A pair of exposes in Bloomberg Green in late 2020 and 2021 revealing the sale of “meaningless carbon credits to corporate clients [by] the Nature Conservancy” highlight the fragility of offsets as a carbon-reducing policy. Click here to be directed to our discussion of the Bloomberg story, which appears at the bottom of this (long) page.

A May 2022 NYT Climate story provides a solid overview of carbon offsets’ seductive but mostly false promise, though it has its own clunker. Click here to go straight to our synopsis.

In theory, carbon offsets facilitate low-cost emissions reductions. In practice, they’ve done anything but.

Carbon “offsets,” a feature of most cap-and-trade systems, build on the uncontroversial idea of minimizing the cost to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Offsets give CO2 emitters facing carbon caps a cost-minimizing choice: they can reduce their own (domestic) emissions through the usual means: investing in or incentivizing energy efficiency and use of lower-carbon fuels; or they can buy carbon offsets that pay for actions elsewhere — typically in less-developed countries — that reduce or avoid emissions, supposedly achieving the same net reduction.

Ideally, carbon offsets finance low-carbon energy projects (e.g., wind farms and solar arrays) or projects to reduce emissions from deforestation. Reflecting this duality, the United Nations Environment Programme administers two offset programs: the “Clean Development Mechanism” (CDM) and the “Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation” (REDD) program.

The European Union’s Emissions Trading System, the world’s largest cap-and-trade system, covering about 45% of greenhouse gas emissions from 31 countries, utilizes both CDM and REDD offsets. Similarly, California’s AB-32 carbon cap-and-trade program, which started in 2013, includes offsets from five categories: U.S. Forest Projects, Livestock Projects, Ozone Depleting Substances Projects, Urban Forest Projects and Mine Methane Capture. Emitters can use offsets to meet up to 8% of their compliance obligations, but since California’s cap declines 2% per year, offsets could represent a large fraction of total emissions reductions under the cap for some time.

Why, and how, offsets have proven hard to evaluate and easy to game.

Offsets were a major feature of the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill that passed the House in 2009, and parallel Senate proposals in 2010. They were packaged into those bills as “cost control” measures to moderate the rise in energy price from steadily tightening the cap on CO2 emission permits. Offsets appealed to both polluters and potential recipients of offset funding, in effect providing political “grease” to smooth passage. But in 2008, a year before Waxman-Markey came to a vote, close analysis suggested that many intended offset projects wouldn’t actually result in emissions reductions. This raised concerns that a large supply of unverifiable offsets would undermine the emissions certainty claimed for cap-and-trade.

Later in 2008, the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office assessed the EU’s offset program under its Emissions Trading System. GAO found that over-allocation of allowances and offsets had resulted in “a price collapse.” As a result, Phase I of the ETS had “uncertain” effects on emissions in the capped countries while funding offsets of doubtful value, though GAO did hold out hope that reforms could make the system work.

Instead, the picture grew darker. GAO’s 2011 follow-up, “Options for Addressing Challenges to Carbon Offset Quality,” reported that in 2009, 81 million tons of offset credits — an estimated 59% of the ETS’s CDM offsets for that year — went to Chinese refrigerant factories to incinerate HFC-23, a chemical byproduct of refrigerant manufacturing whose per-pound greenhouse gas potency is 11,700 times that of CO2. According to GAO, the Chinese had constructed 19 new refrigerant manufacturing plants for the sole purpose of destroying the greenhouse gas byproduct in order to receive offset credits and the associated payments. According to estimates by Stanford professor Michael Wara, whereas installing equipment to capture and destroy HFC-23 at all of the facilities covered by the CDM would have cost just $100 million, these same projects were expected to generate $4.7 billion in CDM offset credits.

In 2011, EU officials finally acted to eliminate this perverse incentive, announcing plans to stop accepting offset credit for HFC-23. The Chinese government responded by threatening to vent HFC-23 straight to the atmosphere.

Similarly, a detailed analysis of offset projects to destroy HFC-23 and SF6 (sulfur hexaflouride) in Russia and the Ukraine published in July 2015 by the Stockholm Environmental Institute concluded:

[A]ll projects abating HFC-23 and SF6 under the Kyoto Protocol’s Joint Implementation mechanism in Russia increased waste gas generation to unprecedented levels once they could generate credits from producing more waste gas. Our results suggest that perverse incentives can substantially undermine the environmental integrity of project-based mechanisms and that adequate regulatory oversight is crucial. (emphasis added)

Poor information creates vast opportunities for manipulation.

While the HFC-23 sagas seem almost comical and are probably the most costly and egregious example of abuse of offsets, they illustrate a problem common to offsets — asymmetric information. Purveyors of offset projects know a good deal more about their “products” than do far-away “buyers.” And unlike the highly leveraged mortgages that were sliced and repackaged into intangible derivatives that helped crash global financial markets in 2008, offsets start out as intangibles.

GAO and other analysts of carbon offset markets group these information deficiencies into three categories: Additionality, Measurement, and Verification. They also raise concerns about the permanence of sequestration projects like forests that can later be burned as fuel, relinquishing the climate benefits that were bought with offset credits.

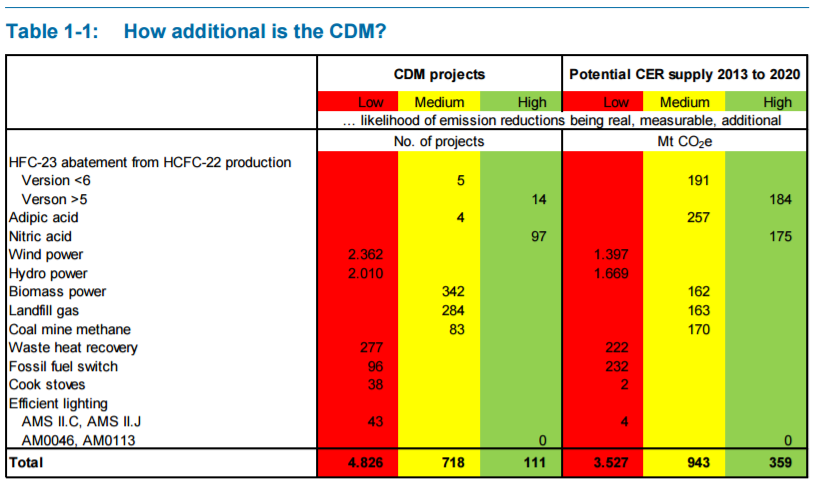

Table is from 2016 EU report noted in text directly below. CDM = Clean Development Mechanism. CER = Certified Emission Reductions.

Additionality is the issue of what would have happened if offset payments hadn’t funded the project? GAO identified many projects that got a boost from offsets, but with no clear sense as to whether they would have been built anyway without the added incentive of offset credits. Asking “What is the baseline” is inherently counterfactual, and thus untestable and unanswerable. It’s been a challenge for the UN and EU ETS to even write rules about how to review projects (which vary widely in concept, location, quality and cost), while the offset “industry” and large purveyors of offsets, particularly China, have clamored for ever more streamlined UN approvals.

A 2016 report prepared for the EU Directorate-General for Climate Action, How Additional is the Clean Development Mechanism, concluded that “the vast majority of ‘clean development’ projects [financed by carbon credits] likely fail to actually reduce emissions,” as Inside Climate News summarized in an April 2017 story. “Given the inherent shortcomings of crediting mechanisms, we recommend focusing climate mitigation efforts on forms of carbon pricing that do not rely extensively on credits,” the report said.

Measurement is the accounting problem of determining how much CO2 was avoided by this project or process or by preserving this forest. GAO found measurements of offset efficacy to be neither consistent nor transparent, even after a decade of effort by the UN.

Verification concerns the actors who check on offset projects’ completion, operation and maintenance. GAO reported that “Project developers and offset buyers may have few incentives to report information accurately or to investigate offset quality.” Everyone in the offset business — from project developers to offset sellers and buyers — wants offset values set as high as possible. GAO argues that strong, independent oversight is needed, but its report raises serious doubts about whether oversight can ever be sufficient, especially given administrative costs.

The 2011 GAO report confirmed critics’ fears that the global offset system places new hurdles in the path of energy-efficiency and other decarbonizing measures, in the form of perverse incentives under the CDM program:

[A]n offset program may create disincentives for policies that reduce emissions. For example, under an offset program that allows international projects, U.S. firms might pay for energy efficiency upgrades to coal-fired power plants in other nations. According to our previous work [GAO’s 2008 report on the EU ETS], this may create disincentives for these nations to implement their own energy efficiency standards or similar policies, since doing so would cut off the revenue stream created by the offset program.

For example, some wind and hydroelectric power projects established in China were reviewed and subsequently rejected by the CDM’s administrative board amid concerns that China intentionally lowered its wind power subsidies so that these projects would qualify for CDM funding. In addition, our review of the literature suggests that in some cases an offset program may unintentionally provide incentives for firms to maintain or increase emissions so that they may later generate offsets by decreasing them. This potential problem is illustrated by the CDM’s experience with industrial gas projects involving the waste gas HFC-23, a byproduct of refrigerant production. Because destroying HFC-23 can be worth several times the value of the refrigerant, plants may have had an incentive to increase or maintain production in order to earn offsets for destroying the resulting emissions. (emphasis added)

Acknowledging that even the best oversight and management can’t assure high offset quality, GAO suggested limiting the fraction of CO2 reductions that offsets would be permitted to provide under national cap-and-trade programs:

[T]he emissions reduction program would ensure that only a fixed percentage of the emissions permits could be affected by any problems with offset quality. All existing emissions reduction programs we reviewed use this option. In the EU ETS, regulated entities are able to use CDM credits for 12 percent of their emissions cap, on average, through 2012. In contrast, a draft Senate bill [the “American Power Act”] would have allowed a greater number of offsets into the program—approximately 42 percent of the emissions cap during the first year of the program. These percentages are based on the total emissions cap, not the required emissions reduction. As a result, such limits could mean that regulated entities could use offsets for all of their required emissions reductions, assuming a sufficient supply of offsets was available.

In other words, offsets could have overwhelmed the Waxman-Markey bill’s cap (which only declined a few percentage points each year) for decades — precisely what Prof. Wara predicted before the bill passed the House in 2009.

Proponents of AB-32, California’s cap-trade-offset program, assure us that offsets won’t overwhelm its emissions cap. Yet the intrinsic problems of offset quality will require extensive and aggressive oversight.

Conclusion

There’s no doubt that funding is needed for low-carbon energy and good forest practices in developing countries. Unfortunately, real-world experience makes offset markets a questionable funding source at best. Offsets drive down allowance prices in carbon markets, weakening incentives for decarbonization, while their uncertain quality undermines the certainty of emissions caps. A price floor, such as the $10/ton floor specified in California’s AB-32 program, can prevent a total collapse of allowance prices. Yet a simple, direct carbon tax offers an even clearer and more predictable price signals to CO2 emitters while creating far fewer opportunities for manipulation, fraud and crime.

The Nature Conservancy’s Offsets Program, Unmasked

Bloomberg Green’s Ben Elgin tore the mask off the Nature Conservancy’s offsets program with a December 2020 story documenting how the conservancy “became a dealer of meaningless carbon offsets.” Here are the opening paragraphs:

At first glance, big corporations appear to be protecting great swaths of U.S. forests in the fight against climate change.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. has paid almost $1 million to preserve forestland in eastern Pennsylvania.

Forty miles away, Walt Disney Co. has spent hundreds of thousands to keep the city of Bethlehem, Pa., from aggressively harvesting a forest that surrounds its reservoirs.

Across the state line in New York, investment giant BlackRock Inc. has paid thousands to the city of Albany to refrain from cutting trees around its reservoirs.

JPMorgan, Disney, and BlackRock tout these projects as an important mechanism for slashing their own large carbon footprints. By funding the preservation of carbon-absorbing forests, the companies say, they’re offsetting the carbon-producing impact of their global operations. But in all of those cases, the land was never threatened; the trees were already part of well-preserved forests.

Rather than dramatically change their operations — JPMorgan executives continue to jet around the globe, Disney’s cruise ships still burn oil, and BlackRock’s office buildings gobble up electricity — the corporations are working with the Nature Conservancy, the world’s largest environmental group, to employ far-fetched logic to help absolve them of their climate sins. By taking credit for saving well-protected land, these companies are reducing nowhere near the pollution that they claim.

In an April 2021 follow-up, Elgin and Bloomberg reported that the Nature Conservancy is conducting an internal review of its portfolio of carbon-offset projects, which includes more than 20 such projects on forested lands mostly in the U.S.

Visual introducing Bloomberg Green’s Dec. 2020 expose of the Nature Conservancy’s vaunted offsets program.

As both articles reported, the purchasers of offsets obtain carbon credits which they use to claim reductions in their publicly reported emissions, while the conservancy receives income from the sales. Yet the trees that are “preserved” under these arrangements are “in no danger of destruction.”

In its follow-up, Bloomberg noted that “Selling credits for well-protected trees potentially undermines the sustainability efforts of some of the world’s biggest companies. Each carbon offset is supposed to represent the reduction of one ton of planet-warming emissions that would have otherwise spewed into the atmosphere without intervention. Around the world, a wide variety of offset projects do everything from protect mangrove forests to destroy heat-trapping gases from landfills and coal mines. But offset payments channeled to already safe ecosystems don’t fundamentally change the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.” (emphasis added)

While the conservancy didn’t provide specific answers to Bloomberg’s questions, it said in a statement that it aims to meet the highest standards with its carbon projects and that its internal review will be led by scientists and a “team of experts with deep project knowledge.”

A solid though flawed look at carbon offsets by the New York Times’ climate desk

“Climate Offsets Make You Feel Good, but Do They Do Good?” was the headline of a New York Times May 18, 2022 explainer on carbon offsets. (That was the print-edition headline; the digital edition was titled “Do Airline Climate Offsets Really Work? Here’s the Good News, and the Bad.”)

The article’s subhead telegraphs its answer, “Carbon credits could eventually play an important role in fighting climate change, but right now a few dollars’ worth won’t change much.” That’s pretty much our position, though we’re somewhat less sanguine on the “eventually” part. The reasons — “additionality,” fragility and outright scams — are well summarized in the Times story. Ditto the larger problem of distraction, as Times climate reporter Maggie Astor wrote:

Part of the appeal of carbon offsets is the notion that it’s possible to meaningfully combat climate change while living our lives and structuring our society in the same way we always have. For that reason, some experts see carbon offsets as actively damaging, inasmuch as they give people cover to avoid reducing emissions at the source.

We couldn’t say it better, ourselves. Which made doubly shocking what Astor added, just two paragraphs down:

While individual activities do have environmental costs, and flying is one of the costliest, climate change is overwhelmingly driven by the actions of the fossil fuel industry.

That statement is false and unfortunate. It’s false because the main driver of climate change is demand for the energy services provided by fossil fuels — air travel, driving (these days in ever more monstrous trucks), operating supersized homes in spread-out suburbs, and so forth — and not the activities of the fossil fuel companies, whose direct emissions pale in comparison to emissions caused by using the products they manufacture and sell.

And the statement is unfortunate because it contributes to the comforting but strategically unwise choice — by now, an article of (misplaced) faith in the climate movement — to target the fossil fuel industry rather than do the hard work for carbon taxes and allied policies that go straight at the demand for fossil fuels in the first place.