Komanoff: The Time Has Never Been More Right for a Carbon Tax (U.S. News)

Search Results for: komanoff

Komanoff asks: If efficiency hasn’t cut energy use, then what?

Komanoff asks: If efficiency hasn’t cut energy use, then what? (Grist)

Komanoff: Senate Bill Death = Win for Climate

Komanoff: Senate Bill Death = Win for Climate (The Nation)

Q&A: Charles Komanoff

Q&A: Charles Komanoff (Mother Jones)

Defending NY’s Congestion Pricing Program

This post first appeared in The Washington Spectator, which posted it yesterday, Feb. 19. We’ve edited it slightly: swapping in a more finely-grained pie chart of trips to the zone by mode, adding a Hochul-vs-Trump graphic, and substituting excerpts from and a link to Gov. Hochul’s Grand Central Station press conference in place of an earlier quote from Reinvent Albany head John Kaehny. The remaining content is the same.

— C.K., Feb. 20, 2024

So much winning. Unjammed bridges and tunnels. Speedier deliveries. On-time buses. Calmer, more inviting streets. Fewer traffic crashes. Repairmen getting to more jobs.

Not Donald Trump’s kind of winning, however. Trump didn’t invent congestion pricing. A Nobel economist — a Canadian, at that — worked out the theory 60 years ago, and a ragtag crew of transit lovers, car inquisitors and dyed-in-the-wool urbanists spent decades importuning New York’s political establishment to put it into practice.

The president had nothing to do with the toll plan. In fact, everything about it screams woke — or does to troglodytes too blinkered to see that congestion pricing’s biggest beneficiaries are motorists, who daily reap substantial dividends in saved travel time.

So it came as no surprise that today Trump’s transportation secretary Sean Duffy told NY Gov. Kathy Hochul that the president intends to rescind federal approvals and to terminate the toll program, which went into effect in early January.

Fortunately, officials at the state-chartered Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which operates the city’s buses, subways and major bridges, and was invested half-a-dozen years ago with legal authority to administer the congestion pricing program, were ready. Mere minutes after Duffy’s announcement, the MTA filed a 51-page complaint in federal court charging Duffy, U.S. DOT and the Federal Highway Administration with usurping their statutory authority and seeking to bar them from interfering with the tolls.

Ozempic for Cities

“Am I tripping?,” shock jock Kai Cenat asked on Hot-97 last month. “Congestion pricing might actually be working.” Self-styled housing advocate YIMBYLAND pointed to plummeting subway crime and dubbed congestion pricing “the Ozempic of urbanism,” musing, “I wonder what else it can fix.”

Congestion pricing’s success at cutting traffic is winning converts.

The answer is: quite a lot. The unmistakable takeaway thus far is that just a few fewer cars goes a long way. The drop in the number of vehicles driven into the toll zone is probably 10 percent tops (conclusive data isn’t out yet). But it feels like more. In the papers and on TV, drivers are reporting less time stuck in their cars. In a recent poll, habitual car commuters to Manhattan strongly backed congestion pricing.

The “stick” that has dialed down traffic’s manifold negatives is actually fairly modest — a $9 toll to drive into Manhattan south of 60th Street. Compare that to my calculation that a median car commute to and from the congestion zone slows down the other cars, trucks and buses in its gravitational field by an aggregate of minutes and seconds that equate to $100 worth of lost time. As the toll “carrot” kicks in, in the form of $15 billion worth of transit improvements that the toll revenues will bond, subway travel will get better and safer, helping shrink car use even more.

To be sure, traffic will rebound somewhat as drivers feel the allure of less-clogged roads. But unlike traffic cops or synchronous traffic lights or other traffic-taming nostrums perennially attempted in New York and other U.S. cities, congestion pricing will yield a durable drop in traffic. Sure, call it a miracle. I have. But the eased traffic is the predictable product of pricing “congestion causation” into car trips that collectively create traffic jams.

The Serpentine Road to Jan. 5

What looks straightforward in print was, in practice, anything but. In Diary of a Transit Miracle, published in The Washington Spectator last April, I traced the 50-year effort to define, scope, build support for, and legislate New York congestion pricing. The miracle, I wrote, was three-fold: “Winners will far outnumber losers; New York will be made healthier, calmer and more prosperous; and that this salutary measure is happening at all, after a half-century of setbacks.”

Soon enough, the triumphant odyssey was torpedoed in the bow. On June 5, Gov. Kathy Hochul, whose office has authority over the MTA and, thus, over congestion pricing, peremptorily and indefinitely “paused” its June 30 start — a perfidy I dissected in Hochul Murder Mystery. The outbreak of pro-congestion pricing support would persist, I predicted, returning the governor to the fold — as happened in November, after the election. Congestion pricing would go into effect on Jan. 5, though scaled back from the June 30 rates. The intended $15 peak toll was lowered to $9, with truck tolls and taxi and Uber surcharges reduced by 40 percent as well.

Congestion pricing supporters at Lexington Ave. and 60th Street, 12:03 a.m. Jan. 5, 2025. I’m at center, foreground, holding yellow sign and chatting with journalist-author Christopher Ketcham. Tall man smiling at right is Rit Aggarwala, who led Mayor Bloomberg’s 2007-2008 bid to enact congestion pricing and now heads the city’s Dept of Environmental Protection. Photo: Sproule Love.

Even diminished, congestion pricing promised much for New York — especially if Hochul or a successor adhered to her pledge to raise the toll to $12 in 2028 and, in 2031, to the full $15. Toll supporters gladly took the win. As midnight approached on Jan. 4, we thronged Lexington Avenue and 60th Street, braving the midnight cold to count down the final seconds of life without congestion pricing.

We were festive and appreciative. “NY ♥s drivers who pay,” read my sign. “Thank you for paying the toll,” said another. “You’re making history!,” proclaimed a third. No one asked if “you” denoted the crowd, or the drivers whizzing by, or our fair city. For a bright, shining hour, it was everyone.

Why Trump Wants to Eradicate Congestion Pricing

Once upon a time, a wannabe developer looking to make a mark in Manhattan might have bet on congestion pricing. Wharton might have schooled him that prices beat queues at sorting supply and demand. He might have paid notice in the 1980s as true-life real estate titan Dick Ravitch used his pulpit as MTA honcho to hammer home that a thriving Gotham required functional transit, which in turn required robust new revenue streams. Throughout Mike Bloomberg’s mayoralty, he might have listened as Kathy Wylde, chief of the blue-ribbon business group Partnership for New York City, repeatedly decried region-wide traffic gridlock as a $20 billion a year tax on residents and businesses.

Meanwhile, of course, Donald Trump did none of those things. From time to time he fulminated against congestion pricing, though more as a nuisance like, say, water-saving flush toilets. As president he escalated his rhetoric. In a Feb. 8 interview with the New York Post, Trump called the tolls “horrible” and “destructive to New York.” Ignoring mounting evidence like January’s big year-on-year uptick in attendance at Broadway shows, he dismissed the reductions in traffic jams, rationalizing that “Traffic is way down because people can’t come into Manhattan and it’s only going to get worse.”

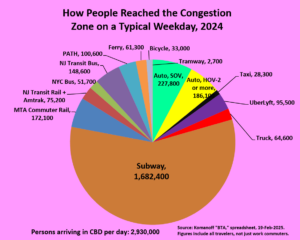

That’s your standard “windshield perspective” at work, oblivious to the reality that barely one-fifth of folks coming to the Manhattan congestion zone arrived in a private vehicle prior to congestion pricing. (See chart.) True enough, a few days after Trump’s Post interview, local news sources reported a rise in Manhattan foot traffic in congestion pricing’s first month compared to the year before.

Pre-tolling, only one-fifth of person-trips to the congestion zone were via private vehicle; among regular work-commuters the share was even smaller.

Still, the Trumpian brain gazing at congestion pricing sees not a respite from traffic gridlock but oil barons’ birthright squandered on mass transit and climate. Ironically, the tolls’ direct hit to petroleum and carbon will be relatively modest; by design, congestion pricing applies just to a sliver of city driving.

If congestion pricing had a motto, it would be, “Don’t ban cars, bill them” —a mantra lost on The New York Times, which today wrote> that the tolls “aimed to discourage drivers from entering the congestion zone.” Wrong. Congestion pricing seeks to dissuade a smallish fraction of drivers — 10 to 20 percent — from doing so. The other 80 to 90 percent are meant to keep driving to ensure sufficient toll revenues to bond the promised transit investments.

Subtle truths be damned, congestion tolling is anathema to Trumpworld, where policy considerations are buried under monstrous simplification, crude disinformation, coarse slander and, most often, outright lies. Congestion pricing’s crime is that it elevates the collective interest above individual actions that threaten it. It requires drivers to Manhattan’s teeming center to either change their behavior for the common good of congestion reduction, as Paul Krugman put it recently, or to offset some of the harms from their driving by paying into a government-administered kitty — to be invested in transit betterment that will reducing congestion further.

Krugman conjectured that “hostility to New York” may be the true font of Trump’s antipathy to congestion pricing. “Many people, and Trump in particular,” Krugman wrote, “are committed to the view that [New York] is an urban hellscape. A policy that improves life in the city runs counter to that narrative and inspires visceral opposition. And Trump in particular surely wants to hurt a city that has never supported him.”

A balm for New York, if we can keep it

It’s easy to be gloomy about congestion pricing’s ability to overcome Trump’s enmity. Even if the MTA prevails over Secretary Duffy in federal court — and the Authority appears to have a strong hand — the Trump administration has myriad ways to coerce New York State into ending the program. It could slow Federal Transit Administration reimbursements to the MTA for expenditures already authorized and made. Going forward, Trump could constrict routine federal contracts to rehabilitate and build new transit. The rational choice for the state and MTA might then be to give up the toll program.

Or, Trump could hold that power in reserve as leverage to get New York City and State to fall in line or not make waves on a hundred other fronts. Not selling out congestion pricing requires Gov. Hochul to be steadfast and for Mayor Eric Adams, who began distancing himself from the tolls long before bending his knee to Trump, to leave or lose his mayoralty to a congestion pricing defender.

Hochul, for her part, is off to a rousing start. Addressing congestion pricing supporters at NY’s Grand Central Station yesterday, she said:

At 1:58 pm, President Trump tweeted, ‘Long live the king.’ I am here to say that New York hasn’t labored under a king in 250 years and we are sure as hell not going to start now… We stood up to a king and we won then. In case you do not know New Yorkers, we’re in a fight, we do not back down — not now not ever… I don’t care if you love congestion pricing or hate it, this is an attack on our sovereignty, our independence, from Washington. We are a nation of states. We are not subservient to a king or anyone else from Washington… We will not [let] the commuters of our city and our region [become] roadkill on Donald Trump’s revenge tour against New York.

But to feel the governor’s steely determination to keep congestion pricing, it’s best to hear her. This 20-minute YouTube video of her and MTA chief Janno Lieber leaves no doubt that she is more than ready to go to the mat with Trump. She sounds positively liberated.

“King” Trump vs. Gov. Hochul. Diptych courtesy of Ryder Kessler, Abundance New York.

Of one thing we can be sure: For Hochul to maintain her brave stance will require continued, sustained organizing — more of the grinding work that brought congestion pricing to life in the first place. The old saw about genius being 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration applies here.

In this trilogy’s first installment, I gave pride of place to congestion pricing theorist Bill Vickrey. So did the Times’ “Big City” columnist, in an encomium to the Nobel economist last month that implicitly treated the unceasing toil of congestion pricing’s legions of supporters over the years like so many dust bunnies.

But the Jan. 5 victory belongs not just to Vickrey and Ravitch and Wylde, or to Lieber and his relentless staff, but also to Riders Alliance, Reinvent Albany, Regional Plan Association, the Community Service Society, a revitalized Transportation Alternatives, and scores of allied organizations and associations that together coalesced into a civic force for municipal progress, good governance and improvements in our quality of life. And to the journalists who gave our labors prominence.

These organizations internalized and acted on the twin beliefs that having too many cars hurts cities, and that traffic pricing is indispensable for diminishing the automobile’s stranglehold over transportation budgets and road designs. After Hochul’s congestion pricing “pause” last June, they rose as one to block her ploy to concoct a substitute transit funding source. “We never considered it, not for a minute,” Riders Alliance senior organizer Danna Dennis told me earlier this month. “It was congestion pricing all the way.” Likewise for Liz Krueger, state senator from Manhattan’s east side, who rallied her Albany colleagues to render the governor’s gambit dead on arrival.

The result, on Jan. 5, was an epic breakthrough. For the first time in the USA, driving is being assessed a charge for some of the immense harms it wreaks on urban life. At this writing, 45 days on, the facts on the ground are everything that congestion pricing proponents dreamed of and promised. Every new day that dawns with the tolls intact puts the lie to the claims of Trump’s minions that the program is hurting New York. Sure, like Ozempic hurts the chronically obese.

It can feel unfair to have to keep on defending a program that has the force of law and is working wonders. But we must and we will.

A Lesson for NYC Congestion Pricing Came Last Week from Washington State

This post is adaped from my essay yesterday on Streetsblog USA, A Lesson for NYC’s Congestion Pricing Came Last Week from Washington State. It was posted on the eve of NY Gov. Kathy Hochul’s announcement today that she has ended her June “pause” and authorized New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority to begin implementing a scaled-down but still-robust version of the original plan, beginning at midnight January 5, 2025.

The Streetsblog post was intended to steel Hochul’s courage and, as we congestion pricing advocates have demanded since June, to prod her to “flip the switch” on the Manhattan toll scheme that was set to go into effect on June 30. It was actually written last weekend with the hope of placing it in the New York Times, but they could not fulfill our request for rapid publication. No matter, the governor’s turnaround was already in the works.

The post takes a few liberties with actual events in Washington, eliding the differences between the straight-up carbon tax measure that voters rejected in 2016 and the cap-and-trade measure that also failed at the ballot in 2018, and the state’s Climate Commitment Act that was enacted into law in 2021 and backed by voters last week. This was in service of the larger point: that the conception of what is fair changes when an effective policy has been given time to work, and that if a policy is wise, politicians should stay the course, confident that public support will emerge.

We’ll have more to say in the coming weeks about the pending rollout of New York’s congestion pricing plan, arguably the first-ever large-scale application of externality pricing in the U.S.

— C.K., Nov. 14.

The first time Donald Trump was elected president, in 2016, Washington State residents also voted down an initiative that would have created the country’s first statewide carbon tax.

The second time Trump won the presidency, last week, Washington residents flipped their 2016 stance on carbon pricing, voting to preserve the comprehensive carbon pricing program that their legislature ended up enacting. And therein lies a message for New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, who paused New York City’s Central Business District toll plan on June 5, just as it was about to go into effect after years of debate.

The message: If the policy is wise, stay the course. The facts on the ground will soon change, generating the political support to validate your policy and prepare you for the next policy battle.

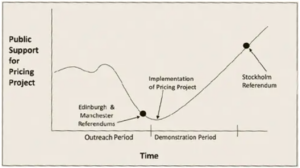

The famous chart of why politicians should stay the course when a policy is good, but unpopular.

Congestion pricing proponents have always known the odds. Taxes are unpopular, check. Driving is a birthright and change is hard, check. We were aware congestion pricing in London and Stockholm had only 40 percent favorability before adoption. But both cities’ experience showed that once traffic visibly lessened and transit improvements got underway, opinion flipped. Roughly 60 percent of residents now support the tolls.

The 2016 vote against Washington carbon pricing was a landslide: 59.3 percent no to 40.7 percent yes. The 2024 vote to keep the state’s carbon pricing law was a landslide in the opposite direction: 62 percent to keep it and 38 to repeal it. Hmm, looks like that 60-40 rule has legs!

A brief look at the law that Washington State voted to keep last week will demonstrate how it’s cut from the same cloth as New York’s congestion pricing.

Washington’s innovative Climate Commitment Act requires fossil fuel companies to buy permits keyed to the carbon content of their fuels. That includes oil refineries, which pass on the costs of the permits to motorists and homeowners as higher prices for gasoline and heating fuels.

The intent is to motivate industry and consumers to curb their carbon dependence, much like congestion pricing in New York would impel motorists to drive less often into gridlocked Manhattan. Sales of the emission permits in Washington are already helping finance electrification and renewable-energy substitutes for fossil fuels, just as New York’s congestion revenues would have bankrolled $15 billion in better transit.

And just as it has been in New York, the road to this decision wasn’t easy. Washington’s climate law took root after voters twice rejected ballot referendums for statewide pricing of carbon emissions by margins of around 60 to 40. (A 2018 initiative failed as well, 56.6 percent to 43.3percent.) But after Democrats won control of the legislature in 2020, Gov. Jay Inslee, a Democrat and unabashed climate champion, pushed through the Climate Commitment Act, much as New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo in 2019 won legislation directing the regional transit authority to institute a congestion pricing system.

This year, however, fossil fuel backers in Washington collected enough signatures to place Initiative 2117on the Nov. 5 ballot. A “yes” vote would have repealed the legislation and discarded the emission permits — perhaps slowing energy price increases but stalling the state’s shift toward clean power.

Well, the returns are in, and supporters of the emissions permit scheme won big.

True, what was on the ballot in Washington last week — making gasoline and other fossil fuels more costly to elevate lower-emission substitutes from smaller cars to electric cars and, best of all, less driving — isn’t the same as congestion pricing. But it’s a close cousin. What stands out is that a policy rejected by nearly 60 percent of voters in 2016 and again in 2018, won with around 60 percent in 2024. Attitudes can shift when facts warrant.

True, what was on the ballot in Washington last week — making gasoline and other fossil fuels more costly to elevate lower-emission substitutes from smaller cars to electric cars and, best of all, less driving — isn’t the same as congestion pricing. But it’s a close cousin. What stands out is that a policy rejected by nearly 60 percent of voters in 2016 and again in 2018, won with around 60 percent in 2024. Attitudes can shift when facts warrant.

What enabled the turnaround? A resolute governor stayed the course, allowing the “default” to recalibrate from cheap gas to clean power and letting the public warm to this novel policy for cutting carbon pollution. Once it did, 20 percent of voters came aboard, just like they did in London and Stockholm.

New York hasn’t been as fortunate yet. This spring, our executive gazed at the pending $15 peak congestion toll and rather than seeing less gridlock and a transformed transit system, saw a political abyss. Advocates and even her own staff tried to brace her for this “valley of political death” between congestion pricing’s initiation and its eventual acceptance. The warnings did no good. On June 5, she placed the tolls on “indefinite pause.”

There is talk that the governor will soon un-pause the tolls now that the suburban House races she feared would be swept up in a congestion pricing backlash are decided. But Gov. Hochul must move with urgency. The incoming president has made his distaste for the tolls abundantly clear. His return to power is less than 10 weeks away, with at least four of those weeks likely gobbled up by red tape. The plan’s logic that Hochul herself once articulated so well remains intact: better commutes and healthier, safer streets.

Hochul must act fast and trust the message from Washington State: with strong leadership, good policy and good politics can be one and the same.

Another venue ripe for cost internalization: NYC food delivery

This post was published earlier today by the New York livable-streets site Streetsblog, under the headline Reining in Deliverista Distances is the Key to Safety. I’ve cross-posted it here because the proposal it conveys — a per-mile charge on app-based food deliveries — is an easily understandable illustration of the principle of “cost internalization” embodied by carbon taxing. Other recent illustrations are Strawberry Yields Forever, which reported on a grower-backed tax on groundwater in California’s Pajaro Valley; A Tantalizing New Front in Externality Pricing, about a proposed tax on helicopter noise; and periodic posts on the twists and turns in the long campaign to implement congestion pricing in New York City (here and here).

The text here duplicates the expositon in Streetsblog but near the end adds a paragraph contesting the widespread presumption that externality pricing necessarily injures marginalized groups (environmental justice communities, in the case of carbon pricing; food-delivery riders, in the case of the mileage charge outlined here).

— C.K., Nov 5, 2024.

Food deliveries in New York are spanning ever-longer distances. Before food apps, and before motorized bikes, deliveries came from nearby — from the local pizza parlor or neighborhood joint. Now deliveristas can be seen traversing the East River bridges or blasting up the Hudson River Greenway and the Central Park drives. When I ask a delivery rider at a red light how far he’s going, it’s often much more than a mile.

I’ll say it out loud: All that DMT — Deliverista Miles Traveled — has become a drag on other city cycling. It’s made the streets more chaotic and is stressing our bicycle lanes. Routine cycling maneuvers like sliding over in the bike lane or turning now require constant signaling and checking to avoid getting clocked from behind.

Photo: Josh Katz. Photo montage: Streetsblog.

Cars and trucks remain the greater danger, of course. But I find lumbering vehicles easier to anticipate and navigate around than darting mopeds or e-bikes. No, I’m not giving up cycling, but I’ve lost count of how many acquaintances have. The need for vigilance and the fear of being taken down in a crash became too great.

What the Comptroller Missed

City Comptroller Brad Lander last week issued a report, Strategic Plan for Street Safety in the Era of Micromobility, aimed at safeguarding workers and minimizing dangers to the public from the food-delivery industry.

As Streetsblog reported, Lander wants the city to exert authority over app companies like DoorDash and Uber Eats that process 90 percent or more of food deliveries in the five boroughs.

His suite of reforms is a start, especially jawboning officials to throttle the import and use of non-UL e-bike batteries like the ones that have sparked scores of serious fires.

But it misfires in pinning its street-safety aspirations on an empowered workforce and a semblance of enforcement by NYPD. The first can only go so far. The second appears to be a pipe dream. Lander also failed to include the lowest-hanging fruit for food-delivery safety: reining in deliverista miles traveled.

Reduce ‘Deliverista Miles Traveled’

Picture 40 percent of citywide food-delivery e-bike and moped miles eliminated. This would greatly enhance everyone’s safety, not just by directly cutting the sheer amount of fast and sometimes startling two-wheeling but also by dialing down street chaos and helping other cycling regain a footing in bike lanes and general traffic.

So how would that be accomplished? Mathematically, by shaving a mile from current deliveries covering a mile or more

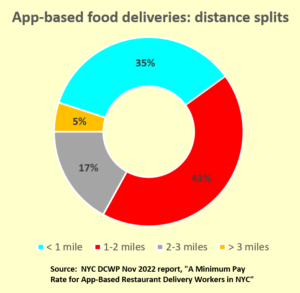

According to a 2022 report from the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection, nearly two-thirds of the city’s app-based food-deliveries exceed one mile. (And nearly one-quarter of all deliveries extend for two miles or more.) Trimming a mile from those deliveries would reduce average delivery distances to 0.85 miles from the current 1.50 — a 43-percent reduction that I round down to 40 percent.

Nearly two-thirds of app-based food deliveries in New York City cover more than one mile, according to city data.

How can we make this shrinkage come about? By taxing app-based food deliveries for each mile beyond an initial free mile — as I outlined over a year-and-a-half ago in the Streetsblog piece, “Want Safe Batteries? Stop Pretending Food Delivery is Free.” The dollar-per-extra-mile fee would be doubled in Manhattan south of 60th Street, where food choices are abundant and foot traffic and road congestion are heaviest. The charges would be paid to the city by the app companies, who would tack it on the bill — creating an incentive for customers to order from eateries closer to home.

I can’t say conclusively that my dollar charge will bring about the envisioned 40-percent mileage reduction. I can confidently predict traffic reduction from congestion pricing because there is so much data about car trips, but food-delivery mileage charging is uncharted territory. The dollar charge for deliveries over a mile might have to be higher, or perhaps could be lower, but we’ll only know if the city conducts surveys or a simulation with randomly selected families spending down pre-filled accounts.

What I can say with confidence is that the delivery mileage charge would generate a ton of revenue — perhaps not my earlier estimated $100 million a year, but close to it. This pot could pay to swap out unsafe batteries and establish deliverista hubs. Some of these endeavors are already under way, happily, and the Comptroller’s plan would move things along, though on the taxpayer’s dime.

(Don’t) Walk on the Demand Side

The omission of a delivery-mileage charge from Lander’s report is a huge missed opportunity, but it wasn’t surprising. New York City’s leading cycling advocacy group, Transportation Alternatives, has yet to mention the idea in its policy papers. Perhaps in striving for solidarity with deliveristas, TA has short-shrifted the concerns of non-commercial cyclists — as Michele Herman, lead author of TA’s classic Bicycle Blueprint (PDF), argued this year in the Village Sun.

Lander’s omission also mirrors the tendency in environmentalist circles to turn a blind eye to the consumption aspect of so many policy questions. Climate protesters picket at banks that they say enable drilling and pipelines, but not at the gas stations at which motorists dutifully fill Big Oil’s coffers or at showrooms pimping the machines that actually combust the petrol. Similarly, the decade-long project to divest pension funds and universities from fossil fuels didn’t cut carbon extraction and burning one iota. It did, however, divert “YIMBY” activism that is vital to New York and other inherently low-carbon cities.

Climate may seem gargantuan vis-a-vis food delivery, but the parallels are powerful. Both spheres treat “demand” as inviolate. Just as suburban households are allowed McMansions and fleets of SUVs, we city dwellers are unquestioned on our right to order meals and treats anytime from anywhere.

Externality pricing is sidelined in both spheres as well. Just as carbon taxes would crush demand for coal, oil and gas, a dinner-delivery mileage charge would help rebalance ordering from faraway to nearby, adding a measure of predictability and orderliness — hence, safety — to city streets, far more than policing could ever do. Yet internalizing even a sliver of an activity’s harms into its price is out of bounds in contemporary discourse. Congestion pricing, whose supposedly “too high” $15 toll would have only offset one-sixth of a car trip’s congestion causation cost, got shelved lest drivers flip out.

And let’s not overlook the diktat granting veto power to potentially afflicted outgroups. In carbon pricing, those are primarily environmental justice communities deemed threatened by carbon emissions charging, even though economic mitigations are readily available and EJ communities suffer the greatest damage from extreme heat, flooding and other climate-wrought disasters.

Delivery-mileage pricing would directly affect the city’s 65,000 deliveristas, of course, but perhaps not adversely. Diminishing deliverista miles traveled wouldn’t equally diminish their employment and wages, since total deliveries would be largely unchanged. What would almost certainly fall is the terrible annual toll of a dozen or more fatal on-the-job crashes.

No sector of labor (or business) in New York City should be held sacrosanct. All should be governed for the greater good. Food delivery regulation should advance social safety without infringing on worker power. A mileage fee on food deliveries can serve workers as well as the society of which they’re a part. What are we waiting for?

What Are EVs Good For?

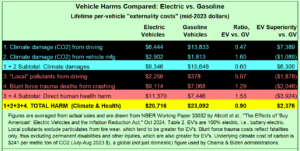

This essay also appeared today in Streetsblog USA. The version here adds a table and line graph and a few explanatory words.

U.S. electric vehicles are only slightly less harmful to the environment and society than conventional gasoline cars, according to a new in-depth analysis by researchers at Duke, Stanford, U-C Berkeley and the University of Chicago.

This surprising finding — a mere 10 percent difference between electric and gasoline vehicles’ lifetime externality costs — emerges from a detailed “working paper” that the team of researchers posted earlier this month to the prestigious National Bureau of Economic Research.

The paper, The Effects of ‘Buy American’: Electric Vehicles and the Inflation Reduction Act, includes the first attempt in a decade or more to monetize and aggregate automobiles’ primary direct harms: climate damage from manufacture as well as driving, along with crash deaths and non-climate pollution. EVs perform worse than GVs (gasoline vehicles) on three of these scores, according to the paper. Only on climate-damaging carbon emissions from driving do electrics triumph decisively over gasoline cars.

The paper, The Effects of ‘Buy American’: Electric Vehicles and the Inflation Reduction Act, includes the first attempt in a decade or more to monetize and aggregate automobiles’ primary direct harms: climate damage from manufacture as well as driving, along with crash deaths and non-climate pollution. EVs perform worse than GVs (gasoline vehicles) on three of these scores, according to the paper. Only on climate-damaging carbon emissions from driving do electrics triumph decisively over gasoline cars.

What’s keeping EVs from slam-dunk superiority over GVs? In a word, batteries. The batteries required to keep an electric vehicle moving make car manufacture far more energy-intensive for EVs than GVs, while their increment to vehicle weight — half-a-ton for a small EV, a ton or more for a standard large — renders EVs deadlier in crashes.

None of this comes as news to regular Streetsblog readers or aficionados of “car bloat” arch-foe journalist David Zipper. The new wrinkle in the NBER paper is its extensive monetization of harms. The paper suggests that the combination of EVs’ excess manufacturing energy and extra weight-caused fatalities undoes a third to a half of electric vehicles’ societal benefit from their lesser carbon emissions from driving. (See graph above.)

There’s more. Putting aside CO2 and climate, the NBER paper rates electric cars as worse polluters than gasoline cars when electrics’ associated smokestack emissions are properly counted. Yes, you read that right: the paper finds that particulate and gaseous emissions resulting from EV battery recharging are more harmful to health and the environment than gasoline cars’ tailpipe emissions — contrary to widespread faith in electric cars as an urban pollution solution.

Incremental vs. Average Emissions

Making sense of that finding starts with grasping that emission controls and cleaner gasoline — mandated by federal regulations that the auto and oil industry fought every step of the way — have slashed pollution from conventional autos compared to their 20th century precursors. I remarked on this enormous if underappreciated change in my tribute on Streetsblog to Brian Ketcham, the protean automotive engineer who died in August.

Data in table were used to derive bar chart, above.

Moreover, most U.S. power grids remain majority-carbon, notwithstanding wind and solar power’s rapid expansion. This means that plugging in an EV for recharging rarely summons additional power from non-carbon-based renewables or nuclear plants, since these are already running at their maximum capability. Rather, EV recharging anywhere in the 50 states tends to trigger increased output by gas- or coal-fired generators, especially the latter, which these days function as many grids’ swing generation.

The NBER authors’ pollution accounting meticulously (and correctly) assign those power plants’ incremental carbon and particulate emissions to the EVs. (Use of grid averages — the “default” in popular EV-climate discourse — isn’t just lazy, it greenwashes electric vehicles by crediting them with carbon-free electrons that should be allocated to pre-existing electricity usages.)

Despite my comfort with “incremental” rather than “average” pollution accounting — the approach I practiced in my long-ago career analyzing the U.S. power sector — I was still taken aback by the NBER researchers’ finding that EVs’ smokestack particulates and gases outweigh gasoline vehicles’ tailpipe harms by 6-to-1. But even dropping these “local damages” from the comparison, the other three harm categories combined give EVs only a 20 percent win vis-a-vis GVs. While that advantage ain’t beanbag, it’s a far cry from the prevailing conception of EVs as “green.”

It’s also a stark reminder of automobile dependence’s social unsustainability. Like it or not, the fact is that electric vehicles, though endlessly touted as benign, impose immense harms. And the NBER cost figures exclude the tens of thousands of permanently disabling car injuries each year (they only include fatalities), the health and ecosystem damage from the heavier EVs’ extra tire wear, and car culture’s budget-busting, soul-breaking impacts on Americans.

Also bear this in mind: The climate costs in the graph at the top of this post were calculated with a fairly aggressive “social cost of carbon” of close to $250. While the true cost of each metric ton of CO2 emitted today is probably higher — think of Hurricanes Helene and Milton, and the coming fallout from skyrocketing or unavailable home insurance, for starters — no country in the world actually prices (i.e., taxes) its carbon emissions at even half that rate. Using cost figures in the NBER paper, I’ve calculated that at any social cost of carbon below $150, the average EV is more harmful societally than the average gas vehicle.

That EVs improve only modestly on GVs under reasonably broad social accounting is sobering. Yes, their climate benefit is substantial, around 1.7 to 1 (throwing in manufacturing CO2 with driving CO2). But that ratio is miles away from a clean sweep. And with NIMBYs, NEPA and other obstacles to a truly green grid, it’s not going to rise very much for a while.

That EVs improve only modestly on GVs under reasonably broad social accounting is sobering. Yes, their climate benefit is substantial, around 1.7 to 1 (throwing in manufacturing CO2 with driving CO2). But that ratio is miles away from a clean sweep. And with NIMBYs, NEPA and other obstacles to a truly green grid, it’s not going to rise very much for a while.

A caveat: cataloguing and estimating automobile externalities, while a feature of the NBER paper, wasn’t its focus, which was to evaluate the generous subsidies to EVs (and their batteries) in the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. The paper itself is technical and laced with jargon and I may not have grasped every nuance.

That said, here are the NBER paper’s key bottom lines on car harms, as I understand them:

- Based on current U.S. electric grids, and including vehicle manufacture along with driving, EVs are 40 percent less climate-polluting on average than gasoline vehicles (GVs).

- Adding in the costs of car crash deaths to the above climate (carbon) pollution costs, EVs in the U.S. are 19 percent less societally harmful than GVs, on average.

- Also adding “local” tailpipe and smokestack pollutants to the calculation in #2, EVs are only 10 percent less societally harmful than GVs.

- Finding #3 rests on figures in the NBER paper indicating that smokestack pollution from EV charging causes six times as much health and other harms as GV tailpipe pollution — a finding that warrants close vetting. (The NBER authors directed me to their model results but refused my entreaties for a more convincing explanation of that finding.)

- Results 1-3 omit non-fatal crash injuries (an omission favoring EVs), particulates from tire wear (also favoring EVs), geopolitical entanglements from oil dependence (an omission favoring GVs), noise pollution, and other physical and societal maladies from automobile dependence.

- Even with those omissions, the lifetime unpriced costs from both types of vehicles average more than $20,000, a figure that would tack on 40 percent or more to today’s average U.S. $48,000 purchase price of new automobiles.

- Findings 2, 3 and 6 assume a fairly aggressive “social cost of carbon” — close to $250 per metric ton of CO2.

Yes, EV harms will diminish over time as U.S. grids decarbonize. Nevertheless, the NBER paper suggests that progress in that direction has fallen short of green hype, and that on a broad social scoreboard EVs’ greater mass is undercutting electrics’ climate potential.

What Price Giant Wind?

Belief that bigger is better — or, at least, a lot cheaper — helped sideline nuclear power. It now imperils wind power.

In July, at the first commercial-size U.S. wind farm under construction, near Martha’s Vineyard, a turbine blade split apart and fell into the Atlantic. In May and again in August, at the new Dogger Bank wind farm 80 miles east of England, blades broke off their towers and slammed into in the North Sea.

All three failures involved a mammoth new wind turbine design from GE Vernova, optimized to abundant offshore winds. The 13-megawatt turbines, dubbed Haliade-X by GE Vernova, a spinoff from the old General Electric conglomerate, are the world’s largest, and are nearly four times more powerful than the average wind turbine installed in the U.S. last year, and a full order of magnitude (10x) beyond typical windpower machines installed 20 years ago, according to U.S. Department of Energy data.

Photo of Vineyard Wind farm by Randi Baird. This image led the Sept 12, 2024 NY Times business section.

To be sure, dozens of other turbines at both wind farms are operating trouble-free and helping displace fossil-fuel generation, although the Vineyard Wind farm is now shut. The expected output of each 13-MW unit, 56 million kilowatt-hours a year, will let power grids pull back on incumbent fossil-fuel power plants that would otherwise spew 25,000 tons a year of climate-disrupting CO2, while maintaining wind energy’s meteoric growth. In Great Britain, wind turbines now stand neck-and-neck with power plants burning “natural” (methane) gas as the top electricity source, providing a third of Britain’s electric generation in the first quarter of 2024, according to Energy Advice Hub. In the U.S., although wind power’s kilowatt-hour production fell by 2 percent in 2023 — the first year-on-year slip this century — wind turbines are producing 40 times more electricity than two decades earlier and now account for 10 percent of the nation’s electricity generation.

Despite, or perhaps because of, wind power’s growing prominence, the concatenation of the three incidents is worrisome. The Vineyard breakage seemed to validate the fears of East Coast commercial fishers and other objectors to the large-scale offshore windpower development that has become a linchpin of regional and national drawdowns from fossil fuels. “Jagged pieces of fiberglass and other materials from the shattered blade drifted with the tide, forcing officials to close beaches on Nantucket,” the New York Times reported this week.

Indeed, the Times headlined its story on the Vineyard mishap, “Broken Blades, Angry Fishermen and Rising Costs Slow Offshore Wind,” adding the subhead, “Accidents involving blades made by GE Vernova have delayed projects off the coasts of Massachusetts and England and could imperil climate goals.”

What happened?

Why the blades broke apart isn’t yet clear. According to the Times’ story, GE Vernova has labeled the three incidents “one-offs rather than systemic flaws … but has provided few details about their causes.” The first failure at Dogger Bank, in May, resulted from “an error during installation,” a company spokesperson told the paper, while the second, in August, “happened because a turbine was left in a ‘fixed position’ during a storm.” Trade publication Maritime Executive reported that GE Vernova told investors that the Vineyard blade rupture resulted from a “manufacturing deviation” in the bonding of the blade at a Canadian production facility. But the company “declined to confirm any details about the blade[s] that failed at the UK wind farm and if [both] came from the same manufacturing facility,” the publication said.

[On Sept. 20, just hours after we posted this story, GE Vernova said it planned to downsize its offshore wind business with 900 job cuts, many at the company’s turbine factory in Saint Nazaire, France.]

A GE Vernova 13-MW wind turbine blade awaiting shipment offshore, photographed for NY Times by Bob O’Connor. Its weight is almost certainly double and perhaps triple that of conventional 3.3-MW blades.

The cause could be rooted in the sheer size of the blades and, perhaps, the rapidity with which the industry has scaled up. The blades on the Haliade-X offshore wind turbine are 50 percent longer than those on a representative 3.3-MW land-based wind turbine: 220 meters tip-to-tip for the 13-MW model, according to GE Vernova, vs. 148 meters for the 3.3-MW machine, per the U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s 2022 Cost of Wind Energy Review (pdf). The disparity in bulk is probably well over 2 to 1; if the blade shapes are the same, the ratio of their areas would be 1.50 squared, i.e., 2.25 to 1. If the bigger blades are thicker as well, their weight could be triple that of the conventional blades.

It may be that current technology can’t mass-produce such enormous objects to the quality required to withstand the stresses from constant rotation. Even slight manufacturing defects that smaller turbines could handle might be unforgiving for giantic blades.

This isn’t to say that advances in metallurgy, material bonding and non-destructive testing couldn’t restore reliability for giant wind turbines in the future. The checkered history of rapid size-scaling in the U.S. nuclear power industry may be instructive.

Boosting reactor sizes proved disastrous in the U.S.

Throughout U.S. nuclear power’s “bandwagon era” — circa 1957-1974 — the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and reactor manufacturers subscribed to the idea that nuclear costs would enjoy pronounced economies of scale. Their rule of thumb was that any doubling of reactor capacities — from 100 to 200 megawatts (for so-called “pilot” plants) and, later, from 500 to 1,000 MW — should raise costs only around 50 percent, tantamount to a 25 reduction in per-kW costs.

(The 50 percent cost rise would equate to a factor multiple of 1.50. Dividing that by two, for the doubling in megawatts, would yield a per-kW cost multiple of 0.75, i.e., a 25 percent drop.)

This impressive scale-economy made sense — on paper. Costs tend to track equipment surface areas, while capacity is proportional to reactor volume, portending only a 60 percent rise in costs per doubling of capacity. (Mathematically, two raised to the two-thirds power is roughly 1.6. Why two-thirds? Because surface area rises with the square of length while volume rises with the cube.) This would dictate a 20 percent reduction in per-kW costs from doubling plant capacity. Other cost elements like siting, permitting, engineering, and project mangement would, it was thought, display steeper economies, lifting the overall per-kW cost reduction per doubling of capacity to around 25 percent.

This impressive scale-economy made sense — on paper. Costs tend to track equipment surface areas, while capacity is proportional to reactor volume, portending only a 60 percent rise in costs per doubling of capacity. (Mathematically, two raised to the two-thirds power is roughly 1.6. Why two-thirds? Because surface area rises with the square of length while volume rises with the cube.) This would dictate a 20 percent reduction in per-kW costs from doubling plant capacity. Other cost elements like siting, permitting, engineering, and project mangement would, it was thought, display steeper economies, lifting the overall per-kW cost reduction per doubling of capacity to around 25 percent.

These upbeat expectations from reactor upsizing motivated successive doublings in reactor capacities through the 1960s and into the 1970s. The size increases did cut per-kW costs (or, at least, they helped hold back the tide of increased costs to comply with increasingly stringent safety regulations), but with diminishing returns. My own empirical analysis of costs to complete U.S. reactors, published in 1981, found only a 13 percent drop in per-kW costs per doubled reactor size, even when controlling for so-called regulatory creep. That saving was only half as great as the AEC had posited. Worse, larger reactors took far longer to build than smaller ones, which tied up vast amounts of capital, postponed nuclear displacement of fossil-fuel electricity, and spooked investors.

Larger reactors also proved harder to keep in service, their “teething” problems sometimes persisting for decades. That troublesome era is now decidedly in the past. The U.S. nuclear power sector’s average “capacity factor” has climbed steadily from the post-Three Mile Island accident trough of 55-60 percent operability to nearly 90 percent since around 2000. Still, with investor losses, high utility bills and excess carbon emissions, the toll from too quickly upsizing U.S. nuclear power plants proved immense.

A mid-range carbon price would match cost savings from doubling wind turbine sizes

The scale-economy curve for wind power in the graph above isn’t statistically stout, having been extrapolated from a mere two data points for land-based turbines in the NREL Wind Energy Cost report referenced earlier. (Readers with additional data: please share it with us!) That said, it conveys a message: double the size of an individual wind turbine and the per-kW capital cost should diminish by 18 percent. Factor in greater productivity — I assume that each kW of capacity of the larger turbine produces 9 percent more kWh’s than the smaller one — and the overall cost per kWh of wind power (“levelized cost of electricity,” in industry parlance) falls by 25 percent with a doubling of the turbine’s megawatt size.

That’s no small saving for supersizing, though of course it requires that projects employing the extra-large turbines actually come to fruition. According to the most recent (Aug. 19) Nantucket Town and County 2024 Turbine Blade Crisis Updates page — the name alone is a telling indicator — all installation and operation of turbine blades for the Vineyard Wind project are on hold, though placement of towers and nacelles (the equipment-bearing structures topping each tower) is permitted.

For Vineyard Wind, then, and perhaps for the Dogger Bank project as well, paper savings from going large have become a cruel joke, at least for the time being. Putting that aside, I’ve calculated the theoretical carbon price that would raise the sale price of wind electricity by the same amount that a halving of turbine capacity raised its all-in cost. Rephrased as a question: How big of a carbon price would have to be baked into the cost of prevailing fossil-fuel electricity — assumed to be from the mainstay of the U.S. power system, a combined-cycle power plant burning methane gas — to compensate for sticking with prior 6-7 MW sized offshore wind turbines and, thus, foregoing the assumed 25 percent per-kWh cost reduction from doubling turbine sizes to 13 megawatts?

For Vineyard Wind, then, and perhaps for the Dogger Bank project as well, paper savings from going large have become a cruel joke, at least for the time being. Putting that aside, I’ve calculated the theoretical carbon price that would raise the sale price of wind electricity by the same amount that a halving of turbine capacity raised its all-in cost. Rephrased as a question: How big of a carbon price would have to be baked into the cost of prevailing fossil-fuel electricity — assumed to be from the mainstay of the U.S. power system, a combined-cycle power plant burning methane gas — to compensate for sticking with prior 6-7 MW sized offshore wind turbines and, thus, foregoing the assumed 25 percent per-kWh cost reduction from doubling turbine sizes to 13 megawatts?

The answer is displayed in the text box at right: $72 per ton of CO2 (equivalently, $80 per metric ton, or tonne; these figures decrease somewhat if we factor in separate methane fees such as the levy enacted as part of the Biden Inflation Reduction Act).

In other words, a $72/ton CO2 price would have given the offshore windpower industry the same profitability enhancement it thought it would reap from doubling its wind turbine megawatt capacities . . . but without the heavy blow rendered by the multiple Haliade-X blade failures.

Granted, there’s no actual link between instituting robust carbon-emissions pricing and easing up on the impulse to push technological advances faster and faster. Even with a $72/ton carbon price, offshore wind turbines would still be in a size race.

The point, rather, is to illustrate the economic power of carbon pricing. If a $72/ton carbon price could raise wind farm profitability by the same degree as a huge and perhaps premature push into bigger frontiers, imagine the leverage that robust carbon pricing could exert on every sphere of economic and physical activity.

‘Hochul Murder Mystery’ Highlights Carbon-Pricing Hurdles

This post, a teeth-clenched corrective to my late-April Diary of a Transit Miracle, was necessitated by Kathy Hochul’s jaw-dropping “indefinite pause” (read: cancellation) of the congestion pricing program she had supported since stepping into the governorship of New York State in August 2021. Like “Diary,” it first appeared in The Washington Spectator, which posted it on June 11 as Hochul Murder Mystery.

That title placed the spotlight on Hochul, whose decision it was to abandon New York City’s congestion pricing plan; on murder, because her delay jeopardizes the precariously perched program to charge drivers to the congested (and transit-rich) heart of the NY metro area a mere fraction of the added travel delays their trips impose; and on mystery, owing to the bizarreness of her abrupt turnabout.

Six days on, however, there’s a growing sense that Hochul simply panicked . . . that her belief in (and grasp of the rationale for) imposing a robust fee on private car trips to the Manhattan central business district was too slender to withstand the criticism from motorists for bringing congestion pricing to fruition.

What’s also growing, though, is the pushback to Hochul’s peremptory, unilateral decision. Not just “the usual suspects” — transit proponents, policy wonks and urbanists — but also business interests, infrastructure contractors and good-government advocates — are mounting a sustained counterattack intended to restore the congestion pricing timeline (it had been on track to “go live” on Sunday, June 30). While that outcome may be out of reach, the final chapter in New York’s congestion pricing saga has not necessarily been written.

Nevertheless, Hochul’s pullback underscores just how hard it remains to bring about meaningful externality pricing in the United States. The high hopes we at Carbon Tax Center had invested in NYC congestion pricing as a pacesetter require that we be candid: the setback to carbon pricing, should it stand, will be considerable.

— C.K., June 17, 2024

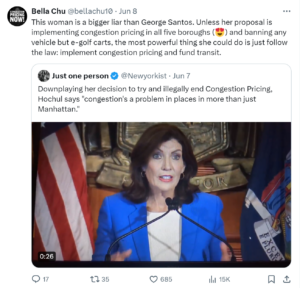

Note: Other than the photo montage, which we have reproduced from The Spectator, graphic elements here are new.

Photo montage: Riders Alliance

Not two months ago, in a brief history of how congestion pricing triumphed in New York, I canonized New York Governor Kathy Hochul, placing her alongside transportation legends Bill Vickrey (Nobel-winning traffic theorist), Ted Kheel (transit-finance savant), and the upstart Riders Alliance that in 2019 achieved what previous campaigners could not: legislation mandating a revolutionary new toll system that would weed out enough car trips to Manhattan’s core to cut down on endemic gridlock while generating revenue to enable generational expansions of subway and bus infrastructure.

Diary of a Transit Miracle, the Spectator titled that piece. Hochul, I wrote, had proved herself “a resolute and enthusiastic” congestion pricing backer. “Her spirited support,” I said, “became the decisive ingredient in shepherding congestion pricing to safety.”

Twelve days after announcing her rescission of congestion pricing, Hochul is still being ferociously “dragged” on social media. Another tweet noted that “Hochul’s decision to blow a $15 billion hole in the MTA’s budget [means] she will get blamed for every single mass transit problem going forward in a city where the majority of people take public transit.”

The story, though infuriating to urbanists, climate advocates and foes of big-city car-dominance who for decades had looked to New York congestion pricing for deliverance, is also juicy. It’s hard to recall a public policy story with as many tentacles as this one.

Let us count the ways.

Hochul’s late-in-the-day reversal obviously is a New York story. With congestion pricing, the nation’s largest city, possessor of a singular global brand, was poised to recapture its pre-eminence in progressive, bold innovation. Instead, its literal engine ― its subway system ― has been jilted at the altar.

It’s also a dystopian governance story, as befits the unilateral monkey-wrenching of a policy forged by thousands of individuals, agencies and organizations over years and, for some, decades. As livable-streets journalist Aaron Naparstek wrote on Twitter, Hochul and her Congressional consiglieres “aren’t just undermining congestion pricing, they’re discrediting the Democratic Party and they’re undermining faith in government and democracy.” New York Times editorial writer Mara Gay lamented that “Americans didn’t need a reason to feel more cynical about politics. But Gov. Kathy Hochul of New York has delivered one.”

And of course, it’s a traffic and transit story. How will New York City solve or at least mitigate its habitual, maddening gridlock, which, notwithstanding post-pandemic office malaise, was revealed last week by city transportation officials to have grown even more strangulating than it was in 2019.

Answer: it won’t. Without congestion pricing’s stiff but fair $15 toll to drive into Manhattan south of 60th Street during most hours, alternative measures to reduce New York’s staggeringly costly traffic gridlock will invariably succumb to the dreaded “rebound effect.”

Sign at June 12 rally across from Hochul’s midtown office. An estimated 800 New Yorkers marched for congestion pricing, chanting “Safer streets, cleaner air, Governor Hochul doesn’t care.” Photo by author.

And how will Hochul and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority she commands come up with a billion-dollar-a-year revenue stream to cover the interest on $15 billion in long-awaited investments in subway station elevators, digital train signals, and clean, electric buses?

Answer: they likely won’t. In a chessboard win for congestion pricing proponents, legislative leaders last week refused to rubber-stamp Hochul’s wished-for hike in the Payroll Mobility Tax, leaving her with no means to fund the new transit improvements, and putting at risk thousands of jobs in upstate factories as well as downstate. With congestion pricing the only apparent way to pay for these investments, the resistance stays alive.

Did I say resistance? The widespread pushback to the governor constitutes yet another tentacle to the story. If Hochul thought that protests over her surprise cancellation would peter out, she was badly mistaken. What began as public astonishment quickly turned to upset and grew to outrage, not just for its transit and traffic consequences but for its sheer stupidity (per climate-conscience Bill McKibben) and cowardice and cravenness (per congestion pricing campaigner Alex Matthiessen).

Nor is the rage confined to transit wonks and bike advocates. It is being expressed by the transit construction and engineering companies; by business leaders and real estate interests; by the Daily News’ editorial board as well as the Times’; by the unquenchable Families for Safe Streets who since 2018 have put their bodies on the line to spare future bereaved mothers; by urbanists who hoped other cities would follow in New York’s footsteps; and by “supply side progressives” desperate for America to actually address urban and suburban gridlock as well as housing and climate.

The fury at the governor shows no signs of abating. Midway through writing this article I attended a Riders Alliance protest in East New York where Hochul was derided as Congestion Kathy and Governor Gridlock and her face photoshopped on a faux Daily News headline, “Hochul to City: Drop Dead. Gov. Betrays Millions of Riders.” Every hour, it seems, brings word of a new demonstration, another rally, another elected official and civic leader resolving to harass and if need be break Kathy Hochul to put congestion pricing back on track.

Hochul’s action is also a car culture story. Though the city’s car-besieged and transit-rich Manhattan core is perfectly suited for congestion pricing, New York remains part of the United States and thus under the sway of mercenary auto and oil interests. Many of the city’s long-immiserated straphangers, moreover, aspire to car ownership and bristle over tolls they might someday pay, even though few working-class residents of Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island or the Bronx routinely motor to the congestion zone. Perhaps that is why the subway improvements that the tolls would pay for have yet to resonate with most “everyday” New Yorkers.

The distemper over the governor’s last-minute cancellation isn’t subsiding.

As well, New York’s political class is subway-avoidant and car-besotted, making them kissing cousins to suburban interests whose car windshields render them immune to transit’s value, except perhaps to keep others from clogging “their” road space. That the political ramifications eluded Gov. Hochul only adds spice to the story. That Manhattan and New York City as a whole couldn’t, last week, defy America’s “dominant car culture,” as the Times wrote in its Saturday editorial, is yet another sad aspect of the story.

We come now to the biggest and most puzzling piece of the Hochul congestion pricing saga: Why did she do it?

Why, after uttering nary a negative word about congestion pricing in her thousand days as governor, did she fold with a mere 25 days to go? Why, after extolling congestion pricing repeatedly and evincing genuine pleasure in being its tribune, did the governor move to murder it?

The standard explanation is that key national Democrats, most notably Brooklyn Congressmember and House Speaker-in-waiting Hakeem Jeffries, and perhaps senior White House officials as well, ordered Hochul to ice the June 30 launch to tamp voter defections in borderline House districts. This account is plausible if misguided, given that the four-month interval from June 30 to November 5 afforded ample time to “reset the default,” as Stockholm showed after its 2007 plunge into congestion pricing. The toll’s ostensible unpopularity would have ended up in the proverbial rearview mirror.

Yet these electoral concerns don’t fully add up. Any politician worth their salt knows not to abruptly reverse course on hot-button issues. And while altered circumstances can justify altered policies, no substantive change suddenly roiled New York’s transportation patterns, transit needs or economic vulnerabilities. Indeed, the governor’s fumbling attempts at justification have convinced no one.

Perhaps Hochul, an upstater and baby-boomer, was too ensnared in car culture to believe her own congestion pricing rhetoric. Perhaps campaign cash from automobile dealers moved her needle. Maybe she panicked and lost the words to tell Jeffries that helping him would destroy her political viability, end of conversation.

NYC Comptroller Brad Lander, a staunch supporter of congestion pricing, at a June 12 rally opposite City Hall, announcing litigation to invalidate Hochul’s tolling cancellation. Photo: Dave Colon, Streetsblog NYC.

Whatever caused Hochul to abandon congestion pricing, her blunder is of spectacular proportions, or so it appears to this city dweller. The prospective upset to drivers ― and not all drivers, insofar as some regarded the tolls as a means to speed their commutes ― seems almost quaint next to the actual rage of toll proponents and the derision from much of the public.

The governor can still right the ship. She could offer to lighten the toll burden around the edges, as I outlined last week. She could propose a June 30, 2025 referendum, an idea patterned on Stockholm, although who should be eligible to vote isn’t clear and could become its own bone of contention. She could cite the legislature’s hold on alternative transit funding and admit that Plan A was right all along.

The key word is admit. Not only is congestion pricing made for New York, its prolonged gestation has built it into expectations for transit finance, traffic management and the health of the city that cannot be easily unraveled.

Whatever precipitated Gov. Hochul’s loss of nerve, and whatever the consequences for her governorship and her remaining time in politics, she must reinstate congestion pricing. The need is too great, and the story too scandalous, to pretend that congestion pricing will go gentle into its good night.

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- 18

- Next Page »