"Humankind’s failure to pay for damaging the environment is the "biggest market failure ever seen," declared Sir Nicholas Stern, the author of last year’s groundbreaking report on climate change and former adviser to Tony Blair.

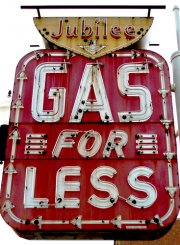

Sir Nicholas called for higher taxes on fuel to combat environmental damage yesterday at a summit of business and political leaders in Davos, Switzerland.

As reported by The Guardian (U.K.), the issue of global climate change dominated the agenda of the first day of the

World Economic Forum’s annual meeting.

Making the environment pay is one of 17 sessions focusing on climate

change this week. According to The Guardian, a majority of attendees at a standing room-only

session yesterday backed Sir Nicholas’s contention that carbon taxes

were a force for good and twice as many of the high-level attendees

said environmental protection should be a priority for world leaders as

did a year ago.

Back in the day, I was a member of Amory’s worldwide web of energy analysts who fed him our cutting-edge research (mine concerned cost escalation in the building and operating of U.S. nuclear reactors) and benefited in turn from his incisive editing and brilliant framing of our work. Along the way, however,

Back in the day, I was a member of Amory’s worldwide web of energy analysts who fed him our cutting-edge research (mine concerned cost escalation in the building and operating of U.S. nuclear reactors) and benefited in turn from his incisive editing and brilliant framing of our work. Along the way, however,