danger, of course. But I find lumbering vehicles easier to anticipate and navigate around than darting mopeds or e-bikes. No, I’m not giving up cycling, but I’ve lost count of how many acquaintances have. The need for vigilance and the fear of being taken down in a crash became too great.

What the Comptroller Missed

City Comptroller Brad Lander last week issued a report, Strategic Plan for Street Safety in the Era of Micromobility, aimed at safeguarding workers and minimizing dangers to the public from the food-delivery industry.

As Streetsblog reported, Lander wants the city to exert authority over app companies like DoorDash and Uber Eats that process 90 percent or more of food deliveries in the five boroughs.

His suite of reforms is a start, especially jawboning officials to throttle the import and use of non-UL e-bike batteries like the ones that have sparked scores of serious fires.

But it misfires in pinning its street-safety aspirations on an empowered workforce and a semblance of enforcement by NYPD. The first can only go so far. The second appears to be a pipe dream. Lander also failed to include the lowest-hanging fruit for food-delivery safety: reining in deliverista miles traveled.

Reduce ‘Deliverista Miles Traveled’

Picture 40 percent of citywide food-delivery e-bike and moped miles eliminated. This would greatly enhance everyone’s safety, not just by directly cutting the sheer amount of fast and sometimes startling two-wheeling but also by dialing down street chaos and helping other cycling regain a footing in bike lanes and general traffic.

So how would that be accomplished? Mathematically, by shaving a mile from current deliveries covering a mile or more

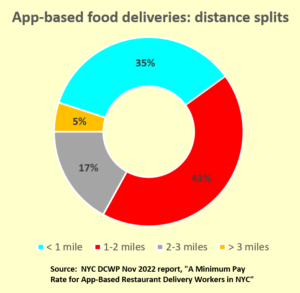

According to a 2022 report from the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection, nearly two-thirds of the city’s app-based food-deliveries exceed one mile. (And nearly one-quarter of all deliveries extend for two miles or more.) Trimming a mile from those deliveries would reduce average delivery distances to 0.85 miles from the current 1.50 — a 43-percent reduction that I round down to 40 percent.

Nearly two-thirds of app-based food deliveries in New York City cover more than one mile, according to city data.

How can we make this shrinkage come about? By taxing app-based food deliveries for each mile beyond an initial free mile — as I outlined over a year-and-a-half ago in the Streetsblog piece, “Want Safe Batteries? Stop Pretending Food Delivery is Free.” The dollar-per-extra-mile fee would be doubled in Manhattan south of 60th Street, where food choices are abundant and foot traffic and road congestion are heaviest. The charges would be paid to the city by the app companies, who would tack it on the bill — creating an incentive for customers to order from eateries closer to home.

I can’t say conclusively that my dollar charge will bring about the envisioned 40-percent mileage reduction. I can confidently predict traffic reduction from congestion pricing because there is so much data about car trips, but food-delivery mileage charging is uncharted territory. The dollar charge for deliveries over a mile might have to be higher, or perhaps could be lower, but we’ll only know if the city conducts surveys or a simulation with randomly selected families spending down pre-filled accounts.

What I can say with confidence is that the delivery mileage charge would generate a ton of revenue — perhaps not my earlier estimated $100 million a year, but close to it. This pot could pay to swap out unsafe batteries and establish deliverista hubs. Some of these endeavors are already under way, happily, and the Comptroller’s plan would move things along, though on the taxpayer’s dime.

(Don’t) Walk on the Demand Side

The omission of a delivery-mileage charge from Lander’s report is a huge missed opportunity, but it wasn’t surprising. New York City’s leading cycling advocacy group, Transportation Alternatives, has yet to mention the idea in its policy papers. Perhaps in striving for solidarity with deliveristas, TA has short-shrifted the concerns of non-commercial cyclists — as Michele Herman, lead author of TA’s classic Bicycle Blueprint (PDF), argued this year in the Village Sun.

Lander’s omission also mirrors the tendency in environmentalist circles to turn a blind eye to the consumption aspect of so many policy questions. Climate protesters picket at banks that they say enable drilling and pipelines, but not at the gas stations at which motorists dutifully fill Big Oil’s coffers or at showrooms pimping the machines that actually combust the petrol. Similarly, the decade-long project to divest pension funds and universities from fossil fuels didn’t cut carbon extraction and burning one iota. It did, however, divert “YIMBY” activism that is vital to New York and other inherently low-carbon cities.

Climate may seem gargantuan vis-a-vis food delivery, but the parallels are powerful. Both spheres treat “demand” as inviolate. Just as suburban households are allowed McMansions and fleets of SUVs, we city dwellers are unquestioned on our right to order meals and treats anytime from anywhere.

Externality pricing is sidelined in both spheres as well. Just as carbon taxes would crush demand for coal, oil and gas, a dinner-delivery mileage charge would help rebalance ordering from faraway to nearby, adding a measure of predictability and orderliness — hence, safety — to city streets, far more than policing could ever do. Yet internalizing even a sliver of an activity’s harms into its price is out of bounds in contemporary discourse. Congestion pricing, whose supposedly “too high” $15 toll would have only offset one-sixth of a car trip’s congestion causation cost, got shelved lest drivers flip out.

And let’s not overlook the diktat granting veto power to potentially afflicted outgroups. In carbon pricing, those are primarily environmental justice communities deemed threatened by carbon emissions charging, even though economic mitigations are readily available and EJ communities suffer the greatest damage from extreme heat, flooding and other climate-wrought disasters.

Delivery-mileage pricing would directly affect the city’s 65,000 deliveristas, of course, but perhaps not adversely. Diminishing deliverista miles traveled wouldn’t equally diminish their employment and wages, since total deliveries would be largely unchanged. What would almost certainly fall is the terrible annual toll of a dozen or more fatal on-the-job crashes.

No sector of labor (or business) in New York City should be held sacrosanct. All should be governed for the greater good. Food delivery regulation should advance social safety without infringing on worker power. A mileage fee on food deliveries can serve workers as well as the society of which they’re a part. What are we waiting for?

What Price Giant Wind?

Belief that bigger is better — or, at least, a lot cheaper — helped sideline nuclear power. It now imperils wind power.

In July, at the first commercial-size U.S. wind farm under construction, near Martha’s Vineyard, a turbine blade split apart and fell into the Atlantic. In May and again in August, at the new Dogger Bank wind farm 80 miles east of England, blades broke off their towers and slammed into in the North Sea.

All three failures involved a mammoth new wind turbine design from GE Vernova, optimized to abundant offshore winds. The 13-megawatt turbines, dubbed Haliade-X by GE Vernova, a spinoff from the old General Electric conglomerate, are the world’s largest, and are nearly four times more powerful than the average wind turbine installed in the U.S. last year, and a full order of magnitude (10x) beyond typical windpower machines installed 20 years ago, according to U.S. Department of Energy data.

Photo of Vineyard Wind farm by Randi Baird. This image led the Sept 12, 2024 NY Times business section.

To be sure, dozens of other turbines at both wind farms are operating trouble-free and helping displace fossil-fuel generation, although the Vineyard Wind farm is now shut. The expected output of each 13-MW unit, 56 million kilowatt-hours a year, will let power grids pull back on incumbent fossil-fuel power plants that would otherwise spew 25,000 tons a year of climate-disrupting CO2, while maintaining wind energy’s meteoric growth. In Great Britain, wind turbines now stand neck-and-neck with power plants burning “natural” (methane) gas as the top electricity source, providing a third of Britain’s electric generation in the first quarter of 2024, according to Energy Advice Hub. In the U.S., although wind power’s kilowatt-hour production fell by 2 percent in 2023 — the first year-on-year slip this century — wind turbines are producing 40 times more electricity than two decades earlier and now account for 10 percent of the nation’s electricity generation.

Despite, or perhaps because of, wind power’s growing prominence, the concatenation of the three incidents is worrisome. The Vineyard breakage seemed to validate the fears of East Coast commercial fishers and other objectors to the large-scale offshore windpower development that has become a linchpin of regional and national drawdowns from fossil fuels. “Jagged pieces of fiberglass and other materials from the shattered blade drifted with the tide, forcing officials to close beaches on Nantucket,” the New York Times reported this week.

Indeed, the Times headlined its story on the Vineyard mishap, “Broken Blades, Angry Fishermen and Rising Costs Slow Offshore Wind,” adding the subhead, “Accidents involving blades made by GE Vernova have delayed projects off the coasts of Massachusetts and England and could imperil climate goals.”

What happened?

Why the blades broke apart isn’t yet clear. According to the Times’ story, GE Vernova has labeled the three incidents “one-offs rather than systemic flaws … but has provided few details about their causes.” The first failure at Dogger Bank, in May, resulted from “an error during installation,” a company spokesperson told the paper, while the second, in August, “happened because a turbine was left in a ‘fixed position’ during a storm.” Trade publication Maritime Executive reported that GE Vernova told investors that the Vineyard blade rupture resulted from a “manufacturing deviation” in the bonding of the blade at a Canadian production facility. But the company “declined to confirm any details about the blade[s] that failed at the UK wind farm and if [both] came from the same manufacturing facility,” the publication said.

[On Sept. 20, just hours after we posted this story, GE Vernova said it planned to downsize its offshore wind business with 900 job cuts, many at the company’s turbine factory in Saint Nazaire, France.]

A GE Vernova 13-MW wind turbine blade awaiting shipment offshore, photographed for NY Times by Bob O’Connor. Its weight is almost certainly double and perhaps triple that of conventional 3.3-MW blades.

The cause could be rooted in the sheer size of the blades and, perhaps, the rapidity with which the industry has scaled up. The blades on the Haliade-X offshore wind turbine are 50 percent longer than those on a representative 3.3-MW land-based wind turbine: 220 meters tip-to-tip for the 13-MW model, according to GE Vernova, vs. 148 meters for the 3.3-MW machine, per the U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s 2022 Cost of Wind Energy Review (pdf). The disparity in bulk is probably well over 2 to 1; if the blade shapes are the same, the ratio of their areas would be 1.50 squared, i.e., 2.25 to 1. If the bigger blades are thicker as well, their weight could be triple that of the conventional blades.

It may be that current technology can’t mass-produce such enormous objects to the quality required to withstand the stresses from constant rotation. Even slight manufacturing defects that smaller turbines could handle might be unforgiving for giantic blades.

This isn’t to say that advances in metallurgy, material bonding and non-destructive testing couldn’t restore reliability for giant wind turbines in the future. The checkered history of rapid size-scaling in the U.S. nuclear power industry may be instructive.

Boosting reactor sizes proved disastrous in the U.S.

Throughout U.S. nuclear power’s “bandwagon era” — circa 1957-1974 — the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and reactor manufacturers subscribed to the idea that nuclear costs would enjoy pronounced economies of scale. Their rule of thumb was that any doubling of reactor capacities — from 100 to 200 megawatts (for so-called “pilot” plants) and, later, from 500 to 1,000 MW — should raise costs only around 50 percent, tantamount to a 25 reduction in per-kW costs.

(The 50 percent cost rise would equate to a factor multiple of 1.50. Dividing that by two, for the doubling in megawatts, would yield a per-kW cost multiple of 0.75, i.e., a 25 percent drop.)

This impressive scale-economy made sense — on paper. Costs tend to track equipment surface areas, while capacity is proportional to reactor volume, portending only a 60 percent rise in costs per doubling of capacity. (Mathematically, two raised to the two-thirds power is roughly 1.6. Why two-thirds? Because surface area rises with the square of length while volume rises with the cube.) This would dictate a 20 percent reduction in per-kW costs from doubling plant capacity. Other cost elements like siting, permitting, engineering, and project mangement would, it was thought, display steeper economies, lifting the overall per-kW cost reduction per doubling of capacity to around 25 percent.

This impressive scale-economy made sense — on paper. Costs tend to track equipment surface areas, while capacity is proportional to reactor volume, portending only a 60 percent rise in costs per doubling of capacity. (Mathematically, two raised to the two-thirds power is roughly 1.6. Why two-thirds? Because surface area rises with the square of length while volume rises with the cube.) This would dictate a 20 percent reduction in per-kW costs from doubling plant capacity. Other cost elements like siting, permitting, engineering, and project mangement would, it was thought, display steeper economies, lifting the overall per-kW cost reduction per doubling of capacity to around 25 percent.

These upbeat expectations from reactor upsizing motivated successive doublings in reactor capacities through the 1960s and into the 1970s. The size increases did cut per-kW costs (or, at least, they helped hold back the tide of increased costs to comply with increasingly stringent safety regulations), but with diminishing returns. My own empirical analysis of costs to complete U.S. reactors, published in 1981, found only a 13 percent drop in per-kW costs per doubled reactor size, even when controlling for so-called regulatory creep. That saving was only half as great as the AEC had posited. Worse, larger reactors took far longer to build than smaller ones, which tied up vast amounts of capital, postponed nuclear displacement of fossil-fuel electricity, and spooked investors.

Larger reactors also proved harder to keep in service, their “teething” problems sometimes persisting for decades. That troublesome era is now decidedly in the past. The U.S. nuclear power sector’s average “capacity factor” has climbed steadily from the post-Three Mile Island accident trough of 55-60 percent operability to nearly 90 percent since around 2000. Still, with investor losses, high utility bills and excess carbon emissions, the toll from too quickly upsizing U.S. nuclear power plants proved immense.

A mid-range carbon price would match cost savings from doubling wind turbine sizes

The scale-economy curve for wind power in the graph above isn’t statistically stout, having been extrapolated from a mere two data points for land-based turbines in the NREL Wind Energy Cost report referenced earlier. (Readers with additional data: please share it with us!) That said, it conveys a message: double the size of an individual wind turbine and the per-kW capital cost should diminish by 18 percent. Factor in greater productivity — I assume that each kW of capacity of the larger turbine produces 9 percent more kWh’s than the smaller one — and the overall cost per kWh of wind power (“levelized cost of electricity,” in industry parlance) falls by 25 percent with a doubling of the turbine’s megawatt size.

That’s no small saving for supersizing, though of course it requires that projects employing the extra-large turbines actually come to fruition. According to the most recent (Aug. 19) Nantucket Town and County 2024 Turbine Blade Crisis Updates page — the name alone is a telling indicator — all installation and operation of turbine blades for the Vineyard Wind project are on hold, though placement of towers and nacelles (the equipment-bearing structures topping each tower) is permitted.

For Vineyard Wind, then, and perhaps for the Dogger Bank project as well, paper savings from going large have become a cruel joke, at least for the time being. Putting that aside, I’ve calculated the theoretical carbon price that would raise the sale price of wind electricity by the same amount that a halving of turbine capacity raised its all-in cost. Rephrased as a question: How big of a carbon price would have to be baked into the cost of prevailing fossil-fuel electricity — assumed to be from the mainstay of the U.S. power system, a combined-cycle power plant burning methane gas — to compensate for sticking with prior 6-7 MW sized offshore wind turbines and, thus, foregoing the assumed 25 percent per-kWh cost reduction from doubling turbine sizes to 13 megawatts?

For Vineyard Wind, then, and perhaps for the Dogger Bank project as well, paper savings from going large have become a cruel joke, at least for the time being. Putting that aside, I’ve calculated the theoretical carbon price that would raise the sale price of wind electricity by the same amount that a halving of turbine capacity raised its all-in cost. Rephrased as a question: How big of a carbon price would have to be baked into the cost of prevailing fossil-fuel electricity — assumed to be from the mainstay of the U.S. power system, a combined-cycle power plant burning methane gas — to compensate for sticking with prior 6-7 MW sized offshore wind turbines and, thus, foregoing the assumed 25 percent per-kWh cost reduction from doubling turbine sizes to 13 megawatts?

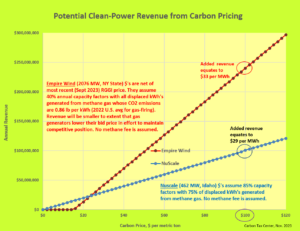

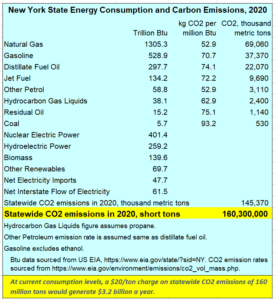

The answer is displayed in the text box at right: $72 per ton of CO2 (equivalently, $80 per metric ton, or tonne; these figures decrease somewhat if we factor in separate methane fees such as the levy enacted as part of the Biden Inflation Reduction Act).

In other words, a $72/ton CO2 price would have given the offshore windpower industry the same profitability enhancement it thought it would reap from doubling its wind turbine megawatt capacities . . . but without the heavy blow rendered by the multiple Haliade-X blade failures.

Granted, there’s no actual link between instituting robust carbon-emissions pricing and easing up on the impulse to push technological advances faster and faster. Even with a $72/ton carbon price, offshore wind turbines would still be in a size race.

The point, rather, is to illustrate the economic power of carbon pricing. If a $72/ton carbon price could raise wind farm profitability by the same degree as a huge and perhaps premature push into bigger frontiers, imagine the leverage that robust carbon pricing could exert on every sphere of economic and physical activity.

‘Hochul Murder Mystery’ Highlights Carbon-Pricing Hurdles

This post, a teeth-clenched corrective to my late-April Diary of a Transit Miracle, was necessitated by Kathy Hochul’s jaw-dropping “indefinite pause” (read: cancellation) of the congestion pricing program she had supported since stepping into the governorship of New York State in August 2021. Like “Diary,” it first appeared in The Washington Spectator, which posted it on June 11 as Hochul Murder Mystery.

That title placed the spotlight on Hochul, whose decision it was to abandon New York City’s congestion pricing plan; on murder, because her delay jeopardizes the precariously perched program to charge drivers to the congested (and transit-rich) heart of the NY metro area a mere fraction of the added travel delays their trips impose; and on mystery, owing to the bizarreness of her abrupt turnabout.

Six days on, however, there’s a growing sense that Hochul simply panicked . . . that her belief in (and grasp of the rationale for) imposing a robust fee on private car trips to the Manhattan central business district was too slender to withstand the criticism from motorists for bringing congestion pricing to fruition.

What’s also growing, though, is the pushback to Hochul’s peremptory, unilateral decision. Not just “the usual suspects” — transit proponents, policy wonks and urbanists — but also business interests, infrastructure contractors and good-government advocates — are mounting a sustained counterattack intended to restore the congestion pricing timeline (it had been on track to “go live” on Sunday, June 30). While that outcome may be out of reach, the final chapter in New York’s congestion pricing saga has not necessarily been written.

Nevertheless, Hochul’s pullback underscores just how hard it remains to bring about meaningful externality pricing in the United States. The high hopes we at Carbon Tax Center had invested in NYC congestion pricing as a pacesetter require that we be candid: the setback to carbon pricing, should it stand, will be considerable.

— C.K., June 17, 2024

Note: Other than the photo montage, which we have reproduced from The Spectator, graphic elements here are new.

Photo montage: Riders Alliance

Not two months ago, in a brief history of how congestion pricing triumphed in New York, I canonized New York Governor Kathy Hochul, placing her alongside transportation legends Bill Vickrey (Nobel-winning traffic theorist), Ted Kheel (transit-finance savant), and the upstart Riders Alliance that in 2019 achieved what previous campaigners could not: legislation mandating a revolutionary new toll system that would weed out enough car trips to Manhattan’s core to cut down on endemic gridlock while generating revenue to enable generational expansions of subway and bus infrastructure.

Diary of a Transit Miracle, the Spectator titled that piece. Hochul, I wrote, had proved herself “a resolute and enthusiastic” congestion pricing backer. “Her spirited support,” I said, “became the decisive ingredient in shepherding congestion pricing to safety.”

Twelve days after announcing her rescission of congestion pricing, Hochul is still being ferociously “dragged” on social media. Another tweet noted that “Hochul’s decision to blow a $15 billion hole in the MTA’s budget [means] she will get blamed for every single mass transit problem going forward in a city where the majority of people take public transit.”

The story, though infuriating to urbanists, climate advocates and foes of big-city car-dominance who for decades had looked to New York congestion pricing for deliverance, is also juicy. It’s hard to recall a public policy story with as many tentacles as this one.

Let us count the ways.

Hochul’s late-in-the-day reversal obviously is a New York story. With congestion pricing, the nation’s largest city, possessor of a singular global brand, was poised to recapture its pre-eminence in progressive, bold innovation. Instead, its literal engine ― its subway system ― has been jilted at the altar.

It’s also a dystopian governance story, as befits the unilateral monkey-wrenching of a policy forged by thousands of individuals, agencies and organizations over years and, for some, decades. As livable-streets journalist Aaron Naparstek wrote on Twitter, Hochul and her Congressional consiglieres “aren’t just undermining congestion pricing, they’re discrediting the Democratic Party and they’re undermining faith in government and democracy.” New York Times editorial writer Mara Gay lamented that “Americans didn’t need a reason to feel more cynical about politics. But Gov. Kathy Hochul of New York has delivered one.”

And of course, it’s a traffic and transit story. How will New York City solve or at least mitigate its habitual, maddening gridlock, which, notwithstanding post-pandemic office malaise, was revealed last week by city transportation officials to have grown even more strangulating than it was in 2019.

Answer: it won’t. Without congestion pricing’s stiff but fair $15 toll to drive into Manhattan south of 60th Street during most hours, alternative measures to reduce New York’s staggeringly costly traffic gridlock will invariably succumb to the dreaded “rebound effect.”

Sign at June 12 rally across from Hochul’s midtown office. An estimated 800 New Yorkers marched for congestion pricing, chanting “Safer streets, cleaner air, Governor Hochul doesn’t care.” Photo by author.

And how will Hochul and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority she commands come up with a billion-dollar-a-year revenue stream to cover the interest on $15 billion in long-awaited investments in subway station elevators, digital train signals, and clean, electric buses?

Answer: they likely won’t. In a chessboard win for congestion pricing proponents, legislative leaders last week refused to rubber-stamp Hochul’s wished-for hike in the Payroll Mobility Tax, leaving her with no means to fund the new transit improvements, and putting at risk thousands of jobs in upstate factories as well as downstate. With congestion pricing the only apparent way to pay for these investments, the resistance stays alive.

Did I say resistance? The widespread pushback to the governor constitutes yet another tentacle to the story. If Hochul thought that protests over her surprise cancellation would peter out, she was badly mistaken. What began as public astonishment quickly turned to upset and grew to outrage, not just for its transit and traffic consequences but for its sheer stupidity (per climate-conscience Bill McKibben) and cowardice and cravenness (per congestion pricing campaigner Alex Matthiessen).

Nor is the rage confined to transit wonks and bike advocates. It is being expressed by the transit construction and engineering companies; by business leaders and real estate interests; by the Daily News’ editorial board as well as the Times’; by the unquenchable Families for Safe Streets who since 2018 have put their bodies on the line to spare future bereaved mothers; by urbanists who hoped other cities would follow in New York’s footsteps; and by “supply side progressives” desperate for America to actually address urban and suburban gridlock as well as housing and climate.

The fury at the governor shows no signs of abating. Midway through writing this article I attended a Riders Alliance protest in East New York where Hochul was derided as Congestion Kathy and Governor Gridlock and her face photoshopped on a faux Daily News headline, “Hochul to City: Drop Dead. Gov. Betrays Millions of Riders.” Every hour, it seems, brings word of a new demonstration, another rally, another elected official and civic leader resolving to harass and if need be break Kathy Hochul to put congestion pricing back on track.

Hochul’s action is also a car culture story. Though the city’s car-besieged and transit-rich Manhattan core is perfectly suited for congestion pricing, New York remains part of the United States and thus under the sway of mercenary auto and oil interests. Many of the city’s long-immiserated straphangers, moreover, aspire to car ownership and bristle over tolls they might someday pay, even though few working-class residents of Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island or the Bronx routinely motor to the congestion zone. Perhaps that is why the subway improvements that the tolls would pay for have yet to resonate with most “everyday” New Yorkers.

The distemper over the governor’s last-minute cancellation isn’t subsiding.

As well, New York’s political class is subway-avoidant and car-besotted, making them kissing cousins to suburban interests whose car windshields render them immune to transit’s value, except perhaps to keep others from clogging “their” road space. That the political ramifications eluded Gov. Hochul only adds spice to the story. That Manhattan and New York City as a whole couldn’t, last week, defy America’s “dominant car culture,” as the Times wrote in its Saturday editorial, is yet another sad aspect of the story.

We come now to the biggest and most puzzling piece of the Hochul congestion pricing saga: Why did she do it?

Why, after uttering nary a negative word about congestion pricing in her thousand days as governor, did she fold with a mere 25 days to go? Why, after extolling congestion pricing repeatedly and evincing genuine pleasure in being its tribune, did the governor move to murder it?

The standard explanation is that key national Democrats, most notably Brooklyn Congressmember and House Speaker-in-waiting Hakeem Jeffries, and perhaps senior White House officials as well, ordered Hochul to ice the June 30 launch to tamp voter defections in borderline House districts. This account is plausible if misguided, given that the four-month interval from June 30 to November 5 afforded ample time to “reset the default,” as Stockholm showed after its 2007 plunge into congestion pricing. The toll’s ostensible unpopularity would have ended up in the proverbial rearview mirror.

Yet these electoral concerns don’t fully add up. Any politician worth their salt knows not to abruptly reverse course on hot-button issues. And while altered circumstances can justify altered policies, no substantive change suddenly roiled New York’s transportation patterns, transit needs or economic vulnerabilities. Indeed, the governor’s fumbling attempts at justification have convinced no one.

Perhaps Hochul, an upstater and baby-boomer, was too ensnared in car culture to believe her own congestion pricing rhetoric. Perhaps campaign cash from automobile dealers moved her needle. Maybe she panicked and lost the words to tell Jeffries that helping him would destroy her political viability, end of conversation.

NYC Comptroller Brad Lander, a staunch supporter of congestion pricing, at a June 12 rally opposite City Hall, announcing litigation to invalidate Hochul’s tolling cancellation. Photo: Dave Colon, Streetsblog NYC.

Whatever caused Hochul to abandon congestion pricing, her blunder is of spectacular proportions, or so it appears to this city dweller. The prospective upset to drivers ― and not all drivers, insofar as some regarded the tolls as a means to speed their commutes ― seems almost quaint next to the actual rage of toll proponents and the derision from much of the public.

The governor can still right the ship. She could offer to lighten the toll burden around the edges, as I outlined last week. She could propose a June 30, 2025 referendum, an idea patterned on Stockholm, although who should be eligible to vote isn’t clear and could become its own bone of contention. She could cite the legislature’s hold on alternative transit funding and admit that Plan A was right all along.

The key word is admit. Not only is congestion pricing made for New York, its prolonged gestation has built it into expectations for transit finance, traffic management and the health of the city that cannot be easily unraveled.

Whatever precipitated Gov. Hochul’s loss of nerve, and whatever the consequences for her governorship and her remaining time in politics, she must reinstate congestion pricing. The need is too great, and the story too scandalous, to pretend that congestion pricing will go gentle into its good night.

Will Energy Efficiency Ever Get Its Due?

After all these years and despite so many accomplishments, measures that save energy remain U.S. climate policy’s bastard child.

Even defenders of energy efficiency sell it short. The latest instance was last Friday’s NY Times column, Give Me Laundry Liberty or Give Me Death!, by the paper’s resident polemicist, the economist Paul Krugman.

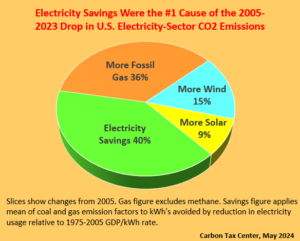

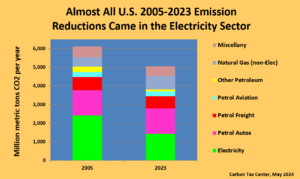

Electricity Savings’ top role in reducing electric-sector emissions is especially critical because no other sector (transport, industry, etc.) cut emissions more than marginally.

Krugman rightly savaged Congressional Republicans for contesting U.S. Energy Department efficiency standards for washing machines and other major energy-consuming appliances. His column reminds us that today’s G.O.P. never passes up an opportunity to force fossil fuels on the American public.

As Krugman noted, Republicans’ depiction of Democrats as enemies of freedom is exactly backwards: “Regulations ensuring that the appliances on offer are reasonably efficient reduce people’s cognitive burden — you might even say they increase our freedom,” by unshackling consumers from the task of weeding out inefficient (and expensive-to-run) appliances from efficient ones.

But consider what Nobel economics laureate Krugman left out: The only U.S. sector that has cut carbon emissions by more than token amounts since 2005 is electricity, furnishing a whopping 92 percent of the overall drop in emissions in 2023 since 2005. (See bar graph further below.) And energy savings, measured as kilowatt-hours that didn’t need to be generated because electricity savings curbed demand, accounted for 40 percent of those electricity-sector carbon reductions — besting the 36 percent from power generators’ shift from coal to less-carbon-intensive fossil gas, and far surpassing the combined 24% share from growth in wind and solar electricity. (See pie-chart above. Details follow at end of post.)

Why are electricity savings undervalued?

Since 2005, the U.S. economy has grown by 40 percent in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. Yet over the same 18 years, U.S. electricity generation barely budged, rising just 5 percent. That is an immense change from mid-(20th)-century, when electricity usage typically grew each year by 6 or 7 percent, practically doubling every decade. This wrenching apart of electricity growth from economic growth has enabled the increased penetration of fossil gas-fired electricity and the rapid increase in wind and solar electricity to bite deeply into coal-fired power generation rather than simply add to it.

Yet energy savings are downgraded in energy and climate discourse. It’s not hard to see why.

First, energy saving is invisible. There are no ribbon-cuttings for energy-efficient buildings or appliances, no medals for low-energy lifestyles. Super-efficient houses or office buildings occasionally are singled out for praise, but what’s the visual — a low-electricity or gas bill? Or, worse, Jimmy Carter’s White House cardigan, which 1970s media held up for ridicule?

Second, saving energy lacks powerful lobbies. There’s no energy-saving counterpart to the American Gas Association, the American Wind Energy Association, the Solar Energy Industry Association, the National Coal Association, and certainly not the American Petroleum Institute, which was represented at the Mar-a-Lago dinner last week at which ex-president Trump pressed the fossil fuel industry for a billion dollars in campaign contributions. Only the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy and the Natural Resources Defense Council persistently advocate for energy effiicency, and they do so as tech experts and champions of the greater good rather than as arm-twisting lobbyists, and certainly not as bundlers of campaign cash.

Lime-green bars show CO2 emissions from electricity generation. The sole other sector with substantially lower 2023 emissions, “Other” Petroleum, shown in yellow, shrank due to natural gas’s increasing industrial-market share.

Energy efficiency and savings also suffer from a measurement problem. Implicit in measuring their climate contribution is a counterfactual: what would energy requirements and emissions have been without the energy savings?

For this post as well as predecessor posts in 2016 and 2020 I used as a baseline U.S. electricity generation if the 1975-2005 ratio between electricity growth and GDP growth had persisted. I think that was reasonable, but who’s to say? The avoided kWh’s I computed for the pie chart depend on a measuring convention that is subject to argument.

(Note that “offshoring” — the compositional shift of the U.S. economy toward services and away from manufacturing, with imports from China and other Asian countries furnishing the lost production — has also contributed to reducing the link between electricity and domestic economic activity; however, its numerical impact only accounts for a fraction of the flattening of U.S. electricity consumption over the paste two decades.)

Energy Efficiency’s Respect Deficit Is Consequential

Undervaluing energy efficiency means that energy-saving policy measures get short-changed. Efficiency standards for appliances, vehicles and buildings are insufficiently supported, enacted and enforced, leaving them vulnerable to being watered down or blocked altogether.

That’s the obvious part. More consequential is the cultural and political fallout. The short shrift accorded energy savings contributes to downplaying the demand side of energy and climate. This in turn has contributed to the unfortunate narrowcasting of climate advocacy as campaigns to block supply expansions. Measures that would curb consumption get disregarded, even though they are arguably more enduring and effective in curbing climate-damaging emissions than campaigns to halt drilling or pipelines, which largely relocate supply expansions elsewhere.

A major casualty of this narrowcasting is sidelining of carbon pricing as a serious policy contender. That’s not to say that the U.S. would necessarily have robust carbon pricing if energy savings were given their due. Rather, the marginalizing of energy savings and of carbon pricing are mutually reinforcing.

Part of the power of carbon taxing is that it operates on both the demand and supply sides of the fossil-fuel and emissions equation. (Another part is that carbon pricing complements virtually every other emissions-reducing policy or program.) Downgrading the demand aspect of our energy and climate miasma does a disservice to carbon pricing — and our climate.

Calculation Details

Calculations for this post were made in CTC’s carbon-tax model spreadsheet (2.2 MB downloadable Excel file). See Clean Electricity tab and Graphs tab. Pie-chart shares are derived by comparing 2023 and 2005 generation for solar (including distributed solar), wind and fossil gas and applying industry-average CO2 emission factors for coal and gas. Electricity-savings slice was computed by subtracting actual 2023 U.S. electricity generation from hypothetical 2023 generation if the average 1975-2005 ratio between electricity growth and GDP growth had continued through 2023, and then ascribing a per-kWh CO2 emission factor calculated as the mean of gas and coal CO2/kWh.

In crediting electricity with 92% of all 2005-2023 U.S. CO2 reductions (from fossil-fuel burning), I divided electricity-sector reductions of 983 million metric tons (“tonnes”) of CO2 by the total reduction of 1,064 million tonnes. However, the denominator is deflated by including “negative reductions” from passenger vehicles (14 million tonnes) and gas for industry (206). Even removing those sectors from the denominator, electricity accounted for 77% of total gross reductions (983 divided by 1,284). Note that these figures are shown in the Outcomes tab of CTC’s carbon-tax model.

Gainsharing: Carbon Taxes Can Put Clean Energy Back in the Black

Note: This post distills and extends ideas from our Nov. 1 post, The Carbon-Tax Nimby Cure.

From the East Coast to Idaho’s high desert, big green-energy investments are foundering.

Composite of (top) first U.S. SMR complex (NuScale facility, artist’s depiction) and (below) offshore wind farm (Orsted’s UK Hornsea facility). Neither was in line for more than token revenues tied to displaced carbon emissions. Both have been cancelled.

Just in the past week, Danish wind giant Orsted scuttled the 2,248-megawatt Ocean Wind farm it was developing off New Jersey’s Atlantic coast, while NuScale scrapped its planned 462-MW complex of six 77-MW small modular reactors (SMRs) near Idaho Falls.

Both ventures were viewed as door-openers to new forms of large-scale U.S. carbon-free green power. They would have contributed mightily to decarbonizing their respective grids, taking the place of fossil fuel electricity now spewing nearly 4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year.

Their demise, along with dimming prospects for Equinor’s 2,076-MW Empire Wind farm off Long Island, NY, suggest that the vaunted crossover point at which big green-energy investments will come seamlessly to fruition fast and hard enough to rapidly decarbonize our grids is receding.

The 1983 title denoted “hard energy” facilities like giant power stations and LNG terminals. Nowadays it also seems apt for big green-energy projects.

The causes are no mystery: supply bottlenecks, spiraling materials costs, 40-year-high interest rates, Nimby obstruction. Not all of these will necessarily persist, but suddenly the combination looks daunting. Big energy projects, once derided as “brittle” by energy guru Amory Lovins, are rife with negative synergies. Nimbys stretch project schedules and impose punishing interest costs, particularly on big wind farms, a phenomenon we wrote about a week ago in The Carbon-Tax Nimby Cure.

Alas, Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act is not a panacea. IRA incentives primarily lift EV’s, rooftop solar, heat pumps, batteries and factories. By themselves they’re not going to refloat stalled clean power projects. The big push will have to come from somewhere else.

What a Robust Carbon Price Could Do for Green Energy

A robust carbon price could do the trick. Not a token price like RGGI’s $15, which is the per-metric-ton (“tonne”) of CO2 value of the 4Q 2023 permit price in the northeast US Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative electricity generation cap-and-trade program; but $50 or more per tonne of carbon dioxide, preferably $100.

I’ve been calculating how much profit a robust carbon price could inject into clean-energy bottom lines. The numbers are so astounding that I checked and rechecked them. Here’s one: A $100/tonne carbon price in NY would allow Empire Wind to charge an additional $200 million or more each year for its output. How? Because the tax would raise the “bid price” for natural gas-generated electricity, the dominant power source and thus the price-setter on the downstate grid by so much — $30 to $35 per MWh, I estimate — that Empire Wind’s 7.25 million MWh’s a year could extract an additional $240 million in its power purchase agreement with the NY grid operator.

Lots to see here. The dollar figures, including the $/MWh bottom lines, are derived off-screen. Added revenues will be less if gas generators lower their grid prices somewhat, but will be more if the methane fee enacted as part of the 2022 IRA comes into play.

Same goes for NuScale. I estimate that its Idaho SMRs could command an additional $100 million a year (less than for Empire Wind because the project is smaller and not all of its output will replace fossil fuels). This additional value equates to $29 per MWh — nearly the same, coincidentally, as the $31/MWh climb in costs since 2021 that triggered NuScale’s cancellation, according to a report by the anti-nuclear Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

These added payments to clean-energy developers are not “subsidies.” They arise by slashing ongoing subsidies now enjoyed by fossil fuel providers and processors — in this case the methane-gas extractors and the electricity generators that burn the fuel — by subjecting these fuels to carbon pricing. The added payments will come about as the carbon price forces the gas generators to raise their sale price to the grid (to recoup their higher price to purchase the gas), which then creates room for Empire (or NuScale) to raise its prices.

Every cent of the carbon tax revenues will remain fully available for public purposes, whether to support low-income ratepayers, or invest in more clean energy or community remediation, or, our preference at CTC, as “dividend” checks to households. None of it needs to be earmarked to Empire or NuScale for them or other clean-power generators to rebuild their profit margins. The gainsharing comes about through pricing carbon emissions, not disbursing the carbon revenues.

Adios, Nimbys?

The Not In My Back Yard crowd wasn’t an apparent factor in NuScale’s downfall. (“Regulatory creep” was, but that’s a story for another time, not to mention one I dissected 40 years ago for the peer-reviewed journal Nuclear Safety.) But they certainly were for Ocean Wind in NJ and will be in NY if Empire Wind goes down the drain.

But here’s the thing: Not only would the added revenue allowed by the carbon price help return Empire Wind to the black. It would give Equinor, the developer, the wherewithal to spread so much largesse among the residents of Long Beach, LI (my hometown!) that they could subdue the Nimbys who have been able to hold up permitting by spreading scare stories about the routing of the project’s power cables underground. Nimby-ism solved, not by suasion (a fool’s errand) but by motivating the masses in the middle who evidently require more tangible inducements than saving the climate (or their beaches or homes).

Let’s Think Big

Ocean Wind, Empire Wind and NuScale are just a few examples of carbon-free projects that could again pencil out with robust carbon pricing. The question remains, how do we get there?

The point of this new analysis isn’t so much to tie clean energy to carbon pricing, but to enlist the political power and prestige of clean-energy entrepreneurs and developers on the side of carbon-tax advocacy.

As we noted in our previous (Nov. 1) post, during headier carbon-pricing times (2007 to 2011) the Carbon Tax Center attempted, alongside allies like Friends of the Earth, the Friends Committee on National Legislation, and Citizens Climate Lobby, to induce the American Wind Energy Association, the Solar Energy Industry Association and other green-tech trade groups to join us in advocating carbon taxing. We put out similar feelers to the Nuclear Energy Institute and the American Nuclear Energy Council. Getting the U.S. nuke lobby behind carbon taxing should have been a no-brainer, given that carbon taxes that monetized the climate value of nuclear power plants’ combustion-free electricity could have supplied mega-dollars to keep extant reactors solvent.

2010 redux: Equation at left signifying “Renewable Energy cheaper than Fossil Fuels” was a cleantech meme. Button on right, created by then-CTC senior policy analyst James Handley, was less prevalent. Time to meld the two?

No dice. We weren’t granted even one conversation with the nuclear folks. The wind and solar people, for their part, insisted that unending cost reductions through increased scale and efficiency, along with green power’s inherent magical appeal, would propel them past any obstacle. Why besmirch our Randian aura with energy taxes, they seemed to say, when our tech is going to usher in energy abundance and spare earth’s climate?

Things look different now. Big, carbon-free power ventures — the ones that everyone from governors and ambassadors to scientists and schoolkids are counting on to get us off fossil fuels — are beset by troubles: financial, logistical, cultural.

Without genuine carbon pricing that accords clean energy the economic rewards to which it’s entitled, too many large-scale green energy projects are going to come up short. As we asked in that earlier post: Will clean-power developers look at this week’s NJ and Idaho losses, among others, and decide that they need a carbon tax every bit as much as the climate does?

Grounding Helicopter Luxury

Extinction Rebellion takes on heliports in Manhattan during a week of climate action.

This post, written by renowned eco-journalist Christopher Ketcham and commissioned by and published in Truthdig on Sept. 15, describes an action I helped organize and participated in, two days earlier. We repost it here, with permission, because it highlights a rare climate protest that targets fossil fuel “demand” rather than supply. And not just ordinary fuel usage but an egregiously selfish and exclusive one: helicopter travel.

This post, written by renowned eco-journalist Christopher Ketcham and commissioned by and published in Truthdig on Sept. 15, describes an action I helped organize and participated in, two days earlier. We repost it here, with permission, because it highlights a rare climate protest that targets fossil fuel “demand” rather than supply. And not just ordinary fuel usage but an egregiously selfish and exclusive one: helicopter travel.

“Helicopters are a pestilence to New Yorkers and a rotten pinnacle of an economic system that places decadent pleasure over planetary survival,” I declaimed in the XR press release. True externality pricing would shut down the vast majority of helicopter transportation. Absent, or alongside that, last week’s direct action was an attention-getting way of connecting the climate crisis to luxury emissions.

— Charles Komanoff, Sept. 20, 2023.

* * * * * * * *

The Extinction Rebellionists mustered south of the heliport on the west side of Manhattan at around 2 p.m., just as the sun emerged following a flurry of rain. It was hot when the crowd of 40 people moved as one to stop the howling machines based at Blade Lounge West, a commercial heliport on 30th Street along the Hudson River Greenway. The outsized carbon footprint of those who used the heliport was “obscene,” said the organizers. The afternoon’s goal was to make as much trouble for its operations as possible.

One of the organizers of the action, a 75-year-old energy economist named Charles Komanoff, was prepared to be arrested. He told me he had been feeling unsteady that morning, jittery and fearful, as he handed me his rain slicker and water bottle and backpack to hold.

Months earlier, he had explained his reasons for wanting to shut down helicopter traffic in his native city. “New Yorkers hate helicopters,” Komanoff wrote in an email to Extinction Rebellionists:

Tourist helicopters, Hamptons helicopters…. They hate the noise, the fumes… the arrogance, the power to pollute, the power to act as lords. I hate them too, for those reasons, plus this: helicopters epitomize luxury carbon. They are the essence of the consumption that must disappear *now* if we aim to protect Earth and preserve climate.

Now, Komanoff and his fellow Rebellionists picketed at the vehicle entry to the Blade Lounge West, which is owned and operated by Blade Air Mobility, Inc. They unfurled a banner that said LIFE OR DEATH, and waved XR flags that whipped in the wind, and one pushed a stroller with three baby dolls in it, with a note that read, “Will we have enough food to eat? Can crops survive the heat?” They chanted Helicopters, private planes, your emissions are insane. (They are also profitable: Blade Air Mobility’s $61 million in revenue in 2023 was up 71% on the year.)

Komanoff and I had written an editorial together in 2022 about the absolute need to kill luxury emissions as the stuff of gluttony and entitlement. “‘Keep it in the ground’ protesters confine their blockades to energy supply infrastructure and studiously ignore the demand half of the equation,” we wrote. “This has been a shortcoming of the climate movement for too long, as it passes up one opportunity after another to rouse millions against the class that, even more than the corporations of Big Carbon, perpetuates the climate crisis: the world’s wealthy.”

The protest unfolded in the genteel way of these things. There were cyclists and joggers on the greenway, and tourists walking, and in the glint of the sun off the rippling water, many passersby stopped and asked what was happening. Two elderly women wanted to participate. One of the women, 72-year-old Mireille Haboucha, an Egyptian, told the protesters, “We agree with your action. This is what we all need to do.” The friend with whom she was strolling, Barbara Schroder, 75, told me, “We had never thought about luxury emissions, but it makes sense to stop it.”

I asked a 29-year-old lawyer named Dominique why she was there. It was her first climate action, and she asked that her last name not be used. “I’m morally obligated,” she told me. In that feeling of obligation there was great anger. “There are 30 million people in Pakistan homeless because of floods that happened there a year ago. Thirty million that are homeless because people like the assholes we are seeing today need to take helicopters.”

Dominique was reminded of Hannah Arendt’s observation, in “Eichmann in Jerusalem,” a book about the Nuremberg Trials, that complacency seemed to be the main evil which allowed the Holocaust to happen — the world, and especially Germans, just not caring enough to stop the Nazis. “Part of the moral obligation for me is that we are on the brink of, are already in, mass climate genocide,” she told me. “I do not want to be the modern-day equivalent of a complacent 1930s German.”

The night before, at an XR body blockade training event in Brooklyn, a 56-year-old retired schoolteacher told me that, on her farm in Wallkill, in the Hudson Valley, the entire oat crop had failed. First there was drought, in April, then flooding in June. That was one of many reasons she was at the heliport. She’d been arrested seven times since 2019 for similar actions.

The helicopter traffic did not cease, although the protesters succeeded in blockading the entrance to the parking lot. The CEO of Blade Air Mobility, Rob Wiesenthal, a dapper little man who makes $11.9 million a year, seemed shocked that his poor heliport had been targeted. The executive stood and watched the protesters with a look of despair on his face. A chopper came blasting in, touching down with a monstrous flatus sound and carrying with it the stink of jet fuel. Then another and another arrived, their disgorged passengers forced to cut through the crowd of flag wavers and shouters of chants to waiting mammoth SUV taxis that were blocking road traffic because they couldn’t enter the parking lot. (Climate action should involve stopping the SUVs, too, I thought to myself.)

I screamed a question to Wiesenthal over the racket. He smiled and said he had nothing to say to the media on the record. His employees were enraged. One of them got in a scuffle with a press photographer on hand for the event, trying to grab his camera, cursing and threatening him. A scowling heliport attendant named Anthony Smith told me, “I called my boys from uptown and they’re gonna take care of this real quick. You’ll see.”

The skies cleared fully, and the sun blazed down, and the protesters knitted their sweaty brows in the heat. Still they picketed and chanted and sang and hurled slogans. A National Guard helicopter, enormous and looking like a black metal buzzard, swooped in, bathing us in poisonous fumes. “Those your boys?” I asked Smith. “Oh yeah,” he said. But the black chopper touched the tarmac for less than a minute, then powered up again and was gone in a fury of rotor wash and noise. More helicopters came, Hueys from JFK Airport ($225 one way) and Newark International ($245) and the Hamptons ($1,025).

After an hour and a half, 40 or so officers from the New York Police Department’s Strategic Response Group arrived bristling with zip ties. Warnings were issued to cease blocking the way, and some of the protesters — the green and yellow teams, as they were called — stepped aside. The red team, which included Komanoff, a 75-year-old woman named Alice, a 60-year-old woman named Heidi, a third woman, Shoshana, and two young men — stood firm, for their intent was to be arrested in symbolic revolt. The cops turned them around, zip-tied their wrists and off they went in a cramped police van. The protesters dispersed. Wiesenthal breathed relief. His faithful employees bumped fists.

What was accomplished? Morale-boosting, the fostering of solidarity and sense of unity of purpose; the building of a community, ready for more action. When the six arrestees were released from the 7th Precinct, they were smiling and proud, and a group of fellow protesters was waiting for them at a nearby restaurant and filled the place with wild applause as they entered. My thought was this crowd needs to gather on a daily basis at West 30th Street. Pain should be felt over and over at Blade Lounge West until its operations become untenable, until Mr. Wiesenthal’s despair is permanent. It’s either that, or what some in the movement say is the next needed step: monkeywrench the choppers and destroy them on the tarmac.

New York Times congestion-pricing table-setter bodes well for carbon taxing

The New York Times yesterday published my op-ed, There’s Only One Way to Fix New York’s Traffic Gridlock, co-written with Columbia University climate economist Gernot Wagner.

Our essay is a meticulous and extensive (1,300 words) brief for making drivers feel the pocketbook costs of their vehicles’ traffic-jam causation, via the policy measure known as congestion pricing. In our telling, not only is this policy guaranteed to generate immense benefits for New Yorkers; as the title suggests, we declare it to be the only way to “free … drivers from the traffic snarls that pollute the air and crush the soul.”

From the Times’ home page, June 8, 2023.

The essay was nearly a month in the making and the product of extensive argument-shaping and fact-checking by the Times’ op-ed staff, bespeaking the paper’s commitment to presenting congestion pricing in a positive light. Its appearance broke the mold of the paper’s hesitant past coverage in two important respects:

1. It explicitly rests on the “comprehensive spreadsheet model” of New York traffic and transit I began developing in 2007 (coincidentally, the year I launched the Carbon Tax Center).

2. It let Gernot and me voice the inconvenient assertion that the regional transit agency charged with designing and administering congestion pricing — the Metropolitan Transportation Authority — “through a few fateful, faulty assumptions, underestimated drivers’ propensity to switch trips from cars to other transit options.” These flubs have tied congestion pricing advocates in knots, forcing us to rebut objections of environmental justice impacts that don’t stand careful scrutiny, although they understandably resonate with communities that historically have borne hugely disproportionate damages from highways, energy facilities and other polluting infrastructure.

It’s only a modest stretch to view the Times’ twin breaks with tradition as the Grey Lady’s version of Andrew Cuomo’s bombshell announcement in August 2017 that “congestion pricing is an idea whose time has come” — itself a rupture that set in motion passage of the state statute authorizing congestion pricing in March 2019.

They suggest that the Times may be lying in wait for the right political winds to let advocates of carbon pricing make a parallel case with respect to climate. Not that a carbon tax is “the only way to fix America’s carbon crisis” but, rather, that it’s a complementary policy tool to last year’s Inflation Reduction Act, and an essential one to ensure that green energy actually replaces rather than merely supplements use of fossil fuels.

For the benefit of non-subscribers blocked by the Times’ paywall, and also to enable comments as well as add a few graphics, we present Gernot’s and my op-ed in full.

— C.K., June 9, 2023

The plan to charge drivers to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street, which last month moved closer to federal approval, will deliver two notable gifts to New York and the region when it begins, perhaps as soon as next April.

The first is that congestion pricing will cut traffic not just within the so-called charging zone but on the hundreds of streets and highways that cars use to go to and from that zone. This reduction of almost two million miles traveled in the region each day will free many drivers from the traffic snarls that pollute the air and crush the soul.

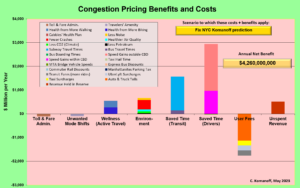

Using a detailed benefit-cost analysis that assumes a pricing structure of $15 at peak times, $10 as traffic begins to thicken and $5 at off-peak times, we calculate that the value of those projected time savings to drivers and truckers amounts to nearly $3 billion a year, with time saved in the boroughs and counties surrounding Manhattan exceeding those on the island.

These estimates are based on a comprehensive spreadsheet model of the region’s traffic, developed by one of us (Mr. Komanoff). State officials used that model to write the statute authorizing congestion pricing, which the New York State Legislature passed in 2019.

The other gift will be the $1 billion a year in congestion pricing revenue that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority will use to secure $15 billion in bonds to pay for improvements to mass transit in the city. Those upgrades will reduce waiting times and onboard delays — and the precious time subway passengers lose as a result.

Either outcome would be a godsend. The combination has the potential to be transformational for New Yorkers.

Our op-ed rests on the benefits and costs summarized in the chart.

Why, then, do many people seem anxious about, if not downright opposed to, congestion pricing? Entitlement plays a part: Why should we suddenly be forced to pay for something that had been free? Another reason surely is disbelief. Many people don’t believe that the revenues — the $1 billion a year from drivers — will actually improve mass transit services. The M.T.A. is a money pit, people say.