Perhaps you saw our recent point-counterpoint dissection of Matto Mildenberger and Leah Stokes’ Boston Review article, The Trouble With Carbon Pricing. Both authors, political scientists at the University of California’s Santa Barbara campus, published books on climate policy this year — Carbon Captured: How Business and Labor Control Climate Politics (Mildenberger), and Short Circuiting Policy: Interest Groups and the Battle Over Clean Energy and Climate Policy in the American States (Stokes). Stokes has gained a devoted following in the climate movement for the flair with which she articulates a “standards-investment-justice” policy frame that relegates carbon taxing and other so-called “market mechanisms” to at most a subsidiary role.

Niskanen Center’s Joseph Majkut. “With carbon pricing, the private sector will be chasing opportunity instead of compliance.”

In our post we rebuffed that “market mechanism” label. “Taxing carbon emissions has nothing to do with ‘markets’ and everything to do with fixing the enormous market failure that allows fossil fuel companies and monster-truck drivers and frequent flyers pay zero for climate pollution,” we wrote. We also called on the climate movement to “harness the growing fury at the ever-expanding wealth gap with a program to tax both extreme wealth *and* carbon emissions and invest the proceeds into the Green New Deal” — a program we outlined last year.

Now comes the Niskanen Center’s climate policy director Joseph Majkut with his own response to Mildenberger and Stokes (M&S). Befitting the center’s standing as a politically grounded policy shop, The Immediate Case for a Carbon Price is savvy and compelling.

Whereas M&S largely dismiss carbon pricing as too chancy and slow to deliver large-scale low-carbon infrastructure, Majkut contends that pricing will bear fruit more quickly than regulations mandating and investment:

A carbon tax will start working almost immediately and be on solid legal ground, while complex regulations will take years for government agencies to craft and defend in court. If immediacy is necessary, then a carbon price is our best tool. (emphasis added)

Majkut also argues that the policies M&S tout, such as low-carbon procurement or production standards, targeted tax credits and expanded R&D, “will be more effective in a world where carbon pricing is a certainty.”

“Regulatory predictability and market certainty come from a carbon price,” he writes, “not from continually changing command-and-control measures.” With carbon pricing, he insists, “The private sector will be chasing opportunity instead of compliance.”

That last point resonates strongly with us. In an earlier (2012) point-counterpoint with Vox’s David Roberts (then at Grist), we wrote that “Standards and regulations tend to motivate threshold-meeting behavior but no more,” whereas the impacts of carbon pricing are unconstrained by this or that limit. In effect, raising the price to burn carbon imbues every fossil fuel-using process, decision or investment with a newly profitable opportunity to use less. Skeptics of the power of carbon pricing tend to overlook this dynamic, in keeping with their focus on Big Oil and their relative indifference to individuals’ role in fuel use and carbon burning.

That last point resonates strongly with us. In an earlier (2012) point-counterpoint with Vox’s David Roberts (then at Grist), we wrote that “Standards and regulations tend to motivate threshold-meeting behavior but no more,” whereas the impacts of carbon pricing are unconstrained by this or that limit. In effect, raising the price to burn carbon imbues every fossil fuel-using process, decision or investment with a newly profitable opportunity to use less. Skeptics of the power of carbon pricing tend to overlook this dynamic, in keeping with their focus on Big Oil and their relative indifference to individuals’ role in fuel use and carbon burning.

Here are more bon mots (actually, well-chosen sentences) from Majkut’s post, following by a few dissents.

- U.S. goods are 80 percent more carbon-efficient than the world average. If that difference were recognized in prices, U.S. manufacturers would have an immediate competitive advantage and the incentive to build upon it.

- Price signals are a major pull for innovation. Carbon pricing is a path to technology-neutral clean energy innovation and will spur investment in new technologies.

- Congress has the constitutionally articulated power to lay and collect taxes. Even the most conservative judiciary will be hard-pressed to find a constitutional objection to levying an excise tax on carbon dioxide emissions.

- Even before affecting home heating bills or prices at the pump, future tax obligations from the carbon price would drive investment decisions for every power plant, factory, and pipeline in favor of low-carbon alternatives.

- Carbon pricing is fairly popular when framed as a tax on fossil fuel polluters for the damages caused by their products. The Yale Climate Opinion maps show that 68 percent of Americans favor making fossil fuel companies pay for carbon in their products.

- M&S are right that economists’ dreams of solving the climate problem with carbon pricing alone have not materialized anywhere. However, even if policymakers are not willing to rely on pricing alone, it is clear that almost any conceivable set of standards and regulations would operate more rapidly and efficiently if combined with a carbon price.

- M&S write that “[c]arbon pricing has dominated conversations around climate policy for decades, but it is ineffective. Only a bold approach that centers politics can meet the problem at its scale.” I argue that as soon as we are having an actual conversation about imposing a climate policy that meets the problem at its scale, a carbon tax will live.

Where CTC differs from Niskanen

- Much of the business community, including a sizable portion of the fossil fuel industry, now favors climate action via carbon pricing. The remaining encampments of climate denial are shrinking both in industry and government… The denial apparatus that formerly united the fossil fuel industry with their political allies is losing members as the coal industry shrinks, and the oil industry supports carbon pricing. Yes, that climate denial is shrinking, No, that the fossil fuel industry has come to favor carbon pricing. A few oil companies may have signed on to the Climate Leadership Council’s blueprint with a $40 per tonne of CO2 carbon price, but neither the blueprint nor the signatories have committed to the kind of robust price-per-ton increases needed to do the heavy lifting of deep decarbonization. Moreover, initialing a policy paper is a far cry from putting political muscle behind legislation. Count us as deeply skeptical that any fossil fuel company will ever embrace meaningful carbon pricing.

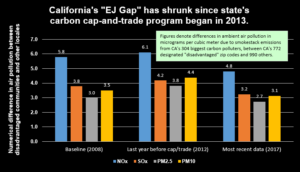

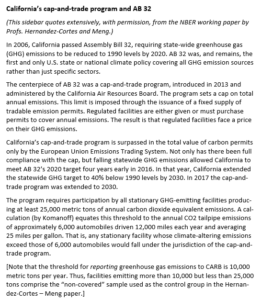

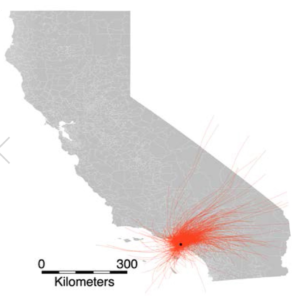

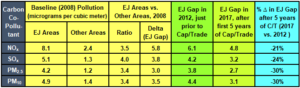

- [The standards] approach will have to resemble California’s, with a complex mix of policy instruments to reduce emissions from transportation, homes and buildings, and industry. While that state is making substantial progress toward its renewable energy goals, it stands to miss its climate targets. Those targets are far more ambitious than any other state’s. Indeed, as we reported last year, for decades California has far outpaced the other 49 states in shrinking its use of fossil fuels relative to economic output, so much so that U.S. emissions would now be nearly 25 percent lower if the entire country had kept pace. Majkut also missed an excellent chance to cite the NBER working paper that found that California’s cap-and-trade program has significantly shrunk the state’s “environmental justice gap.”

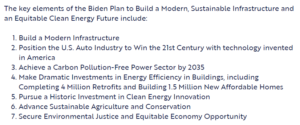

- A plan based on standards, investments, and justice may help build a left-wing coalition, or even pass in California or a few East Coast states. But at the national level, it will require significant new regulations, funding, and administrative capacity. Majkut’s link is to David Roberts’ affirmative post for Vox earlier this year, “At last, a climate policy platform that can unite the left,” that laid out the standards-investment-justice (S-I-J) triad that undergirds M&S’s article. In our opinion, he does both Roberts and M&S a disservice by labeling it left-wing. Indeed, the entire thrust of Roberts’ post, voiced in its subhead, is that “The factions of the Democratic coalition have come into alignment on climate change.” Not just the leftier parts, but every component of the Democratic Party, including centrists, labor and people of color.

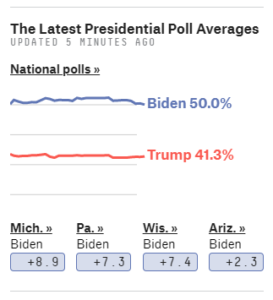

It’s not surprising or even disconcerting that the center-right Niskanen Center would find fault with a center-left standards-investment-justice climate policy frame that disses carbon pricing. At CTC we’re still striving for a policy synthesis that combines S-I-J with carbon pricing, along the lines we sketched in our midsummer post, If the Democrats run the table in November. Unlike Mildenberger and Stokes and, evidently, Majkut and Niskanen, we don’t wish to choose between the two.

That said, Majkut’s post is a worthy and welcome counterweight to the naysaying about carbon taxing that has come to be de rigeur for the climate left. We invite everyone engaged in climate advocacy and interested in carbon pricing to give it a good read.